Wounds pose a significant burden to patients as well as the health economy. They can often be hard to heal, resulting in a cycle of pain, anxiety and reduced quality of life for individuals affected as well as consuming significant healthcare resources to treat.

In a recent study (Guest et al, 2015) the annual cost to the NHS in the UK attributable to wound management and associated comorbidities was estimated to be £5.3 billion. Delayed wound healing and wound complications add considerably to the cost of care and are associated with longer and more intensive treatment, extended hospital stays or readmission and a need for specialist intervention (Dowsett, 2015). The resources required to manage unhealed wounds are significantly greater than that of managing healed wounds, and non-healed wounds in the community require an extra 20% more practice nurse visits and 104% more community nurse visits (Guest et al, 2017).

The demographics of patients presenting to the NHS for wound care has significantly changed over the last decade. There has been an expansion in the ageing population, resulting in patients with increasing comorbidities, which impact on the ability of a wound to heal (Guest et al, 2015; Evans, 2017). In particular, the rising national and international rates of significant diseases that directly affect wound healing, such as obesity and diabetes further compound the problems of wound management (Frykberg et al, 2015). As a result of these changing demographics, the demand for wound care services has increased. Data on expenditure on health service suggests that funding of healthcare is unlikely to keep pace with demand and that fundamental changes will need to be made in the way wound care is delivered in the future if we are to reconcile supply with demand (Dowsett et al, 2014).

The pathophysiology of wound healing

Although classically described as a continuous timeline of discrete events, wound healing is actually a highly dynamic process with wounds progressing, stagnating and regressing through three predictable stages: haemostasis inflammation, proliferation and maturation (Stadelmann et al, 1998).

Interruption of these processes can lead to non-healing, chronic wounds and an early assessment to identify causative, or contributing factors, with the potential to delay, or prevent tissue viability and healing is essential. In normal physiology the body uses ‘dry healing’, with formation of a solid, impermeable scab that blocks epithelial cells from proliferating over the wound bed. Winter et al first introduced the concept of ‘moist wound healing’ by recognising that moist occlusive, or semi-occlusive environments allow wounds to heal at twice the rate of dry healing (Winter, 1962). Specifically, he was the first to recognise that an aqueous environment is essential for cell growth, metabolism and regeneration.

How to manage acute wounds and prevent progression to chronicity

Wound healing can be affected by intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Sussman, 2014; Stacey, 2016). Intrinsic factors include physiological states such as tissue oxygenation, immune function, nutritional status, increasing age (and with it the loss of collagen) and patient co-morbidities altering the body's immune response. To modify intrinsic factors, patients must have their physiology optimised with control of comorbidities and adequate nutritional support (using, for example, the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) to identify those who are malnourished).

Extrinsic factors relate to the wounds themselves and include: physical damage (pressure, friction or shearing forces); debris (slough, necrotic tissue or eschar within the wound bed); desiccation (drying of the wound resulting in surface-cell death); maceration (excessive exudate damaging the peri-skin) and infection (ca using adverse chemical states). Diabetes in particular can have a detrimental effect on wound healing as microangiopathic disease results in impaired blood flow and subsequent poor tissue oxygen delivery. Additionally, peripheral neuropathy predisposes patients to trauma with an increased risk of secondary infection due to their decreased immune function. Furthermore, diminished collagen synthesis and poor tensile strength within tissues leads to an increased risk of wound dehiscence (Eagle, 2009; Stacey, 2016).

