Older patients aged 65 years and above have the highest emergency department (ED) visit rate of all age groups, and this rate is increasing. For staff working in the EDs, frail older people present a significant clinical challenge. The atypical presentation of diseases, superimposed on complex medical and psychosocial comorbidities, creates demands on the ED system for which it was not designed. Accumulating evidence from Canada and elsewhere supports the efficacy of case-finding in the ED and linking frail seniors to services in the community. This evidence has been applied in the implementation of geriatric emergency management (GEM) in Ontario, a province in Canada (Regional Geriatric Program of Toronto (RGPT), 2024).

GEM programmes provide specialised frailty-focused nursing services to EDs; they were first set up in 2003. In recent years, several hospitals in Ontario have explored their value. The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care asked the RGPT in the early 2000s to place a GEM nurse in eight additional hospitals and evaluate their contribution to the health and wellbeing of older people. Seniors represent as many as 30% of the patients seen in EDs in Ontario, more than any other age group (RGPT, 2024). According to Statistics Canada (2015), on 1 July 2015, preliminary estimates indicated there were more people aged 65 years and above in Canada than children aged 0–14 years. Nearly one in six Canadians is at least 65 years old, equating to about 5780900 Canadians, compared with 5749400 children aged 0–14 years.

Illness complexity, hospital admission rates, lengths of stay and the risk of functional decline are also greatest for seniors. Indeed, ED visits are often sentinel events for seniors, carrying threats regarding loss of independence, health and wellbeing. The RGPT (2024) considers that decline and loss of independence can often be prevented or postponed through providing specialised frailty-friendly services in EDs.

GEM programmes have become a prominent initiative in Ontario. Currently, the GEM nursing network includes 103 nurses in 56 EDs across the province, who leverage their expertise to improve health outcomes for seniors who are frail or at risk of frailty. Led by advanced practice nurses with special training in working with older adults, GEM programmes provide recommendations for home support, follow-up with specialists and referral to the geriatric assessment outreach team as needed.

These programmes also play a crucial role in assessing seniors who may require additional care and support at home, with the aim of preventing repeat visits to the ED. A study by Ismail et al (2014) discussed innovative, high-quality services that help avoid unnecessary admissions, associated risks and costs among the geriatric population (defined as older adults aged 65 years and above). The innovation lies in involving a geriatric expert in providing early comprehensive geriatric assessment in consultation with the ED team, leading to promising patient outcomes.

Ismail et al's (2014) goal was to reduce unnecessary admissions by exploring alternative pathways where appropriate, such as intermediate care or early geriatric outpatient review. This approach aligns closely with the GEM nursing programme in Ontario, which aims to deliver targeted emergency geriatric assessment to frail seniors in the ED. The GEM programme seeks to help seniors access appropriate services and resources to enhance functional status, independence and quality of life.

Moreover, the GEM programme strives to establish geriatric and senior-friendly services in the hospital ED through collaboration, knowledge transfer and educational opportunities with other staff within various fields and departments.

Additionally, GEM programmes organise themselves to have strong networks and affiliations in the community, providing ongoing support for seniors after they leave the hospital and return home. The literature underscores the benefits of delivering multidimensional assessment and management through multidisciplinary specialist care teams for the geriatric population (British Geriatrics Society, 2017). The significance of a comprehensive geriatric assessment to identify the needs of older individuals is well documented, with comprehensive geriatric assessment often referred to as the ‘gold standard for the management of frailty in older people’ (British Geriatrics Society, 2017).

Although the success of GEM programmes is notable, particularly in Ontario, there is a clear gap in the literature concerning their cost-effectiveness or a cost-benefit analysis, especially when a service incorporates advanced wound care for geriatric patients visiting the ED.

According to Testa et al (2024), it is essential that future strategies for improving care in EDs align the needs of older adults with the overall purpose of the ED system. This alignment is necessary to ensure that improvement efforts are sustainable and that the ED functions effectively as an integrated part of the healthcare system.

