CVCs are essential in modern healthcare, providing access for the safe delivery of medications, fluids, blood products, and other life-saving infusions.3 However, CVC use is not without risks, as CVC-related complications can lead to higher morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. Bloodstream infections are among the most serious of these complications, posing a severe threat to patient safety and the quality of care.4 Additionally, risk of pneumothorax increases when ultrasound guidance is not used to visualize the needle tip during insertion and performing pre- and post-assessment of the sliding lung.5,6

NDCLI programs have emerged as a positive and proactive way to address the challenges of central line insertion delays and management.2 In these programs, nurses use a low-approach insertion technique and carefully direct the catheter down on the chest (see Figure 1). The low approach facilitates greater care and maintenance, serving as a key strategy for maintaining dressing integrity, reducing dressing disruption/changes, and ultimately decreasing central line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI). Suture-less securement devices replace traditional sutures, minimizing tissue trauma and infection, as well as inserter needle stick injury.2,7’8

Historically, central line management has been predominantly physician driven, with physicians assuming device decision and primary responsibility for insertion.

Although the traditional physician-driven model has its advantages, it also presents challenges, such as delays in catheter insertion and variability in practice, particularly when ultrasound is not used. NDCLI programs offer a transformative approach to CVC insertion and management, capitalizing on the invaluable expertise and frontline engagement of nurses. By integrating vascular access teams (VATs) into a multidisciplinary framework, these programs shift responsibility to trained inserters, making CV C procedures a core component of daily practice and patient care. NDCLI programs leverage deep nursing knowledge, refined skills, and comprehensive understanding of individual patient needs, leading to more efficient care without unnecessary delays. NDCLI programs harness the depth of nursing knowledge, honed skills, and intimate understanding of the complexities of each individual patient, increasing efficiency without delay in patient care.

In addition, it allows for standardization in practice and improved patient outcomes. This then leads to improved patient satisfaction, lower healthcare cost, and reduction of length of stay. This initiative represents a significant advancement in the professional development of these highly skilled nurses, to work at the top of their licensure.9 This aligns with the broader trend of enhancing clinical expertise in an era where hospitals are increasingly focused on cost efficiency.

Background

This is a 4-year follow-up of a team expanding the scope of practice to CVC and arterial catheter placement. The initial publication was titled, A Vascular AccessTeam's Journey to Central Venous Catheter and Arterial Line Placement.10 At a time when peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) teams were not focused on expanding their practice to place other vascular access devices (VADs) the VAT at a community hospital in Illinois identified a need to expand their scope of practice to include sites such as axillary/subclavian, internal jugular (IJ), and femoral sites. Arterial catheter insertion was also included as part of their expansion of practice. The journey began when the VAT approached the Illinois Board Nurse Representative and physician advocates who were enlisted to mentor nurses in assuming an expanded role in CVC insertion and management.

Despite initial reservations from some physicians, the interventional radiologists (IR) and intensive care unit (ICU) physicians championed and supported the expansion of an NDCLI program. These physicians witnessed the skill level, knowledge, and acumen of the VAT. Even with this support, it was recognized that catering to diverse patient needs necessitated comprehensive training. Thus, mentors were sought from both specialties and once identified, the next crucial step was participation in a specialized CVC course. Notably, the VAT embarked on the inaugural “Ultrasound-Guided CentralVenous Catheter Insertion” course in 2012, generously sponsored by Teleflex of Morrisville, NC.11 The program focused on reinforcing best practices in CVC insertion for new inserters. It provided the fundamental knowledge required for inserting CVCs taught by well-known practicing practitioners across the nation. Subsequent validation of competencies was managed by the inserters in their individual practice settings. This program included an 8-hour didactic and simulation skills lab.

