Surgical abdominal emergencies are relatively uncommon in the paediatric population, but may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality if they are not recognised and managed appropriately. Diagnoses of paediatric surgical conditions may be challenging because of their non-specific presentations, particularly in the early stages; many pathologies occur only at specific ages, and are seldom or never seen in adult patients. Table 1 highlights some differences in surgical presentations between children and adults.

Table 1. Differences in surgical presentations between children and adults

| Adult | Child | |

|---|---|---|

| History | Reported directly from the patient in most cases | Usually obtained from parent or guardian (sometimes from the child, if age appropriate) |

| Examination | Often straightforward. Patient generally co-operates | Examination often more difficult. Younger patients in particular may not be co-operative and distraction techniques may be necessary |

| Congenital surgical conditions | Unlikely to present in the adult population | More common, especially in the first 4 weeks of life |

| Conditions causing pain | More likely to report focal symptoms | Difficult to ascertain from the history. Focal symptoms rarer, non-specific symptoms common |

| Nature of pathology | Condition specific | Frequently age specific (see Box 1) |

Nurses are often the first to encounter unwell children during triage and initial assessment, and therefore play a pivotal role in the early recognition and escalation of unwell patients. The aim of this article is to provide an idea of how surgical abdominal conditions in children present. Two illustrative case studies are included to demonstrate how these emergencies may present in clinical practice and that a structured approach is required in managing such cases.

Epidemiology

A study conducted in Taiwan over 3 years, identified that 10% of 3980 paediatric patients who presented to the emergency department (ED) with abdominal pain had a true ‘acute abdomen’ (Tseng et al, 2008). This is defined as a sudden onset of severe abdominal pain with associated nausea or vomiting developing over a short period that needs urgent attention and treatment. It may be caused by an infection, inflammation, vascular occlusion or obstruction (Patterson et al, 2021). The study found that the cause of presentation varied depending on the age of the patient, with acute appendicitis being the most common cause in children older than 1 year (68.7% of cases), followed by traumatic injury. The commonest cause in infants was incarcerated inguinal hernia (45.1%), followed by intussusception (41.9%) (Tseng et al, 2008). A national study from the USA, based on an average of 450 000 paediatric admissions a year, highlighted that surgical conditions accounted for 12.7% of all paediatric discharges (Tzong et al, 2012).

Common surgical presentations in children

Paediatric surgical emergencies may be caused by disease, trauma or congenital malformations, and span from the neonatal period to older children, with particular conditions occurring more commonly at certain ages (Aboagye et al, 2014). Box 1 illustrates the most common causes of abdominal surgical problems in relation to age. Brain tumours can present in childhood with abdominal symptoms of nausea and vomiting (Brain Tumour Charity et al, 2021).

Box 1.Surgical conditions in children varies with age

TracheoesophageaI fistula

Neonatal conditions

|

Infants up to 1 year and pre-school age

|

Adapted from Davenport, 1996; Aboagye et al, 2014

Neonatal conditions

Advances in antenatal ultrasound screening have enabled the recognition of many congenital surgical problems in utero. Where early surgical intervention will be necessary (eg. diaphragmatic hernia, tracheoesophageal fistula), babies will usually be electively delivered in specialist surgical units. Not all such conditions are recognised antenatally, and some will present post-delivery and need transfer to specialist neonatal surgical centres. These are outlined in Table 2. In neonates who need resuscitation or stabilisation, the updated Newborn Life Support (NLS) guidance published in 2021 should be followed (tinyurl.com/newborn-resus).