Older people attending the ED include those requiring various types of advanced wound care, with wounds including but not limited to pressure ulcers (stage 3–4), soft-tissue infections, burns, lymphoedema and complicated and uncomplicated foot ulcers.

The objective of this study was to comprehensively assess GEM nursing and carry out a cost-benefit analysis of it, with a focus on expanding the scope of practice to include advanced wound care management for the geriatric population (aged ≥65 years) visiting the ED. The researcher evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of this initiative, considering its impact on patient flow in the ED and patient navigation, patient satisfaction and outcomes, as well as the self-actualisation of GEM nurses participating in the study.

Expanding GEM nursing scope of practice

The focus of GEM nursing is to identify potential geriatric syndromes in patients aged 65 years and over. These may encompass falls, incontinence, nutrition, constipation, pain, visual and hearing impairment, gait disturbances, mood/behavioural issues and other concerns. In 2015, the RGPT incorporated skin and wound health as one of the recognised geriatric syndromes (along with falls, malnutrition and functional decline, for example) (Testa et al, 2024), so it falls within the expertise of GEM nurses. However, limited attention has been given to this aspect in recent years. Currently, five acute care hospitals out of the 56 hospitals that participate in the GEM programme use GEM nurses for advanced wound management.

Needs assessment

Given the limited research on advanced wound care management in the ED, a needs assessment was conducted between November 2016 and December 2016 in two acute care hospitals in Toronto, Ontario.

The first hospital (hospital X) is a 272-bed academic health science centre. It offers a range of services, from emergency care to sophisticated brain surgery, and recorded approximately 67797 ED visits between 2015 and 2016. The ED staff includes nursing professionals, including advanced practice nurses – nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) who specialise in GEM and/or wound care – emergency physicians and allied health professionals (social workers, physiotherapists, physician assistants and occupational therapists).

The second hospital is a 190-bed teaching hospital (hospital Y) with an ED that attends to an average of 300 patients daily. Although its teams are comparable with those at hospital X, the GEM nurse at hospital Y is limited to geriatric emergency care. There is a recognised need for a CNS in wound and ostomy care in the ED at hospital Y.

The researcher conducted a survey involving 20 frontline clinical staff including the patient flow leader to gather their perspectives on the immediate wound care management by an advanced practice clinician in the EDs at both hospitals. The focus was on assessing the impact on patient flow and navigation, patient experience and clinician self-actualisation resulting from the expanded scope of practice.