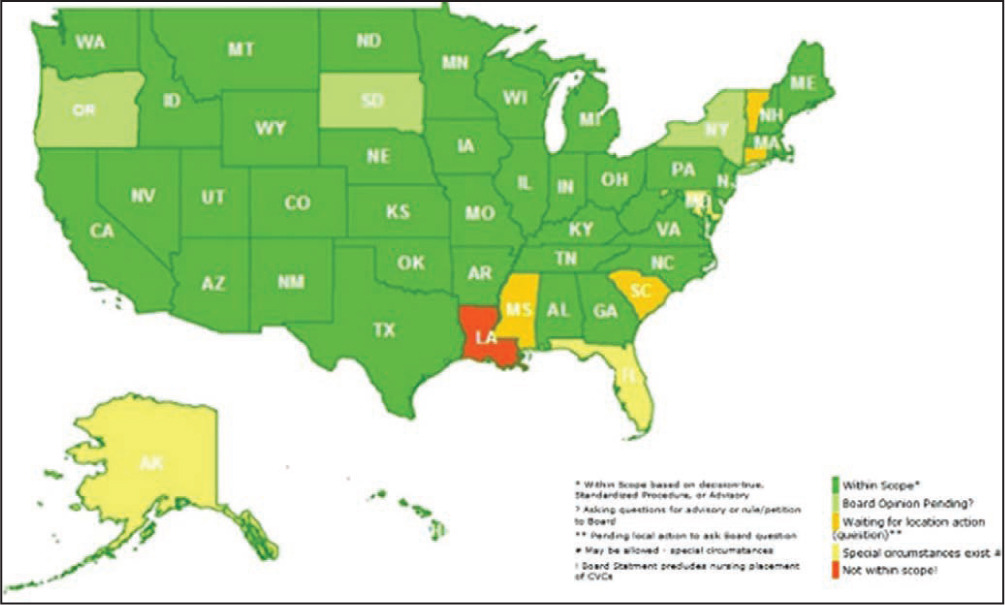

The CVC course covered 4 stations. Station 1 Compliance: Understanding kit components, insertion steps, and the basics of sterile gloving, gowning, and donning and doffing. Station 2 Needling: Taught the ability to “lead” with the needle tip. Station 3 Rapid Central Venous Assessment (RaCeVA)12: A systematic, standardized approach for ultrasound assessment before central venous catheterization. Station 4 Complications: A high-fidelity complication station where physicians drilled down potential complications and interventions. This was far more in depth than the see one, do one, teach one approach that many physicians experience in their practice at that time. Attending the CVC course solidified the reason to move forward with expanding theVATs role within the vascular access point of care. In this community hospital, guidelines including Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI), Appropriateness Guide to Intravenous Catheters (MAGIC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Infusion Nurses Society (INS), and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) were followed and rather than sharing with the doctors that the VAT “could not place a PICC,” theVAT took a multidisciplinary approach with the physicians to advocate for the right device for their patient that could be inserted by theVAT. If an alternative device such as a tunneled catheter was required, theVAT would assist the physician with insertion to build their relationship and knowledge. PICCs were often ordered for the ICU, of which PICCs are considered longterm vascular devices rather than acute care catheters. Factors that make PICCs less than ideal for the ICU are the necessary medications that may lead to vasoconstriction and ultimately failed PICC attempts. In addition, PICC-related thrombosis formation can be attributed to immobility, sepsis, and future vessel occlusions, leading to long-term complications and the inability to have vascular devices inserted in the limb in the future.13 As patients continue to grow in complexity we must also continue to grow in our specialty. This NDCLI program has demonstrated safe and effective patient outcomes. Today there is only one state where CVC insertion by nurses is not permitted (see Figure 2).

