Dementia is a global concern. It is estimated that more than 850 000 people in the UK are living with dementia, and this is expected to rise to above a million in 2021. People experience it in different ways, with a variety in severity of symptoms, which include short-term memory loss, difficulty retaining new information, increasing forgetfulness, impacted cognitive ability and communication problems (Dementia UK, 2021). Early diagnosis of dementia is often difficult, and people will often be classified as experiencing memory problems, rather than receiving a formal diagnosis of dementia (Alzheimer’s Society, 2021).

As a former community nurse, now with over 3 years of stoma care nurse (SCN) experience, the primary author (LC) together with the second author recognise that supporting patients with dementia is part of the daily care provided in the department in which they work. The increase in patients under their care being either diagnosed with dementia or experiencing memory problems has been noticeable. There has also been a concurrent increase in concerns raised by relatives about stoma care teaching, with patients occasionally denying having ever seen an SCN and also not being taught how to manage their stoma. This has made the role of the SCN more demanding, and potentially delays the discharge of patients from hospital to their homes. These aforementioned challenges highlighted a need in the authors’ department for a tool to enable timely interventions and give a visible, written knowledge base for family, carers and ward nursing staff.

The challenges

The management of the holistic needs of a patient with a stoma and dementia were identified as requiring an individualised and person-centred approach, due to the fact that dementia is a complex condition that affects every person differently. Being faced with the prospect of a stoma can be challenging for any patient; however, for a person with dementia, simply the experience of going to hospital can increase confusion and can upset and frighten patients (Black, 2011). A patient with dementia can:

- Experience a decline in cognitive function and difficulties in learning and retaining new information

- Find changes in environment confusing

- Have communication issues

- Experience a lack of continuity of care.

These factors can adversely affect the patient’s ability to achieve self-care in their stoma management, which is one of the most important aspects of the education provided by the SCN. It is a skill that requires repetitive teaching in order to be developed by the patient. Dementia and its associated symptoms, including a decline in cognitive function, make this more of a challenge (Powell, 2013). However, Dementia UK (2021) recognises that, despite this, it is important to promote independence through education to enable a patient to become self-sufficient in their stoma management. Dementia UK (2021) also recognises that this is not always possible in some cases and, therefore, a care package or placement in a care setting is sometimes inevitable.

The biggest challenge experienced by the authors’ team on the ward has been the lack of continuity of care during the absence of the SCN during evenings and weekends. Wards nurses will also ‘take over’ stoma management without necessarily involving the patient, family or carers, subsequently removing that continuity of care in their stoma management teaching.

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated many challenges for hospitals and nursing staff across the country, with many SCNs being transferred from their usual roles to work in other areas. The authors’ Trust continued to provide face-to-face pre-operative counselling for potential stoma patients. However, restrictions were placed on visitors to the wards, which meant carers and family members could not attend appointments or come in to observe pouch changes. Although the need to discharge patients as soon as possible after surgery remained, with increased urgency due to the status of some hospitals at this time. Fulham et al (2020) highlighted the need for nurses to work in different ways during the pandemic, incorporating the use of technology through virtual consultations and using SMS and email as alternative ways to communicate with patients and their relatives and carers. However, Fulham et al (2020) also highlight the fact that not all patients are able to use or access technology, and some face-to-face appointments needed to remain going forward.

To counter this, the patient progress diary, developed by the authors, remains a visual aid that the patient keeps possession of throughout their hospital stay and following discharge.

