More than 300 million peripheral intravenous (PIV) catheters are used annually in the United States to provide life-saving treatments for patients.1 More than 80% of admitted pediatric patients will require placement of a PIV catheter to complete medical treatments or therapies during their hospital stay.2 Given the scope of PIV use in hospitalized patients, finding ways to maximize first-time PIV placement success is integral in today's health care landscape.

The pediatric inpatient population brings unique challenges to health care professionals when attempting successful PIV access. Patient size, age, disease process, vessel integrity, history of peripheral access, and patient experiences can all influence a nurse's success.3 Adding to the fundamental challenges that a pediatric patient's anatomy and physiology place on the nurse, PIV placement is one of the most commonly reported painful experiences that pediatric inpatients report.4 Studies have shown that first-attempt success rate of placing a pediatric PIV ranges from to 24% to 52%,2‘5‘6 with an average of 2.2 attempts.3‘7 Other key factors affecting the nurse's ability for first-attempt success include the pediatric patient's ability to cooperate along with parental perceptions of the nurse's ability to perform the procedure.7

Multiple failures for PIV placement affect rising costs for health care institutions. The median direct cost of placing a PIV on an inpatient with 1 to 2 attempts is $41, whereas the cost can rise to more than $125 for patients who had more than 2 attempts.8 Additional PIV failures can lead to further system resource use by contributing to delays in medical care, potentially prolonging hospitalization and patient bed-days.8 When there is a need for increased resources such as pain management and Child Life services, the costs can continue to rise dramatically.

Lack of successful PIV placement causes increased stress, anxiety, and fear for the patient and caregivers, which can then decrease a nurse's confidence in skill performance.9 Multiple failed PIV attempts may also lead to complications such as phlebitis and hematomas.10 The experience of multiple failed attempts and poor outcomes can have long-lasting effects over a patient's lifespan and affect future health care choices, including chronic trypanophobia.7,11 Due to medical advancements, children with chronic or life-limiting conditions such as cystic fibrosis and congenital heart conditions have seen increases in prognosis and life expectancy. Careful attention needs to be paid to promoting the vascular integrity to support the pediatric patient into adulthood.

DIVA scoring tools

The DIVA 4 original scoring tool was developed as a predictive tool to guide clinicians whose pediatric patients were at the highest risk for difficult intravenous access.12 The DIVA 4 evaluated 4 factors: history of prematurity, age, vein visibility, and vein palpability. As part of this original work, Yen and colleagues12 also evaluated a proposed DIVA 5 tool which included an additional variable (skin shade) but did not ultimately find the inclusion of this variable to be statistically significant. Additionally, there are 2 other validated models (DIVA 3 and DIVA 4a) that were validated in the pediatric emergency department (ED) setting, which include patient age, vein visibility, and vein palpability.13 DIVA 4a also includes the addition of an admission history to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)12‘14(Table 1). A total score of 4 or more in any DIVA model implies a 50% increase in a first-attempt PIV failure. A high DIVA score allows the clinician to anticipate difficulty in obtaining peripheral vascular access and obtain additional resources prior to attempting placement in order to improve the chance of first-time success. Resources may include the use of a specialized pediatric vascular access team (VAT), use of visualization technology such as transillumination (shining a bright light through the skin), infrared technology, or ultrasound-guided placement.

Table 1. DIVA scoring toolsa

| Vein visible (Y=0; N=2) | Vein palpable (Y=0; N=2) | Age (<11 mo=3; 12-35 mo=1; ≥36 mo=0) | History of prematurity (Y=3; N=0) | History of NICU Admission (Y=3; N=0) | Skin shade (light=0; dark=1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIVA 314 | X | X | X | |||

| DIVA 4 original scoring tool12 | X | X | x | X | ||

| DIVA 4a14 | X | X | X | X | ||

| DIVA DO512 | X | X | X |

DIVA=difficult intravenous access; N=no; NICU=neonatal intensive care unit; Y=yes

a Table outlines the criteria included in each DIVA scoring method. The weights of each metric are displayed in the column header. The metrics used to calculate each DIVA score are denoted by an X in the respective columns

DIVA score's relationship to success for PIV placement

The DIVA scoring tools have been successfully established as a predictive tool to guide clinicians on establishing the timely placement of a PIV catheter. Evidence in the use of this tool has demonstrated that a score of 4 or greater assisted in identifying patients at a 50% to 60% risk for first-attempt failure in the pediatric ED setting.14‘15 The total score can also anticipate the need for additional interventions for establishing PIV access for the medical management in the pediatric emergency population.10

Application to the inpatient pediatric population

While there is supporting evidence for the effectiveness of using the DIVA scoring tool in the pediatric ED, this predictive factor has not yet been replicated in the pediatric inpatient setting. In the pediatric ED, patients present with compromising physiologic conditions requiring immediate care including sepsis, trauma, and dehydration, all of which vastly affect blood vessel integrity and the ability to obtain access. The pediatric inpatient population have generally been stabilized and are less likely to have significant physiology affecting the vasculature unless there is a sudden deterioration in condition or known chronic conditions with a history of frequent hospitalizations.

