Research shows that delirium, independent of age, dementia, illness severity and functional status, predicts multiple adverse outcomes for older adults, including morbidity and mortality, alongside increased length of hospital stay (Pendlebury et al, 2015; Welch et al, 2019). For the advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) evidence-based practice (EBP) is paramount to providing the best possible care outcomes for the older adult.

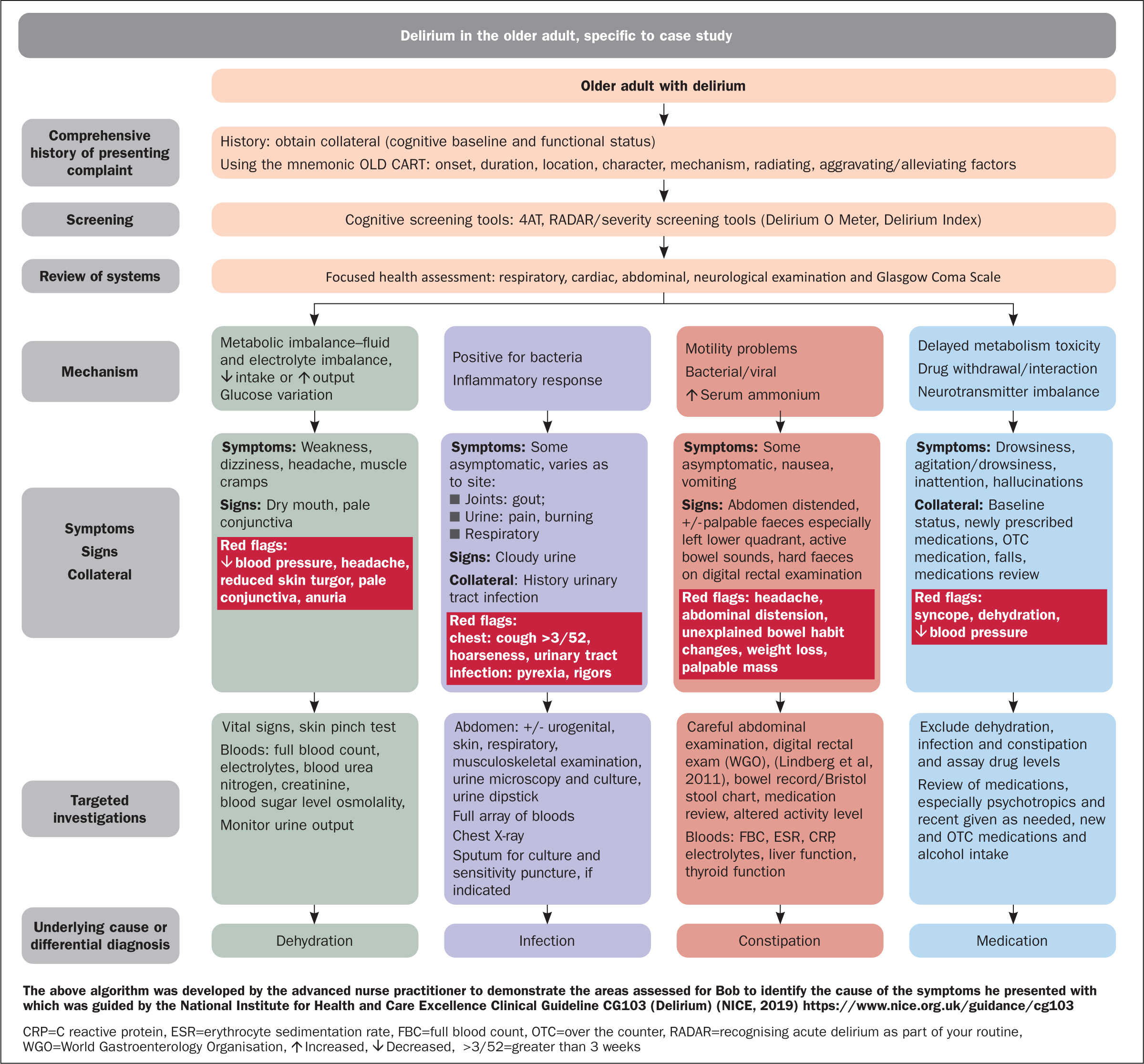

This article sets out a logical approach to obtaining a comprehensive clinical history using the most effective clinical screening tools to provide accurate diagnosis of delirium in the older adult. It presents a short case study that is followed by the application of a diagnostic algorithm, to illustrate the role of the ANP. Algorithms are typically developed from evidence-based clinical guidelines and facilitate the transfer of research to practice, providing nurses with as step-by-step approach to make effective decisions (Jablonski et al, 2011)

The context for this older adult care service is a newly established ANP role in the Republic of Ireland. The ANP older adult care service is based in community settings, where independent ANP clinics are held with direct referral from acute hospital and community primary care teams, providing early supportive discharge from acute care. The ANP also facilitates an outreach service to residential units and undertakes home visits within Health Service Executive (HSE) areas that support reduced waiting times and hospital avoidance by enabling older adults to remain at home for treatment (National Clinical Programme for Older People, 2019).

The ANP role encompasses knowledge, skills and competence to enable holistic patient assessment, along with the ability to capture, analyse and interpret patient information. These attributes are key to the assessment and diagnostic process, and demonstrate accountability and responsibility to the older adult (Nursing and Midwifery Board of Ireland (NMBI), 2017).

Background

Delirium is broadly described as a neuropsychiatric disorder of cognition, attention, consciousness or perception (Maldonado, 2018). These symptoms generally develop over a short period and can fluctuate from hours to days as a result of precipitating and predisposing factors. The condition is classified into three subtypes: hyperactive, hypoactive and mixed (Table 1). Categorisation relies on clinical presentation inclusive of psychomotor features and is associated with increased morbidity, mortality and increased length of hospital stay. Approximately 40% of older adults admitted to hospital