A child who presents with decreased level of consciousness (dLOC) may cause great concern to the clinical team involved. The list of potential causes is long and features a wide range of pathologies, many of which are rare but can have severe outcomes if not diagnosed correctly and treated in a time-critical manner. Nurses frequently meet these children at initial presentation, and therefore play a vital role in the care of such patients. The aim of this article is to provide a logical and practical guide to the identification and initial management of the varying differential diagnosis in a child presenting with dLOC. Two illustrative case studies are also included to highlight how these cases may present and show how health professionals have made a difference in the overall management of these children.

Identifying decreased level of consciousness

Consciousness can refer to either the state of wakefulness, awareness, or alertness in which most humans function while not asleep. Decreased consciousness is considered to be present when there is a deficiency in wakefulness, awareness and/or alertness. It is therefore crucial for health professionals to be aware of a child's normal behaviour and level of consciousness and they may need to verify this with the parents if there is doubt (Jellinger, 2009).

Children with dLOC may be confused, lethargic, obtunded (showing slowed responses to stimuli), stuporose (dazed, with dulled sensibilities and near-unconsciousness), comatose, or irritable (Avner, 2006; Song and Wang, 2017). The commonality associated with these presentations is that the patient is showing signs of impairment of the higher cognitive functions of the brain.

A number of scoring systems have been developed in an attempt to quantify and objectify the degree of altered consciousness. The simplest of these is the AVPU scale that relates the response of a patient to stimuli of varying intensity; it includes normal alertness (A), response to voice (V), response to pain (P) and unresponsive (U) (Hoffmann et al, 2016). The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and modified Paediatric GCS are more complex scales originally designed for use in head injury. These scales include assessing patients' eye opening, vocal and motor response, and have a maximum score of 15 and a minimum of 3; a score of 14 or less indicates a dLOC. The AVPU scale has been shown to have good correlation with the Paediatric GCS scale, which requires more skill to apply and is also more time consuming (Hoffmann et al, 2016).

A presentation of dLOC in a child should be considered an acute medical emergency, this is because it can result in an inability of a child to protect their own airway, and even result in problems in maintaining a patent airway. If the primary insult to the brain is left untreated, it can lead to severe morbidity or even death. Rapid and logical approaches to evaluation and treatment are therefore required when a patient presents with dLOC. Recent guidelines offer expert advice on how to manage these patients and help with diagnoses that do not depend on the clinical team's level of clinical experience (Bowker et al, 2006; Chan et al, 2013; Reynolds et al, 2018).

Epidemiology

Decreased consciousness occurs more frequently in younger children, and infection is the single most common aetiology. This was shown in a study of the incidence and outcome of non-traumatic coma in children aged between 1 month and 16 years, who were admitted into hospital or had a community death associated with non-traumatic coma in a prospective UK-based epidemiological study conducted over a 16-month period (Wong et al, 2001). In this study coma was defined as GCS score 12 or lower. The overall incidence of non-traumatic coma in children (under 16 years old) was 30.8 per 100 000 per year; the highest incidence of dLOC according to age was 160 per 100 000 in children under 1 year old; for children aged 2-16 years the incidence in each age group was less than 45 per 100 000. The study also explored the aetiology of dLOC in these patients. The most common cause of presentation was infection (38% of cases) of which 47% was due to Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) infection. Herpes simplex encephalitis was very rare and accounted for less than 1% of cases. Central nervous system specific aetiology became more common with increasing age (Wong et al, 2001). However, it may be noted that with the availability of increasing numbers of vaccines, including the meningococcal B and C vaccines, incidence of dLOC due to infections in the UK should decrease and other causes, as mentioned in Table 1, need to be explored.

| Condition | Presentation |

|---|---|

| Shock | Altered consciousness, and any one of the following: cold peripheries, capillary refill >2 seconds, poor pulses, decreased urine output (<1 ml/kg/hour), low blood pressure Child/infant can also be hard to rouse, or off feeds |

| Sepsis | Altered consciousness and two or more of the following: temperature >38°C or <36°C, tachycardia, tachypnoea, white cell count >12 or <4, or a non-blanching purpuric rash |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | Need to have all three of: |

| Hypoglycaemia | Capillary or laboratory glucose <2.6 mmol/litre |

| Hyperammonaemia | Recognised if plasma ammonia is >200 micromol/litre |

| Raised intracranial pressure | Papilloedema or 2 or more of the following: GCS <8 or U on AVPU, abnormal breathing patterns, abnormal pupils, abnormal posture and abnormal caloric response |