Table 2. Surgical conditions in neonates

| Condition | Signs and symptoms | Initial management |

|---|---|---|

| Tracheoesophageal fistula and oesophageal atresia: an abnormal connection between the oesophagus and the trachea, or blind-ending oesophagus |

|

|

| Duodenal atresia: congenital absence or complete closure of the duodenum |

|

|

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: congenital defect in the diaphragm that allows bowel to herniate into the thoracic cavity |

|

|

| Malrotation of the gut: incomplete rotation of the midgut during development, which may lead to volvulus if left untreated* |

|

|

| Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC): inflammation of the bowel which may progress to necrosis and perforation* |

|

|

| Meconium ileus: mechanical small bowel obstruction caused by viscous meconium (may be associated with cystic fibrosis)* |

|

|

| Gastroschisis and exomphalos: abdominal wall defect resulting in the protrusion of bowel outside of the abdominal cavity |

|

|

Adapted from Fawke and Cusack, 2014; Hull et al, 2014

Surgical conditions in infants and pre-school children

The conditions seen in infants up to the age of 1 year may have a more insidious onset than those described above, but still carry the potential for sudden clinical deterioration, hence the need for timely recognition and initial stabilisation. Inguinal hernias, which occur in up to 30% of premature infants (Zamakhshary et al, 2008), may be managed on either an elective or emergency basis, depending on the clinical presentation. Intussusception is the most common time-critical abdominal emergency in early childhood, especially in patients under 2 years of age (Lloyd and Kenny, 2004). Table 3 outlines common surgical cases in children in this age range.

Table 3. Surgical conditions in infants and pre-school children

| Condition | Signs and symptoms | Investigation and initial management |

|---|---|---|

| Pyloric stenosis: abnormal narrowing at the pylorus (the passage between the stomach and first part of the small intestine) |

|

|

| Inguinal hernia: protrusion of abdominal contents through the inguinal canal and into the groin |

|

|

| Intussusception: telescoping of one segment of the bowel onto the next, leading to obstruction and subsequent bowel ischaemia |

|

|

| Biliary atresia: closure or absence of the bile ducts, preventing bile drainage and leading to progressive liver damage |

|

|

Surgical conditions in older children

Appendicitis is the commonest abdominal surgical emergency in this age group (Alder et al, 2010). Table 4 shows the surgical conditions commonly encountered in this age group. Inguinal hernia may also be encountered, and the management is described in Table 3 and Table 4. It is important to specifically ask about testicular problems, as the information is unlikely to be volunteered.

Table 4. Surgical conditions in older children

| Condition | Signs and symptoms | Initial management |

|---|---|---|

| Appendicitis: inflammation and infection of the appendix, usually secondary to blockage by mucus or faeces |

|

|

| Testicular torsion: twisting of the spermatic cord, which compromises blood flow to the testicle |

|

|

Management

The management of paediatric surgical conditions should involve a focused history and examination, appropriate investigation, medical stabilisation and definitive surgical intervention. Simultaneous resuscitation and ongoing monitoring for signs of clinical deterioration should also be carried out during assessment using the ABCDE (Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure) approach.

History

A detailed and focused history should be obtained from the child and/or parents and general questions should be asked about:

- Past medical and surgical history

- Medication history and allergies

- Immunisations

- Feeding and weight gain

- Developmental milestones

- Birth history

- Travel history

- Family history of any relevant condition eg pyloric stenosis, meconium ileus (associated with cystic fibrosis).

More focused questions will need to be asked depending on the presenting complaint, which is often abdominal pain, vomiting or ‘lumps and bumps’ in surgical cases. Table 5 highlights red flags in the history which may be identified by the nursing team during initial assessment, and should prompt early surgical review.

Table 5. Red flags in the history of presenting complaint, and conditions to consider in these cases

| Red flag symptoms | Conditions to consider |

|---|---|

|

|

Adapted from Harries et al, 2015

Any history of any abdominal trauma should be sought, as these may be of particular relevance in children involved in sporting accidents causing abdominal trauma. The possibility of non-accidental abdominal injury should always be considered. A thorough examination of systems should be taken to elucidate any associated symptoms which may not have been reported by the child or guardian in initial presentation. Some important questions to consider when dealing with surgical presentations include:

- When did the symptoms start?

- Was there any abdominal injury? (in bicycle handlebar injury bruising may not be visible)

- Has your child had any fevers?

- Have you noticed that your child dislikes nappy changes or bowel movements (moving and handling)?

- Has there been any bilious/green vomit?

- How has your child been eating and drinking? (consider reduction in appetite)

- Have you noticed that your child has become more irritable or restless?