have a diagnosis of delirium (Han et al, 2010; Ahmed et al, 2014). The differential diagnosis for delirium is broad and often multifactorial (Lorenzl et al, 2012; Maldonado, 2018). The use of an algorithm that provides a diagnostic pathway for four frequently presenting differential diagnoses of delirium in the older adult offers a systematic approach to accurate diagnosis. A case study is used to illustrate the application of an algorithm.

Table 1. Subtypes of delirium

| Hyperactive | Hypoactive | Mixed |

|---|---|---|

| Restlessness, agitation, rapid mood changes or hallucinations, and refusal to co-operate with care | Inactivity or reduced motor activity, sluggishness, abnormal drowsiness | Both hyperactive and hypoactive signs and symptoms. The person may quickly switch back and forth between the two states |

Source: van Velthuijsen, et al, 2018

Case study

Bob (not his real name), who is 84 years old, resides in a long-term care (LTC) residential facility. He is a bachelor and had worked as a builder on construction sites. Before moving into LTC, he lived alone and has a long history of smoking, alcohol excess and poor diet, resulting in raised cholesterol and subsequent atherosclerosis. His speech is clear, and he communicates appropriately in short, clear sentences with limited distraction such as environment and noise. He has many siblings who visit regularly and provide him with a good support network. His past medical and surgical history includes left carotid endarterectomy and dementia of Lewy body type, with associated cognitive deficits.

Bob had no diagnosed respiratory condition; however, on occasion he became breathless. When this occurred, he received oxygen therapy via nasal prongs which is documented in his advanced care plan (Aasmul et al, 2018). Studies (Wang et al, 2015; Armstrong and Weintraub, 2016) suggest that individuals with Lewy body dementia who are on antipsychotic medications can have adverse reactions; subsequent prescribing should be progressed with caution following careful consideration, including the risk benefit ratio. In Bob's case his previous presenting symptoms required prescription of quetiapine at low doses. While research in this area remains clinically debated, quetiapine has been shown to have the least adverse effects and is therefore the safest medication to use with this dementia type (Fox et al, 2019; Hershey et al, 2019). Bob's prescribed medications prior to and following his hospital assessment and treatment decision are listed in Table 2. This information was used to assist in building up the clinical picture and provide indicators for potential causes of delirium.

