There is an urgent need for nurses across all healthcare services to address the detrimental impact that healthcare practices have on the environment. The NHS accounts for about 4% of total carbon emissions in England (NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2020). Around 60% of NHS emissions are generated from the Supply Chain (Tennison et al, 2021), the equipment used in hundreds of thousands of procedures every day. The manufacture of some pieces of disposable equipment, such as sterile gloves, are damaging to the environment (Jamal et al, 2021). In 2019, the health service's emissions totalled 25 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), a reduction of 26% since 1990 (Tennison et al, 2021). This demonstrates that the NHS has been working to reduce its carbon emissions (Watts et al, 2021) but much more must be done. Disposal of waste generates further carbon emissions, with high-temperature incineration of clinical waste producing the highest emissions at 1074 kg tCO2e (tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent) (Rizan et al, 2021). A further 15% of NHS waste is sent to landfill (Rizan et al, 2021).

Nurses have a pivotal role to play in reviewing their practice, not only ensuring that practice is evidence based, but that it is sustainable. Aseptic techniques are one area of practice where the use of consumables, and subsequent waste, may be high. Traditional sterile techniques are variable and poorly understood, leading to inconsistencies in practice (Gould et al, 2018). However, the Aseptic Non-Touch Technique (ANTT®) Clinical Practice Framework (Clare and Rowley, 2018) provides a useful structure for infection prevention practice in all settings. Crucially, the implementation of Standard-ANTT® may reduce the amount of waste generated in a procedure and lead to the use of consumables that are less damaging to the environment, such as non-sterile gloves (Jamal et al, 2021).

Nevertheless, changing practice from so-called sterile technique or Surgical-ANTT to Standard-ANTT may be challenging. In the administration of parenteral nutrition (PN), connection and disconnection of the PN infusion is an area where traditional mindsets and techniques persist (Cawley and Small, 2023), although an ANTT and the protection of Key-Parts has been advocated for some time. The ANTT principles, which include rigorous hand hygiene, decontamination and protection from contamination, form the foundation of all aseptic procedures (Loveday et al, 2014). The connection of PN to a central venous access device (CVAD) is no more technically difficult than connecting a bag of normal saline; Key-Parts are easily protected using a non-touch technique and non-sterile gloves.

The authors’ institution is a large, tertiary referral centre for multiple specialties. Standard-ANTT for administration of intravenous therapies, including PN, was implemented some years ago. This change allowed standardisation of practice and training across the organisation (Department of Health, 2022). However, to date, no comparative analysis of the volume of waste saved from this change in practice has been carried out. An estimate of the volume of waste saved in the administration of PN using Standard-ANTT rather than a sterile technique (Surgical-ANTT) is a first step in quantifying this.

Aims

To measure and compare the volume of waste generated from sterile technique or Surgical-ANTT and Standard-ANTT in the administration of PN.

Methods

The British Intestinal Failure Alliance (BIFA) Standardised Parenteral Support Catheter Guidelines for the connection and disconnection of PN (Cawley et al, 2018) were used as a broad structure for each procedure. Although emphasising the need to protect Key-Parts, the BIFA guidelines follow a sterile technique. However, the BIFA guidance is not dogmatic and acknowledges that hospitals may vary practice locally. The BIFA process was followed, using a dressing pack and sterile gloves according to historical practice in this institution. However, the use of tape to secure the sterile towel was excluded as not previously used in aseptic technique at the authors’ institution.

For the Standard-ANTT procedure a general aseptic field, micro-critical aseptic field and non-sterile gloves were used. Steps from the BIFA guidelines process that were not required/relevant in Standard-ANTT were excluded during the ANTT simulation: these were use of a sterile drape, use of a sterile towel to place under the cleaned central venous access device (CVAD), and use of gloves to spike the bag of PN.

Equipment

In a simulation, two procedure trays were set up with the equipment to carry out administration of PN, one using a sterile technique and one for Standard-ANTT.

All equipment packaging, covers and caps were retained for weighing.

Weights

All consumable items and retained packaging were weighed from each procedure using Digi™ digital bench scales, model DS-502, serviced and calibrated within the previous 3 months.

All weights were recorded in grammes (g) and checked by two investigators independently for accuracy and agreement.

After weighing, all used items were retained for future staff training so as not to generate waste from the study.

Some consumable items that would be used routinely in both clinical procedures for the administration of PN were not weighed. These included handwashing equipment, apron, bag of PN and detergent wipes used to clean the tray and work surfaces.

