Gestational cancer is defined as any type of cancer diagnosed within 3 months before abortion, within 9 months before delivery, or within 12 months of delivery. A report by the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service (NCRAS) and Public Health England (2018) estimated that 1 in 1000 pregnancies have the added complication of a cancer diagnosis (dual-diagnosis). NCRAS data from 2012-2014 revealed there was a gestational cancer diagnosis for 3272 women aged between 15 and 44 in England. The highest incidence of gestational cancer was of the breast (n=784), followed by melanoma of the skin (n=504), cervical cancer (n=498), haematological cancer (n=296), ovarian cancer (n=240) and colorectal and anus cancer (n=188); these account for 76% of all the observed cases. Eastwood-Wilshere et al (2019) suggested that the rate of gestational cancer is increasing because women choose to delay pregnancy until later in life.

Although a gestational cancer diagnosis affects only a small percentage of pregnancies, it has a significant impact on the psychological wellbeing of those women affected and their partners. Ferrari et al (2018) highlighted the unique and specific challenges women diagnosed with gestational cancer face, confronted with the paradox of creating new life while experiencing a challenge to their own mortality. The dual-diagnosis of life-changing events at opposite ends of the spectrum is likely to exacerbate the emotional vulnerabilities of women, who have to learn two new sets of medical terminology and make sense of information they receive from health professionals, in order to make decisions that may impact on the life of their unborn child or themselves (Leung et al, 2020). The concerns of such women are perpetuated following treatment, as they continue to worry about the impact on bonding and attachment with their baby, as well as the health and developmental progress of a child exposed to chemotherapy in utero, their own future fertility, and the safety of future pregnancies.

This literature review aims to answer the question: ‘What is the psychological impact for women who receive a diagnosis of gestational cancer?’. It is hoped that the findings will broaden nurses' and midwives' understanding and so enable enhanced delivery of support and care.

Method and search strategy

The ‘Population, Exposure, Outcome’ framework (Polit and Beck, 2014) was used to develop the research question. The ‘population’ was pregnant women, the ‘exposure’ was gestational cancer diagnosis and the ‘outcome’ was the psychological impact. A systematic search was carried out in November 2020, using the Medline, CINAHL Complete, PsycINFO and Complementary Index databases, using key words and synonyms closely aligned with the research question (Table 1). Boolean operators were used to focus the search on the research question.

Table 1. Search terms

| Cancer patients ‘OR’ oncology patients ‘AND’ pregnancy ‘OR’ gestational |

| Pregnancy complications OR cancer |

| Gestational cancer ‘NOT’ diabetes |

There were 250 results returned after removing duplicate research articles. These were filtered using inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). All studies focusing on gestational trophoblastic disease were excluded, as these pregnancies are not viable.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Full text | Research published before 2010 |

| Double-blind peer reviewed | Not gestational cancer |

| English language | Focus on gestational trophoblastic disease (including molar pregnancy and placental cancer) |

| Clear focus on gestational cancerClear focus on the psychological impact of a gestational cancer diagnosis |