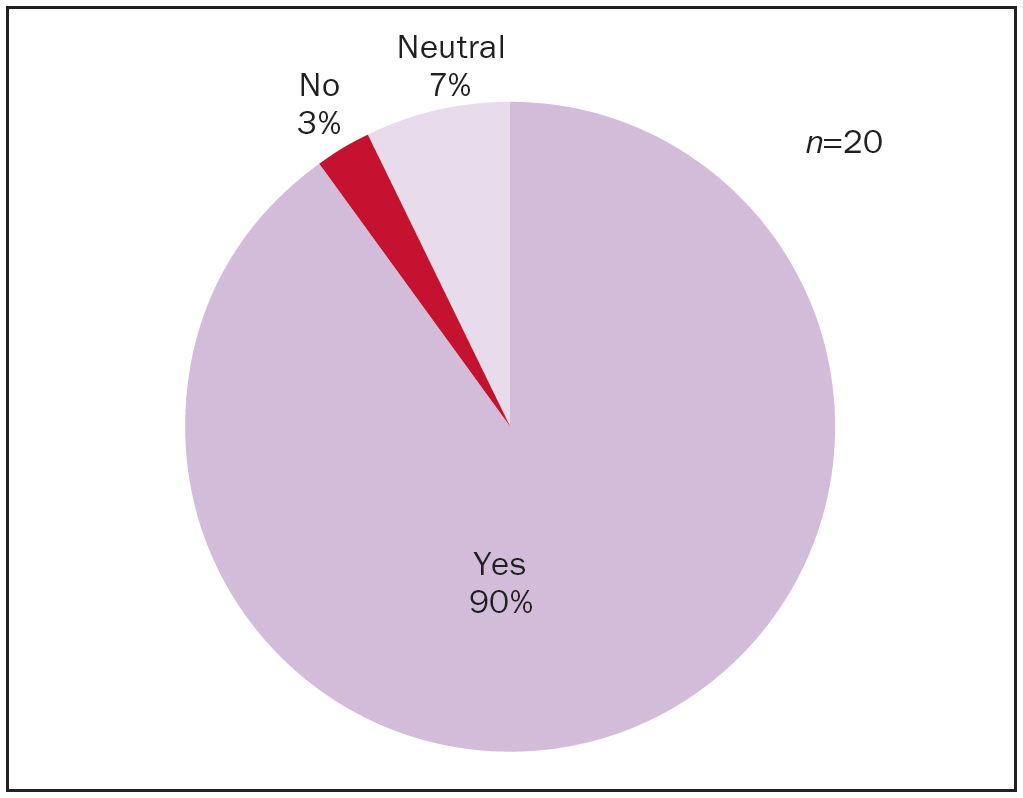

The survey results indicated that the majority (90%) of staff surveyed expressed a preference for a clinician dedicated to meeting the advanced wound care needs of ED patients (Figure 1). For clarity, the survey emphasised an expanded scope of practice for GEM nurses in providing advanced wound care management.

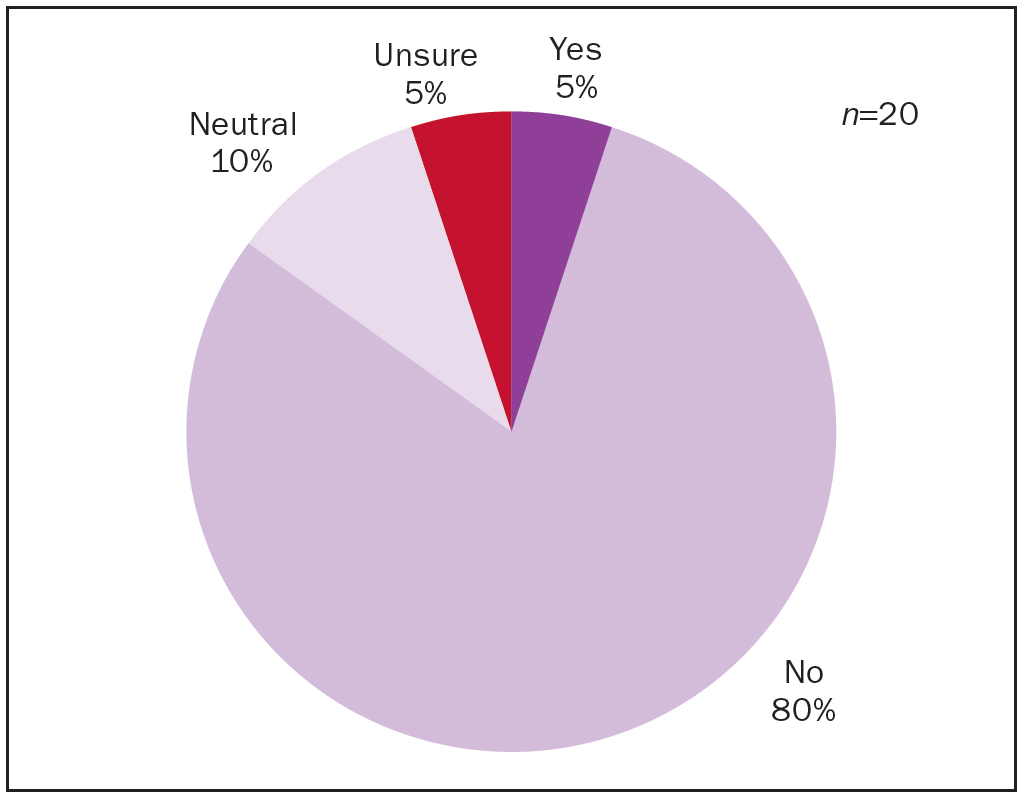

Simultaneously, another survey was conducted to assess the capability of frontline staff (including nurses, physiotherapists, social workers, occupational therapists, pharmacists and dietitians) to administer advanced management for commonly encountered wounds in the ED, such as pressure ulcers at all stages (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel et al, 2019), lymphoedema management. Only one of the 20 respondents indicated they were proficient in providing advanced wound care management (Figure 2).