Results

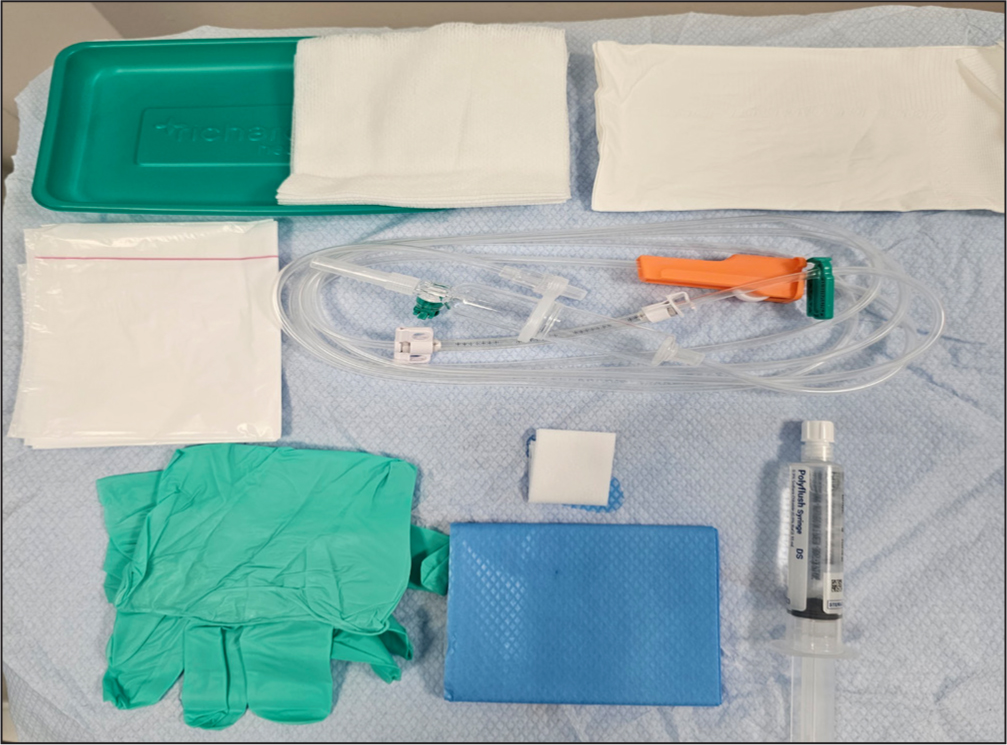

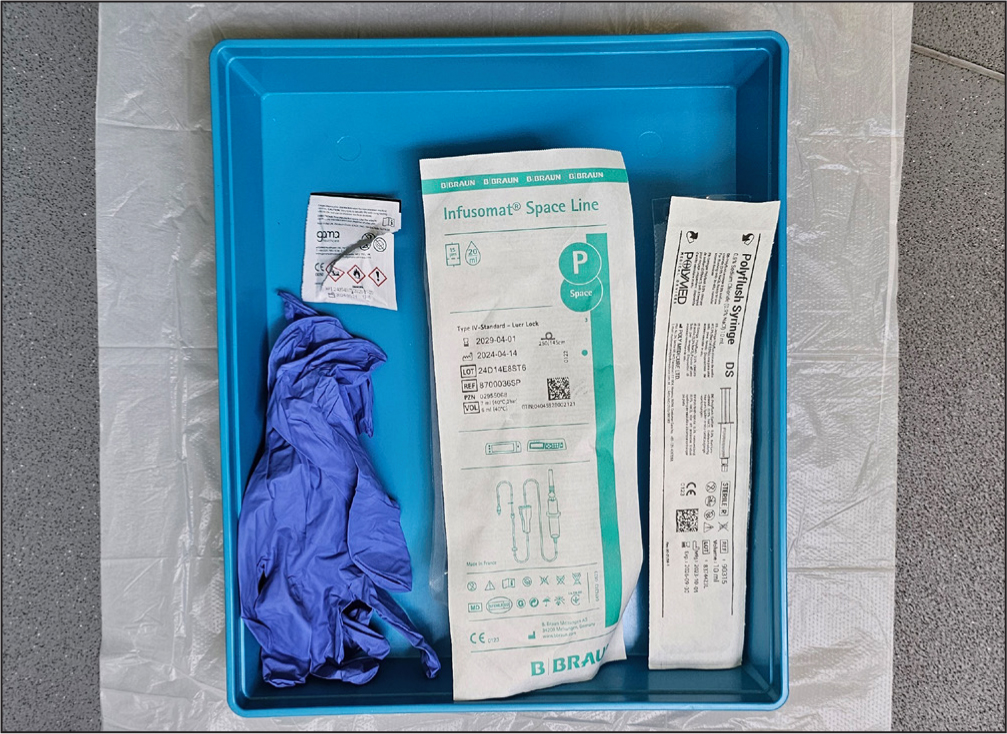

Consumable items used in the traditional sterile technique (Surgical-ANTT) are listed and illustrated in Table 1 and Figure 1. The weight of these items, including packaging, was 129 g. Table 2 and Figure 2 show the consumable items used in Standard-ANTT in the administration of PN. Total weight of these items, including packaging, was 62 g. Table 3 shows the weight of individual items and the total weight of consumable waste for each procedure.

| Sterile dressing pack components* | Use in the sterile technique |

|---|---|

| Plastic tray | May be required during wound care or a dressing change for holding a wound-cleansing solution |

| 5 × pieces of gauze |

May be required during wound care or a dressing change for cleansing or dressing a wound |

| Plastic disposal bag | May be required during wound care or a dressing change for easy disposal of used dressings |

| Sterile drape | May be required during wound care or a dressing procedure, or other procedure |

| Sterile towel | Placed under the cleaned CVAD to protect the Key-Part |

| Sterile field | Critical sterile field on which to open sterile items |

| 1 × pair medium sterile gloves | For handling sterile items |

| Other consumable items not in the dressing pack | |

| 1 × 2% CHG in 70% IPA wipe | For cleaning the CVAD hub (Loveday et al, 2014) |

| 1 × pre-filled 0.9% sodium chloride syringe | For flushing the CVAD |

| 1 × pair medium non-sterile gloves | To spike bag of PN |

| 1 × intravenous infusion pump administration set | For administration of PN |

Key: 2% CHG in 70% IPA=2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol, CVAD=central venous access device, PN=parenteral nutrition

| Consumable item | Use in Standard-ANTT |

|---|---|

| 1 × 2% CHG in 70% IPA | wipe For cleaning the CVAD hub (Loveday et al, 2014) |

| 1 × pre-filled 0.9% sodium chloride syringe | For flushing the CVAD |

| 1 × pair non-sterile gloves | For handling clean items |

| 1 × intravenous infusion pump administration set | For administration of PN |

Key: 2% CHG in 70% IPA=2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol, CVAD=central venous access device, PN=parenteral nutrition