| Hypertension | Systolic BP >95th centile for age on 2 separate readings (with an appropriate-sized cuff) |

| Prolonged convulsion | Convulsion lasting longer than 10 minutes |

| Post-convulsive state | Normal capillary glucose and dLOC persisting >1 hour after convulsion |

| Meningitis | Infants < 12 months: non-specific symptoms such as fever, seizures and shock, rash, bulging fontanelle, abnormal posturing, irritability |

| Encephalitis | Focal neurological signs, fluctuating consciousness. Features of viral illness. Contact with herpetic lesions or no obvious alternative cause could be at risk of encephalitis—herpes simplex viral encephalitis is rare, most cases are due to other viruses, but it is a diagnosis not to be missed given associated morbidity, mortality, and potential to treat the condition. History of travel to tropical regions |

| Febrile seizures | Fever with seizures. Often associated with features of mild viral infections of upper respiratory tract, much more rarely seen with bacterial infections |

| Trauma/other | Any evidence of trauma, eg from a collapse or non-accidental injury (NAI). In NAI do not expect an accurate or complete history. History of drug abuse. Access to prescribed or recreational drugs |

| Cause unknown | No clues as to the cause following history, examination and core investigations |

Source: adapted from Bowker et al, 2006; Chan et al, 2013; Reynolds et al, 2018

Studies across the globe have also shown infection to be an important cause of dLOC. Out of 115 children admitted with dLOC in a study based in Malaysia, 80 (69%) were found to have an infective aetiology (Sofiah and Hussain, 1997). A study conducted in Nigeria reported infection as the cause in 85% of children who suffered from non-traumatic coma (Ibekwe et al, 2011). A study from India found the aetiology of non-traumatic coma in children to be due to infection in 58% of cases (Suganthi et al, 2016). Key points that can be drawn from these studies include the importance of thinking about infective causes, including sepsis, in children with altered consciousness; infants and younger children being at particular risk. It is important to note, however, that infective causes of dLOC in the studies above will likely vary from those causing dLOC in the UK population. For example, cerebral malaria will be a far more common cause of dLOC in the tropical and subtropical regions of the globe, in comparison with the UK.

Furthermore, although relatively rare, it is also vital to be aware of non-accidental injury to children, particularly for repeat attenders to hospital with unusual histories and signs of other physical injury such as bruising, but also bearing in mind that obvious signs of injury may be absent in some cases. More than 40% of deaths from child abuse occur in children under 12 months old, with abusive head injury being the most common cause of death and disability. These children may present with non-specific symptoms, therefore up to 30% of children with abusive head injury may be misdiagnosed initially (Jenny et al, 1999; Sheets et al, 2013).

Pathophysiology

The cerebral cortex and the reticular activating system (RAS) play an important role in the regulation of consciousness and conscious awareness. The RAS lies within the brainstem/midbrain, controlling respiration and cardiovascular functions. This causes activation of the cerebral cortex, the part of the brain where actions are conceived and initiated (Crossman and Neary, 2010).

In basic terms the pathophysiology of dLOC is the result of depression of both cerebral cortices or localised abnormalities of the ascending RAS (aRAS). The aRAS is a neural circuit situated in the midbrain, pons and medulla; its function is to receive sensory input and to modulate wakefulness and alertness, and therefore it has an effect on the state of consciousness. Altered states of consciousness can be the result of focal lesion in areas affecting the aRAS and directly within the aRAS, including pressure (such as from cerebral oedema in diabetic ketoacidosis) and stroke (Zeman, 2005). In addition to the diffuse dysfunction of the cerebral hemisphere secondary to inadequate blood supply, inadequate substrates (oxygen or glucose required for normal metabolism), trauma, infection, toxins or metabolites may also result in altered levels of consciousness, as can abnormalities of the central nervous system such as meningitis or encephalitis (Jellinger, 2009).

Differential diagnosis and clinical presentation

Because dLOC is a non-specific finding with a wide range of potential differential diagnoses, it is crucial to obtain a thorough but focused history along with a comprehensive physical examination. The aetiology of dLOC can be refined into a simple mnemonic, encompassing in broad terms most of the potential causes, which can help organise thoughts when seeing such patients.

