The use of digital applications to promote health literacy is increasingly becoming the focus of interest (Matusiewicz, 2018; Dietscher, 2020), with their use shown to have a positive impact on health- or disease-specific knowledge (Wintner, 2015; Rasmussen et al, 2016; Sood et al, 2018). However, in an international context, the Austrian population was found to have showed below-average (54.8%) health literacy (Pelikan et al, 2012).

Research has demonstrated that people with lower health literacy are less likely to use digital apps for health and disease management, due to limited technology skills and lack of access to equipment (Jeong and Kim, 2016). Consequently, the Austrian government's efforts to increasingly integrate digital solutions into health care risk excluding vulnerable groups (Mackert, 2016; Fonds Gesundes Österreich, 2019).

To date, in Austria, there have been no published studies on the health literacy of patients in connection with the use of digital apps in health and disease management. Existing research has primarily focused on quantitative approaches, taking into account age, gender, social status and education level (Dietscher et al, 2020). Qualitative findings, however, can make a valuable contribution to better understanding patients' subjective attitudes and perceptions.

Research questions

The following primary research question was formulated to address the focus of interest:

- Taking digital applications into account, what are the attitudes and perceptions of patients with regard to their health literacy?

To ensure a more detailed examination of the subject area, two secondary research questions were formulated.

- How well do inpatients accept digital apps in health and disease management?

- What are the expectations from, and challenges of using, digital apps in health and disease management?

Method

The study used a phenomenological approach, which has its origins in philosophy and aims to capture subjective impressions and sensations. The resulting analyses aimed to provide a better understanding of the behaviours and reactions of individuals in daily living (Lamnek, 2010; Mayring, 2015).

Data collection

Data collection was conducted by a nurse (MK, lead author) between November 2019 and March 2020 using guided in-depth interviews. These were conducted with patients at an Austrian hospital, with the nursing management enabling access. In co-operation with the responsible ethics committee, the patient inclusion criteria were defined as:

- Participation was voluntary

- Patients had an existing acute or chronic illness

- They were receiving nursing-medical treatment in the hospital (excluding palliative and intensive care units or surgery)

- They were aged 18 years or older

- They had good knowledge of German or English

- They had no cognitive impairments.

To recruit participants, information leaflets with contact details were placed in waiting rooms and common rooms of the respective wards, to enable patients to express an interest in participating. Those who expressed an interest received a verbal explanation of the project and written informed consent was obtained. The interviews were either face-to-face in the hospital or done via telephone. Subjects received an expense allowance in the form of a €10 leisure voucher, which was approved by the ethics committee and the nursing director.

