Children with neurological impairment often require enteral tube feeding to maintain their nutritional status and growth. Advances in all aspects of medical care, including this level of nutrition support, has been associated with an increase in the life expectancy of children with neurological impairment (Trivić and Hojsak, 2019). The European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (Romano et al, 2017) recommend that children with neurological impairment who have a long-term requirement for enteral tube feeds have a gastrostomy tube placed.

The gold standard method of providing nutrition and hydration to neurologically impaired children is the administration of a nutritionally complete commercial formula (Epp et al, 2017). Historically, health professionals have considered the use of commercial formulas to be safe, easy for families to use, readily quantifiable and portable. However, in recent years many families have shown interest in the administration of a blended diet. This is where food is blended and mixed with an appropriate fluid - for example, commercial formula, water or juice – and administered via enteral feeding tubes. The blended diet might be given in conjunction with, or in replacement of, commercial formula. It has been suggested that a blended diet is more natural and potentially better tolerated than commercial formulas.

Retching, vomiting and abdominal pain are well-documented problems experienced by children with neurological impairment, which may be exacerbated by the prolonged use of sterile commercial formula (Hauer, 2018). The gastrointestinal tract is one of the most frequently attributed sources of pain in children with neurological impairment, and they are commonly diagnosed with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and constipation. Worsening feed tolerance and escalating distress symptoms often lead to malnutrition and reduced quality of life (Dipasquale et al, 2019).

Anecdotal evidence suggests that children who receive a blended diet via their gastrostomy tube have reduced symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux, constipation, gagging and retching, particularly post fundoplication (Coad et al, 2017). However, the evidence is limited and often of low quality. Reported risks associated with the administration of blended diet include poor growth, micronutrient deficiencies and microbial contamination, although these concerns seem to be seen in clinical practice rarely (Poole et al, 2021). It is imperative that children commencing on a blended diet are supported by a specialist multidisciplinary team including a specialist dietitian (British Dietetic Association (BDA), 2021) to mitigate these risks.

Administering food via feeding tubes is not a new phenomenon. Records from the Egyptians in 1500 (Chernoff, 2006) show that the sick received rectal feeds of beef, wine, eggs, wheat and barley broths via clay pipes. Initial experiments in the 1800s to access the upper gastrointestinal tract to provide nutrition resulted in poor outcomes; however, advances in surgical techniques and medical devices saw the widespread use of enteral nutrition in the 1900s (Chernoff, 2006). Blended diets were initially prepared in the hospital setting and administered via nasogastric tubes. By the 1960s and 1970s, advances in enteral nutrition resulted in the medicalisation or commercialisation of feeding, with a gradual reduction of blended tube feeds and an increase in the use of nutritionally complete commercial formulas. Within the Royal Hospital for Children, a large tertiary centre, the tide now appears to be turning, with increasing numbers of tube-fed patients receiving blended diets.

Aims

Since early 2017, the Complex Enteral Nutrition service and Paediatric Dietetic service has been supporting children to commence a blended diet in the community setting. However, it was noted that there was no process in place for when these children required an inpatient admission. This article describes the multidisciplinary team's experience of creating safe, robust pathways to allow children to receive blended diet while an inpatient in the large tertiary paediatric centre.