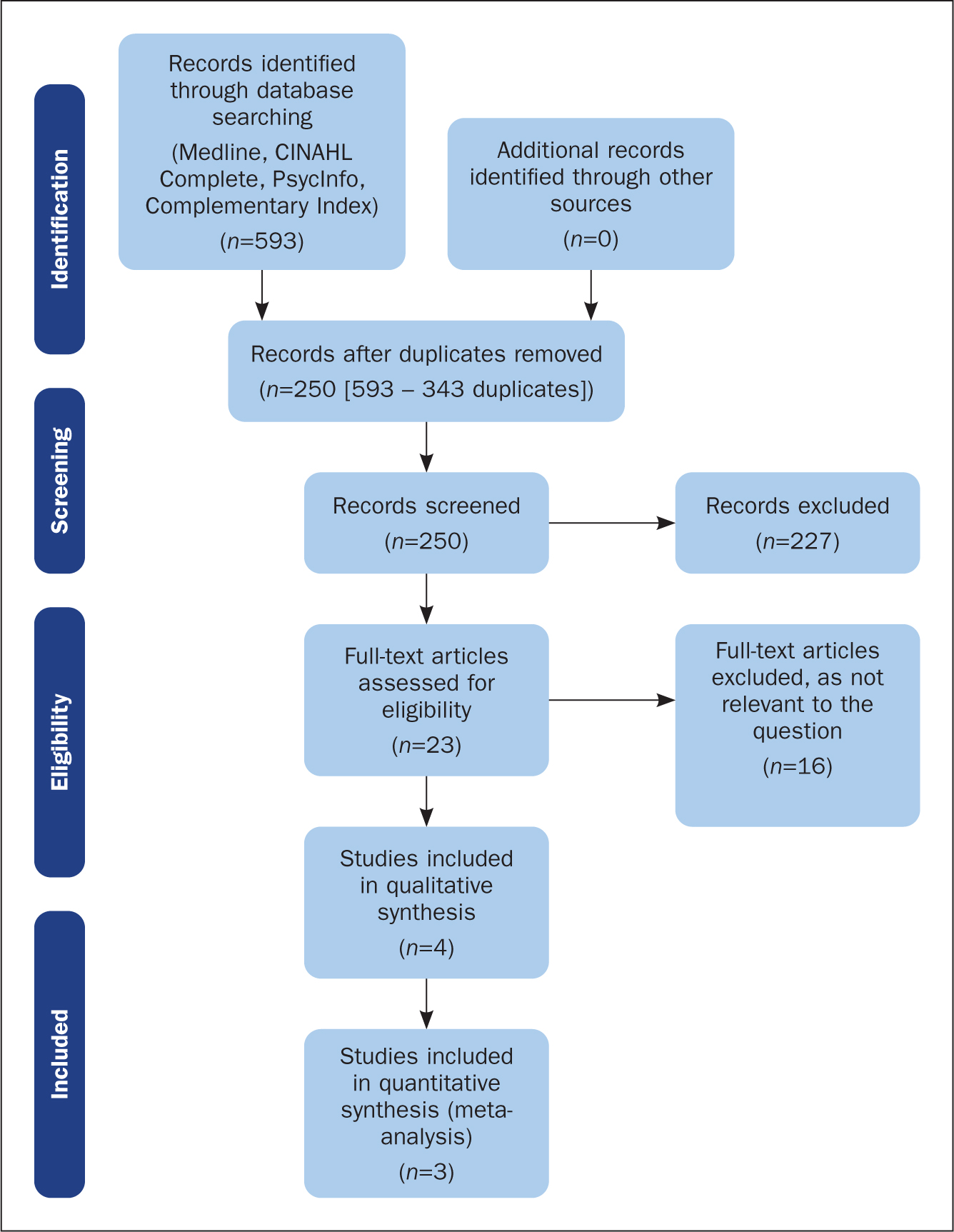

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (see Figure 1) was used to depict the process of filtering the articles (Moher et al, 2009). After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 227 articles were discarded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 23 research articles were read in full and a further 16 of these articles were discarded, due to insufficient focus on the research question. The seven remaining articles were analysed using the relevant Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist (CASP, 2022). All the studies were deemed to be of high quality based on the CASP review, thus relevant for inclusion in the review.

Data from the final seven articles were plotted into tables of findings, reflecting the quantitative (Table 3) and qualitative (Table 4) approaches. The primary researcher (FR) undertook a narrative analysis of the quantitative data, then cross-tabulated the areas of psychological concern with the qualitative data, as described below. Emerging themes were developed during supervision with an academic and small groups of final-year nursing students.

Table 3. Summary of quantitative data

| Author, date and country | Patient group | Research method | Research tools | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4. Summary of qualitative data

| Author, date, country | Patient group | Research method | Research tools | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Theme 1

|

|

|

|

|

Theme 1

|

|

|

|

|

Theme 1

|

|

|

|

|

Theme 1

|

BC=breast cancer; GBC=gestational breast cancer

Findings

Narrative analysis of quantitative data

See Table 3. Henry et al (2012) used self-administered questionnaires to explore the psychological impact of a gestational cancer diagnosis in 74 women in the USA. Participants completed the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 and Impact of Events Scale, on average 3.8 years following their cancer diagnosis. Data analysis revealed that 20.9% (n=28) women experienced significant levels of distress linked to their diagnosis. Distress was most profound with regard to the need for prompt clinical decision-making, particularly when women overruled clinicians' advice to terminate their pregnancy, when they were advised to deliver preterm or to undergo surgery post delivery, describing how they felt unsupported.