Table 2. Patient medication

| Regular medications before and after hospital admission | PRN (as needed) medications |

|---|---|

|

|

His comorbidities included type 2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, constipation and gout. More recently, Bob had been diagnosed with a 6.3 cm non-ruptured infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm located in the maximal axial diameter of the aorta. Following this diagnosis, Bob and his family met with the medical team and a decision was made to proceed with non-interventional treatment. Bob was transferred back to the residential setting and commenced on oral paracetamol 1 g three times a day, with a further 1 g dose as needed to alleviate his-left flank discomfort.

Three weeks later, Bob presented with confusion, limited attention span and disorganised thinking. On observation, he was restless and pacing the unit; staff reported that he was not sleeping well. On further assessment, Bob's vital signs were recorded as: blood pressure 140/80 mmHg; heart rate 98 beats per minute; respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, temperature 37.6°C, oxygen saturation 97% in room air. His pain score was 17/30, category 4, according to the Carey (2018) pain tool, which was developed in Ireland for the residential setting; it incorporates behaviours and numeric values, including self-report. In Bob's case, only behaviour observation was recorded: the score of 17/30 indicated severe pain and required intramuscular tramadol 100 mg for relief. Full blood tests requested including full blood count (FBC), renal, liver and bone profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), vitamin B12 and folate levels, blood glucose, arterial blood gases and a chest X-ray, which were undertaken in the residential facility. A head-to-toe physical examination raised a range of red flags including acute pain, distended abdomen with guarding of the left flank, pale bilateral conjunctive and mucous membranes, headache, reduced skin turgor, restlessness and an altered sleep-wake cycle. Bob had one episode of syncope and a drop in blood pressure caused by dehydration.

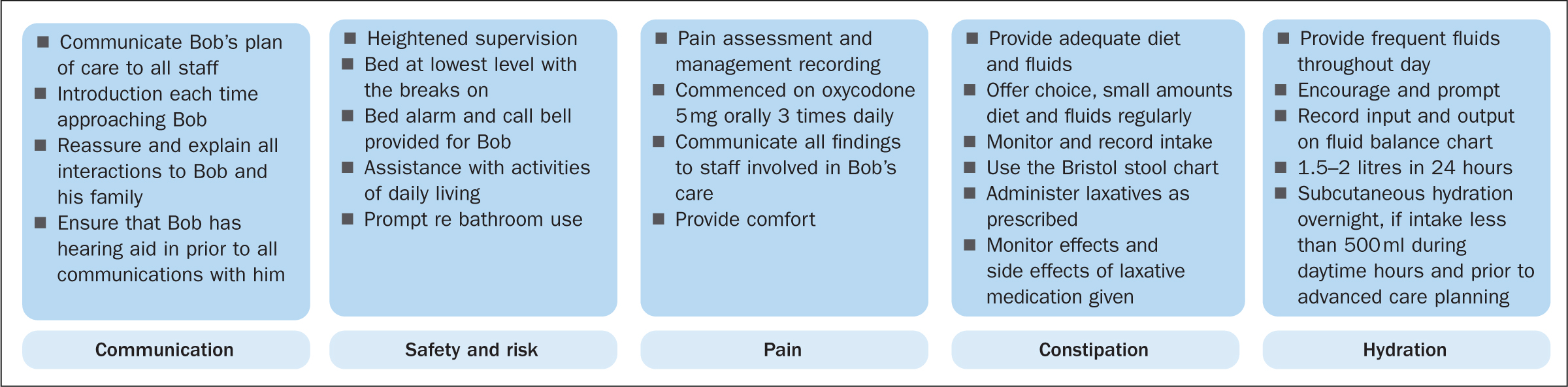

Differential diagnosis is essential to assist the practitioner in formulating an accurate diagnosis. Diseases often present with similar symptoms, so the practitioner will apply clinical reasoning to narrow down the differential diagnosis (Reinoso et al, 2018; Rhoads and Murphy Jensen, 2015). The differentials in the case of the patient, Bob, are illustrated in Figure 1, along with the red flags that presented on examination by the ANP. The blood results revealed elevated serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, low sodium, low fasting blood sugar and elevated ammonia, ESR and CRP; all other results were unremarkable. Following a comprehensive assessment and full review of symptoms using an evidenced-based clinical decision-making process, the ANP diagnosed hyperactive delirium with marked behaviour changes, increased pain levels, constipation and dehydration. The areas outlined were of concern and intervention was required to manage and treat the symptoms, as shown in Figure 2.