The role of the stoma care nurse

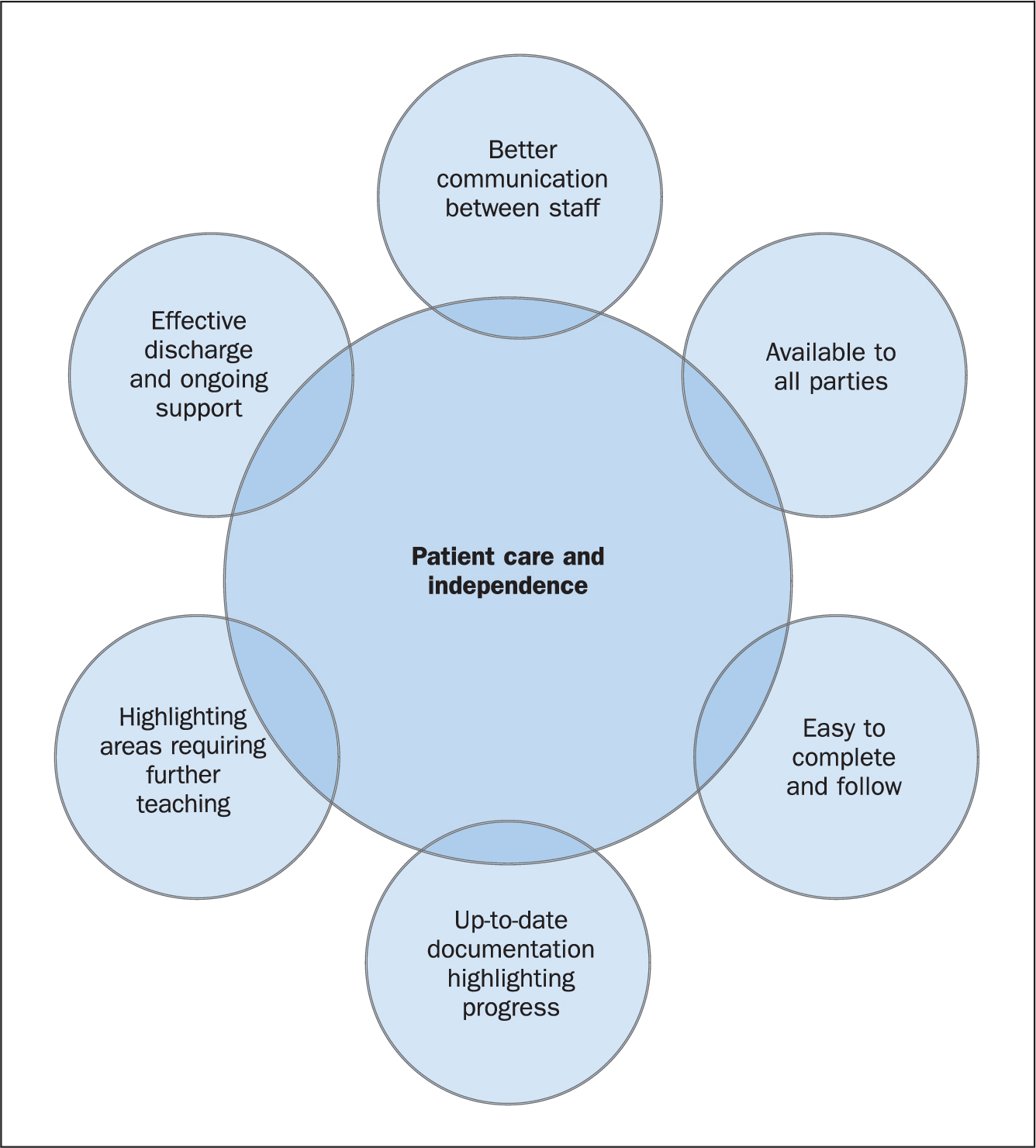

The management of long-term conditions can be challenging and difficult (Readding, 2016). It is the SCN’s role to assess a patient’s ability to become self-caring with their stoma. This process begins at the first meeting with the patient during pre-operative counselling, where barriers to this can be first identified (see Figure 1). It is usually through spending time and working closely with the patient and their family/carer that signs of memory problems and subsequent self-management concerns can arise (Colostomy UK, 2017), even in instances where a formal diagnosis has not been documented.

Discharge planning also starts at the initial pre-operative counselling meeting; therefore, this is a good time to discuss self-care and management of the stoma with the patient and their relative, who usually attends this appointment. The SCN assesses the patient’s ability to manage their stoma care independently and discusses the measures that can be put in place if the patient is unable to be self-caring with their stoma.

It is recognised that some nurses in acute care settings, despite local and national policies, find the teaching of stoma care challenging, and they are unable to adequately provide the care required to meet patient needs. Some research suggests that the needs of a patient with dementia can never be met, and a discharge into a residential care setting may be required (Fukuda et al, 2015). If it is felt that the patient requires more support, the SCN can signpost patients to Admiral nurses, who work alongside Dementia UK to support patients, families and carers in assisting individuals with dementia to return to their home environment (Swan, 2018).