Data analysis

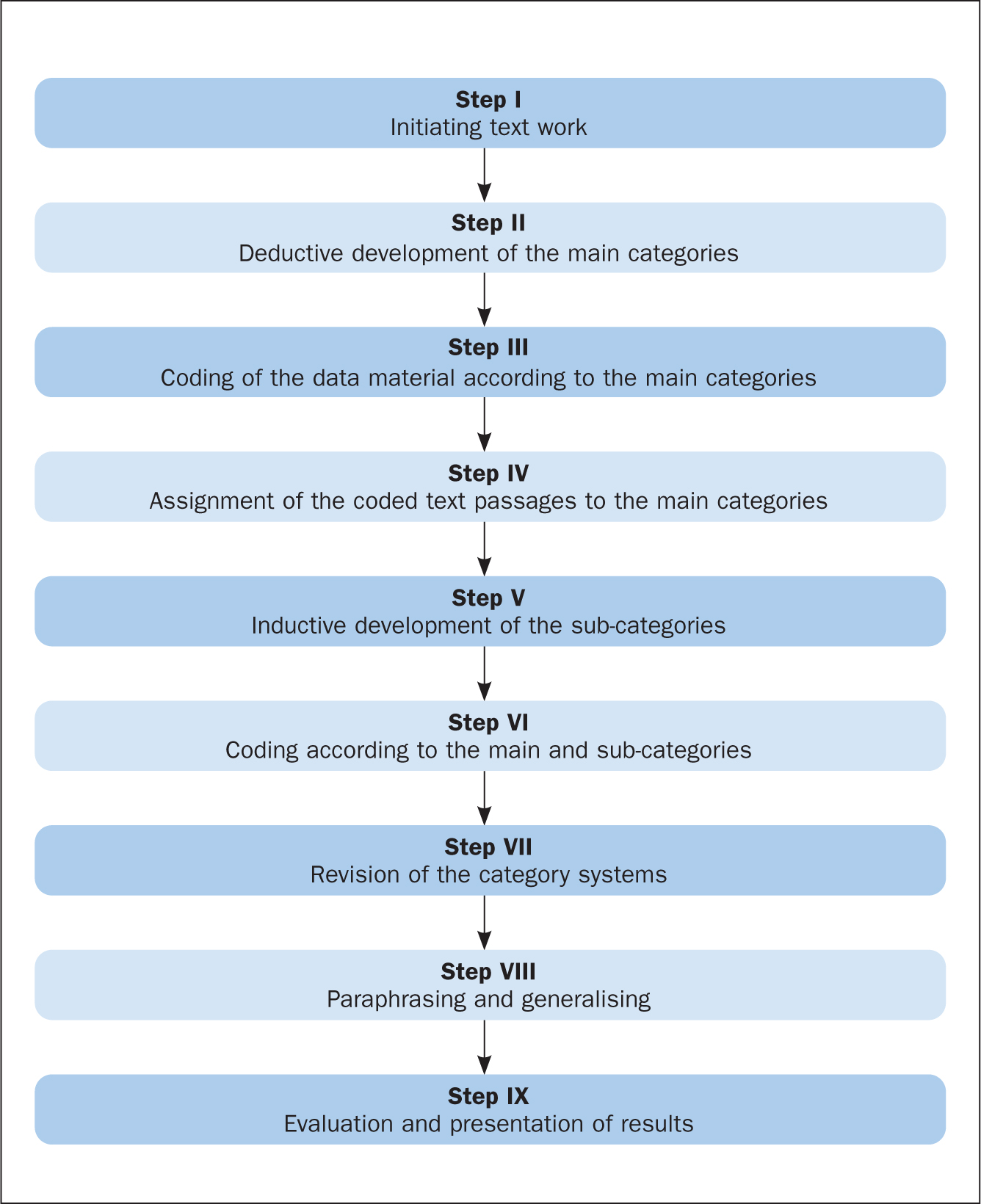

The recorded audio data were transcribed, pseudonymised, anonymised and secured under lock and key. Any information on the transcripts that might identify participants was removed. Following transcription of interviews, a computer-assisted data analysis was undertaken using MAXQDA software. Mayring's (2015) process for qualitative content analysis was selected as the method to structure the content. The focus of interest was to summarise meaningful themes derived from the collected data (inductive) and the elaborated questions of the interview guide (deductive). The steps involved in the analysis were based on the process developed by Mayring (2015) (Figure 1). The same steps were applied to the analysis of all collected data.

Figure 1. The process of content analysis (Mayring, 2015)

Figure 1. The process of content analysis (Mayring, 2015)

Results

The study participants were four women and three men, aged between 23 and 73 years. Table 1 shows a summary of their demographic characteristics.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants

| Participant code | Length of interview (minutes) | Age (years) | Gender | Residence | Education level | Clinical setting | Used electronic devices (hours per day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W5A1 | 25 | 50 | Female | Urban | Degree (university of applied sciences) | Neurology | Smartphone, tablet-PC, computer, TV and radio (4 hours) |

| M7B2 | 40 | 73 | Male | Urban | Degree (university) | Respiratory | Smartphone, computer, radio, TV and camera (3 hours) |

| W6C3 | 37 | 68 | Female | Urban | Degree (university) | Cardiology | Smartphone, computer, laptop, TV and radio (7 hours) |

| M7D4 | 27 | 71 | Male | Urban | Degree (university) | Cardiology and urology | Smartphone, computer, laptop, TV and radio (1 hours) |

| W2E5 | 29 | 23 | Female | Urban | Degree (university) | ENT | Smartphone, Laptop, Computer, Radio and TV (9 hours) |

| W6F6 | 33 | 60 | Female | Rural | Degree (university) | Respiratory | Pushbutton phone and computer (3 hours) |

| M3G7 | 21 | 38 | Male | Urban | Degree (university) | Urology | Smartphone, tablet-PC, Computer, TV and Radio (8 hours) |