Method

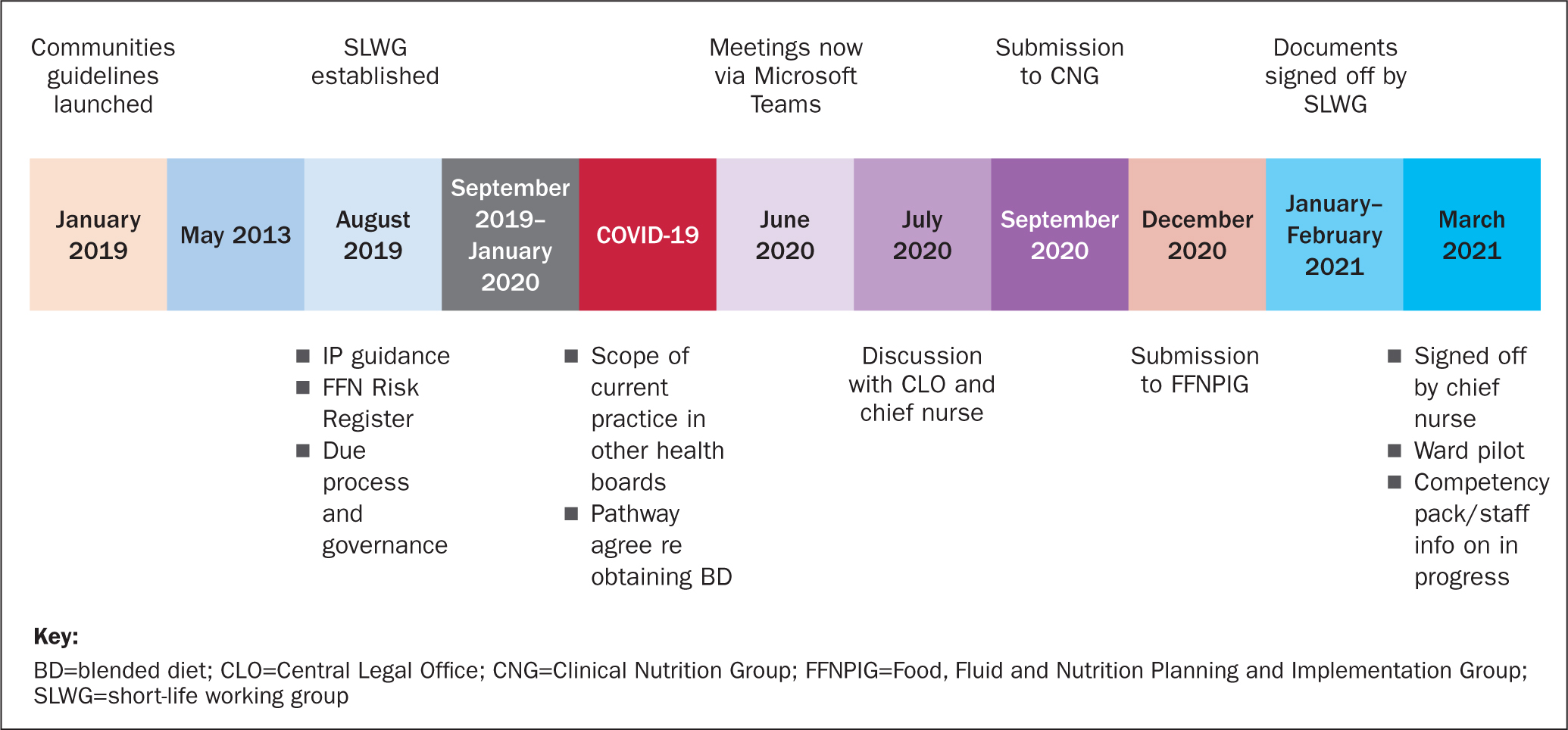

Following the launch of community blended diet guidelines in 2019, blended diet was added to the dietetic risk register within NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (GGC). It was highlighted at this time that due process and governance was required to create guidance for the administration of blended diet in the acute setting. A short-life working group (SLWG) was established, with representation from the nutrition support team, paediatric dietetics, ward staff, food fluid and nutrition nurse specialists, the catering strategy dietitian, catering management and the infection control team, who all contributed to creating this documentation. Subsequent to the initial meeting, contact was made with senior management in the NHS board, who supported the endeavour, leading to a number of meetings and workstreams, which are illustrated in the timeline (Figure 1).

Evolution of documentation

A scoping exercise of current practice within other NHS boards and trusts was carried out. This demonstrated significant differences in practice across the UK, which ranged from no guidance to full guidance and, where guidance existed, this detailed the nutritional content of specific meals and volumes of fluids to be added to ensure appropriate consistencies. These practices were reviewed and, following discussion with our local environmental health officer and catering manager, it was agreed that level 3 of the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) (2019) texture-modified diet (TMD) could be used within NHS GGC. However, within the hospital this consists mainly of soups and puddings and therefore would not be suitable for children in the longer term. Consequently, it was also agreed that level 4 IDDSI TMD meals could be used, due to the availability of a larger variety of meals. However, it was noted that meals would require extra fluid to be added to ensure they were of an appropriate consistency for administration via a gastrostomy tube. These meals come from an external provider and are heated to an appropriate temperature, thereby meeting all food safety standards.