Aim

The primary aim of this performance improvement project was to determine if the DIVA scoring tools are accurate in predicting the need for additional resources (eg, Child Life, topical lidocaine, warm packs, transilluminator, infrared technology, VAT) to secure a PIV on the first attempt in pediatric patients through 18 years of age hospitalized on a general care unit. The secondary aim was to compare the predictive value of the four currently established DIVA scoring tools among this inpatient pediatric population (DIVA 3, 4, 4a, and 5, respectively).

Methods

Setting

This performance improvement project with quality improvement elements was conducted at a medium-sized, 154-licensed bed tertiary children's hospital within a larger academic medical center in Rochester, NewYork. The project scope was focused on a 20-bed inpatient general care unit within the children's hospital. The children's hospital encompasses a level IV NICU and is a regional referral center for neonatology, with large volumes of discharged NICU patients in the community. The hospital employs a pediatricVAT, comprising3,6 full time equivalents. This allows for 12 hours of daytime coverage during weekdays, and 8 hours of weekend coverage. Members of VAT are also trained in the use of ultrasound technology to guide PIV placements. Pediatric patients who are subjectively deemed more difficult to obtain first-attempt success at PIV placement are typically referred to VAT.

Sample

A convenience sample of admitted pediatric patients through 18 years of age was used for this project. This method (as opposed to consecutive sampling) was chosen as data collection were at times limited by the availability and willingness of the nurse to complete the paper data collection tool. Data collection occurred over a 16-month time frame, from July 2018 through December 2019. Inclusion criteria were any pediatric patient admitted to the unit who required a PIV placed in a nonemergent setting. Any patient requiring emergent (within 1 hour) PIV access was excluded, as well as nurses who were still in their orientation phase and were therefore not deemed competent in PIV insertion.

Procedure

Nurses were asked to voluntarily complete a data collection sheet on each patient prior to attempting to obtain PIV access. All nurses off orientation and employed by the unit received PIV insertion training during their hospital orientation and were deemed competent to perform this procedure. No more than 2 attempts are recommended by any 1 nurse. Hospital guidelines recommend that a nurse with more advanced PIV skills should be consulted after 2 unsuccessful attempts. Training on completion of the data collection sheet was provided by project champions (members of VAT and senior unit-based nurse champion) using a train-the-trainer model. Nurses on the unit expressed excitement at participating in this project.

Permission from the author for use of the DIVA scoring tool was obtained electronically. Patient skin shade was assessed using the Fitzpatrick skin prototype, with the first 3 shades equaling light, and the last 3 shades equaling dark.16,11 History of NICU admission and the patient's gestational age in weeks was obtained from either the patient's family or from a manual chart review. After the nurse placed the tourniquet, the vein visibility and palpability were assessed. Documentation postprocedure included whether the PIV was obtained on first attempt, the total number of attempts needed (by all nurses), and other interventions used.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure of interest was to determine if each DIVA scoring tool is accurate in predicting the need for additional resources to secure a PIV on the first attempt. The secondary outcome measure of interest was to compare the predictive value of each DIVA scoring tools among an inpatient pediatric population.

Analysis

Prior to analysis, data exploration and cleaning were performed. This process included assessing for missing data, reviewing the data profile, correcting values as needed, and calculating necessary columns. Following data evaluation and cleaning, a correlation analysis was performed. The logistic regression assessed DIVA score effectiveness to predict success of PIV insertion on the first attempt.

The data evaluation and cleaning included reviewing records with missing values, which were omitted unless they could be inferred from available data (n=17). They were omitted if they did not have one of the elements needed for any of the DIVA scoring methods. Only records that could have all 4 DIVA scores calculated were used for this analysis. This was done so that each score was comparable to underlying data.

The missing DIVA scoring elements were then calculated. All DIVA scoring columns were inspected to make sure every value fell within the expected range of the score. Incorrect values were fixed if possible, using the underlying data. Each DIVA score was calculated individually so that the scoring method could be evaluated separately. The cleaned data were then used in further analysis. The primary outcome of interest of PIV success on first attempt was converted to a numeric format for logistic regression.