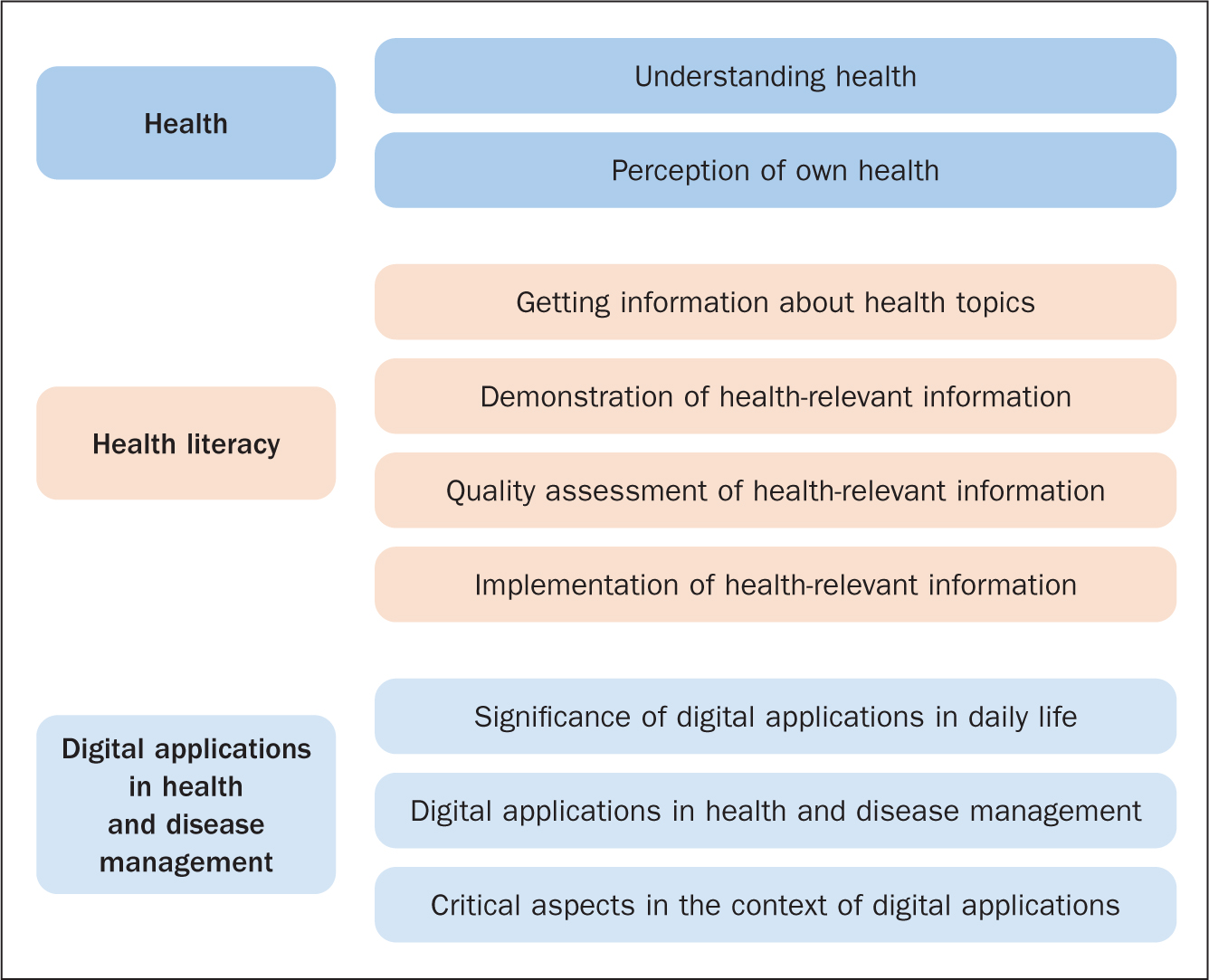

Core statements made by the subjects in response to the research questions were divided into three main categories, and each was subdivided into its own set of themes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Categories and themes identified in the analysis of the interviews