Note: a sterile towel may be placed under the cleaned CVAD if it is not possible to protect the Key-Part. However, this is not standard practice

| Consumable item | Weight in grammes (g) | Sterile technique | Standard-ANTT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sterile dressing pack with contents and packaging | 67 | 67 | n/a |

| Individual items from the dressing pack (minus external packaging): | 7 | − | n/a |

| Plastic tray | 6 | ||

| 5 × pieces of gauze | 5 | ||

| Plastic disposal bag | 11 | ||

| Sterile gloves | 10 | ||

| Blue drape | 6 | ||

| Sterile towel | 7 | ||

| Sterile field | |||

| 1 × 2% CHG in 70% IPA wipe and packaging | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 1 × pair of medium non-sterile gloves | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 1 × (empty) intravenous infusion pump administration set and packaging | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| 1 × (empty) pre-filled 0.9% sodium chloride syringe and packaging | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Total weight (g) | − | 129 | 62 |

| 1 × pair medium sterile gloves and packaging (separate to the dressing pack) | 16 | Optional | n/a |

Consumable equipment used in the Standard-ANTT procedure weighed 67 g less than the traditional sterile technique. The weight of a separate pair of sterile gloves is shown as an example for comparison if an additional pair of sterile gloves were used to spike the bag of parenteral nutrition, or if sterile gloves were contaminated during the procedure and required changing during the aseptic technique procedure

Key: 2% CHG in 70% IPA=2% chlorhexidine gluconate in 70% isopropyl alcohol

The difference in weight of consumable items including packaging was 67 g, with Standard-ANTT generating 52% less waste that the traditional aseptic technique.

Annual weight of consumable waste saved by using Standard-ANTT

During 2023-2024 the authors’ institution recorded 439 inpatients who were prescribed PN, with an estimated 7300 catheter days. If it is assumed that each catheter day represents administration of one bag of PN, the weight of consumable waste over the year can be estimated:

It is estimated that, in a year, a total of 489 kg of consumable waste was saved by using Standard-ANTT instead of a sterile or Surgical-ANTT in the administration of PN.