- It may be appropriate to assess pain using the SOCRATES acronym in older children and adolescents (Swift, 2015):

- Site: ask the child to pinpoint exact point of maximal pain. Has it moved?

- Onset: sudden or gradual onset

- Character: sharp, dull, colicky

- Radiation

- Associated symptoms: fever/vomiting/change in bowel habit

- Time course: is the pain constant or does it come in waves? Is it worse at particular times of day?

- Exacerbating and relieving factors: position, relation to meals

- Severity.

Physical examination

An ABCDE approach should be taken when a child presents to the ED. A full set of basic observations should be recorded in the paediatric early warning score (PEWS) chart. This initiates an objective early discussion with the paediatric and surgical team for early assessment/intervention.

A comprehensive physical examination should be carried out by an appropriately trained health professional (such as paediatric advanced nurse practitioner, emergency nurse practitioner or a medical professional). Particular attention should be paid during examination of the oropharynx, chest, skin, external genitals and anal region. This is essential to identify the underlying cause of symptoms (Marin and Alpern, 2011). Examining a distressed child may present a challenge to the clinician, and distraction by parents or guardians, or the use of play therapists may be necessary to elicit the signs accurately.. The child's overall behaviour and appearance should be noted. The colour of vomitus should be inspected to provide an objective assessment. Bilious vomiting (green in colour) is associated with a surgical pathology unless proved otherwise. Table 5 and Box 2 list some important physical signs of acute abdominal pathology.

Box 2.Focused examination of relevant systems: red flags identified during the abdominal exam warranting urgent surgical review

- Guarding: involuntary contraction of the abdominal wall due to inflammation of internal organs

- Rebound tenderness: pain on sudden release of pressure which may indicate peritonitis (inflammation of the lining of the abdomen)

- Rovsing's sign positive: palpation of the left lower quadrant increases pain felt in the right lower quadrant (often seen in appendicitis)

- Murphy's positive: arrest of inspiration on palpation of the right upper quadrant (seen in acute cholecystitis)

- Tenderness over McBurney's point: pain on palpation of the abdomen, two thirds of the distance between the umbilicus and the anterior superior iliac spine (seen in appendicitis)

Investigation

Investigations to be carried out on the child will be guided by the initial presentation, and have been outlined in Tables 2–4. It is helpful to consider some basic investigations during the initial triage:

- Full blood count (FBC): an elevated white cell count (WCC) and raised platelet counts may suggest infection or inflammation (such as appendicitis), although a ‘normal’ value does not exclude it. Low haemoglobin levels may be seen in cases where there is bleeding such as intussusception and with abdominal trauma

- Urea and electrolytes (U&E): may be deranged in children presenting with fluid loss due to diarrhoea and vomiting associated with conditions such as appendicitis, intussusception, pyloric stenosis. May also be seen where fluid has been lost into the tissues of the ‘third space’

- C-reactive protein (CRP): may be raised in conditions presenting with inflammation or infection, eg necrotising enterocolitis, appendicitis, intussusception

- Liver function tests (LFTs): may be abnormal in a multitude of conditions, especially biliary atresia or liver trauma

- Blood group and save: should be considered before preparing a patient for surgery

- Lactate: may be raised in conditions that present with inflammation or infection, including necrotising enterocolitis, appendicitis, and intussusception, or when shock is present

- Urine dipstick: acute urinary tract infection and renal trauma

- Pregnancy tests: should be performed for post-menarchal adolescent females presenting with acute abdominal pain

- Abdominal X-ray: may be beneficial in conditions with structural problems or as an initial assessment tool in necrotising enterocolitis, duodenal atresia, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, tracheoesophageal fistula and oesophageal atresia, meconium ileus, renal calculi, and bowel obstruction or perforation

- Abdominal ultrasound scan: will be helpful in a large number of conditions and will help in the diagnostic pathways in conditions such as pyloric stenosis, intussusception, testicular torsion, inguinal hernia.