Figure 2. Categories and themes identified in the analysis of the interviews

Understanding health

All participants defined the phenomenon of health in terms of having a balanced metabolism and associated subjectively perceived physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing. In this context, two respondents made references to existing social contacts in challenging times and living independently. In the view of the interviewees, health cannot be measured exclusively in terms of this physical wellbeing, but also includes the individual's emotional state and wellbeing, in addition to the physical and social environments. Four respondents also described health in terms of the number of sick days they had per year or the ability to independently and regularly undertake health-promotion measures such as healthy eating and physical activity.

‘For me, health means not being constantly on sick leave or in a hospital and being able to lead a happy, even peaceful life. […] So, not only with my body, but also all around, for example inner peace, family, friends you can rely on and who help you when you are not doing so well.’

W2E5

Perception of own health

Respondents perceived their physical health to be below optimum at the time of the interview. They used age, diagnosed diseases, necessary therapies and hospital stays as benchmarks. In some cases, patients described the resulting health challenges, as well as the uncertainty surrounding their health status, as a burden.

‘I don't feel healthy. But I don't feel sick either. This in-between feeling healthy and feeling sick is a huge burden.’

M3G7

However, interviewees also described the hospital stay as an opportunity to reflect on their individual health status and to come to terms with periods without symptoms

‘I don't think I actively perceive my health at all, because I've always been healthy until now. […] And now that I'm in hospital and have to wait for the results […] I use this time to reflect on my health status and to think about how I can optimise it.’

M3G7

Getting information about health topics

All subjects reported that they sourced their information on health-related topics from newspapers, magazines, public broadcasting, social media and health online portals or (peer-reviewed) journals, as well as from family and friends who worked in health care:

‘I have a large number of friends who are doctors. That's where we always talk about my aches and pains. Radio and friends, of course, too.’

M7B2

Demonstration of health-relevant information

All participants identified images, video and text-based materials as alternative methods to present health-related information, with a combination of media considered as the most appealing. In this context, it was important to patients for these different components to be well co-ordinated.

‘I don't need artistic pictures that you find in magazines when you read through popular literature in waiting rooms. Some symbolic images … are really awful and don't do you any good.’

W5A1

Participants criticised the fact that there was wide variation in the quality of information in whichever format it was presented, and that it was often difficult for a layperson to accurately assess the validity of health- or disease-related information.

The difficulty is that, if I now research some disease on the internet, I can open 15 different pages with pictures […] and I don't know which one I can trust more.’

W6C3

As a result, participants tended to prefer information that came from Austrian sources because they felt that it was at a level that is internationally recognised as being reliable and high quality, compared with information that they might come across from other countries.

‘I rather trust Austrian sites, because they are from my homeland and our medicine is considered to be good quality.’

W6C3

In addition to expressing doubts about the quality of many sources of information, and the scope and level of what they might find (in terms of textual and visual presentation), participants cited concerns about the time required to research and distinguish trustworthy from doubtful information.

Quality assessment of health-relevant information

All patients stated that they consciously reflected on any information they had read. The level of their reflection depended on how relevant, practical, up-to-date and credible they considered a particular source of information to be. In terms of how practical any advice might be, three respondents noted that they considered information to be of high quality if it was easy to implement in daily life and provided added health value. They expressed similar concerns about how up-to-date any information they encountered might be:

‘It's good if I [can] simply say, “Okay, reading this new article has helped me”. It's no use if someone regurgitates something that has already been published 4 years ago.’

W5A1

Credibility was also cited by patients as one of their quality criterions which they assessed by the amount of advertising that accompanied any information conveyed on broadcast media, such as television and radio. For example, the more advertising that was broadcast on radio or television with the item, the more untrustworthy a programme or channel was perceived to be.