The SCNs at Great Western Hospitals felt that the introduction of a patient progress diary to assist the SCN, ward nurses, family and carers, to make available an up-to-date and accurate account of the stage that the patient has reached in terms of independence in their stoma care, would enhance care and aid timely discharge. This diary was intended to supplement the work of the SCN, whose role is instrumental in enabling the patient to return to their previous level of independence.

The importance of improving care

The Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2020 report (2015) highlighted the growing global challenge of dementia, explaining that it is becoming one of the most important healthcare issues, due to its huge impact on people living with the condition, their carers and society (Department of Health and Social Care, 2015). The authors’ Trust policy, also highlights the importance of involving patients and relatives, ensuring that care is personalised, compassionate and choice-promoting. It emphasises the need for establishing the level of current and future multidisciplinary team (MDT) involvement, the importance of regular updates about discharge planning and early referrals for discharge planning.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) guidelines state that healthcare staff should identify the specific needs of people with dementia and their carers, taking into consideration factors relating to gender, sexuality, ethnicity, age and religion. Needs should be recorded and addressed. The Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK (ASCN UK) guidelines (2016) also acknowledge the importance of all patients being discharged from hospital with the skills and knowledge to be self-caring and reiterate that there should be a structure in place in cases where the patient lacks independence following surgery.

The discharge process needs to start early, with assessment of individual needs, and include a written care plan, which may require monitoring and adjusting. The Care Act 2014 recognises the importance of including the individual’s views, wishes, feelings and beliefs, alongside preventing or delaying the development of needs of care and support, which the Alzheimer’s Society (2021) supports, taking into consideration the patient and the person supporting their needs. To achieve this, there needs to be a system for monitoring and a plan agreed prior to discharge.

Introduction of the patient progress diary

The hospital policy and ASCN UK guidelines (2016) supported the need to develop a written teaching plan tailored to the patient’s needs. Therefore, the development of a diary to help achieve a more structured approach to care, with successful and timely discharge of patients with dementia, was launched.

The patient progress diary, which was developed from an idea raised during a Level 6 Advanced Management in Stoma Care course, is commenced at day 1 postoperatively and placed in the patient’s stoma equipment washbag. The key points are highlighted in Table 1 and show how the diary will benefit firstly, and most importantly, the patient, by providing basic questions, visual prompts, repetition and involvement. Benefits for the relative and carers include up-to-date feedback, identification of additional needs and accurate staging. Mendes (2018) highlighted the importance of involving carers, especially in the hospital setting, where their support is invaluable to improve patient outcomes. It also enables ward nursing staff to have up-to-date documentation that is easy to access and follow. The traffic light system incorporated into the diary (see Table 2) shows which stage the patient has reached with their care, with red meaning they need full support with care, amber that they require support and green that they are independent. This traffic light approach was developed initially by the authors’ Trust’s THINK initiative to promote timely referral to specialist nurse teams. This was produced in line with the THINK glucose initiative, which was produced by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2011). This format was also adapted to a patient format within stoma care in the authors’ department for the Stoma Care Assessment Guide (Hanley and Adams, 2015). This was designed to be an ‘at a glance’ tool that also assisted in providing patients with the correct care, in a timely manner, reducing hospital stay and delayed discharges.

Table 1. Key points of the progress diary

| Patient | Relatives and carers | Ward nursing staff |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Table 2. Sample page of the diary record

| Date | Requires support | Teaching | Self-caring | Other comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pouch emptying | ||||

| Pouch removal | ||||

| Cleaning and drying | ||||

| Applying new pouch |

The diary includes a tickbox table that is clear (see Table 2) and easy to read, and it can be accessed and used by anyone involved in the patient’s care. The format enables ward nursing staff to check which stage the patient has reached and provides the patient and their family/carers with a visual reference to their progress towards greater independence when the SCN is not available. For example, the patient may be able to remove the pouch and clean around the stoma, which would mean that they would place a tick in the green box for this category, but require support with pouch placement, requiring a tick in the amber box for this category.