Treatment

Children who need resuscitation and stabilisation should be managed initially using an ABCDE approach. The nursing team can help by assessing children rapidly, and help support parents by providing explanation and reassurance. Initial management for each condition is outlined in Tables 2–4. A general overview for managing patients with acute surgical abdomen is discussed below.

Children in whom an acute surgical pathology is suspected should be kept nil by mouth (NBM) and administered intravenous (IV) fluids and appropriate analgesia. The nursing team can initiate the process by applying a topical anaesthetic cream while triaging the patient and inserting an IV cannula and sending some basic blood investigations, as highlighted in the section above. A nasogastric tube (NGT) should be inserted and put on free drainage if there is vomiting or abdominal distension. In some cases, fluid bolus (10-20 ml/kg of normal saline) and IV antibiotics may be required.

Specialist management of these patients extends beyond initial triage and assessment. The basics of surgical intervention needed for specific conditions are outlined in Tables 2–4, but detailed discussion is beyond the realms of this article. The nursing team plays an important role in the postoperative stage, and they will be involved in undertaking the following:

- Accurate record of fluid balance: IV fluids, NGT drainage, vomit, urine output and surgical drain output, which should be measured every 4-6 hours

- Pain control: regular paracetamol in mild pain, increased to opioid-based analgesia if pain is more severe (which may be on the ‘as required’ side of the drug chart)

- Encouragement of mobilisation: including deep breathing and gentle activity

- Monitoring of nutrition to promote recovery; may need to involve the dietitian

- Continuous recording of vital observations through PEWS scoring (or as per local policy)

- Highlighting and escalating any concerns to the paediatric and/or surgical team.

Role of the nursing team

Nurses are of vital importance to the early recognition and escalation of acute surgical presentations in children, and are also greatly involved in parental education, as well as ongoing postoperative care and management in the community. Table 6 provides an overview of the different roles of the nursing team involved in these cases.

Table 6. Role of the nursing team in managing surgical presentations in children

| Nurse | Role |

|---|---|

| School and community nurses |

|

| Practice nurse |

|

| Nurses in the emergency department |

|

| Health visitors |

|

| Children's ward nurses |

|

Adapted from Thayalan et al, 2013; Blackburn, 2015; Harries et al, 2015

Case studies

Case 1

History

A 9-month old girl was brought to ED with a 1-day history of abdominal pain. During triage, the ED nurse noticed that she pulled her legs up towards her chest, and kept them there for around 2–3 minutes. The parents reported similar episodes over the past 24 hours, with one episode of vomiting

Examination

While recording and documenting basic observations, the emergency nurse practitioner noticed red-coloured nappy contents, which she recognised as ‘redcurrant jelly stools’. The child was then managed using an ABCDE approach. Abdominal examination revealed distension and tenderness. She was hypotensive, with a blood pressure of 60/42 mmHg and a heart rate of 158/min, but remained alert. Other observations were within normal range.

What is the immediate priority intervention?

Stabilise the child, keep NBM with NGT placement, monitor input–output, administer fluid bolus and antibiotics, and consider urgent transfer to a specialist surgical centre.

Differential diagnosis

Intussusception, gastroenteritis, infantile colic, bowel obstruction, sepsis.

What are the appropriate investigations in this setting?