Based on the findings of this needs assessment, it was proposed to expand the scope and responsibilities of a GEM nurse at hospital X. This particular GEM nurse is qualified to master's level and has extensive experience in his field. Holding national certifications in both geriatric nursing and psychiatric/mental health nursing, he has actively contributed to numerous quality improvement strategies related to ageing and older adults. Notably, he recently completed an advanced wound care certificate at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto, and achieved a master's level certification in wound care management in 2017.

Table 1 provides a summary of the goals and supporting evidence for this initiative.

| Goal | Resource | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 1. To deliver targeted, geriatric emergency wound care assessment and management to frail seniors in the emergency department | Collect quality improvement data that determine gaps and issues pertaining to assessment, management of wounds among geriatric patients | ✔ Evidence taken through quarterly audits of both geriatric emergency management and wound care consultations |

| 2. To improve patient flow by allowing patients aged ≥65 years to receive a faster wound care consultation if medically required, thereby enhancing their experience | Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario's best practice guidelines (2016), and related literature in skin and wound health | ✔ Improvement of patient flow in the emergency department as evidence by faster medical clearance for patient disposition |

| 3. To apply cost-saving measures based on the appropriateness of wound care products use by frontline staff | Evidence-based practices in effective wound care management that are appropriate in every wound care scenario | ✔ Reduction of unnecessary use of wound care products as evidenced by monthly wound care product audits by the medical device reprocessing department |

| 4. To create a comprehensive skin and wound consultation tool for patients needing advanced wound care management (eg stage 2–4 pressure injuries, peripheral vascular disease, complicated diabetic and non-diabetic wounds) | Literature reviews, evidence-based practices, current skin and wound assessment tool, and opinions and advice from wound care experts/stakeholders across Ontario were used to develop a strategy to identify patients who are at risk for skin and wound injuries at the point of entry on arrival at the emergency department | ✔ Evidence of change is based on an active approach of referral and strong line of communication between consultation, treatment and maintenance among the multidisciplinary team members |

Defining advanced practice nursing

In Canada, there are two recognised advanced nursing practice roles: clinical nurse specialist and nurse practitioner. Nurses in advanced practice roles possess education, clinical expertise, decision-making and leadership skills along with the understanding of organisation and health policy necessary to play crucial roles in both patient and system outcomes. The advanced nursing practice framework established by the Canadian Nurses Association (2024) emphasises that advanced practice nurses (APNs) contribute to the provision of timely, accessible, cost-effective and high-quality healthcare for all Canadians.

According to Davidson-Corbett et al (2023), CNSs deliver expert nursing care and take a leading role in developing clinical guidelines and protocols. They advocate for evidence-based practice, provide expert support and consultation and facilitate system change. On the other hand, nurse practitioners provide direct care with a focus on health promotion, as well as treatment and management of health conditions. Nurse practitioners operate within an expanded scope of practice that allows them to diagnose, order and interpret diagnostic tests, prescribe medications and perform certain procedures.

APN roles centre primarily around clinical engagement through direct interactions with patients or in a supportive and consultative capacity. GEM nurses, for instance, have both supportive and consultative roles within their practice. They offer valuable insights related to geriatric syndromes.

Regulation of advanced practice nursing is aligned with the scope of nursing practice and is subject to regulatory frameworks. Certain advanced nursing practice roles, such as nurse practitioner, encompass additional responsibilities that may necessitate additional regulatory authority. GEM nurses operate within the purview of the CNS role. Although they do not possess the same level of autonomy as nurse practitioners, GEM nurses can make suggestions and practice in accordance with individual institutional medical directives. For example, they may follow a medical directive to provide wound debridement if they have the requisite knowledge and expertise.