Readding (2016) explained that multisensory teaching aids, allowing time, setting realistic targets and breaking down skills into stages can all help the patient gain confidence and new skills. Included in the preoperative pack provided by SCNs at the trust is a stoma trainer pack, so the patient can feel what it would be like to wear a pouch and practise changing one prior to surgery. The diary is introduced on the first day following surgery, along with a washbag that includes the equipment to manage stoma care. Willoughby and Fossett (2018) stated that educating a patient with dementia requires a person-centred approach, continuity, prompt cards, small tasks that are manageable, knowledge of the individual, patience and consistency. The patient progress diary assists in providing this by promoting practical solutions to health care. Strategies and techniques can be provided by the SCN in the comments box (Table 2) if the patient is struggling with a particular aspect of their care. The comments boxes can also be used to highlight adjustments in care. The diary helps to provide a clear, documented guide into how the patient learns and what stage they have reached.

Advantages of the patient diary

ASCN UK guidelines (2016) highlight the importance of discharge planning starting at the preoperative stage for elective patients or on admission for an emergency admission, so that any problems can be addressed at the start. This reinforces the need to introduce the patient progress diary early, in order to display accurate documentation of the patient’s progress in self-management of their stoma. The diary was introduced into the patient stoma kit washbag following an email to all ward nursing staff, and a copy of the diary was left in the staff room so that ward nursing staff could familiarise themselves with the format.