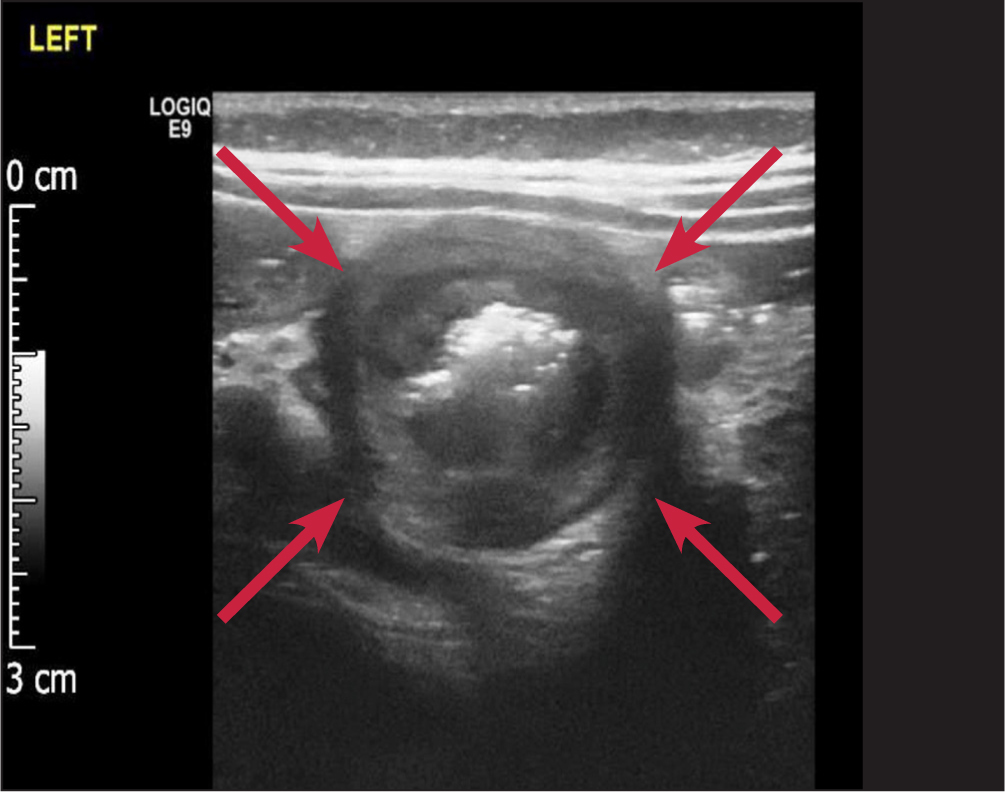

Bloods (FBC, U&E, LFTs, lactate) and abdominal X-ray, which may show a filling defect, but may be normal. An ultrasound scan will show invagination of a segment of bowel onto the adjacent segment, indicative of intussusception. This is known as the doughnut or target sign (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ultrasound scan showing intussusception, with the ‘doughnut or target’ signs clearly visible

Figure 1. Ultrasound scan showing intussusception, with the ‘doughnut or target’ signs clearly visible

What other steps would need to be considered?

Fluid resuscitation, transfer to a surgical unit for air enema reduction or open surgical intervention.

Final outcome

Ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis of intussusception, and the infant was transferred to a specialist surgical centre where air reduction was achieved. It is important to remember that intussusception may not present with the classic triad of symptoms (vomiting, abdominal pain and bloody stool, described as ‘redcurrant jelly stools’) in all cases and clinical suspicion is necessary.

Case 2

History

A 12-year-old boy presented to the GP surgery, where the practice nurse noticed that he was struggling to walk, had a crouched posture with a low-grade fever and was wary of abdominal palpation. The boy was transferred to the hospital with suspected appendicitis, after being given pain relief and being kept NBM.

Examination

The advanced paediatric nurse practitioners noted that the child was pale and recorded a temperature of 37.9°C. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in the right iliac fossa, over McBurney's point, and the boy had rebound tenderness. His chest was clear and heart sounds were normal.

What is the immediate priority intervention?

Urgent surgical assessment, keep the child NBM and give intravenous fluids and analgesia.

Differential diagnosis

Appendicitis, mesenteric adenitis, gastroenteritis.

What are the appropriate investigations in this setting?

Blood tests (which may show elevated WCC/CRP due to an ongoing inflammatory process), urinalysis, ultrasound scan, and CT imaging may be requested if there is a suspicion of perforation, abscess formation, or the diagnosis is unclear.

What other steps would need to be considered?

Time-critical surgical intervention, postoperative fluid management, with a fluid balance chart.