Song and Wang (2017) referred to the MOVESTUPID mnemonic, which stands for:

Table 1 discusses some of the key differential diagnoses for dLOC in children, along with a brief description of the key aspects of their clinical presentation.

Management

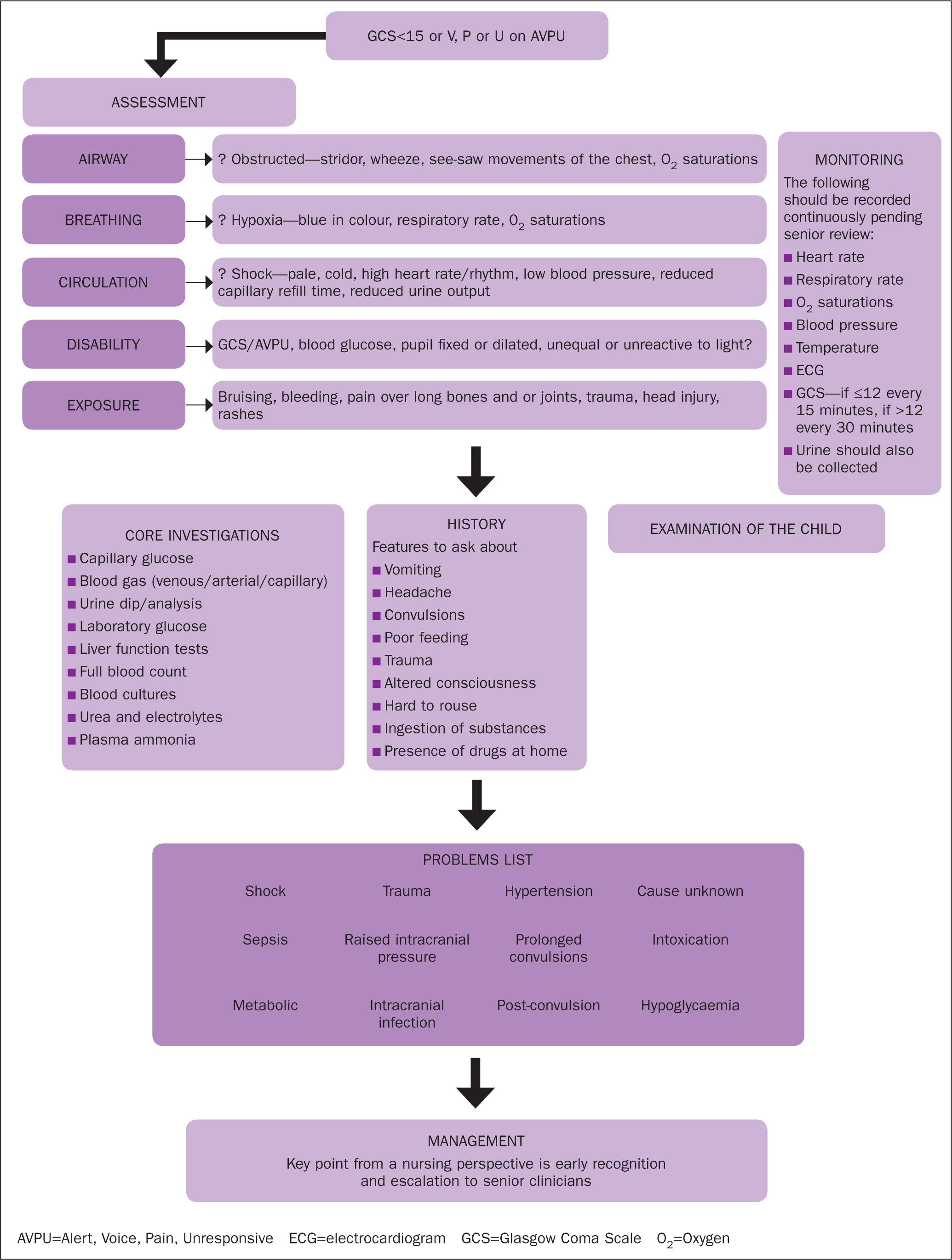

A structured approach should be taken when managing a child with dLOC in an emergency setting. Simultaneous resuscitation, diagnosis and treatment should all be initiated without delay (Tintinalli et al, 2015). The goals are to stabilise the patient as well as to establish the cause of dLOC and prevent deterioration by administering the correct emergency management (Chan et al, 2013; Reynolds et al, 2018). Figure 1 shows an algorithm for initial and empirical management of a child presenting with dLOC.