Carbon emissions

If it is assumed that items from the administration of PN procedures are disposed of in clinical waste, then the saving in carbon emissions can be estimated:

Discussion

This comparative analysis demonstrated a significant reduction in waste from a relatively straightforward change in nursing practice. The subsequent reduction in carbon emissions and related costs to the NHS over a sustained period are likely to be substantial. It is recognised that, for the total annual waste and carbon saving example, PN may not have been given every day due to patient variation and that 2023-2024 was one of the busiest periods recorded at the authors’ institution. Nevertheless, it remains clear that substantial total annual reductions are possible. Similar changes made across other NHS organisations could have a tangible and positive impact on reducing the NHS carbon footprint.

With approximately 88% of hospitals in England and 100% of Welsh hospitals adopting ANTT as their single standard aseptic technique (Rowley and Clare, 2020), applying these principles to PN administration is practically and logistically achievable. Nevertheless, the perception that patients receiving PN are at higher risk of developing CVAD-related sepsis than those not receiving PN (Beghetto et al, 2005) may hinder changes in practice. Although concerns must be acknowledged, it is important to recognise that more recent evidence does not support this (Gavin et al, 2017). Secondary analysis of a recent randomised controlled trial showed that bloodstream infection rates were evenly spread across patients receiving and not receiving PN (Gavin et al, 2023). The study suggested that mucosal barrier injury was the primary risk factor for CVAD-related sepsis; however, further research is required in this area.

Standardisation of practice has been shown to reduce variation and improve quality of care (Morgan et al, 2015; Oravetz et al, 2019). In terms of aseptic technique in PN administration, the adoption of BIFA Standardised Parenteral Support Catheter Guidelines (Cawley et al, 2018) is an important first step. However, there continues to be scope for local interpretation of the process and use of different pieces of equipment and consumables according to local interpretation. Options determined locally include the use of dressing packs or a sterile towel to create a critical sterile field and choice of gloves (sterile or non-sterile). In terms of sustainability, the current study found that dressing packs generated considerably more waste, with extraneous items not required to administer PN typically included within the pack. The plastic tray, drape and gauze were not used at all and, although convenient, the inclusion of a plastic disposal bag was not necessary for this procedure. Although a variety of different dressing packs that include fewer items may be available, they are all designed for dressings/wound care. Thus, it is likely that most dressing packs will contain items not required to administer PN. According to the BIFA guidance, centres can choose to use a single sterile towel to create a critical sterile field instead of opening a dressing pack to create this, which would be preferable from a waste reduction point of view. Taylor et al (2021) demonstrated how consumable waste could be reduced in the outpatient department by selecting the individual items required rather than using prepackaged procedure packs, which often contain unnecessary items. Nevertheless, with the use of Standard-ANTT a sterile field using a sterile drape is not required at all, reducing waste even further.

Standard-ANTT has been successfully implemented in other areas of PN, such as in training the parents and carers of children having home PN (Mutalib et al, 2015).

In terms of glove usage, Jamal et al (2021) conducted a life cycle assessment comparing the environmental impact of sterile and non-sterile gloves. Sterile gloves were found to have a climate change impact some 11 times greater than non-sterile gloves. Whereas it is thought that sterile gloves offer additional protection against contamination, evidence suggests that non-sterile gloves are equally effective. This includes the use of non-sterile gloves in invasive procedures such as dental surgery (Brewer et al, 2016), minor surgical procedures (Heal et al, 2015), and the suturing of traumatic wounds in the emergency department where the use of sterile gloves and drapes was compared to non-sterile glove use (Zwaans et al, 2022). The connection and/or disconnection of PN is not an invasive procedure and is less technically difficult than the examples discussed. Hence the use of a non-touch technique with non-sterile gloves is logical and well founded in day-to-day practice (Harris, 2023). Moreover, there is further debate regarding whether gloves need to be used at all in procedures that do not expose staff to body fluids, with progress being made in reducing glove use overall (Leonard et al, 2018). From an environmental standpoint this would be the optimal outcome.

Conclusion

This comparative study showed that the use of Standard-ANTT in the administration of PN can reduce waste in this area of practice and estimated potential substantial savings at a large tertiary referral centre. Fundamentally, there is a pressing need for nurses to review practice, and the underpinning evidence, and consider where more sustainable choices can be made.

KEY POINTS

CPD reflective questions

Reflect on the aseptic technique used to administer parenteral nutrition in your institution, and consider the following aspects: