A collaborative project to support evidence-based practice and continuous quality improvement (QI) was undertaken by six service provider organizations (SPOs). These SPOs are members of the Ontario Provincial Nursing Practice Council (NPC) and the Provincial Clinical Practice Subcommittee (CPS), a branch of the NPC. The CPS undertook this QI work with the goal of standardizing the process of administering a first dose of a parenteral medication in the community setting.

A three-year project ensued, resulting in the development of guiding documents, including a standardized first-dose patient eligibility screener, patient and nurse education material, and a competency checklist to assess nurses' proficiency.

Purpose

Problem statement

The lack of standardized processes for administering the first dose of a parenteral medication in the community impacts patient care and results in delays in treatment, increased emergency department (ED) visits, and SPO operational challenges, resulting in a poor patient experience and negative healthcare outcomes.

Background

Home infusion therapy can be safe and effective, improve patients' quality of life, and reduce healthcare costs (Gorski, 2020; Gorski et al, 2021). It has been identified that home infusion patients were no more likely to experience adverse reactions (Polinski et al, 2017), and one study identified that 95% of patients completed home infusion safely and experienced no adverse reactions (Viteri, 2023). Administering a medication intravenously for the first dose requires careful consideration, planning, and following best practice standards to ensure patient safety and efficacy; this includes having an established plan to respond to emergencies, such as anaphylactic reactions and ensuring clear communication between the patient and the healthcare team.

For more than 25 years, SPOs within Ontario have administered the first dose of parenteral medications. During the last five years, the home and community sector has seen an increase in the complexity of patients and infusates being prescribed and requested to be administered as first dose. Due to the increase and the desire to have consistent practice, it is necessary to use a standardized approach. With this need surfacing, a working group of volunteer clinical leaders from various SPOs was formed, which included clinical practice representatives from five SPOs, to explore this concern.

Administering the first dose ofa parenteral medication within the community setting is a clinical practice that all nine of the SPOs deliver for select medications. When the first-dose process was reviewed, inconsistencies in practice among the nine SPOs were identified. For example, SPO A would administer a medication as a first dose while SPO B and C would not, creating confusion amongst frontline nurses, patients, and the provincial funder.

Members of the working group agreed that a standardized process would be the goal of this collaborative work.

The working group used the Canadian Vascular Access Association (CVAA) as the national guiding body for infusion therapy and vascular access care and management practice for nurses and other healthcare providers (HCPs).

The CVAA national guidelines define the recommended strategies and provide practice recommendations to all HCPs involved in the most common aspects of vascular access and infusion therapy (CVAA, 2019).

The CVAA mission statement provided the foundation required for this work — “CVAA will advocate for safe quality care across the healthcare continuum by providing leadership and empowering/engaging its members and the broader healthcare community to promote education, partnerships, knowledge, and research in vascular access and infusion therapy for optimal patient outcomes” (CVAA, 2019, p.6).

The aim of this QI work was to standardize the practice and minimize the variation of clinical practice, to achieve positive outcomes for patients (CVAA, 2019).

Method

How we approached the challenge

The working group began this collaborative effort by reviewing the eligibility criteria of a parenteral medication to determine suitability for receiving its first dose in the home, and by reviewing recorded risk (allergic reactions) from the participating SPOs and the provincial government funder.

It was noted that the screening criteria differed among the SPOs and funders, and different geographical areas were serviced by different teams utilizing different versions of the first-dose screener. Our review highlighted gaps in standardization.

Our preliminary work involved reviewing all first-dose screeners from the SPOs and the provincial funder and reviewing and identifying consistencies and differences (see Appendix A, online). An initial inconsistency discovered was the definition of ‘first dose.’ This varied from patient has not received the medication within 30 days to patient has never received the medication in the past. There were also differences within the length of time to have a nurse remain with the patient postinfusion and the age of the individual who can remain with the patient. Another major discrepancy discovered was the list of medications considered safe for a first-dose administration in the home and community, and medications that would never be administered as a first dose in the home and community.

Evaluation of the literature

Based on the nature of the QI work, a literature search was completed using Medline, PubMed, and Google Scholar to determine current state and evidence-based practice when administering a first dose of a parenteral medication and risk for anaphylaxis. There was a surprisingly low number of studies and articles identified that discussed the process of administering a first dose of a parenteral medication within the home and community sector. Key words used to conduct the literature search included parenteral first dose, initial dose, anaphylaxis, pharmacology, pharmaceutical, drug*, “intravenous”, “IV”, “infusion”, “antibiotic”, “antibacterial”, “anti-infective”, “allergy”, “anaphylaxis”, “side-effect”, “adverse effect”, “hypersensitivity”, and permutations. There was also an exercise in cross-referencing the risk with all the medications included on each of the SPOs lists.

While performing the initial literature review in 2021, the working group identified that the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) standards of practice (Gorski et al, 2021) included guidance surrounding the screening of patients and administration of a first dose of a parenteral medication in home care in its 2021 standards of practice (Gorski et al, 2021). The INS continues to provide first-dose-in-home-care guidance in their 2024 standards of practice (Nickel et al, 2024). The working group searched for Canadian guidance to be able to provide a Canadian context and support this work within the Ontario healthcare system. The working group looked to the CVAA 2019 Guidelines for the first dose of a parenteral medication; unfortunately, nothing specific was noted.

The clinical leaders wanted to define first dose clearly. We also reviewed the why behind our various first-dose screener questions. It was determined that some of the specific SPO screener questions were added based on historical events, i.e., a time when administering the first dose within the home and community did not exist. There was little to no evidence on which to base practice over the last 25 years when the community first started being asked to administer the first dose of a parenteral medication.

Working together

With the discrepancies identified and the literature search completed, the working group met regularly over several months to work through the differences in the individual SPO parenteral first-dose screeners. The goal was to create an aligned screener that was based on best practice and up-to-date scientific research (evidence; see Table 1). This collaborative effort resulted in creating a unified approach to first dose within this sector.

| Criteria | Changes to first dose of a parenteral medication screener |

|---|---|

| Medications not appropriate for first dose in home/community | Streamlined to only 10 medication categories |

| Age criteria | No longer defined; aligns with the infusion Nurses Society (INS) standards (Gorski et al, 2021) - alert, cooperative, and able to report body symptoms |

| First-dose time factors and definitions | Defined first dose as initial dose of medication by parenteral route (never received before; Jones, 2015) |

| Post-administration observation period by family/caregiver | 4 hours by a responsible adult - longer if indicated by product monograph |

| Safe transportation home | Patients must have arrangements with a responsible adult for safe transportation home from clinic postadministration |

Development of first dose resources

An important aspect of the QI work was the development of resources to help support the screening of patients to determine eligibility and identify potential risks of which a nurse needs to be aware. In the end, a standardized First Parenteral Dose Screener, patient education, nurse education, and evaluation metrics were created.

Standardized First Parenteral Dose Screener

The first dose screening tool is critical to identifying patients who are eligible to receive first dose administration based on select criteria of medication type, age, definition of first dose, observation period, and patient transportation after first-dose infusion.

The screener

Table 1 highlights the criteria and changes incorporated into the first-dose screener.