Any abnormalities should be treated as they are identified, as with the assessment of any sick child; for example, when assessing the airway and breathing, if the patient is found to have an occluded airway or found to be hypoxic these should be corrected immediately before moving on with the rest of the ABCDE assessment. Airway, breathing and circulatory problems should initiate an immediate review by a senior clinician, as should dLOC, signs of severe injury, infective-appearing rashes and major sources of bleeding.

History

It is important to ask relevant questions on the clinical presentation that explore prodromal events leading to the episode of dLOC with reference to the wide differential diagnoses (Chan et al, 2013; Tintinalli et al, 2015; Reynolds et al, 2018). General questions should be asked regarding developmental milestones, past medical history, travel, medication available in the household (including recreational drugs), immunisation and family history.

Some key questions that should be considered when dealing with a child with dLOC include (Chan et al, 2013; Reynolds et al, 2018):

Physical examination

When a child arrives in the emergency department (ED) with dLOC an ABCDE approach should be taken. ED nurses are often the first health professionals to see these children, and should focus on early identification of dLOC followed by appropriate escalation given the serious and wide nature of the differential diagnoses.

A full set of observations and continuous monitoring should be applied. Particular care should be applied when evaluating vital signs such as temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturations and respiratory rate, which are often the most sensitive indicators of an acutely unwell patient (Table 2). A paediatric early warning score/system (PEWS) is used in most hospitals in the UK to help evaluate vital signs and enable the early recognition of sick children—there is not, as yet, a standardised chart but it is suggested that the local version is used for this purpose. It is equally as important to observe any change in the child's level of consciousness compared with their pre-hospital state as well as their posture, size and reactivity of pupils, tone and reflexes.

| On first assessment and then hourly |

|

| Continuous monitoring |

|

| Record consciousness level using AVPU or GCS |

|

A full clinical examination would need to be undertaken by an appropriately trained health professional to identify any abnormalities that could point towards a definitive cause of dLOC. Bruising, signs of neglect, or other signs of trauma may suggest non-accidental injury. Rashes or skin lesions can be manifestations of certain infections (eg non-blanching petechial/purpuric rash in meningococcal septicaemia or vesicular rash in chickenpox). Neurocutaneous stigmata can be associated with genetic conditions that predispose individuals to epilepsy (eg neurofibromatosis or tuberous sclerosis). Full exposure of the child is of critical importance to identify any obvious pathology; care must be taken when doing this, with a chaperone present. If there are any concerns regarding non-accidental injury these should be immediately escalated to a senior paediatrician while managing the symptoms, eg raised intracranial pressure or skull fracture in abusive head trauma (Payne et al, 2017).

Investigations

All children who present with dLOC are best investigated with a core set of tests, as outlined in Figure 1. These investigations can provide insight into the status and prognosis of a patient (Bowker et al, 2007; Song and Wang, 2017). In children who present with dLOC, a capillary blood gas should be undertaken within 15 minutes of presentation (Desachy et al, 2008; Tintinalli et al, 2015). Blood bicarbonate and lactate levels may provide useful information in cases of shock, sepsis, trauma, respiratory distress, metabolic disorders or suspected acid-base imbalance. In cases where sepsis remains a differential diagnosis, urinalysis, white cell count, platelet count; blood cultures (meningococcal and pneumococcal PCR depending on clinical presentation), and C-reactive protein (CRP) would all be a useful set of investigations. In suspected cases of intoxication, poisoning or drug overdose it is useful to take samples of blood and urine, which can be analysed later for specific substances, such as opiates or tricyclics.

Treatment

From a nursing perspective, early stabilisation of these patients can buy valuable time, and be lifesaving. Addressing issues that arise in the ABCDE assessment is vital. Applying a chin lift jaw thrust to open up an airway, being mindful of any potential C-spine trauma, sitting up a patient to help them to breathe better or raising a patient's legs and lying them flat to help with restoring blood flow to the brain, stabilising a patient's C-spine, keeping them safe during a convulsion, and carrying out the ‘sepsis six’ (giving oxygen, fluids and antibiotics, taking lactate, cultures, and measuring urine output) are all basic but potentially lifesaving forms of treatment. In cases where raised intracranial pressure is suspected, raising the patient's head to 30 degrees is another simple manoeuvre that could buy clinicians and patients critical time.