Results

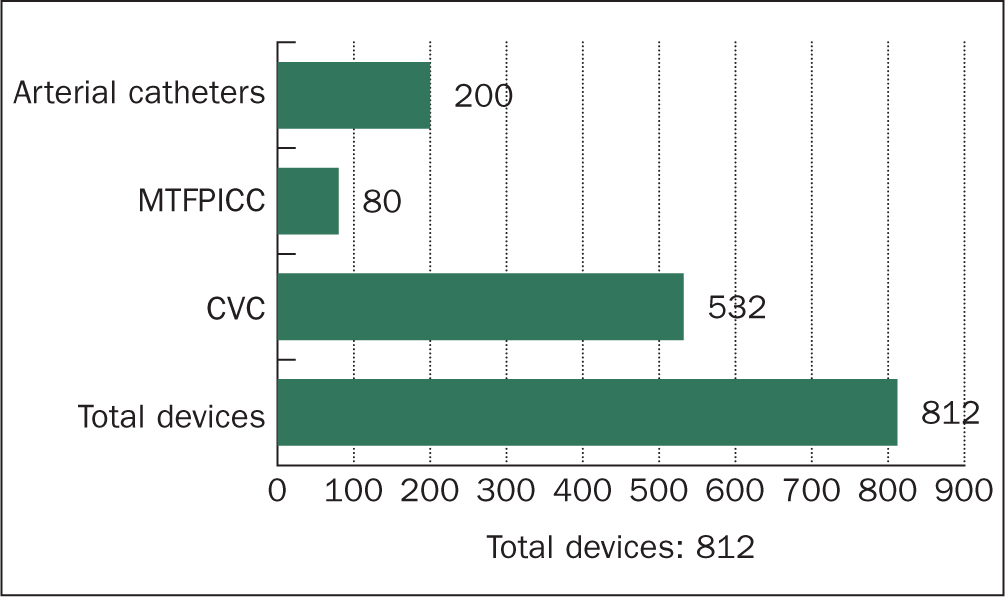

During the 4-year implementation of the NDCLI program at this community hospital, the VAT operated from 8:00 AM to 4:30 PM, Monday through Friday, and from 8:00 AM to 12:00 PM on Saturdays. TheVAT included 1.5 FTEs and one PRNVAN. The data presented excludes the 1200 PICCs and 260 midlines placed annually, focusing solely on CVCs and ACs. Over 4 years, a total of532 CVCs, 80 mid-tight femoral PICCs, and 200 ACs were placed, totaling 812 devices. Notably, midthigh femoral PICCs (MTFPICC) were introduced to the program 2 years after CVC insertion commenced. (see Figure 3). The data was collected using patient data sheets designed to capture pre- and post-insertion information regarding the placement of CVCs. These data sheets were securely stored in a locked office to ensure confidentiality. Subsequently, the data was uploaded into CVADRegistry.com, a national comparative database dedicated to vascular access device placement and management. The database employs triple encryption to maintain data security and privacy.14 This practice aligns with the team's ongoing commitment to collecting consistent comparative data, which is crucial for demonstrating the value of theVATs contributions to vascular access device placement.