A correlation analysis was performed to further explore the data. Following standard correlation calculation and matrix building, a logistic regression model was created. A binary logistic regression for first-attempt PIV success was chosen to evaluate the primary outcome of interest. This method allows for each record in the data to be assigned a classification (first-attempt success or failure) using the variables of each DIVA scoring method. The resulting classification can then be compared to the actual result to determine how well the DIVA scoring methods performed at predicting first-attempt PIV success. Scikit-learn was used for model development.18 The response variables were coded as 1 (first attempt) and 0 (required more than 1 attempt).

A separate model for each DIVA score (DIVA 3, 4, 4a, and 5) was then trained. The columns corresponding to each DIVA scoring method were used as inputs for each model. In order to assess model performance, the data were split into training and testing sets (80% training, 20% testing). Trained models were then deployed on the testing data. Then 1000 randomly sampled iterations were used for each logistic regression model.

Ethical considerations

The proposal and manuscript were peer-reviewed by the University of Rochester Medical Center's Evidence-Based Practice and Research Committee and deemed to be exempt from research. This project was considered performance improvement to assess feasibility of using the risk assessment tool among pediatric hospitalized patients and did not require Institutional Review Board approval.

Results

DIVA scores

All DIVA scores (3, 4, 4a, 5) were calculated for each patient included in the data set. The criteria for each DIVA scoring method are displayed in Table 1. All DIVA scores are calculated on a 0 to 10 scale. Each metric carries a numerical value, and they are summed to calculate a DIVA score. The metrics have a yes or no response with yes equaling 0 and no ranging from 1 to 3, depending on the variable. The exception to this is skin shade, which is 0 for light and 1 for dark. The value for each metric can be found in Table 1. Of133 unique individual pediatric patients enrolled in this project, 167 PIV attempts were recorded. After data evaluation and cleaning, 150 PIV attempts were included in the final analysis. The overall success rate of placing a PIV on the first attempt was 60% (n=90). The most common reasons for hospitalizations included postorthopedic procedures (n=33), respiratory disturbance including asthma, pneumonia, and respiratory syncytial virus (n=23), cystic fibrosis (n=15), and eating disorders (n=12).

A power calculation was done following data collection to determine what sample size would be needed. This was done using the high and low end of the first-time PIV success rate from the literature. With a 23% success rate would require a sample size of approximately 270, and a 53% success rate would require a sample size of approximately 380. This is for a 95% confidence interval and 5% error.

Age

The average age was 9.1 ± 6.0 (0-18) years old. The sample size was insufficient to stratify by age.

NICU admission or prematurity

In this sample, 12% (n=19) of patients were born prematurely, and 20% (n=30) of patients had a history of a NICU admission, with a mean gestational age of 37 weeks ± 4.4 days.

Skin shade

Persons of color comprised 14.7% (n=19) of the total sample population, based on race and ethnicity documented in the electronic medical record. The majority of the children were assessed to have light skin (n=128, 85.3%).

Vein visible or palpable

In 57.3% (n=86) of PIV attempts, the vein was visible, and in 60.7% (n=91) of PIV attempts the vein was palpable.

Variable correlation matrix

Following data preparation and DIVA score calculations, a correlation analysis was conducted using all variables in order to assess the relationship between each variable. A correlation matrix was created as a result, which can be obtained from the authors on request (Rebecca_Kanaley@urmc.rochester.edu). A strong correlation was found between each DIVA score and their respective components. A weak negative correlation was identified between first-attempt success and the 4 DIVA scoring methods. This suggests a weak relationship between higher DIVA scores and an unsuccessful first PIV attempt.