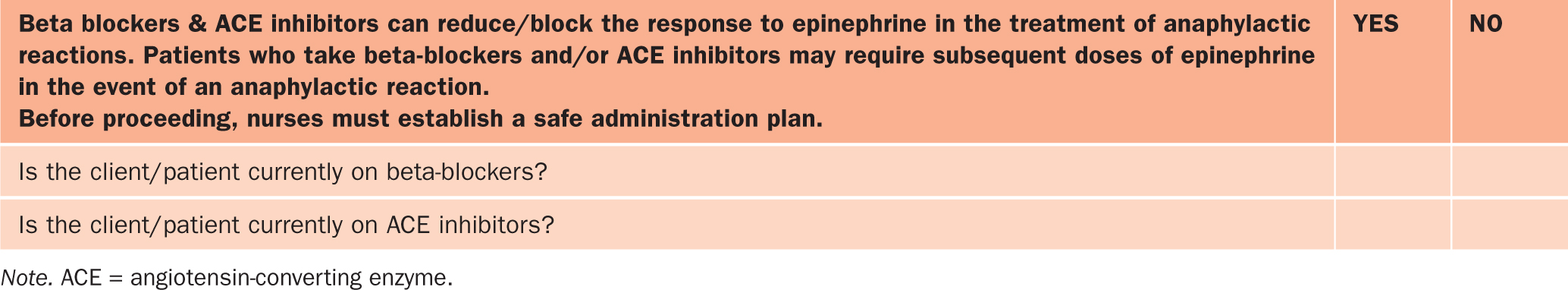

A significant discussion point of the criteria was the interaction between epinephrine (a rescue medication to respond to an anaphylactic reaction) and beta blockers and/or ACE (angiotensin-converting-enzyme) inhibitors.

The question examined whether epinephrine would be effective if a patient was taking a beta blocker or ACE inhibitor. Research demonstrates that anaphylactic reactions can occur at any time (Canadian Pediatric Society, 2018; Cardona et al, 2020; Norris et al, 2019). The focus should be on nurse and patient education and how to respond to any type of reaction at any time, as reactions can occur later in their treatment program. Traditionally, patients who were taking beta blockers or ACE inhibitors were excluded from receiving their first dose at home or in the community, as these medications are known to impede the effects of the hormone epinephrine. The working group identified that a risk benefit analysis needs to be performed for every patient to identify risks and communicate these to the care team and the patient and/or family. Patients taking beta blockers and/or ACE inhibitors are no longer excluded from receiving the first dose at home or in the community. This was a significant change in practice for the home and community sector (see Figure 1).

Change management and supporting critical thinking about when and when not to accept the referral for the first dose if a patient is on these drugs was a key part of our implementation plan for community nurses who were accustomed to refusing patients taking beta blockers or ACE inhibitors.

Patient teaching handout

The team determined patient education was a key component when administering a new medication in the community setting. The working group collaborated to create a patient and family education handout (see Appendix B, online), which nurses provide to each patient. The nurse reviews the content in the handout with their patients and/or families on how to respond if there is a reaction after the dose of the medication has been administered when the nurse is not present. The patient education handout is customizable for each SPO to personalize the tool to meet their needs.

The working group determined that nurse education was critical to ensure nurses are knowledgeable and competent to administer the first dose, based on the most recent research on first-dose and anaphylaxis risk. The working group developed curriculum to support nurse education, which included the definition of first dose, how to perform a risk benefit analysis, how to complete the updated screener, and the importance of patient and family teaching about anaphylaxis, that each SPO would use to complete the education.

Frontline nurse competency development

Developing competence with the frontline nurse to administer the first dose of a parenteral medication was essential to ensure they had the knowledge, skill, ability, and confidence to administer the first dose, considering the important criteria and performance of the risk-benefit analysis that was required. To support this, curriculum was developed and incorporated into an education module.

Objectives of this education module were for home and community nurses to accurately define a first parenteral dose of medication and to give them the knowledge to prepare for and administer first dose in home and/or community setting safely.

Results

This QI work has been significant, seeing the length of time it took to research, develop, and implement the resources. To date, 100% (nine out nine) of the SPOs have participated in the process of implementing the screener. The evidence-based approach to administering the first dose of a parenteral medication is being utilized across the province of Ontario.