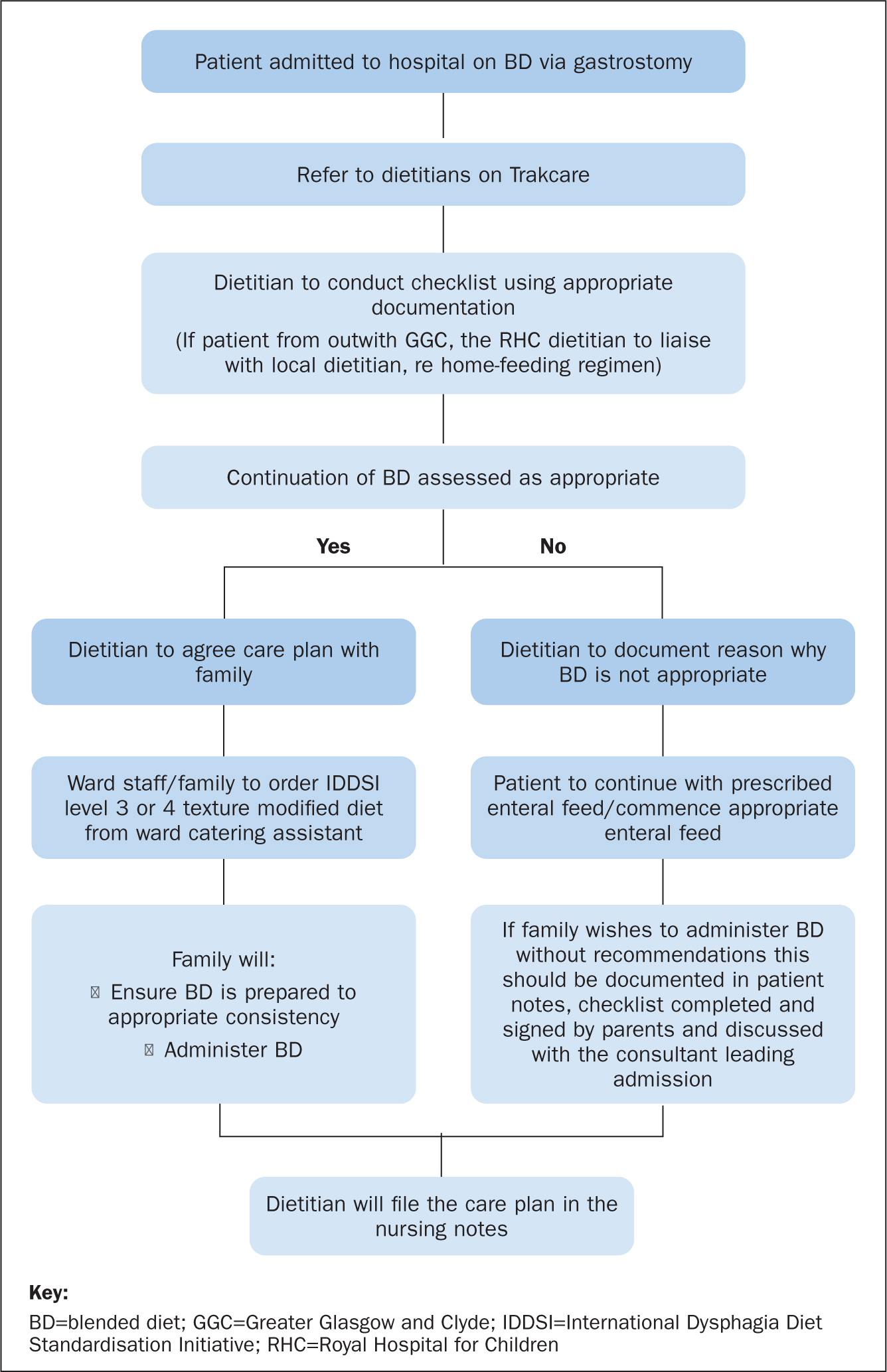

The SLWG devised a pathway to enable meals to be ordered via the catering department, which parents/families could then administer on the wards (Figure 2).

During the creation of this pathway, it was highlighted that an assessment was required for each new admission to ensure that it was appropriate for individual patients to be fed with blended diet during their admission. All of the documentation developed by the SLWG was discussed with the health board's Central Legal Office (CLO). Following CLO advice, the ‘inpatient blended diet risk assessment’ was renamed a ‘checklist’ (Table 1).

Table 1. Blended Diet Inpatient Checklist NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Does the child usually have blended diet (BD) at home | ||

| 2. Has a full risk assessment for BD been completed previously? | ||

| 3. Has the BD competency package been completed? | ||

| 4. Does the child have a gastrostomy button (of any size) or a gastrostomy tube that is at least 14 Fr bore? | ||

| 5. Has the medical/surgical team agreed that the child can continue with BD during this admission? | ||

| 6. Is the hospital admission expected to be short term (less than 1 week)? | ||

| 7. Does the child have any food allergies? | ||

| 8. Will the child have a parent/carer present during the admission to administer the BD? | ||

| 9. Does the parent/carer feel confident in ensuring the BD is prepared to an appropriate consistency prior to administering it? | ||

| 10. Does the parent/carer understand/agree that homemade blends, personal blenders or pumps must not be used for BD in hospital? | ||