Logistic regression

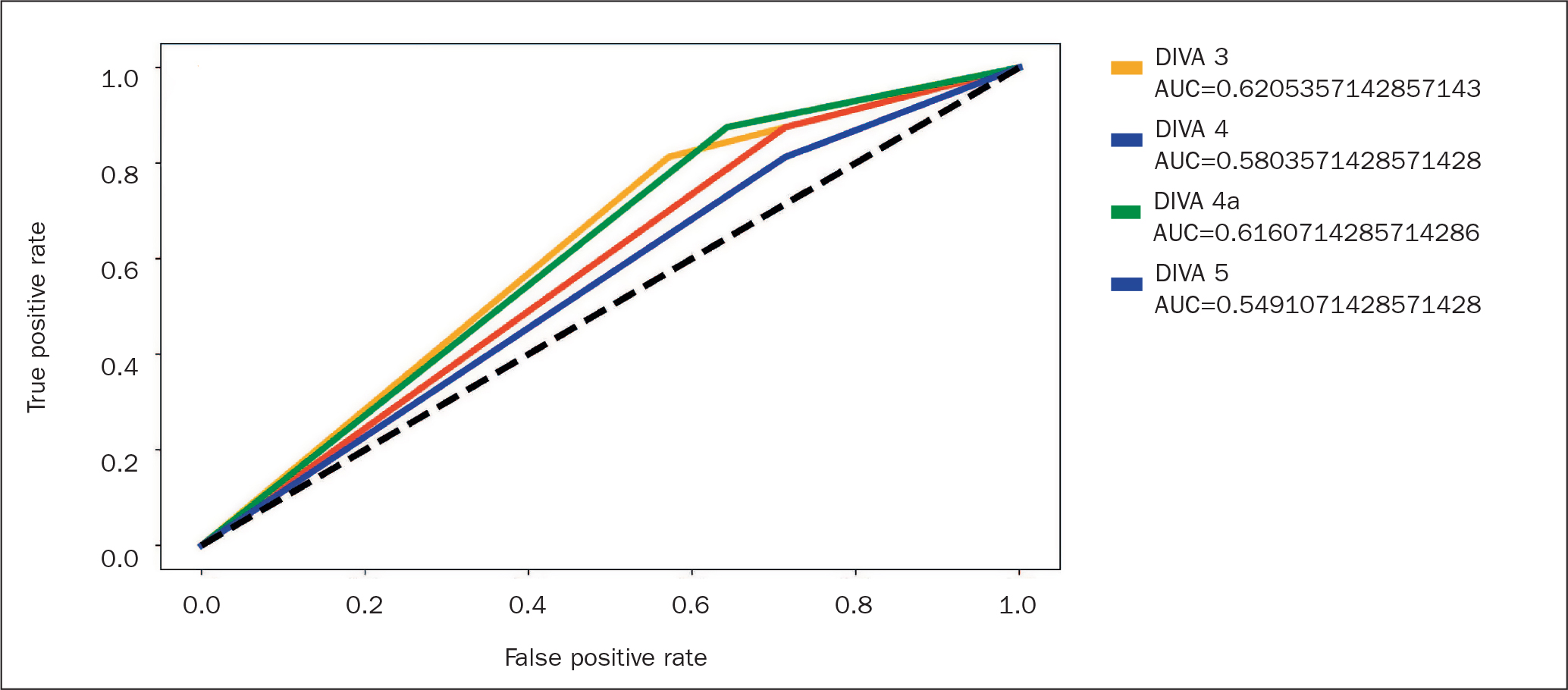

The effectiveness of each DIVA scoring method was evaluated using a logistic regression, which was run for each respective DIVA scoring method. The independent variables for each regression were the scoring metrics for each DIVA score (see Table 1). The resulting area under the curve for each metric is presented in Figure 1.

Performance was comparable across all scoring methodologies with the highest accuracy (0.620) being DIVA 3. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by running 1000 iterations of the data using an 80/20 training and testing split. The results are shown in Figure 2. The sensitivity analysis highlights the variability in the logistic regression results, likely because of the small sample size.

Discussion

DIVA models

In this project, the DIVA score alone was not a predictor of first-attempt PIV success. All 4 DIVA scoring modalities performed similarly. The highest average accuracy was 0.58 with DIVA 4a, which is only slightly higher than random chance. Vein visibility was the best individual predictor across all DIVA scoring methods, although this was not: statistically significant (P=0. 212).

Age

This sample included patients through 18 years of age. This decision was made to include older pediatric patients as it is more reflective of the general pediatric inpatient population and therefore the results are; more generalizable.

NICU admission or prematurity

There was a relatively smali sample of patients with a history of N)CU admission or prematurity. This wts consistent with previously published limitations during the DIVA validation.14 Because of the local community demographics consistent with having a regional referral center for neonatology with more than 1200 annual average NICU admissions, more patients meeting this criteria had been anticipated for this project. As children age into adolescents, their history of prematurity may play less of a factor in vascular access. Neurodevelopmental disabilities are more prevalent in the extremely preterm population,19 however medical complications that impact PIV access and effects may lessen as the child's veins grow and develop. Similar reports on prematurity's effects on the vasculature suggest that this risk factor normalizes after the age of 4 years.20

Vein visible or palpable

The factor of·vein palpability had the strongest correlation for fiest-time PIV success, but overall is was a weak predictor (0.21). Many nurses, especially nurses with less clinical experience, rely on visual confirmation of the vessel for successful PIV placement. Without this visual confirmation, a newer nurse may be more likely to struggle when placing a PIV catheter.