Implementation of health-relevant information

Patients described the implementation of any information they found and deemed credible, for example with regard to health promotion (ie to take more exercise or change diet) as an integral part of having an active and healthy lifestyle. However, the effect of their illness on level of health at the time of interview often presented a major challenge.

‘I would like to do a lot more, but that is not possible at the moment. The immobility restricts me too much.’

W5A1

Other challenges related to a lack of motivation or the time available every day to implement changes, such as increasing their level of exercise. Irrespective of this, all those interviewed agreed that health-promotion measures can contribute to improving individual health and preventing an exacerbation of illness.

In addition, participants reported that negative experiences with illness within the family unit increased their motivation for regular implementation of health-promotion measures:

‘My father died of nicotine and alcohol addiction. […] That's why I try to live healthily.’

M3G7

From this perspective, participants primarily reported making an effort to avoid harmful activities, such as smoking and drinking, as well as placing high value on having a balanced diet. Some patients also placed value on ensuring that food should comply with fair trade obligations—in their view, not only would it be healthier, but it would also have been produced under fair conditions.

‘It should be produced fairly! […] Because nowadays nobody knows what's really in it, and the farmers don't get anything anymore anyway.’

W6F6

Other activities participants implemented after reading the relevant and credible advice included walking, hiking, running, workouts at gyms or spas, day spas, cycling, rock climbing, and dancing as other specific activities, which they felt would contribute to better health.

Significance of digital apps in daily life

Respondents reported that digital apps were of great importance in their everyday lives.

‘Television is the window to the world. But mobile phones, laptops and tablets also serve to expand the horizon of knowledge …’

M7D4

Patients thought that the major benefit offered by digital apps were that they offered information, but also helped to structure everyday activities and to incorporate leisure activities (eg vacation planning) in daily life, provided education and enabled contact with the outside world. The latter was particularly important for people who were unable to independently leave the home setting due to illness, as digital apps helped them participate in social life.

Nevertheless, patients sometimes described the increasing use of apps in their daily lives as forced dependence.

‘I use digital apps throughout the day. Without them, I can't work, communicate with other people, inform myself or do leisure activities. [I] am totally dependent on the technology!’

M3G7

This contrasts with the same patient's statement that frequency of app use cannot be classified as dependency, since digital apps have become an indispensable part of the modern life and are part of human progress:

‘Nowadays, nothing works without digitalisation. This applies not only to care or medicine, but also to work or leisure.’

M3G7

Digital apps in health and disease management

Patients indicated that they used digital apps to support their health and disease management. In addition, apps were seen as enriching and pivotal to enhancing the quality of care provided by Austria's healthcare system, including the use of both health-service branded apps and third-party apps approved by the health service.

‘Digitalisation, especially in health care, medicine and nursing is, in my opinion, the most important strategy for providing people with optimal care. Without it, we might as well call ourselves a third-world country.’

W2E5

The interviewees used the apps to find out about health-promotion measures or information about their own conditions to ensure they were up-to-date with the latest scientific findings. They also used apps to obtain background information on therapeutic options and to help understand medical terminology. Content that was presented as simply and as comprehensibly as possible was favoured. Information obtained by in advance of going into hospital for treatment also gave them a sense of security and offered a way to confirm that the information provided by health professionals was accurate:

‘It … helps you enormously. Also to check whether they [health professionals] are really right about the care or the diagnoses, and so on.’

M7B2

The use of apps to inform oneself before or during a hospital stay was also justified by the fact that staff had no time to provide patient education and extended information on therapies, medication, symptoms or diagnoses. The apps, thus, offered the opportunity to balance out the perceived challenges the patients faced in the clinical setting.

‘I don't know, I just feel safer because I already know what it could be and nowadays, in the hospital, nobody has time to explain anything to me anyway.’

M3G7

Digital apps were also used to internalise other people's experiences of health or illness and to compare them with one's own circumstances.

‘I always look for the one where people have written down their experiences. […] Then I compare these with my own things.’