Following his diagnosis in the acute setting Bob was prescribed oxycodone 5 mg orally three times a day by the palliative care team prior to discharge to the residential facility. The cause of the acute pain was identified as constipation, most likely related to pressure on the bowel and the abdominal aortic aneurysm. No further diagnostic testing was advised in accordance with Bob's advanced care plan. Fluid intake was set according to his typical daily intake and laxatives were required to manage constipation. Subcutaneous or intravenous fluids were not considered with reference to his advanced care plan. Bob's only wish was to have adequate pain relief. To achieve these outcomes a person-centred care approach is vital and should include alleviating possible anxiety experienced by Bob (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2019). His overall care was managed by the ANP with multidisciplinary team collaboration.

In this patient's case, his delirium was superimposing on his dementia. Prompt and accurate diagnosis was achieved, allowing for the most appropriate intervention with the least adverse effects, by avoiding lengthy cognitive and functional decline (see Figure 1). The advanced care plan was completed with Bob, which was paramount to avoid acute hospital admission and allowed for multicomponent approaches that were person-centred and provided in a familiar environment (Martinez et al, 2015). Furthermore, advanced care planning allowed Bob and his family to plan care that was consistent with his personal values and preferences (Aasmul et al. 2018). To ensure successful care planning, staff received education specific to delirium and its precipitating and predisposing factors to support early intervention and minimise the effects of future episodes if these presented (Colomer and Vries, 2016). Professional knowledge and decision-making are central to the ANP's scope of practice, underpinning assessment and diagnosis, and ensuring accountability and responsibility (NMBI 2015). The algorithm in Figure 1 sets out the decision-making process used to assess and establish the causes of Bob's delirium.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of delirium remains poorly understood, with research looking into multiple hypotheses. These include pathogenesis, degenerating brain vulnerability, brain energy metabolism and a variety of precipitating factors to identify methods of convergence (Wilson et al, 2020). This article includes discussion of the blood–brain barrier breakdown that occurs with ageing and the associated risk factors that contribute to delirium (Varatharaj and Galea, 2017). In the older adult, alterations in the blood–brain barrier make the barrier more permeable, allowing blood and substances to pass from micro-vessels to the brain, including toxins and pathogens that will affect cognitive processes. It is thought that the downregulation of synthesis, release and inactivation of neurotransmitters play a vital part in the pathophysiology of delirium in the older adult (McCaffrey and Davis, 2012). The case study illustrates the application of a diagnostic pathway for delirium with reference to Bobs' presenting symptoms.

Differential diagnosis in advanced practice

The differential diagnosis for delirium is broad and often multifactorial (Lorenzl et al, 2012; Maldonado, 2018). According to Inouye et al (2014) the term delirium describes an array of symptoms that indicate a disruption in cerebral metabolism following transient biochemical disruptions caused by many conditions. The algorithm provides a systematic approach to four differential diagnoses of delirium: dehydration, infection, constipation and medication. In the author's clinical experience, and based on evidence, these four diagnoses present most frequently in older adults.

History taking and examination skills

Advanced health assessments that include comprehensive history taking, careful physical examination and sound clinical reasoning are crucial to the diagnostic process (NMBI, 2017). These elements assist the practitioner to narrow down the differential diagnoses (Rhoads and Murphy Jenson, 2015; Reinoso et al, 2018). In Bob's case, eliciting subjective and objective data through the health history interview using open-ended questions and active listening were demonstrated. As part of this process, it is essential to develop a rapport with the patient and family members: this is fundamental to alleviating anxiety and enabling the ANP to obtain a family history, and helps ensure that the physical examination and diagnostic tests address the relevant factors.