Sekin shade

The assessed skin shade dici not have a strong correlation with first-time PIV access (0.085). Skin shade contributes to the overall vein visibility - the darker the skin shade, the less likely that the vein will be visible without assistive technology. Anecdotally, some of the newer nurses in this institution have expressed hesitancy in attempting PIV. placement in darker-skinned children given their physiological difference in vein visibility. This may have introduced selection bias into this sample as children with darker skin (identified via the Fitzpatrick skin prototype) may have been referred to VAT for an initial attempt at a PIV placement, thereby excluding them from this performance improvement project.

PIV success is multifactorial. A high skill level is needed for successful placement of a PIV in pediatric patients.3 None of the nursing schools in the region teach PIV placement as part of their programs; all of the newly graduated nurses are novices with this complex yet common nursing skill. Years of experience in health care has shown to increase success rate with PIVs, suggesting it may take up to 5 years to obtain full competency.1 Further data analysis will explore the relationship between nursing experience level and confidence with PIV placement in this patient population.

Careful consideration to the overall physical assessment and patient condition is crucial for PIV success. Children who present initially to the ED are generally experiencing an acute illness or injury, which could negatively affect their vasculature's appearance. Once stabilized and admitted to a general inpatient pediatric unit, the child has returned to a more normalized hemodynamic state and has improved vascular access options. Certain patients with complex and chronic medical conditions that lead to frequent hospitalization often bypass the pediatric ED and are admitted directly to the inpatient unit. Having scoring tools that encompass this population is key to generalizing results to all pediatric populations. This project excluded pediatric inpatients who needed urgent vascular access (within 1 hour) as their vasculature may likely be more similar to those seen in the pediatric ED.

The DIVA score has been validated in the pediatric ED setting, and recent research has begun to explore its applicability to other patient populations. In one recent publication, authors suggested that a high DIVA score of >4 was an independent predictor when applied in the pediatric operating room.2 Other additional factors that influenced multiple attempts for a successful PIV insertion included presence of a chronic disease and body mass index outside of the normal range.20,22

Limitations

A limitation of the project was the use of convenience versus consecutive sampling. Convenience sampling was chosen because of the voluntary nature of staff completing the data collection form prior to participation. This form was in-depth and required obtaining information from multiple data sources, which may have affected the nurses’ ability to complete it given time constraints. The sample size therefore did not include every PIV that was inserted during the project, and sampling bias may have occurred.

Because of small sample size in this small, single center location, there was great chance of model variability, and our statistical power was limited. In particular, statistical power was not reached among pediatric patients with either a history of prematurity or history of NICU admission. Our pilot unit is the preferred location for admissions from Adolescent Medicine Division and Pediatric Orthopedics. We hypothesize that this patient population may have affected the overall patient characteristics in this sample.

A small sample of children assessed with dark skin was observed in this project (n=28). In our project, dark skin was associated with a 50% chance of first-time PIV failure. The small sample size did not provide adequate statistical power and does not allow us to draw any conclusions as a predictive factor. Although this is not statistically significant, it has clinical significance of failing to obtain PIV access on the first attempt almost half of the time in this patient population. This racial disparity among children with darker skin color needs to be recognized and has been noted in previous studies.3

The sample population also had little ethnic diversity, with only 5.7% identifying as Hispanic/Latino (n=9). Non-Hispanic/Latino represented 80.5% of our sample population (n=128). Future efforts should be aimed to address the health care disparity and exploring additional mitigation resources, with attention applied during quality improvement efforts to ensure diversity is evaluated.

Conclusions

None of the 4 DIVA scoring models predicted first-time success for PIV placement among hospitalized children. Additional efforts should enroll a larger sample size with racial diversity and continue involvement of statistical experts. The DIVA scoring tools do provide some standard definitions to PIV insertion that can be further studied and adapted for pediatric inpatients.

Recommendations for practice

While DIVA provides nurses with a tool to predict likelihood of obtaining PIV access on the first attempt in the pediatric ED, no single predictive tool alone replaces expert clinical decision making (assessment at the time the patient needs vascular access) when choosing the right device, irrespective of the patient care setting. Predictive tools such as DIVA are intended to assist the nurse, not completely replace the nurse's clinical expertise. It is critical to have the appropriate resources available to nurses, such as visualization technology and specialized services, so nurses can be empowered to make the best choice when obtaining vascular access for children.