In their research, Vandenbroucke et al (2017) sought to identify women and their partners at high risk of distress based on their coping profile. Data revealed that women and their partners experienced a similar level of distress. In total, 61 pregnant women and their partners completed the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) and the newly constructed Cancer and Pregnancy Questionnaire (CPQ). Findings confirmed that distress was inextricably linked to the coping mechanisms women and their partners used, especially where they internalised their concerns about the cancer/pregnancy/child's health (n=20; 32.8%). Where positive coping strategies were used (no specific examples given) or where blame was placed on others, the potential for distress was lower.

Betchen et al's (2020) study of 69 women and 71 children (two sets of twins) aged between 6 months and 12 years, sought to explore the relationship between child development and women's psychosocial wellbeing following a gestational cancer diagnosis. They discovered an inverse relationship between the distress displayed by mothers as depression, anxiety and pain, and their children's language skill development. Further, they demonstrated how the children of mothers with psychosocial symptoms displayed higher levels of behavioural challenges.

The quantitative data revealed areas of psychological concern for women diagnosed with gestational cancer. It offers evidence of correlation between psychological impact, coping mechanisms and child development.

Thematic analysis of qualitative data

The primary researcher (FR) analysed the qualitative data, developing three themes that both reflected and built on the areas of psychological concern highlighted in the quantitative data:

- Theme 1: time pressures and decision-making, balanced with concerns for the health and wellbeing of the baby and self

- Theme 2: fears about parenting

- Theme 3: the influence of support.

Theme 1: time pressures and decision-making balanced with concerns for the health and wellbeing of baby and self

See Table 4. Time was a key trigger for distress about treatment decision-making. Kozu et al (2020) interviewed eight postpartum women who had made decisions about treatment while pregnant. Participants described distress incurred by necessary decision-making about cancer treatment and the progression of pregnancy, within the limited time frame of the pregnancy. They described tensions around delaying cancer treatment to advance the pregnancy, experiencing anxiety and uncertainty as a result of the haste of medical meetings, reinforcing the findings of Henry et al (2012).

Ives et al (2012) carried out semi-structured interviews with 15 women who were diagnosed with gestational breast cancer. Participants described feeling stressed and anxious in relation to the thought of receiving treatment. This was intensified when they received conflicting advice from their obstetrician and oncologist. Hammarberg et al's (2018) phenomenological study of 17 Australian women diagnosed with gestational breast cancer in the preceding 5 years highlighted feelings of distress when they experienced communication difficulties and inconsistencies between members of the interdisciplinary team as a result of the way that information was communicated to them, especially when it related to information about the best treatment option and impact on survival.

Time pressures and decision-making is naturally balanced with concerns for the health and wellbeing of the baby and the self. Faccio et al (2020) collected qualitative data from 38 women, 19 of whom had gestational breast cancer (GBC) and 19 who did not. Thematic analysis of interview data confirmed women with GBC were afraid for their own survival, as well as that of their child, due to the risk of stillbirth or premature delivery, compared with women without GBC.

Both Hammarberg et al (2018) and Kozu et al (2020), who explored the lived experiences of eight women with gestational cancer, reported women's persistent fears about the impact of the side-effects of cancer treatment on the fetus, whether the development of a disability or the cause of a preterm delivery. These fears were balanced against the survival of the mother but were important to decision-making. Vandenbroucke et al's (2017) study revealed that multiparous parents prioritised their own health so that they could protect the children they already had, whereas nulliparous parents had more concern for the fetus. Betchen et al (2020) reported that 68% of mothers in their sample received treatment for their gestational cancer, but experienced major anxiety as a result.

The data in this theme clearly presents the psychological impact of a diagnosis of gestational cancer, with the specific additional complexity of considering the health of the fetus that they are carrying, along with their own health. The act of treatment decision-making, within the time frame of the pregnancy, added additional pressure for women, which may be compounded by inconsistent information and a sense of conflicting priorities of the oncology and maternity teams.

Theme 2: Fears about parenting

Fears about parenting reflects specific concerns such as bonding and attachment with the baby and broader fears focused on being ‘inadequate mothers’, whether in the short term due to hospital appointments and the side effects of treatment such as fatigue (Faccio et al, 2020, Kozu et al, 2020), or in the longer term. Some women expressed fears about caring for themselves and a disabled child, where disability is linked to receiving cancer treatment (Kozu et al, 2020). Where mothers had a diagnosis of GBC they had specific concerns around their potential inability to breastfeed, viewing breastfeeding as fundamental to bonding with their baby (Faccio et al, 2020). Fears about parenting extended to the consideration of the impact of cancer treatments on fertility for future pregnancies (Ives et al, 2012; Hammarberg et al, 2018; Kozu et al, 2020). Distress was exacerbated when women were in receipt of inconsistent information from health professionals.