A patient's health history includes their medical history, treatments and risk factors for delirium, and a review of systems. A thorough review of all medications is completed with a specific focus on medication known to contribute to delirium symptoms in combination with associated risk factors; these medications (Table 3) can predispose older adults to episodes of delirium (Rhoads and Murphy Jenson, 2015; Bickley and Szilagyi, 2021). The mnemonic OLD CART (onset, location, duration, characteristics, associating factors, relieving/radiating factor, treatment) is a useful tool when obtaining information about a patient's current health status, including background and presenting complaints (Bickley and Szilagyi, 2021). This tool is one of a number of available assessment instruments that use mnemonics: others include PQRST (provokes, quality, radiates, severity and time) and SOCRATES (site, onset, character, radiation, associations, time course, exacerbation/relieving factors, severity) (Bickley and Szilagyi, 2021).

Table 3. Medication categories for consideration during assessment and review that may contribute to onset of delirium

| Prescription medication | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Analgesics

|

Anti-allergy/anti-nausea

|

Central nervous system

|

Antibiotics

|

Gastrointestinal

|

Cardiovascular

|

Psychotropic

|

Miscellaneous

|

| Over-the-counter medications and complementary/alternative medications below are also considered | |||

|

|||

Source: Alagiakrishnan and Wiens, 2004

In clinical practice, the ANP assesses all risk factors associated with the onset of delirium and completes a comprehensive screening to guide diagnosis and treatment. Focused screening in relation to presenting symptoms will also be considered to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Risk factors for delirium and required investigations are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Risk factors and investigations for delirium

| Risk factors | Investigations |

|---|---|

|

|

Once a health history has been taken and a risk factor assessment made, a thorough physical examination is conducted, applying a systematic approach to obtain objective clinical information. The initial focus is on neurological assessment, followed by a focused examination relating to each differential diagnosis (Bickley and Szilagyi, 2021; NMBI, 2017). Careful examination of the cranial nerves, and the motor and sensory systems will assist in identifying comorbidities or underlying pathology. If an underlying pathology is identified, the ANP will investigate further and consider referral onward, including to the GP if psychiatric manifestations present. A vital signs review is key and may detect the presence of red flags (Bickley and Szilagyi, 2021). Identification of red flags may indicate a serious pathology and the need for further urgent investigations for underlying serious disease (Reisner and Reisner, 2017). Red flags of significance in the case of Bob's presenting symptoms are shown in red in Figure 1.

Screening tools

Screening tools are valid and reliable methods for assessing older adults presenting with delirium, enabling comprehensive assessment of the presenting symptom(s) (Iragorri and Spackman, 2018). Delirium is diagnosed from its clinical manifestations using a recognised instrument such as the 4AT (arousal, attention, Abbreviated Mental Test 4 and acute change), developed by Shenkin et al (2018). In Ireland, the RADAR (recognising acute delirium as part of your routine) is used in daily practice, along with other tools (Table 5), to assess the severity of delirium and determine the efficacy of treatments prescribed.

Table 5. Assessment tools used by advanced nurse practitioners*

| 4AT (tool of choice) | RADAR | Delirium severity tools |

|---|---|---|

Designed for rapid assessment of delirium and cognitive impairment taking approximately 2 minutes to completeExamines four areas:

|

Delirium observation tool that can be used as part of daily routine developed by Voyer et al (2016) | Delirium O Meter developed by de Jonghe et al (2003) is a 12-item tool |

RADAR (recognising acute delirium as part of your routine) examines three areas of function:

|

Delirium Index (DI) developed by McCusker et al (1998) is a seven-item scale that includes subscales | |

| ANPs practising in both residential and community settings use all the above-mentioned tools as indicated when assessing and treating older adults presenting with confusion. However, it is important to note that in various clinical settings and research studies the DSM-5 is commonly used to formalise and help standardise assessment, without the use of additional assessment tools (Wilson et al, 2020) | ||

Extensive research recommends that delirium screening and surveillance be completed daily to establish onset, ensure accurate diagnosis and the best treatment outcomes with least adverse effects. Although standard diagnosis is made using the internationally recognised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), other validated and recognised tools of choice available to the ANP to determine the effectiveness of interventions include the 4AT for diagnosis, and RADAR and Delirium O Meter (de Jonghe et al, 2005; Voyer, et al, 2016; Shenkin et al, 2018).