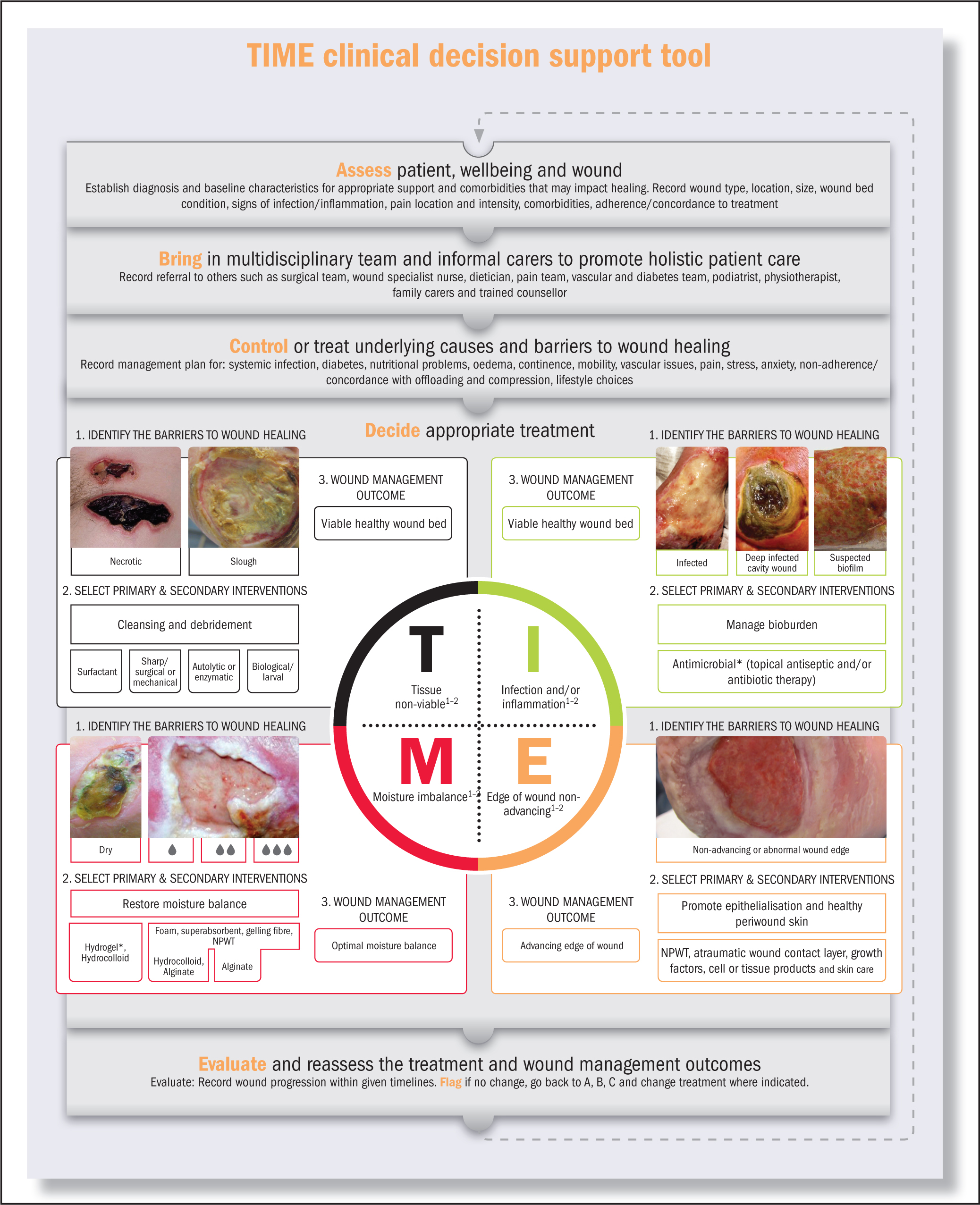

Wound assessment and management frameworks such as T.I.M.E and decision-making support tools described in this article offer clinicians an opportunity to improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden of chronic wounds.

Wound bed preparation and T.I.M.E

The concept of wound bed preparation has gained international recognition as a framework that provides a structured approach to wound assessment and management (Falanga, 2000; Schultz et al, 2003; Leaper et al, 2012). Wound bed preparation focuses on the critical components of wound healing, including debridement, bacterial balance and management of exudate, taking into account the overall health status of the patient and how this may impinge upon the wound healing process. The T.I.M.E paradigm (tissue, infection, moisture balance and edges of wound) (Table 1) was developed in 2002 by an international expert group of clinicians and researchers to facilitate implementation of wound bed preparation into clinical practice (Schultz et al, 2003). The T.I.M.E principle has been widely adopted into practice and research (Dowsett, 2008; Leaper et al, 2012; Sibbald et al, 2015; Harries et al, 2016; Teobaldi and Mantovani, 2018) and has been shown to improve knowledge and clinical practice when used as part of a structured educational programme in community nursing (Dowsett, 2009).

| T | Represents the tissue type in the wound. Is it viable or non-viable? |

| I | Refers to the presence or absence of infection and/or inflammation |

| M | Addresses the issue of moisture balance, to avoid desiccation or maceration |

| E | Refers to the wound edge. Is this advancing appropriately towards wound closure? |

Probably one of the key reasons why T.I.M.E has proved to be a popular and enduring paradigm is that it provides an algorithmic method that practitioners can use to identify key elements that may be preventing a wound from healing. A recent survey identifies T.I.M.E to be a useful tool in practice and it has been found to be the most commonly used wound assessment tool in Europe (Ousey et al, 2018).