Competencies in advanced practice nursing are grounded in a thorough understanding of nursing knowledge, theory and research, complemented by extensive clinical experience. GEM nurses, often recognised as geriatric experts, exhibit their expertise through significant nursing experience in gerontology and emergency medicine as well as by holding a national certification in gerontological nursing conferred by the Canadian Nurses Association.

History of clinical nurse specialists in the Canadian healthcare system

The CNS role was introduced into the Canadian healthcare system in the 1960s. With health care becoming more complex, there was a trend towards specialisation in nursing and the development of advanced nursing practice roles. In the 1970s, the CNS role responded to an institutional need to support nursing staff at the point of care in managing complex cases and improving the quality of care (Canadian Nurses Association, 2024). The CNS role has become well established in hospitals, communities and independent practices. Research confirms the positive impact of CNS practice on the quality and cost of care (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2024).

There are no formal regulations governing CNSs in Canada, unlike in some US states where CNS is a controlled designation under the American Nurses Credentialing Center. According to Lyon and Minarik (2001),‘the practice environment of healthcare in the United States is fluid, dynamic, and sometimes chaotic. Statutory, regulatory, and credentialling requirements are critical elements of this changeable environment affecting clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) and other advanced practice nurses (APNs).’

The future of the APN role is unknown in Canada, though the author considers that the growing need for APNs is high, steadfast and expected to continue to rise.

Clinical nurse specialist definition

A CNS is a registered nurse with postgraduate preparation and expertise in a clinical specialty, such as oncology, women's health, gerontology, cardiology or mental health. CNSs work in primary, secondary and tertiary care, collaborating with multidisciplinary team members to provide health promotion, illness prevention and curative, supportive (including palliative) and rehabilitative care (Jokiniemi et al, 2023).

Clinical nurse specialist education

A CNS has a master's degree nursing, an equivalent qualification or a doctorate in nursing. CNS practice reflects and demonstrates the characteristics and competencies of advanced nursing practice, grounded in the values, knowledge, theories and practice of nursing (Wright et al, 2023).

GEM nurses in the emergency department

The ED is not adequately designed to meet the specialist needs of older patients. Environmental factors such as poor signage and cold temperatures combined with a fast-paced nature contribute to a tendency to focus solely on the patient's primary complaint. This rushed approach leaves little time to explore comorbidities and risk factors, placing older patients at risk of further adverse events (McCusker et al, 2001).

GEM nurses specialise in caring for frail, older patients aged 65 years and over. They play a crucial role in managing and resolving complex health issues, facilitating communication with community partners and coordinating with hospital resources to ensure continuity of care.

In a recent study by Foo et al (2012), a geriatric assessment and intervention led to reductions in readmittance and hospitalisation rates, ultimately enhancing the quality of care and patient experience. Morrison et al (2016) conducted a similar study, trialling a healthcare model designed to decrease preventable adverse events and reduce healthcare service use with follow-up after hospital discharge. The study outlined the approaches and outcomes of transitional care programmes provided by a master's-prepared CNS with a focus on chronic disease self-management and geriatric emergency management.

Undoubtedly, GEM nurses play a critical role in emergency care, and this programme has expanded across Canada, particularly in Ontario.

Value of GEM nurses in applying advanced wound care management

GEM nurses are recognised as geriatric experts, and there is a growing need for advanced practice clinicians who can specialise in wound care management for targeted seniors in the ED (RGPT, 2024). Although only a few hospitals in the Greater Toronto Area employ a combined approach of GEM nursing and advanced wound care management in the ED, the benefits of such a role have been demonstrated in terms of improving patient flow and enhancing the overall patient care experience (Yen et al, 2023).

In 2009, the RGPT (2024) incorporated skin wounds as one of the geriatric syndromes within the expertise of GEM nurses. However, limited attention has been given to wound care management in recent years. Difficulties have arisen because of the complexities of integrating wound care management into the GEM nurse role, resulting in some resistance observed by author at the time of this study.