W6C3

In addition, apps were used to record and document vital signs at regular intervals and, thus, monitor them over a period of time. Respondents also used apps to record and keep track of their health promotion activities.

Critical aspects in the context of digital apps

The most frequent complaint from the interviewees was the lack of quality control of accessible health- or disease-related information. For laypersons, this could lead to them taking advice that could have adverse effects on their health. As an example, one patient expressed the fear that a seriously ill person could be exploited and given false information in the interests of making financial gain.

‘How inhumane, how false and how problematic all this content is that is often conveyed online. Drugs are advertised within apps and then it turns out that everything is ineffective and a lie.’

M7D4

Interviewees also researched information online about their symptoms, often before visiting a doctor, which resulted in them experiencing unnecessary uncertainty.

‘[I] always think to myself that, hopefully, it will be different for me, that I don't have that. I just always research everything too quickly.’

W6C3

The rapid pace of technological progress, which is causing some people to feel anxious that they can no longer keep up, was raised as a further challenge. The relentless speed of widespread digitalisation reinforced this fear among subjects, with the need to be constantly accessible and available to the outside world cited as major concerns. At times, respondents felt they were at the mercy of social media due to a sense of obligation to constantly use digital apps, which in turn resulted in a perceived sense of decreased privacy.

‘I'm now getting into a phase where all this use really ticks me off. Well, I often scold myself and say: “I can't take it anymore! It's having a bad effect on [my] privacy!”’

W6C3

Scepticism with regard to data protection was raised by all interviewees. They made reference to the careless handling of personal data by individuals using apps such as Twitter and Facebook, the perceived automated transmission of locations, and the processing of health- or illness-related data by all apps (both official health service apps and third-party apps), and that this was done ways obscure to a layperson. The latter took on a high priority for respondents in the context of employers and insurance benefit rating.

‘How much do they [health-related apps and as social media apps] know about you, then? What are they allowed to know about you? What disadvantages do they put you at in your job? These are always very sensitive issues.’

W2E5

Discussion

The survey results show that patients reflect deeply on their own state of health within the confines of their individual health literacy and are keen users of digital apps to support their health and disease management. Both individual level of health literacy and patients' use of apps can be seen as opportunities for health professionals, such as nurses, to positively influence patient health care. In particular, nurses can play a role in improving both patients' health literacy and their health and disease management—including signposting them to credible and robust health apps. However, this requires health professionals to adopt suitable strategies that consider known patient factors (such as age, gender, level of education or technology skills) that can affect both health literacy and use of technology, as well as taking into account patients' personal experiences. This is valuable, in that taking individual disease-specific experiences makes easier the implementation of any recommended health-promotion measures (Naidoo and Wills, 2019).

With regard to digital apps, it is recommended that they should be continuously revised to enable them to be tailored to a specific patient group, especially with regard to age- and disease-specific differences in patient responses. Qualitatively generated research results (user experience) have an important role in this context, since personal impressions are essential for developing concepts or apps (Weisel et al, 2020). For different target patient groups, the focus should also be placed on specific communication strategies and confidence-building measures, as these can have a significant effect on the likely acceptance and correct use of any apps. The focus would include, for example, ensuring that educational materials can be adapted to a patient's technical abilities, age and education level (eg choice of words, font size, amount of text, platform), and on providing the contact details of health professionals who can provide individual support (eg telephone, SMS or email details, which should be regularly updated).

It is also important to ensure that patients do not feel that apps are a substitute for face-to-face interaction or that insufficient technical abilities are criteria for exclusion. Where patients lack the technical knowledge, there is a need for intensive exchange, as well as active promotion of individual skills in the context of digital apps. This can be ensured, for example, by offering group training sessions within which users can familiarise themselves with an app in a protected setting and learn about its range of functions. Discussion with experts and other users are an important way to promote the exchange of experiences, opinions, and concerns.

The fact that respondents in this survey sourced their information from different media illustrates the importance of ongoing quality assurance. Any clinical content presented in an app must therefore be reviewed with regard to the rigour, reliability and comprehensibility of the information. In this context, nurses play an important role, as patients can be made aware of how credible particular apps are in the course of any education and counseling sessions. Digitalisation serves, on the one hand, as a way to raise patients' health literacy levels and, on the other, apps offer a valuable tool that can be used as part of counseling and education.