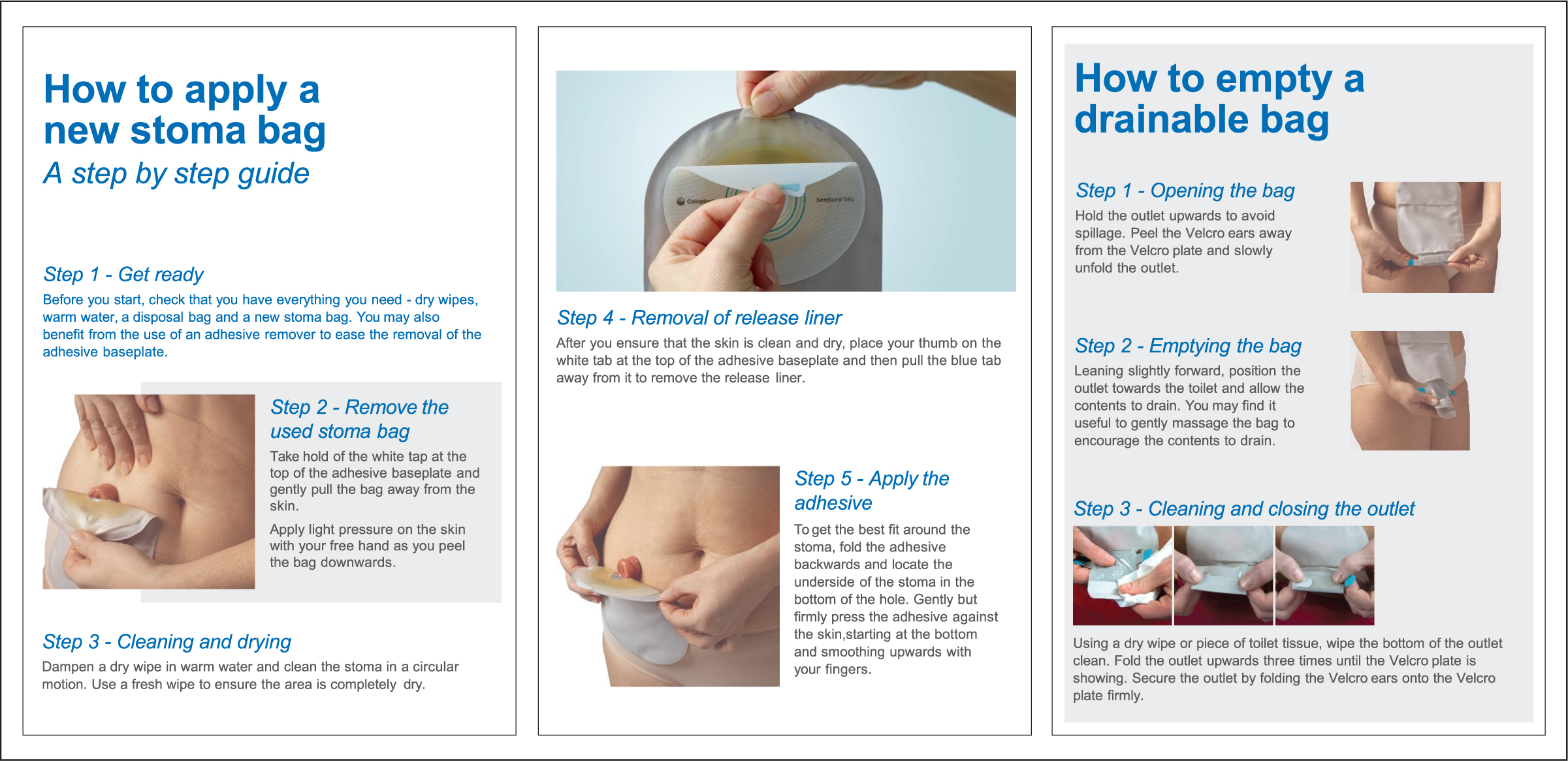

Education is also required to encourage ward nursing staff to promote patient independence because, in the absence of the SCN, they will often change the pouch for the patient, citing time or the patient’s lack of confidence. The introduction of the patient progress diary means that ward nursing staff and carers can check which stage the patient has reached and use the visual prompt of the step-by-step guide to promote participation in care. The diary is also taken home by patients, so that they and their family or carers can continue to use the step-by-step guide as a prompt.

Locally, we predominantly use a one-piece pouching system; however, the diary could be adapted to the use of a two-piece pouch change, if required. The diary includes a step-by-step pictorial and text guide to effective changing and emptying of a stoma bag (Figure 3).

Patients will often request that ward nursing staff change the pouch rather than do it themselves (Colostomy UK, 2017), and ward nursing staff are more likely to do this if they do not know what stage the patient has reached with stoma care. Black (2011) describes stoma management as a life-changing and disconcerting experience for everyone, but something that may be entirely impossible for someone with dementia. The patient progress diary combats this by providing an accurate account of the daily teaching of stoma management. The progress diary includes many box spaces for the SCN and ward nursing staff to record a patient’s competence level and progress with their care. To ensure that such an initiative is successful, the patient diary needs to be easily accessible to the right people, in the right place, at the right time (Walker and Manterfield, 2010).

Conclusion

Following positive feedback from the Patient Advice and Liaison Services and Carers Committee at the Trust, the patient progress diary has been used in the authors’ department since the end of 2019, with positive results. It has been introduced not only for patients with dementia, but for all patients with a stoma. The step-by-step guide that is part of the diary provides a visual prompt for the patient and all individuals and professionals involved in that patient’s care. The diary complies with local and national policies and guidelines to enhance patient care.

Since its introduction, the diary has received positive feedback from patients, as well as assisting with safe and effective discharges from the hospital setting. It also provides an opportunity for ongoing research and can be used as part of case studies for the management of patients who have memory problems or a diagnosis of dementia undergoing stoma formation surgery. As previously identified, the text and pictorial step-by-step guides can also be adapted for two-piece stoma appliances, and the authors welcome other SCNs using the diary.

KEY POINTS

- It is important to consider how stoma formation will specifically affect patients with dementia undergoing colorectal surgery and stoma formation

- A diary to improve the care of patients with dementia was developed following concerns about poor memory or retention of information by patients with dementia over their care

- A holistic, patient-centred diary was developed by the stoma care nurse team to improve the teaching of stoma care to patients taking into account local and national policies and guidelines

CPD reflective questions

- Why is it essential to ensure that patients with dementia receive timely, patient-centred interventions in order to facilitate an understanding of their stoma management needs?

- Consider a patient in your care who has dementia and describe how the use of the patient progress diary might have enhanced their experience following stoma surgery

- Discuss and compare the benefits of a patient progress diary with other patient-centred tools that you have used in your practice or are aware of