The data in this theme highlighted women's fears about the uncertainties around the side effects of cancer treatment for both mother and baby, whether their survival, or disability arising from the treatment. It reflects fears around breastfeeding for women with GBC specifically and generalised concerns about the effects of treatment or time pressures of hospital visits impacting on the process of bonding with their baby.

Theme 3: influence of support

The qualitative data in this review presented clear evidence of the influence of support on women diagnosed with gestational cancer, particularly in relation to the psychological impact. Predominantly, participants described ‘poorly co-ordinated and unsatisfactory care’ from health professionals, who made them feel like ‘misfits’ and caused them to feel disempowered as it impacted on the action of shared decision-making (Hammarberg et al, 2018). Gender-specific nuances were noted as influential in relation to support. Kozu et al (2020) described how women's distress was worsened by having to communicate with young male doctors, since the women felt these doctors were unable to relate to their current situation.

Women with GBC who had access to a dedicated breast care nurse reported that it had a positive impact on their experiences of care (Hammarberg et al, 2018). These participants also reported feeling supported through access to counselling and peer support groups, but highlighted that, because gestational cancer is so rare, they felt ‘out of place’ at times. One woman with GBC, who had a single mastectomy but wanted to breastfeed, reported a strong sense of isolation when receiving care on the maternity unit, leaving her feeling unsupported (Ives et al, 2012). Women predominantly relied on their partners and family members to manage their distress (Ives et al, 2012; Hammarberg et al, 2018; Faccio et al, 2020). Women in several studies stated that the fetus itself was a source of strength and support to them (Faccio et al, 2020), especially when they felt that it was respected (Kozu et al, 2020).

Women in the studies reviewed appear to rely predominantly on their partner and family for support. Notably, psychological distress was associated with poor support from health professionals, inconsistencies in information about treatment, and differing care priorities between members of the interprofessional team. The way that information was delivered to the women and their partners was central to the care experience. The data reinforces the importance of appropriate support systems, such as access to breast cancer clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), being in place as a way to enhance women's experiences of care.

Discussion

The three themes that developed from the data have a common element of communication, particularly consistency of communication, running through them. Where communication was poor or inconsistent, women in the studies experienced distress and anxiety and felt disempowered in the decision-making process. The feelings of distress may continue several years beyond remission from the cancer and can impact on the wider family, as mothers balance concerns for their own and their baby's health with concerns about their functional ability to parent, while continuing to need support themselves (Schmitt et al, 2010). A recent systematic review by Leung et al (2020) supported the findings of this literature review, highlighting the distress caused by women's concerns about their baby and the pressures of decision-making.

The Mental Health Foundation (2018) suggested that one in three people with a diagnosis of cancer (not gestational cancer specifically) will experience a mental health condition such as anxiety or depression at some point during their diagnosis and recovery, linking this to communication between service providers and a lack of support after treatment has finished. The data in this literature review confirm that women with gestational cancer are very likely to experience distress and anxiety that persists beyond diagnosis and treatment. It often begins with anxiety linked to communication and inconsistency of the message being communicated, reflecting inadequate communication between the oncology and obstetric teams (Ives et al, 2012, Hammarberg et al, 2018, Kozu et al, 2020). Although work has been done to improve the support available for women with a gestational cancer diagnosis (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2019; Brauten-Smith, 2020; Mummy's Star, 2020), including the provision of advocacy services, the Mental Health Foundation (2018) argued that person-centred care and greater collaboration and communication between service providers, in this case the oncology and obstetric teams, is needed. Notably, Vandenbroucke et al (2017) found that the use of the CERQ and the CPQ tools enabled professionals involved in a women's care to predict whether they would benefit from additional psychosocial support to help them manage their distress.

Having a clear understanding of all their options for treatment is fundamental to person-centred care and it is important that women and their partners are involved in all decisions regarding treatment and progression of the pregnancy, as advocated by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2011). The data in this literature review reveals that women and their partners continue to experience distress and feel disempowered because they experience poor or inconsistent communication between and from health professionals that results in conflicting advice (Ives et al, 2012; Vandenbroucke et al, 2017; Hammarberg et al, 2018; Kozu et al, 2020). This finding suggests that there is a potential to improve services and thus improve the experience of women diagnosed with gestational cancer, namely by enhancing collaboration and communication between service providers.