To enable them to support patients in this way, nurses themselves need specific expertise in health literacy and methods of health promotion, accessed through continuous education courses. In this context, a curricular change regarding basic training could also be considered, in the context of this article in Austria, but would apply internationally as well to take greater account of widespread digitalisation and health literacy. This would give nurses the skills to evaluate digital apps in terms of the rigour of information they provide, their practicability and to assess any safety risks relating to data protection, and to recommend trustworthy apps to patients (Zentrum für die Qualität in der Pflege (Centre for Quality Care), 2019; Stadt Wien, 2021).

In addition, there is a need to put in place a clear legal framework for regulating health-related apps and to make nurses aware of how to identify secure and trustworthy apps—in this survey respondents were sceptical that apps ensured adequate data protection. In particular, it is difficult for individuals in need of long-term care who require the support of other people to avoid disclosing sensitive data, but they may have insufficient skills to assess the quality of a particular app. With the increasing use of digital media in clinical settings, it is important to not only draw up a legal framework to regulate apps, but also to ensure regular review of the law to keep up-to-date with developing technologies. Other issues that it is imperative to address are the need for informed patient consent when they are registered on an app by someone else, such as a health professional, as well as the right to privacy, self-determination and social justice.

Limitations

Seven guided in-depth interviews were conducted as part of the data collection. Although the final interview did not generate any new information, it cannot be ruled out that complete data saturation was not reached. Patients might have avoided stating certain things in order not to put themselves in a situation they may have perceived as uncomfortable. All respondents had an academic degree and, since education has been shown to be an influencing factor in health literacy and acceptance of technology, the results must be viewed with that in mind. Cultural or generation-specific differences, if this study were to be repeated in other countries, could also lead to different results. The same applies to age- or setting-specific aspects.

Another factor to consider is that the expense allowance could have posed as a financial motive for participation, although this possibility was discussed in advance with the ethics committee and the study hospital, and no objections were raised by either.

Furthermore, the broadly formulated inclusion and exclusion criteria may have had a detrimental effect on the specificity of findings. Nonetheless, these were explained by the responsible ethics committee as a prerequisite for a positive ethics approval and justified with the fact that the scope of information on an insufficiently researched area would increase if the inclusion and exclusion criteria were formulated more broadly. It should be noted that the present study was carried out as part of a master's degree of one of the author's (MK) and, hence, there was a relationship with the ethics committee, in that ethics approval was the basis for completing the degree.

Conclusion

The results show that the perceived health literacy of respondents is an import factor in their daily life. The situation is similar for the use of digital apps for health- and disease management. To maintain health or promote the recovery process, health-promotion activities are independently implemented. In this context, patients described apps as suitable tools to promote health literacy. Challenges in the context of health literacy arise, among other things, from the existing abundance of information. With regard to the use of apps, patients expressed scepticism regarding the handling of sensitive data or the possibility of publishing unfiltered information.

There is a need for additional qualitative studies to examine in more detail patients' health literacy levels and the benefits of digital apps in health and disease management. Individual patient experiences make an important contribution to supplement quantitative findings.

The findings of the study show that patients already access different media for information, including apps, but require help with identifying robust and credible resources. Health professionals, including nurses, can therefore play a key role in ensuring that patients have adequate health literacy skills and supporting them by signposting to, and educating them how to identify, credible and trustworthy information and apps to support health and disease management.

KEY POINTS

- An international comparison showed that 54.8% of the Austrian population has below-average health literacy skills

- No studies have been published so far in Austria on the health literacy of patients in relation to the use of digital apps that aim to support health and disease management

- Patients indicated that they used apps for both health and disease management

- All participants have raised concerns about data protection

CPD reflective questions

- What part do nurses play in the use of digital apps for patients in health and disease management?

- What opportunities does the existing acceptance of digital apps by patients hold for nursing care in the future?

- How can nurses critically assess the robustness and trustworthiness of apps?