Presently, in most EDs in Ontario, when patients present with complicated wounds, such as stage 3 and 4 pressure ulcers (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel et al, 2019), unstageable pressure ulcers, other unspecified pressure ulcers, soft-tissue infection, vascular ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers, they are required to wait for the assigned wound care specialist from the dedicated team that provide wound care for the whole hospital. Having to wait for wound care can significantly impact patient flow, wait times and care delivery.

A study by Calderhead and Barron (2004) emphasised the importance of emergency wound care and the need for a clinician who can provide advanced wound care management in the ED. Although they specifically considered nurse practitioners providing such services, they thought that a clinician available to offer immediate services in the ED can reduce waiting times and improve outcomes for a significant number of patients.

According to Norman (2003), high-risk populations requiring wound care include those in critical care, elderly people (especially those with femoral fractures), immunosuppressed patients, individuals with terminal cancer, diabetes or quadriplegia as well as those with heart, liver or end-stage renal disease. Risk factors such as immobility, poor nutritional status, incontinence and altered level of consciousness align with common geriatric syndromes. Yen et al (2023) indicated that GEM nurses should assess these when consulting with patients.

Education

GEM nursing is recognised as an advanced practice nursing role in Ontario. According to the Canadian Nurses Association (2024), advanced practice nurses in the province should possess a master's or doctorate degree in nursing, along with national certification specific to their practice. For GEM nurses, some institutions prefer or require certification in gerontological nursing or emergency nursing certification by the Canadian Nurses Association.

Continuing education is required for this role, including training in gentle persuasive approaches, DementiAbility Methods, P.I.E.C.E.S., U-First!, care for the elderly, cognitive assessment tools, delirium prevention and management, and seniors’ mental health (Marr et al, 2021).

Alongside education, a minimum of 3–5 years of recent experience in geriatric or emergency nursing is required. The role requires excellent interpersonal, problem-solving and teaching skills, a robust understanding of the College of Nursing of Ontario (2024) standards, and professional standards of practice in gerontology nursing (Arms et al, 2024; Canadian Nurses Association, 2024). Analytical thinking and problem-solving skills are also essential for this advanced practice role.

Waiting times, patient flow and patient and GEM nurse satisfaction and outcomes

The ED has become the primary hospital entrance point for patients, leading to frequent overcrowding. Consequently, there is a heightened focus on improving how ED services are organised to improve the patient experience. Various factors can affect patient flow and navigation within the ED. According to Johnson and Capasso (2012), improving patient flow in the ED complements the inpatient discharge process, making it crucial to view patient flow as a hospital-wide system. Identifying and addressing issues that hinder smooth flow are essential.

Although adding staff and expanding the ED are not feasible options for most hospitals, efforts can be made to improve efficiency and effectiveness through low-cost process improvements. The introduction of a GEM nurse capable of providing advanced wound care management in the ED is a promising initiative. It can significantly contribute to patient flow and navigation, especially when patients are awaiting a wound care specialist before discharge home as this study shows.

In the author's analysis of 14 patients at hospital X from March 2017 to July 2017 requiring wound checks, those who received GEM nursing referrals experienced a minimum wait time of 1.5 hours, a maximum of 4 hours, and a median rate of 2.4 hours. In contrast, patients receiving CNS referrals for wound management had a minimum wait time of 6 hours, a maximum of 24 hours, and a median rate of 13.8 hours. Notably, two patients experienced extended wait times because of limited ED staffing at weekends when the CNS was unavailable; there were no on-call CNS/wound care specialists available during weekends and holidays. In contrast, GEM nurses, particularly at hospital X, operate 7 days a week with extended hours on weekdays.

GEM nurse wound care put into practice

After conducting a rigorous needs assessment that revealed a demand for GEM nurse involvement in wound care, a pilot was run from March 2017 to July 2017. Following approval by the upper management leadership team, the initiative started in winter 2018. A key aspect of this practice role involved the author developing a wound care consultation form. This form does not replace any comprehensive geriatric assessment form already used by GEM nurses.