Tieges et al (2020) suggested that early recognition of delirium, which can be achieved effectively by applying the 4AT screening tool, avoids cognitive and functional decline. This is a four-item observational test that is simple to use and easily applied in any setting. However, although it has been shown to detect delirium in older adults, it does not allow for diagnosis of the aetiology (Tieges et al, 2020). The tools listed in Table 5 are relatively short and assist the ANP in screening and monitoring delirium, in order to guide diagnosis and treatment. Should the underlying cause of a patient's delirium not be identified following advanced assessment and analysis of the presenting symptoms, along with the use of screening tools, a list of differential diagnoses will be drawn up by the ANP (Rhoads and Murphy Jenson, 2015).

The following sections present the process of applying the decision-making pathway and the targeted investigations for each of the four differential diagnoses presented in Figure 1: dehydration, infection, constipation and medication.

Dehydration

Dehydration results from a disruption in the body's fluid balance caused by decreased intake or increased output. The resulting negative balance reduces blood volume, and consequently blood pressure lowers, leading to a decline in glomerular filtration rate and electrolyte imbalances (El-Sharkawy et al, 2014; Reisner and Reisner, 2017). According to Masento et al (2014), dehydration is a common feature presenting in older adults, with intake deficits estimated to be as high as 30%. Even a 2% deficit will present with symptoms such as significant impairment in physical, visuo-motor, psychomotor and cognitive performances. Dehydration may prove fatal if left untreated, so it is crucial to be cognisant of the risk factors in older adults, which include decreased thirst response, impaired swallow and dementia. Older adults may also present asymptomatically, so careful examination with collateral information will help the practitioner identify signs (Bickley and Szilagyi, 2021).

A concerning complication of dehydration is the development of life-threatening hypovolaemic shock. Clinical findings may include dry mouth, sunken eyes, dry cool skin, and reduced or concentrated urine. Collateral of intake and output is crucial in determining causative factors and aiding diagnosis for prompt intervention (El-Sharkawy et al, 2014; Bickley and Szilagyi, 2021). Another important issue to consider are glucose levels: delirium has been associated with low blood sugar levels, particularly in acutely unwell older adults (van Keulen et al, 2018). In Bob's case, targeted diagnostic investigations, the results of which would have warranted an alert, included blood serum osmolality of >290 mOsm/kg and a transient increase in electrolytes, FBC, paying attention to haematocrit of >0.460 ratio, blood urea nitrogen of >8.1 mmol/litre and creatinine of >84 μmol/litre. Blood analysis will determine the presence and severity of dehydration, along with other investigations. Reduced skin turgor is another diagnostic in dehydration, however, it may be difficult to assess in older adults whose skin loses elasticity with ageing.

Infection

Acute respiratory tract infection occurs due to the invasion of the respiratory system by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Common pathogens include Streptococcus pyogenes, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis. They can affect many areas of the upper respiratory tract, including the pharynx and sinus. Pathogens involved in the lower tract include the latter, along with S pneumoniae (Siegel and Weiser, 2015). According to Siegel and Weiser (2015), respiratory infections lead in the ranking of burden of disease measured by years lost through death or disability.

Joints should also be assessed when considering infection in the older adult. Many joint problems present in the older adult, but in Bob's case this was gout, which is therefore discussed in the article. Gout frequently occurs in this patient group and is a common type of inflammatory arthritis that occurs when neutrophils, mononuclear phagocytes and lymphocytes invade the synovium of joints (Dalbeth and Haskard, 2005). The condition typically presents with all features of the inflammatory process and is triggered by a diet of excess proteins, excess alcohol intake, trauma, surgery, comorbidity such as renal or cardiac disease, and subsequent treatment interventions. On examination of an older adult, the ANP will often identify clinical manifestations that include sudden onset of severe pain, swelling, warmth and redness at the local area of the joint affected (Dalbeth et al, 2016).