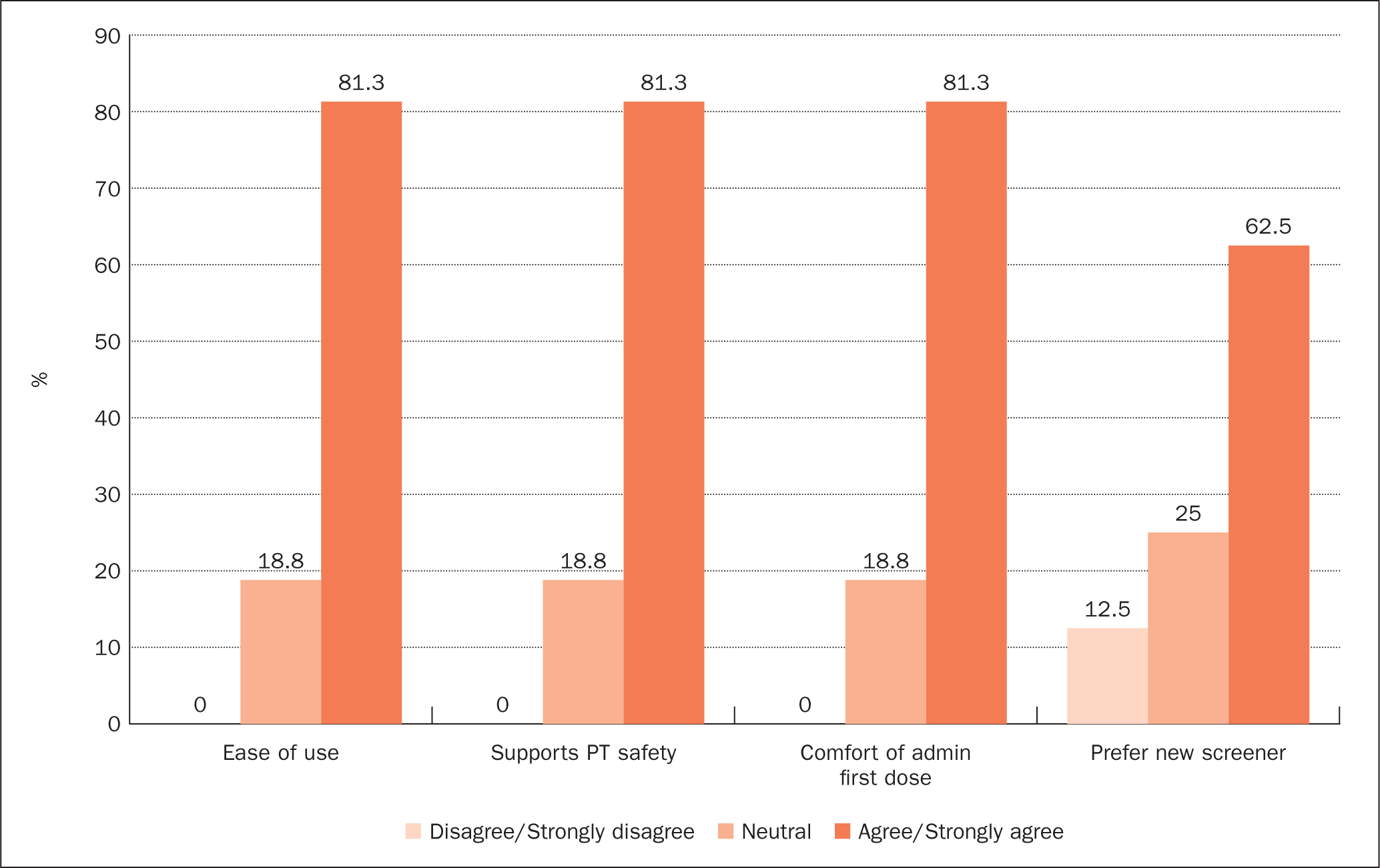

As part ofthis QI work, a survey was developed and conducted to identify satisfaction of nurses using the new screening tool. The survey looked at four elements: 1) nurse's ease of use of the new screener; 2) nurse's perspective on whether the screener and process supported patient safety; 3) nurse's comfort with administering the first dose; and 4) nurse's preference of using the new screener (see Figure 2). One SPO conducted the satisfaction survey with a plan for other SPOs to administer. The survey results showed a high level of satisfaction with the new screener.