The role of the nurse

Prognosis and outcomes of children presenting with dLOC are largely dependant on the cause. However, it is known that early recognition of the cause and escalation to senior clinicians does make a difference to prognosis and outcomes. It is imperative for nurses to remain aware of the common causes of dLOC, be familiar with the important features and initial management, and the need for early escalation to ensure timely treatment.

An overview of the different roles of nurses who may encounter children with dLOC is given in Table 3.

| Nurse | Role |

|---|---|

| School and community |

|

| Practice nurse |

|

| Emergency department nurses |

|

| Children's nurses |

|

| Health visitors |

|

| Paediatric intensive care unit nurses |

|

Case studies

Case 1

History: A 10-week-old baby was brought to the ED having been found unresponsive by the mother, and given cardiopulmonary resuscitation by the father. She was born at full term, following an uncomplicated pregnancy, by normal vaginal delivery and had no previous symptoms.

Examination: Resuscitation was commenced using an ABCDE approach; the baby was deeply unconscious. The chest was clear with equal air entry with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/minute and oxygen saturations 90% on face-mask oxygen. The baby had a pulse of 80 beats/minute, a blood pressure of 112/44 mmHg with a central capillary refill time of 3 seconds and normal heart sounds. There were no rashes or bruises. The anterior fontanelle was tense and non-pulsatile. The temperature was 36°C. The triage nurse contacted the hospital paediatric emergency team. The baby exhibited Cushing's triad with decreased respirations (caused by impaired brainstem function), bradycardia and systolic hypertension (widening pulse pressure), which is usually seen in terminal stages of acute head injury and may indicate imminent brainstem herniation.

What is the immediate priority intervention? Secure airway and ventilation. The patient will need urgent intubation and medical care.

What are the urgent investigations? CT scan of head, basic blood tests (see Figure 1).

What other steps would need to be initiated? Safeguarding procedure will be needed, the triage nurse identified via the system the family's previous involvement with the child safeguarding team, and the parents were recurrent attenders themselves with vague symptoms and unexplained injuries.

Comment: Ophthalmoscopy revealed extensive bilateral retinal haemorrhages. The CT scan showed bilateral subdural haematomas and extensive cerebral injury. Multiple fractures of long bones and ribs were seen on skeletal survey. The baby died; safeguarding and criminal proceedings were initiated by appropriate agencies. In non-accidental injury a full and complete history may be lacking, and sometimes extensive internal injuries, such as intracranial bleeds, may not show any external signs.

Case 2

History: A 10-year-old boy was admitted with agitation and confusion. He had been perfectly well a few hours previously and was on holiday at a caravan park.

Examination: Following an ABCDE approach he was found to be acutely agitated and combative. His airway was patent and he was screaming. He had a respiratory rate of 25 breaths/minute, oxygen saturations of 98% in air. There was equal air entry bilaterally on auscultation of his chest. He had a heart rate of 170 beats/minute with a blood pressure of 196/127 mmHg and normal heart sounds. His temperature was raised at 38.2°C, there were no skin lesions or rashes. His pupils were widely dilated and he was responding to voice.

What is the immediate priority intervention? Ensure airway patency and preparation for supporting airway to be initiated. The patient will need medical care including blood pressure management.

What are the likely differential diagnoses? Acute intoxication, previous undiagnosed renal disease given the hypertension, infection, increased intracranial pressure.

What investigations might be helpful? Basic haematology and biochemistry, urinalysis, urine toxicology (see Figure 1).

What other steps would need to be initiated? Safeguarding procedures, investigations into possibility of undiagnosed chronic illness

Comment: All basic investigations were normal. Urgent urine toxicology was strongly positive for amphetamines. Patient persistently denied being given, or having taken, any drugs or medication; no concerns regarding home circumstances. Likely ‘Ecstasy’ (MDMA) overdose.

Conclusions

The child presenting with dLOC can be clinically unstable and pose a diagnostic challenge for all healthcare staff. Conditions leading to dLOC in a child can be responsible for high mortality rates. It is important to identify the key features in the history and examination that can lead towards a likely set of differential diagnoses. A management plan following an ABCDE approach will need to be initiated while a specific diagnosis is being sought. In cases where there are no distinguishing features, early supportive treatment and a sepsis bundle need to be followed and potential unidentified or undisclosed trauma should be investigated.