The mechanism of urinary tract infection (UTI) is the presence of bacteria in the body and activation of the inflammatory response when microorganisms enter the urethra (Reisner and Reisner, 2017). Older adults are more susceptible with risk factors such as impaired bladder emptying and decreased muscle contractility. Parish and Holliday (2012) estimated that Escherichia coli accounts for 90% of urinary tract infections (UTI) in older adults and up to 55% of antibiotic prescribing.

Following a diagnosis of respiratory tract infection and/or UTI, older adults can develop dehydration and constipation, and consequently require close monitoring (NICE, 2015). An older adult with a respiratory tract infection may present asymptomatically, apart from delirium, or with a productive cough and shortness of breath; with a UTI, they may present with burning, frequency or urgency of micturition. The cardinal signs of inflammation in respiratory tract infection include cough, loss or changes to sense of smell, and congestion of the throat or larynx (Alam et al, 2013; Reisner and Reisner, 2017). In UTIs, the older adult may present with pain on micturition secondary to sensory nerve ending irritation. In addition, symptoms of fever, tachycardia, confusion, hypotension and leucocytosis may be evident before localised symptoms present (NICE, 2015).

With UTI identified as the most frequent recurring infection in older adults, clinical examination may discover pyuria as increased polymononuclear cells are present with infection. Cloudy or malodorous urine may also be evident. The presence of red flags such as pyrexia, rigors or back pain may indicate underlying pyelonephritis; males may present with urinary retention (Rhoads and Murphy Jenson, 2015; Reisner and Reisner, 2017). Urine testing for culture and sensitivity will identify whether there is infection and, if present, the causative pathogen, enabling the most appropriate intervention. Blood testing to assist in confirming diagnosis include FBC with raised white cells, CRP and ESR. Blood urea nitrogen levels increase with infection, and in males there may also be a rise in prostate-specific antigen (PSA). Infection can irritate prostate cells, giving rise to PSA. According to Parish and Holliday (2012) 30% of older adults in long-term residential settings will have a recurrence of a UTI within 1 year.

Constipation

Constipation is a common gastrointestinal disorder affecting 20% of the general population and about 50% of older adults (Vazquez Roque and Bouras, 2015). It can be defined as difficulty emptying the bowel and hardened faeces (Bharucha and Lacy 2020). Older people are affected by age-related cellular dysfunction affecting plasticity, compliance, altered macroscopic structural changes and altered control of the pelvic floor. Delayed colonic transit constipation is typically seen in the older adult (Lindberg et al, 2011). The aetiology of constipation is associated with inadequate fibre in the diet, reduced physical exercise, dehydration and medications such as anticholinergics and tricyclic antidepressants. The mechanism of constipation is associated with autonomic dysfunction, which can result from physical, chemical or emotional stress.

In addition, older adults or those with pre-existing conditions have a reduction in acetylcholine and serotonin, which affects gut motility altering peristalsis (Rhoads and Murphy Jenson, 2015; Reisner and Reisner, 2017). Constipation results in hepatotoxicity and increased serum ammonia levels, which travel through the blood and cross the blood–brain barrier inducing confusion (Camilleri et al, 2000).

Characteristic symptoms of constipation include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, crampy abdominal pain or distension. However, the practitioner must remain aware that older adults with delirium may present asymptomatically (Vazquez Roque and Bouras, 2015). The clinical findings from abdominal examination may include distended abdomen, palpable faeces (predominantly of the left lower quadrant), but on examination the patient may have active bowel sounds and a digital rectal exam will identify hard faeces (Lindberg et al, 2011). Red flags for constipation alert the practitioner to possible underlying pathologies such as cancer, for example when there is unexplained weight loss, unexplained altered bowel habit, blood in stool, a palpable mass or a family history of colonic cancer. Targeted investigations include a digital rectal exam (Rao and Meduri, 2011) and use of the Bristol stool chart to record stool consistency and size.