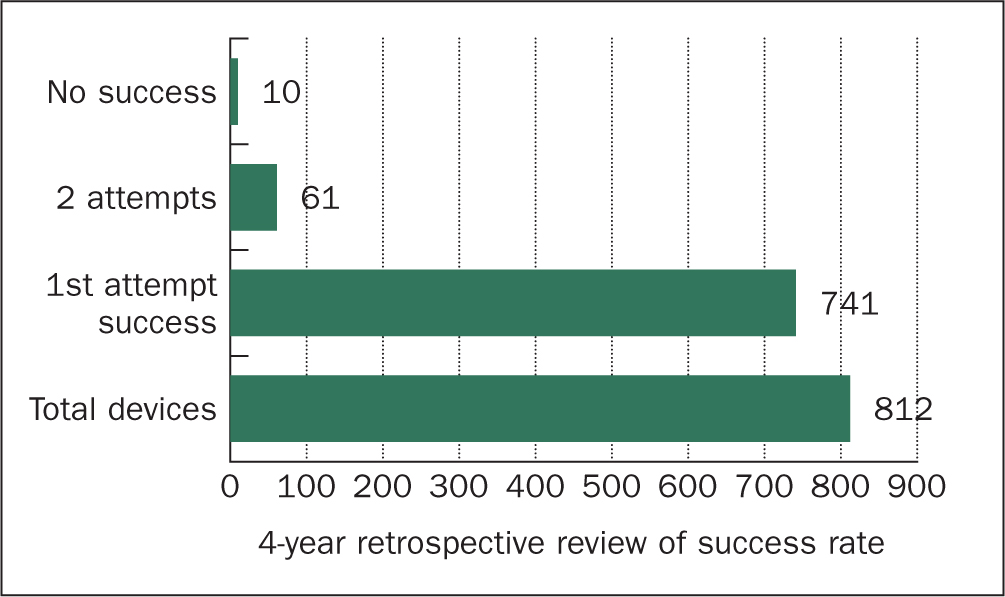

Insertion-related complications were minimal, with only one pneumothorax throughout the 4 years. First-attempt success—defined as a single needle stick with no malposition—was achieved in 91.25% of cases (741 out of 812). Second-attempt success occurred in 7.5% (61 out of 812) of the devices placed, while the failure rate, defined as no success after 2 attempts, was 1.23% (10 out of 812) of placements (see Figure 4).

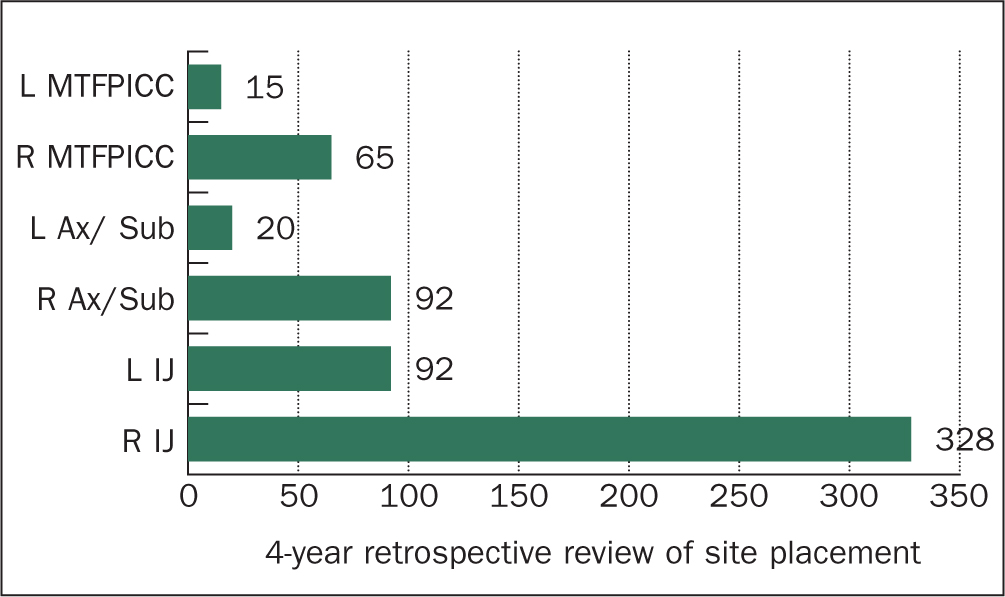

In terms of preferred placement sites, the right side of the patient was commonly chosen due to its more direct and linear pathway to the superior vena cava (SVC), inferior vena cava (IVC), and right atrium, reducing the risk of catheter kinking or resistance. The right internal jugular (IJ) vein was the most frequently used site, accounting for 60.65% (328 out of532) of CVC placements. The left IJ was utilized in 17.3% (92 out of 532) of the cases, while the right axillary/subclavian vein was also used in 17.3% (92 out of532) of CVC placements. The left axillary/subclavian vein was the least used site, accounting for only 3.76% (20 out of 532) of CVC placements (see Figure 5).