The importance of T.I.M.E and wound bed preparation in acute wounds

All wounds, at some point in their pathogenesis are acute, irrespective of their aetiology. What differentiates them is that acute wounds follow a normal trajectory towards complete healing, while chronic wounds stagnate along the healing pathway and can get ‘stuck’ in one of the phases described above. Oftentimes this is due to compromise from either intrinsic or extrinsic factors listed above, or quite often a combination of the two. Typically, an acute wound becomes ‘chronic’ when it fails to heal within 4 weeks or shows little-to-no signs of healing by 8 to 12 weeks (Whitney, 2005). The importance of wound bed preparation in an acute setting includes thorough inspection of the wound bed to remove any foreign bodies that may act as a nidus of infection, or crushed/devitalised tissue that can impede wound closure. The presence of non-viable tissue in a wound bed obscures accurate assessment of the depth of the wound and condition of the tissue contained therein. Additionally, bacterial contamination or colonisation is more common in the early stages of acute wounds, appropriate debridement (using surgical, mechanical, autolytic, enzymatic or biological techniques) should be performed as bacteria can compete with regenerative cells for the scarce local resources such as oxygen, needed for wound healing (Halim et al, 2012). The aim of wound bed preparation is to restore a viable wound base that can progress to healing and the removal of senescent cells, biofilms and inflammatory enzymes through debridement can thus also convert a chronic wound into an acute wound (Panuncialman et al, 2007).

Over the past decade, there have been considerable advancements in wound care technologies and T.I.M.E has maintained its relevance by being responsive to such developments. It encourages the use of repetitive/maintenance debridement (Strohal et al, 2013; Price and Young, 2014), recognises the infection continuum and the concept of wound biofilms (Percival et al, 2015) and advocates the use and development of advanced dressings/therapeutics such as negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) (Ubbink et al, 2008). As such, the developments in wound management have helped reinforce the need for, and clinical relevance of, the T.I.M.E paradigm.

T.I.M.E to improve clinical decision making

The decisions clinicians make when assessing and managing patients with wounds can have either a positive or negative impact on the patient, their wound and the wider healthcare economy. Poor decision making can lead to inappropriate treatments, wound complications such as infection and protracted healing times. Guest et al (2017) identified that 30% of all wounds being managed within the NHS lacked a differential diagnosis and only 16% of patients with lower leg, or diabetic foot ulceration underwent a vascular assessment with a Doppler to measure ABPI. Of particular concern was that dressing and bandage types were repeatedly switched at successive wound dressing changes, indicating confusion and conflict within the treatment plan. In a recent cross-sectional survey of complex wounds and their care in a UK community population, Gray et al (2018) found indicators that revealed unwarranted variation in clinical practice across participating services; the underuse of evidence-based interventions such as compression therapy for venous ulcers and the overuse of interventions supported by limited evidence (e.g., antimicrobial dressings). The implications of poor management of wounds are far-reaching and involve both the individual patient and the healthcare system as a whole. In a study by McCaughan et al (2018), wound associated factors were found to have a profoundly negative impact on daily life, physical and psychosocial functioning, and wellbeing. Furthermore, participants expressed dissatisfaction, with a perceived lack of continuity and consistency of care in relation to wound management.

T.I.M.E offers clinicians an opportunity to address these deficits in care but needs to be considered within the context of a thorough patient assessment, accurate diagnosis and ongoing evaluation of the outcomes of treatment interventions. One of the earlier criticisms of the T.I.M.E paradigm was that it was too ‘wound focused’ and failed to recognise the importance of patient-centred care. In an attempt to address this, a wound bed preparation care cycle (Figure 1) was developed to promote re-assessment and changes in wound care treatments in response to wound progression or regression (Dowsett, 2004; Dowsett and Newton, 2005).

The T.I.M.E clinical decision support tool

Recently the T.I.M.E paradigm has been revised and expanded to incorporate the development of a clinical decision support tool (CDST), further supporting the concept of holistic wound care and involvement of the multidisciplinary team as well as emphasising the need to evaluate the treatment and the wound management goals. Results of a survey of 196 participants at the European Wound Management Association (EWMA) 2018 conference (Ousey et al, 2018) showed that although T.I.M.E was the most commonly used assessment tool, application was often inconsistent and erratic. The results of this survey informed the development of the CDST, which was further developed and refined by an International group of expert clinicians at a recent consensus meeting in London, September 2018.