Implications for practice

Implications for practice identified from this review are to improve the communication and consistency of information between the oncology and obstetric teams and to promote the use of assessment tools, such as the CERQ and CPQ, to identify women likely to need additional psychosocial support, so that suitable support can be arranged or referrals to other services made (Ives et al, 2012; Vandenbroucke et al, 2017; Hammarberg et al, 2018).

Eastwood-Wilshere et al (2019) proposed that women with gestational cancer need to be managed in a multidisciplinary high-risk obstetric unit, with involvement from obstetrics, obstetric medicine, oncology, radiation oncology, radiology, palliative care, midwifery, nursing and social work. Continuity of care from a named midwife has been shown to have a significant positive impact on the experience of pregnancy and childbirth (Sandall et al, 2016). In their review of services, Sandall et al (2016) presented the model used at Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust in London, where the booking midwife co-ordinates all antenatal and postnatal care and attends all multidisciplinary consultations for those women at high medical risk. This ensures that the women have access to specialist services and shared care plans. It is highlighted as an effective model for practice that would benefit all women diagnosed with gestational cancer, since it supports consistency of messages about treatment and obstetric concerns through a named midwife during the pregnancy.

Effective communication is a fundamental nursing and midwifery role (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018). The named midwife is well placed to administer CERQ and CPQ assessment tools, and to initiate or signpost women and their partners to appropriate support services during the pregnancy. Macmillan, Breast Cancer Now and Mummy's Star offer support and advocacy, both during the pregnancy and afterwards. CNS roles are well established in oncology. A close working relationship between the named midwife and the CNS within the multidisciplinary team will support handover of care from the obstetric team to the oncology team following delivery of the baby, in order that a woman's needs continue to be supported in a seamless way during oncology treatment and follow-up care.

Limitations

There is a limited number of articles exploring women's experiences of gestational cancer available for review. Available articles predominantly rely on participants who are postpartum, so there is a potential for recall bias to influence the findings. Many women who participated were disease-free so data from potential participants continuing to live with gestational cancer is missing. In addition, there is a bias towards research with women diagnosed with GBC, where there are specific concerns raised around breastfeeding, an act that is heavily linked to the process of bonding with a baby. These factors may have influenced the findings of this literature review.

Conclusion

In conclusion, women with a diagnosis of gestational cancer have been found to experience feelings of distress about their diagnosis and treatment. This is linked to the need to make quick decisions about treatment due to the limited time frame of the pregnancy, balancing concerns for their own health and that of their baby. The distress is clearly exacerbated by conflicting priorities for care, inconsistencies of information about treatment between members of the multidisciplinary team, and the way that information is communicated. Communication and support are enhanced when women have a named midwife. Effective communication is supported when a named midwife attends all multidisciplinary meetings concerning women with medical risk due to a diagnosis of gestational cancer. The use of cognitive assessment tools can help to highlight women at higher risk of psychosocial distress in order that appropriate support services are initiated or signposted. Following the birth of the baby, the named midwife should ensure a clear handover to the oncology CNS, in order to ensure continuity of care and support for the woman and her partner as required.

KEY POINTS

- Women diagnosed with gestational cancer have unique support needs arising from receipt of a devastating diagnosis at what should be a happy time

- Women and their partners face time pressures around decision making, balancing the need for treatment for the mother and the potential impact of treatment on the fetus and may, in some cases, be faced with decisions about terminating the pregnancy

- The experience of being under the care of two discrete teams can result in uncertainty and distress if inconsistent messages about treatment are given

- Support can be significantly enhanced by having a named midwife who attends all multidisciplinary team meetings about the woman, who can assess for distress and who can signpost psychosocial support, based on the individual woman's needs

CPD reflective questions

- Describe the benefits of effective interprofessional communication for the woman diagnosed with gestational cancer and her partner

- Reflect how your understanding of the complexities of receiving simultaneous care from multiple professional teams can help you to enhance the experience of care for patients you work with

- Consider how the use of questionnaires/tools can help you to identify patients at risk of psychological distress in order that you can signpost or make appropriate referrals to support services