The new form focuses on wounds commonly seen in the ED, including pressure ulcers (all stages), venous and arterial ulcers, diabetic ulcers and soft skin tissue infections as well as other skin lesions. The GEM nurse/wound care specialist appreciates the form's comprehensiveness, finding it helpful in guiding assessments and providing recommendations for wound care management. The form includes a section for recording wound measurements and addresses pain assessment and management.

Discussion

SWOT analysis

In the case study, a SWOT analysis was chosen to systematically evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats associated with implementing advanced wound care practices in a geriatric emergency setting. This method provides a comprehensive framework to identify internal and external factors that impact the effectiveness of nursing interventions, enabling the development of targeted strategies to enhance patient outcomes.

Strengths

The main strength of this initiative was its ability to provide support in the ED to improve patient flow and navigation, and to provide the best experience possible to patients attending the ED (Welsh, 2018).

This expansion of clinical practice can also boost the clinician's professional growth in advancing their career not only in geriatric nursing care but also in the growing industry in wound care and management.

Another strength is that this initiative can promote fast, reliable and continuing wound care, with GEM nurses liaising with community partners immediately after the patient is discharged from the ED.

Weaknesses

The main weakness of this initiative is the limitation on the extent of wound care the GEM nurse can provide in practice.

Those in the GEM/wound care practice role have to complete an advanced wound care certificate or equivalent such as the interdisciplinary interprofessional wound care course at the University of Toronto or the master's in clinical science in wound healing at Western University. However, additional skills sets are necessary to provide the most expert wound care management such as debridement or for complicated wounds that are hard to diagnose (eg, calciphylaxis, pyoderma gangrenosum or other skin and soft tissue infections).

Opportunities

The major opportunity for this initiative is the growing economy and demand for professionals having sound knowledge in advanced wound care management (Welsh, 2018). From the author's observations, there are only a few frontline clinicians who focus on or have sound knowledge in advanced wound care management.

Another opportunity is that GEM nurses could support the management of geriatric syndrome (RGPT, 2024); skin and wound health is a main priority in geriatric emergency care.

Threats

The main threat to this initiative is government cutbacks that hinder wound care management. Currently, no incentives or attention are being given to wound care programmes across Ontario.

Other major threats are the legal and ethical implications of GEM nurses’ additional scope of practice in making wound care suggestions and recommendations.

Plan for sustainability

With the growing need for advanced practice clinicians who can provide advanced wound care and management, and the complexities of geriatric patients visiting the ED with wound-related concerns as comorbidities affecting functional ability, GEM nurses are a sustainable solution to this need (Welsh, 2018).

Each newly hired GEM/wound care nurse requires a master's degree in nursing or equivalent, 3–5 years’ experience of geriatric and emergency nursing care (wound care experience is an asset and preferred) and additional advanced wound care postgraduate education. Practitioners should be committed to continuing education in geriatric emergency and wound care. They need to maintain the knowledge, skills and clinical judgment for this role, which are critical to providing the best quality care for patients meeting the criteria to be seen by a GEM nurse/wound care.

A GEM/wound care nurse will report to clinical directors during monthly meetings regarding the numbers of patients visiting the ED requiring geriatric consultation, wound care management or both. They will also liaise with the organisation's CNS in wound care regarding quality improvement strategies regarding wound care.

Recommendations

The response to this initiative has been overwhelmingly positive, reflecting the growing demand for specialised geriatric programmes across Ontario. The author considers it brings cost-effective strategies to address the needs of seniors. GEM nurses at hospitals X and Y find the approach feasible and anticipate its growth, envisioning the inclusion of wound care management within the GEM programme. The initiative has shown in a favourable cost-benefit analysis, improving patient flow and navigation in the ED, enhancing patient outcomes and satisfaction with wound care management, and facilitating collaboration between GEM nurses and community partners (eg, Toronto West local health integration network) for continuity of care (Yen et al, 2023).

Identifying wound care as a geriatric issue within their practice, GEM nurses see an opportunity to competently provide advanced wound care techniques. The increasing demand for advanced practice nurses capable of offering comprehensive geriatric and wound care consultations underscores the need for training programmes at accredited nursing institutions across Canada.