The T.I.M.E CDST offers an A<B<C<D and E approach (Figure 2) as follows:

Accurate and timely assessment as well as re-assessment is an essential element of effective wound care (Edwards et al, 2018). The reality of nursing practice is that there are often delays in this critical process due to the demands of increasing caseloads and a reduction in the number of nurses. Research by the King's Fund in 2016 indicated that district nursing activity has increased significantly over recent years, both in terms of the number of patients seen and the complexity of care provided (Maybin et al, 2016). While demand for services has been increasing, available data on the workforce indicates that, certainly in a community setting, the number of nurses working in community health services has declined over recent years, and the number working in senior ‘district nurse’ posts has fallen dramatically over a sustained period. There is a strong concern that these pressures are compromising quality of patient care delivered, with an increasingly task-focused approach to care, visits being postponed and lack of continuity of care (Maybin et al, 2016). In an attempt to improve wound assessment in the community setting the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) framework, introduced by the Department of Health, specified ‘Improving the assessment of wounds' as a key goal of the CQUIN scheme for 2017–2019 (Scott-Thomas et al, 2017), and many community nurses are working to deliver on this CQUIN.

Given the complex nature of many patients with wounds, it is of paramount importance to bring in the multidisciplinary team to ensure all aspects of patient care are addressed to treat the underlying cause and promote wound healing. The World Health Organization (WHO) argued that professionals who actively bring the skills of different individuals together, with the aim of clearly addressing the healthcare needs of patients and the community, will strengthen the health system and lead to enhanced clinical and health-related outcomes (WHO, 2006). Indeed, a number of systematic reviews and individual clinical studies have noted a positive impact in the use of multidisciplinary teams for a variety of clinical conditions, including wounds of varying aetiologies (Moore et al, 2014).

It is well known within both clinical practice and research, that to appropriately manage individuals with wounds the next step following assessment and diagnosis, is to address and modify, control and treat systemic causes and comorbidities, where possible (Frykberg and Banks, 2015). For example, off-loading is a key treatment strategy for the management of diabetic foot ulceration. A systematic review summarised the evidence for off-loading and identified that healing rates, healing times and reduction in ulcer size were improved with the use of total contact casting (de Oliveira and Moore, 2015). Furthermore, in the management of individuals with venous leg ulcers, compression therapy is a fundamental intervention to address the underlying venous disease (O'Meara et al, 2012).

Deciding on the most appropriate treatment modality clearly links the T.I.M.E assessment framework to available treatment option by ensuring that wound bed preparation is appropriately addressed. For example, the development of a significant bioburden is a barrier to healing for all wounds (Jones and Kennedy, 2012). Recent developments in the assessment and management of biofilms highlight the importance of early intervention and the use of multi-modal therapies, including debridement and effective use of antimicrobials (Schultz et al, 2017). Treatment recommendations based on local dressing formularies can be incorporated into the CDST to ensure patients receive the most appropriate treatment based on individual clinical need.

Evaluation and reassessment of the treatment and wound management outcomes completes the first cycle (given that wound management often involves repeating the cycles of assessment and evaluation) in the wound assessment and management trajectory, focussing attention on the role of evaluation in assessing goal attainment (Moore et al, 2016). Wound measurement forms part of this evaluation and when the wound edge fails to progress, advice should be sought from a wound care specialist as part of multidisciplinary team working.

Future proofing the T.I.M.E CDST

Fundamentally, wound management is an ever-evolving specialty (Leaper et al, 2012). As such, assessment and management algorithms developed today need to ensure they are ‘future-proofed’ to readily respond to emerging technologies and interventions (International Consensus, 2013). In order to ensure future proofing of the T.I.M.E CDST, consideration has been given to a number of key elements:

The principles of the CDST are not new to healthcare providers. Many nurses caring for patients with wounds are already using the T.I.M.E paradigm in practice and therefore are in a position to expand their scope of practice to include the T.I.M.E CDST as an opportunity to improve the outcomes of their patients.

Conclusion

Patients with wounds and their associated problems pose an important healthcare challenge. Wounds are costly for both the patient and the health economy and place a significant demand on nursing time. Delays in wound healing can be perpetuated by poor treatment choices, and a failure to recognise complications and/or seek timely advice. Improving patient outcomes requires a proactive approach to care that includes accurate and timely assessment, treatment of underlying cause and the use of evidence-based practice in combination with clinical judgement and experience to plan the most appropriate treatment. A structured approach to care such as the T.I.M.E paradigm and clinical decision support tools such as the proposed T.I.M.E CDST in this paper have the potential to improve wound healing outcomes and reduce the overall burden of wounds to patients and healthcare services.