Midthigh Femoral Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter

The introduction ofMTFPICC into the NDCLI program was a significant development, prompted by a complex patient case. The patient presented with a left arm fistula, extensive bruising on the right arm from multiple unsuccessful peripheral intravenous attempts, and bilateral upper arm swelling. Additionally, there was visible scarring on the right chest from a recent port removal, alongside multiple puncture sites with granulation tissue on each side of the neck. The only viable access at the time was a right tibial intraosseous device placed 3 hours earlier in the ICU, which was being used for administering vasopressors, 0.9% normal saline, and antiarrhythmic medication.

A RaCeVA confirmed a significant stenosis at the confluence of the right internal jugular, subclavian, and brachiocephalic veins. This assessment identified critical disadvantages and challenges to patient safety and procedural quality of attempting to insert a device at this site. The femoral vein was then assessed and found to be large, compressible, and had a direct pathway to the inferior vena cava, making it a viable option.

In response to these challenges, theVAT collaborated with the ICU intensivist and IR to review and collaborate on the most appropriate device for therapy. During this discussion, the option of placing a MTFPICC, a newer access site in the adult patient population, was proposed. After a thorough and robust conversation among the team members, the decision was made to proceed with a MTFPICC. This device was favored over the traditional femoral CVC due to its placement outside the groin area, specifically at the midthigh, which offered the advantage of keeping the dressing clean, dry, and intact with easy access15 (see Figure 6).

The MTFPICC was then added to the program as an alternative for patients with central vessel occlusions, providing a reliable and less contamination-prone access site.

Discussion

The findings from this 4-year follow-up underscore the significant benefits of implementing a NDCLI program within a healthcare setting. The data presented illustrates the success and safety of the program, particularly in a community hospital environment where CVC and AC insertions were traditionally managed by physicians.

One of the most striking outcomes of the NDCLI program was the high direct-vessel first-attempt success rate (91.25%) in catheter insertions, coupled with a remarkably low insertion complication rate (1.23%). These results affirm the critical role that specialized nursing teams can play in optimizing patient outcomes in vascular access. The introduction of suture less securement devices and the use of ultrasound guidance were key factors in minimizing complications, such as pneumothorax, and in enhancing overall patient and inserter insertion safety. The introduction of the MTFPICC as an alternative access site for patients with central vessel occlusions highlights the program's adaptability and commitment to patient-centered vascular access care. This innovation not only addressed the specific needs of a complex patient case but also demonstrated the VAT's ability to collaborate effectively with physicians and other healthcare professionals in making informed decisions that prioritize patient safety and procedural quality.

Despite the program's success, there are areas that warrant further exploration. Expanding the scope of the NDCLI program to include other vascular access devices, such as temporary dialysis catheters, tunneled catheters, and bedside port placements, could further enhance the role of nurses in vascular access. Additionally, the long-term impact of the NDCLI program on healthcare costs, patient length of stay, and overall resource utilization should be investigated to provide a more comprehensive understanding of its benefits.

Conclusions

This 4-year follow-up highlights the significant impact of NDCLI programs on insertion success and low insertion complications. By empowering nurses to lead the insertion and management of CVC and AC, the NDCLI model not only enhances the efficiency and standardization of care but also demonstrates the value of expanding the scope of nursing practice in vascular access.

The insertion success rates and low insertion complication rates observed in this follow-up highlight the importance of nurse-led initiatives. Further follow-up and research are essential to evaluate the long-term outcomes of NDCLP Continued analysis will help identify trends, refine best practices, and ensure sustained improvements in patient outcomes and care quality.

As healthcare continues to evolve and patients become more complex, clinicians must adapt. NDCLI programs serve as a powerful example of how leveraging the expertise and skills of specialty nurses can drive positive change in patient care, much like other nurse specialists such as infection pre-ventionist (IP) and wound care nurses (WCN). The progression of these programs to include other vascular access devices and sites should be explored further to continue advancing the role of nurses in this critical area of healthcare.