Final outcome

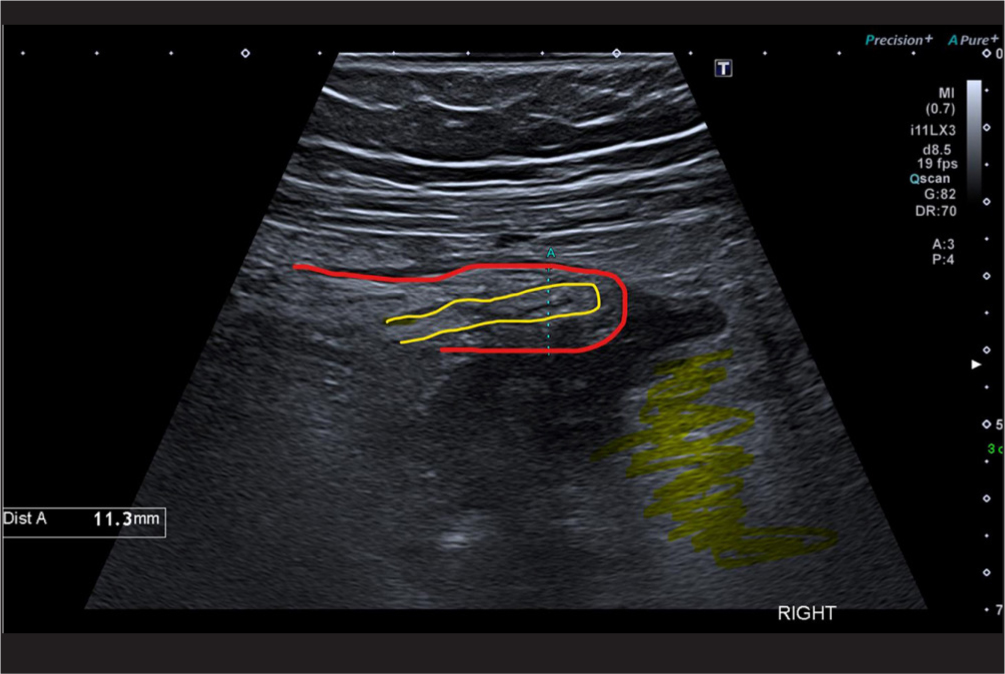

The boy was reviewed by the paediatric team, and clinically diagnosed with appendicitis. He had elevated CRP of 126 mg/L (normal <10 mg/L). Ultrasound scan revealed a thickened, blind-ended structure, consistent with an inflamed appendix and free fluid surrounding this structure, with the right lower abdomen and appearance consistent with acute appendicitis (Figure 2). An emergency appendectomy was performed by the local surgical team.. The boy remained in hospital for a few days, after which he made a full recovery and was discharged home.

Figure 2. Ultrasound scan showing a ‘classic’ longitudinal image of acute appendicitis. The appendix is outlined in red, lumen in yellow and some shading in the surrounding hyperechoic fat, which is a sign of inflammation

Figure 2. Ultrasound scan showing a ‘classic’ longitudinal image of acute appendicitis. The appendix is outlined in red, lumen in yellow and some shading in the surrounding hyperechoic fat, which is a sign of inflammation

Conclusion

Surgical abdominal conditions in children have a wide range of clinical presentations, and health professionals should be aware of, and alerted to, red flags in the history and examination. In any sick child where there is clinical suspicion for such pathology, urgent paediatric surgical review should be sought. It is important to have continuous communication both within the team and with the child and parents/guardian. Most surgical conditions benefit from time-critical intervention and transfer to specialist centres, to improve clinical outcomes and deliver the best possible care.

LEARNING POINTS

- Acute abdominal surgical disorders are uncommon in childhood, but need timely recognition, diagnosis and management

- The causes of these disorders are largely dependent on age

- Bilious vomiting at any age requires urgent medical attention

- First-line management should always use the ABCDE approach for assessment

CPD reflective questions

- Nurses are suitably placed to identify and manage surgical conditions. Based on your previous experience, consider a few challenging scenarios you may have come across and how these were managed

- Reflecting on the case studies in the article, can you identify three or four scenarios of abdominal surgical conditions in children where nurses working in different clinical settings have made a difference, either by recognising the condition early or by identifying deterioration in clinical status through regular observations, or clinical assessment, and escalating concerns to senior health professionals?

- Consider some strategies for future management that nurses can discuss with families while discharging children who presented with a surgical condition and how they would be able to identify deterioration at home