11. Has food safety been discussed the with parent/carer and have they been given the following written information?

|

||

| Individual risks identified ……………………………………………………………………………. | ||

| Can the child continue to receive BD in hospital? YES/NOIf no, specify reasons ………………………………………………………………………………… | ||

| This checklist can be reviewed should there be a change in circumstances, eg when the child becomes clinically fit for BD | ||

Both the pathway and checklist ensure that children are referred to the dietetic service on admission. If the circumstances around a child's admission mean that it is inappropriate for them to receive a blended diet at that time, this is documented within the checklist and the parents are asked to sign the form to acknowledge the advice they have been given. Advice was also sought from CLO as to whether a disclaimer would be good practice should a family not accept the outcome of the dietetic assessment. However, the CLO advice was that a disclaimer would not be helpful because health professionals are duty bound to step in should they witness a potentially harmful event on the ward – in other words, parents or guardians cannot simply sign a disclaimer and then proceed to carry out an unsafe action.

It was recognised that not all dietetic staff would feel confident in the process of initiating blended diet in the acute setting. A supplementary dietetic information pack was created including the nutritional composition of the TMD meals available within the health board. This also detailed the process for accessing blended diet on the wards, how to complete the checklist and how to assess if continuing blended diet was appropriate. Furthermore, it was felt that parents may seek further information regarding the processes used and their own ability to provide blended diet to their children during the inpatient stay, so a patient/parent information leaflet was also produced. This leaflet outlines the health board's general information regarding food and drink in hospital, specific information regarding meals that can be provided and how these should be stored and administered. The leaflet also outlines some of the rationale on why certain foods could not be brought into the hospital.

All documentation was then submitted to the health board's Clinical Nutrition Group and Food, Fluid and Nutrition Planning and Implementation Group for agreement. The planned next step is to commence a pilot study within the paediatric neurology ward to assess the efficiency of the pathways. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has halted this at present.

Moving forward

We recognise that the ability to provide a blended diet for our acute patients has a huge impact on their health and wellbeing, and can reduce stresses and anxieties for parents around symptoms returning if their child has to be fed using a commercial formula while an inpatient. At present a blended diet is administered within the hospital setting only by parents and carers.

The authors' ward representatives felt strongly about being able to administer blended diet to patients, however it was recognised that training would be required - in particular to ensure that the blended diet is of the correct consistency. At present, the SLWG is liaising with acute hospital education staff to create a teaching document that will in time allow nurses and healthcare assistants to provide blended diets to children within the ward areas. Furthermore, the Complex Enteral Nutrition service is actively pursuing the development of a blended diet dietitian role, which will be the first of its kind within the UK. Within this large tertiary centre the authors are keen advocates of the use of blended diet for children with neurological impairment with poor gastric feed tolerance, and will continue to carry out research assessing growth, micronutrient status and the impact on children's and families's quality of life following the initiation of blended diet.

Conclusion

Life expectancy for children with neurological impairment is increasing, with many requiring enteral tube feeding to ensure adequate nutrition and hydration. As these children are getting older, their gastrointestinal symptoms and ability to tolerate commercial feeds can deteriorate. Blended diet is a treatment option for children with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, retching post fundoplication and distress with feeding, however, this must be undertaken with full multidisciplinary team involvement to reduce the risks of poor growth and micronutrient deficiencies.

This article has described the processes that the authors' multidisciplinary team SLWG has been through to create robust and safe pathways for the administration of blended diet within the acute setting following discussions with the CLO and senior hospital management. Moving forward the SLWG will be implementing a pilot study using the newly developed documentation and processes to assess inpatients for blended diet suitability within the neurology ward prior to rolling out this system across the hospital. Once this step has been completed, the authors will be engaging in a programme of training to enable nurses and HCAs to administer blended diet to inpatients.

Our centre remains a keen advocate for the use of blended diet, and we are therefore continually updating our data on the growth and micronutrient status of children within our service who receive blended diet, to ensure that patients remain safe and well at all times.

KEY POINTS

- Children with neurological impairment are surviving longer due to advances in medical technology and support with nutrition and hydration

- Blended diet (BD) is not a new phenomenon, however many families are becoming more interested in this due to perceived benefits, such as a reduction in gastrointestinal symptoms

- Many hospital trusts have devised their own guidance for the use of BD within the community settings, but there is little information regarding the use of BD in the acute setting

- A multidisciplinary short-life working group has created safe and robust pathways for children to access BD in the acute setting

CPD reflective questions

- What is your experience of blended diet in children with neurological impairment?

- Are you aware of what your local health board's policy is with regard to the administration of blended diet in the acute setting?

- What is your experience of administering blended diet to children in the acute setting?