Challenges

The ultimate goal of this project was to have all nine SPOs and the provincial funder in alignment with the first-dose process to ensure quality patient care. When we approached our funder to discuss the alignment of the evidence-based QI work, it was discovered that they were in the process of aligning their multiple screeners as well. At the time, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a need to move the administration of remdesivir to home and community rather than the acute care setting. Both groups agreed to work together to try to find alignment on a provincially unified first-dose screener. This involved several successful meetings with both groups, who aligned on several screening questions and the definition ofwhat a first dose is. Currently, SPOs are using a standard screener, and the working group is continuing to work collaboratively with our funder toward alignment in the first-dose process.

The other challenge discovered while working with SPOs with national coverage, and while presenting at the two CVAA conferences in 2023 and 2024, was that among provinces in Canada, differences exist in administering the first dose of parenteral medication. Some provinces, such as Ontario, have made great strides in moving forward with first doses in the community setting for most drugs that were deemed safe, whereas other provinces are still providing first doses in the acute care setting before the patient transitions into the community. The working group found this interesting and validated the need to advocate for the first dose of a parenteral medication to be included in the updated CVAA Guidelines.

Adopting the changes

Once the tools were developed, the work from the working group was brought back to the greater CPS for review.

Minor additional changes were considered and adopted. The working group shared these new tools and documents with all members of the CPS. Each SPO implemented these tools in their respective organizations and updated their policies, procedures, and education. The documents that the working group created were editable for organization-specific requirements, so each SPO may have had minor differences in the final first-dose screener, but the primary questions and drug lists were consistent.

Service provider organizations adopted the screener in different timelines, with most SPOs adopting it right away, but some opting to wait for alignment with the funder.

Disseminating findings

The working group showcased the preliminary work at the 2023 CVAA and World Congress onVascular Access (WoCoVa) joint conference and, within the presentation, advocated for the inclusion of guidelines for first dose of a parenteral medication into the currently being updated 2024 CVAA Vascular Access and Infusion Therapy Guidelines.

We also presented our updated work at the 2024 CVAA conference, where we shared utilization outcome data on how frontline nurses found the new tools. We were pleased to share feedback from our nurses who used the updated first-dose parenteral medication screener. Nurses found the new screener easy to use and preferred it to the previous screener. Nurses also stated that they found the additional education (both patient and nurse education) helpful and, after reviewing it, felt able to respond better to a reaction.

Quintuple Aim in supporting patient safety

The CPS' mandate is to explore priority practice issues and advocate for the use of evidence-based practice, ensure patient safety, and support equity. The working group opted to align with the principles of the Quintuple Aim (QA) to guide our project work. The QA provides a framework for advancing health care and addressing system-level challenges (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2024). The working group utilized the QA to explicitly design and guide the QI work to ensure that all five aims were taken into consideration when making changes to the first-dose process and the development of supporting documents: improved patient experience, improved population health, improved care team well-being, improved health equity, and reduced costs. Table 2 below outlines how the QA impacted the outcomes of each element.

| Aim | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Improved patient experience |

|

| Improved population health |

|

| Improved care team well-being |

|

| Improved health equity |

|

| Reduced costs |

|

Outcomes of first-dose work

To date, the QI work has accomplished a standardized approach across the province for administering the first dose ofa parenteral medication within the home and community care sector. Results of this work also provided advocacy for patients receiving a first dose ofparenteral medication in home and community care, to ensure those patients who want to receive the first dose at home and who meet the safety specifications can do so. The work also created system-wide efficiencies by increasing the acceptance of home care referrals to help support the capacity of acute care. Our final outcomes include the development of the First Dose of a Parenteral Medication Screener, nurse education, patient education, and a nurse competency checklist. By improving a nurse's competency in the first dose process (screening, administering first dose, and responding to complications that may occur), our hope is to increase patient safety (staying with patient and patient education).