Laboratory blood analysis will provide information such as increased white cell count and elevated inflammatory markers. Liver and thyroid function will be assessed to rule out underlying conditions that may be precipitating factors to the delirium episode. An abdominal X-ray may show faecal loading and obstruction.

Medication

Polypharmacy is commonly seen in older adults, with reduced renal flow and delayed metabolism associated with ageing. This can lead to toxicity due to medication or higher concentrations of circulating drug (Lorenzl et al, 2012). Depression is also common in the older adult and involves imbalances in the brain, most notably the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and dopamine (Martins and Fernandes, 2012). The chemical basis of delirium is seen as an excess of dopaminergic activity and a deficit of cholinergic activity), with delirium occurring as a result of medication accounting for 40% of cases presenting in the older adult (Alagiakrishnan and Wiens, 2004).

Drug withdrawal is another factor to be considered in relation to alcohol (Lucas et al, 2019), benzodiazepines (Gould et al, 2014) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as these are known to precipitate delirium in the older adult (Herron and Mitchell, 2018). Features that may present in the aetiology of delirium as a result of medication include drowsiness, agitation, fluctuating confusion, inattention, visual disturbances and hallucinations (Alagiakrishnan and Wiens, 2004). Following history taking, careful review of all medication, including over-the-counter medications, is essential for narrowing down the differential diagnosis. Review of pain medication including drug-to-drug and drug-to-disease interactions is crucial for accurate diagnosis. The review should include newly prescribed or de-prescribed medication. A focused review of medications such as psychotropics, anticholinergic and deliriants is required in this population as listed in Table 3. Anticholinergic burden is an important aspect of the medication review by the ANP when assessing for cognitive decline and delirium. These medications, along with alterations in blood–brain barrier and hormone imbalances, are known to play a role in medication-induced delirium (Inouye et al, 2014).

The ANP must be familiar with red flags such as drug interactions, drug withdrawal, falls and dehydration as possible indicators of serious disease. Targeted investigations involve excluding dehydration, infection or constipation. Laboratory blood tests will be guided by the full assessment and an assay of drug levels may be indicated.

Conclusion

This article has outlined an evidenced-based decision-making pathway used by the ANP to establish possible causes of the clinical presentation of delirium in the older adult. The disease entities of delirium are overly broad, and often multifactorial, and in general present with similar symptoms. A thorough and detailed history including collateral with accompanying focused physical assessment is therefore fundamental to ensure accurate selection of diagnostic modalities. Using a structured approach enables the ANP to narrow the differential diagnosis of delirium to dehydration, infection, constipation and medication.

The article has also discussed underlying pathological processes and diagnostic modalities. An algorithm to assist the diagnostic evaluation of the presenting symptom of delirium in an older adult has been presented and critiqued using the case study of patient Bob. This algorithm is currently used by the author to guide practice and it is anticipated that colleagues in Ireland, the UK and internationally may find the algorithm useful. Additionally, they may incorporate it as part of their evidenced-based nurse-led service, enabling optimal advanced care of the older adult presenting with delirium.

A person presenting with signs and symptoms of acute delirium requires expert care and management, regardless of their demographic background.

KEY POINTS

- The ANP working in older adult care is competent and capable to effect evidence-based change in complex care settings

- The differential diagnosis of delirium is broad and multifactorial, requiring advanced comprehensive clinical decision-making, knowledge and skills

- Evidence-based algorithms guide clinical practice and facilitate the transfer of research to practice, providing nurses with a step-by-step approach for effective decision-making

- Advanced care planning is essential to achieve person-centred care for the older adult in the care setting of their choice

CPD reflective questions

- Think about the likely causes of delirium in the older adult. How would an algorithm assist with determining the cause(s)?

- Consider how you would manage a patient once you have the underlying diagnosis? Is the patient best managed in the acute or community setting?

- Consider the clinical scenario in the article. Is it useful for you practice?

- What can you do to improve your skills in the assessment and diagnostic processes?