The author strongly recommends extending the scope of GEM nurses in all acute care hospitals partnered with the RGPT to include non-complicated advanced wound care management in their practice.

For future researchers studying this initiative, it is suggested to explore its impact on self-esteem and self-actualisation of GEM nurses when advanced wound care is involved. Additionally, gaining an understanding the effects of this expansion on professional practice, including professional liabilities, knowledge gaps and the frequency of GEM nurses providing such wound care expertise, is essential.

Effects on practice

The position of the GEM nurse with an additional focus on wound care management has gained significant traction in Canada and beyond (Ali Mohammadi et al, 2023; Haynesworth et al, 2023).

Since the introduction of GEM programmes in Ontario in 2003, a considerable and increasing number of studies and evaluations have demonstrated the effectiveness and necessity of this model (Zhang et al, 2023; Memedovich et al, 2024). By 2017, since this case analysis was begun, the expansion of GEM nursing to include advanced wound care management has highlighted the critical need for specialised care in the ED, particularly for frail seniors with complex medical needs.

Recent studies have continued to support the relevance and effectiveness of GEM nurses in providing high-quality, targeted care for geriatric patients (Gagliano et al, 2023; Karaca et al, 2024). These studies have shown that GEM programmes not only improve outcomes but also enhance patient satisfaction, reduce unnecessary hospital admissions and streamline patient flow within the ED. The incorporation of advanced wound care management has further solidified the importance of GEM nurses, as this additional focus addresses a prevalent and challenging aspect of geriatric care.

The GEM nursing model has recently been adopted by several health institutions in the USA (Haynesworth et al, 2023). This reflects the global recognition of the GEM nursing model's value in addressing the specialist needs of the geriatric population in emergency settings. US health institutions have integrated GEM nurses into their EDs to provide comprehensive geriatric assessments and advanced wound care management, replicating the positive outcomes seen in Ontario. (Levine, 2022).

Conclusion

There is a continued need for innovation in advanced geriatric nursing, with nurse specialists and leaders continuously shaping the future of nursing in today's evolving healthcare system.

The ongoing expansion of GEM nursing roles, both in Canada and internationally, underscores the growing demand for specialised geriatric care. As the population continues to age, the need for advanced practice nurses who can address the complex medical, psychological and social needs of seniors becomes even more critical.

GEM nurses, equipped with expertise in geriatric syndromes and advanced wound care, are well positioned to meet these needs, ensuring that seniors receive the best possible care in emergency settings. Therefore, the continuous development and evaluation of GEM programmes, including cost benefits, patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes, will be essential in sustaining and expanding this model.

As more healthcare systems recognise the benefits of GEM nursing, the role of GEM nurses will likely continue to evolve, incorporating new evidence-based practices and innovations in geriatric care.

CPD reflective questions

- How could integrating advanced wound care into geriatric emergency management (GEM) nursing improve patient outcomes in your emergency department? Consider the potential benefits and challenges

- Reflect on the practices in your emergency department for managing frail older patients. What strategies could enhance their assessment and care, particularly regarding complex medical conditions and atypical disease presentations?

- How can you support and encourage your nurses to acquire advanced skills in both geriatric care and wound management to meet the needs of the rising number of older people visiting the emergency department?

KEY POINTS

- Emergency department visits by older patients are rising, and these patients often have complex medical and psychosocial conditions

- Geriatric emergency management (GEM) programmes are effective in providing specialised, frailty-focused nursing services

- GEM nurses play a crucial role in assessing and managing the health and wellbeing of frail seniors, preventing unnecessary hospital admissions, and ensuring better continuity of care through community connections

- The integration of advanced wound care into the GEM nursing scope of practice has shown promising results, with patients experiencing shorter wait times and improved care outcomes

- Advanced practice nurses trained in both geriatric and wound care are needed, and GEM programmes should be expanded to include comprehensive wound management

- More evidence on the cost-effectiveness of GEM programmes is needed