Implications for future practice and next steps

The working group members will continue to collaborate with our government funder to identify gaps, focus on streamlining the first-dose acceptance process, and continue the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle and evaluation ofthe first-dose process by the SPOs within our CPS. A greater goal will be to advocate for clinical leaders in other provinces across the country to consider adopting a standardized practice of administering the first dose of a parenteral medication for all patients so prescribed. The CPS is willing to share this work with other provinces to support the first-dose project work in the home and community care sector. With the addition of and focus on the practice of administering a first dose of a parenteral medication in the updated CVAA Guidelines, leaders should feel supported to move forward with this patient-centred initiative.

The CPS has developed a QI process to evaluate the effectiveness of our work. We are currently working on developing tools to evaluate the following:

Positive change in patient care delivery

The following two patient examples highlight in practical terms the impact that the first dose work has had on patient care. By reviewing the first-dose process to be administered within home and community care, it has achieved the QI goals of decreasing delays in treatment, decreasing ED visits, and removing barriers SPO operational teams faced, resulting in improved patient experience and healthcare outcomes.

Patient experience example: John was taking oral antibiotics for an infection, but felt they were not helping him. His primary care practitioner decided to change the medication and route and has now prescribed him a stronger antibiotic to be administered intravenously. John has never had this antibiotic before. If this scenario happened in 2022, John would have been sent to the emergency department to receive his first dose, which may have resulted in a wait time of up to 12 hours and exposure to other patients in the waiting room, all while potentially spreading whatever infection he was fighting. Today, thanks to the collaborative efforts of our SPOs and funder, John can now receive his first dose in his home or an ambulatory clinic with a set appointment time.

Patient experience example: Harold, a 60-year-old male patient who had undergone a lung transplant, was diagnosed with COVID. He lives with his wife and two daughters.

Harold is taking a number of mediations: acetaminophen, carvedilol, clonazepam, ascorbic acid, duloxetine, eplerenone, furosemide, hydromorphone, magnesium oxide, metoclopramide, metolozone, rabeprazole, and remdesivir.

Harold's symptom onset of COVD started September 1.

By September 2 and 3, his COVID symptoms worsened.

A day later, he had a positive rapid antigen test (RAT), his fever broke, and he had become congested. September 5, Harold feels worse, experiencing a headache and cough. His vital signs include blood pressure 105/67 and apical pulse 88 (there was no thermometer in the home). His physician prescribed remdesivir. In 2022, Harold would have been referred to the ED for his first dose, where he would have encountered wait times, exposure to other illnesses, and potential spread of the COVID virus. However, after this QI work, in 2024, Harold can receive the first dose of remdesivir at home or in the ambulatory clinic, with no wait time and limited or controlled exposure potential.

Conclusion

This manuscript outlines a QI process, undertaken by a group of clinical leaders from competing home and community care organizations to standardize screening of patients for first-dose medication administration in the home and community care setting.

After several years of collaboration within our CPS, updated processes and resources have been developed and implemented to support administering the first dose of a parenteral medication in the home and community sector.

Aligned with the QA, this work has led to several accomplishments, including increased patient safety, diverting patients from the ED, consistent acceptance of referrals and delivery of care between SPOs, and a positive uptake from frontline nurses. Another unexpected benefit of this work was the development of well-established working relationships and collaboration among numerous SPOs, acute care sites, and the home and community care funder.

Finally, this group was able to share learnings and practice with the CVAA guideline committee and is very excited that CVAA's upcoming 2024 guidelines will include guidance on the first dose of a parenteral medication in the home and community setting.