Birth-Aid is a charity established by a team of urogynaecologists from the Warrell Unit, Saint Mary's Hospital, Manchester in April 2016 (http://www.birth-aid.org.uk/). The charity helps women with childbirth injuries by providing surgical treatment and training for local health professionals in the prevention and treatment of future birth injuries. Before formal registration of the charity, teams of consultants and junior doctors from gynaecology, obstetrics, neonatal medicine and colorectal surgery had been holding two surgical camps a year at Holy Family Virika Hospital in Uganda for the previous 3 years, and this pattern has continued (with a pause due to COVID-19).

Background

Uganda is located within the central east of Africa and had a population of over 39 million in 2017 (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2021). Despite significant improvements reducing the level of poverty in Uganda, 20% of Ugandans live below the national poverty line, with 35% of the population living on US$1.90 or less per person per day (World Bank, 2016). Total annual expenditure on health per person is US$43 compared with US$4315 in the UK (World Health Organization (WHO), 2021). There is a high fertility rate (IHME, 2021) coupled with delayed or limited access to emergency obstetric care, for geographical, financial or cultural reasons (Kyei-Nimakoh et al, 2017). Data are limited regarding the prevalence of birth injuries such as obstetric fistula and obstetric anal sphincter injuries in Uganda, as with many low-income countries (Tunçalp et al, 2015). However, the causative factors behind birth injuries, such as delayed or limited access to antenatal or emergency obstetric care and unsupervised deliveries, correlate with increased maternal mortality (Browning and Patel, 2004; Wall et al, 2005). In fact, it is estimated that for each maternal death, 30 women will suffer ‘injuries, infection and disabilities’.

Women in Uganda are around 50 times more at risk of maternal mortality than women in the UK (WHO Global Health Observatory, 2019). Therefore, they are also likely to be at significantly higher risk of birth injuries. A 2011 survey of women in sub-Saharan Africa estimated a 2% prevalence of obstetric fistula in Uganda (Tunçalp et al, 2015), which was more than double the rate of every other country. Obstetric fistula is only one example of a birth injury women in Uganda may experience, therefore the number of women living with any type of birth injury in Uganda is likely to be higher than many other countries.

Birth injuries are extremely debilitating wherever a woman lives; however, for many women in Uganda living without access to running water or electricity (World Bank, 2016) and its resulting impact on maintaining hygiene, life can be very hard. Some women report rejection by their spouse, family or local community (Krause et al, 2014; Barageine et al, 2015). Before each camp, a call is put out across local radio inviting women with birth injuries to attend the hospital for assessment and, if indicated, free treatment. Around 100 women attend for assessment at each of the week-long camps with the most common birth injuries being obstetric fistula, historic unrepaired third or fourth degree anal sphincter injuries and vaginal prolapse.

In 2016, the Birth-Aid team invited us, as nurses, to support one of the surgical camps. As this was the first time UK nurses had collaborated in this way, the responsibility of representing our profession was at the forefront of our minds. Having never previously been to Uganda, or indeed to any African country, we weren't really sure what to expect. Both of us have gynaecological nursing backgrounds; however, Pam also has a wealth of experience in management, audit, education and service improvement and Lucy had previously worked in research so we hoped that between us we would have the required skills and knowledge to contribute positively to the camp. We were asked to undertake a scoping exercise to determine the role that nurses could undertake in future camps and therefore the plan for our first visit was to observe and listen to the local team's needs.

First impressions

After a lengthy journey from Manchester to Fort Portal we arrived at Virika Hospital on the Monday morning excited to meet the local team and get to work. Virika Hospital, in Fort Portal, Western Uganda, is a private not-for-profit hospital with inpatient, outpatient and theatre services. The maternity and gynaecology ward where camp patients were cared for consists of 43 beds including three for labouring women. The ward was staffed by both nurses and midwives, many being dual qualified. During our visit there was approximately one delivery every 24 hours. The local nursing and midwifery role focused on delivering babies, breastfeeding support, medication administration, stock replenishment including medication and transferring patients to and from theatre, which took two nurses as there were no portering staff. Personal care, nutrition and hydration needs were provided by a ‘caregiver’ such as a friend or family member who stayed at the hospital alongside the patient, sleeping outside overnight. Patients were required to bring their own bedding and food and have someone fetch water for them from the hospital pump. The local staff work in challenging conditions. The hospital rarely has free-flowing water; therefore water is pumped and left in jugs by the sinks to facilitate handwashing. At times the electricity cuts out and although there is an emergency generator, it takes some time to come online and on one visit Lucy saw a baby being delivered by caesarean section in the dark after the power cut out mid-procedure. The team have developed innovative ways to work given their resources, such as developing X-rays in the sun and drying linens outside as far as the weather allows.

Virika hospital

Virika hospital

The first day was extremely busy. Women were assessed and triaged ahead of admission for surgery, to be seen by a local doctor if symptoms were unrelated to birth injuries or offered conservative management options such as a support pessary or pelvic floor muscle exercise training if a prolapse was not significant or if a woman had not completed her family. This provided some emotional challenges we had not experienced at home. Women attended with obvious cervical malignancies that neither the team nor the hospital could deal with and women were unable to access treatment elsewhere due to financial restrictions or other logistical healthcare barriers. One woman attended alongside her husband and young baby with a diagnosed perineal tear. She had been seen at a different local hospital where she'd been assessed and diagnosed with syphilis; unable to pay for treatment, she had waited for the camp. The cost of antibiotics to treat the whole family was less than £10 but when the team offered to pay for treatment, we discovered the hospital pharmacy did not stock the required medicine. Fortunately we managed to procure the treatment externally; however, this demonstrates that access to medicines is one of the barriers to health care that people living in Uganda may face.

Improving patient safety

After our return from Uganda, Pam wrote a detailed summary of our experience from a nursing perspective and we decided on a number of actions that we wanted to implement for future camps. We were mindful that we didn't want to enforce our ways of working on our colleagues at Virika, as well as understanding the extensive differences in resources and equipment between what we were used to and what was available at the hospital. Even so, there were actions that we felt were both realistic and necessary to ensure safe and effective provision of quality care for women having surgery as part of the camp. We hoped some aspects of care would be adopted by the local nursing and midwifery team throughout the remainder of the year.

The maternity and gynaecology wards at Virika Hospital

The maternity and gynaecology wards at Virika Hospital

On our next visit we focused on patient safety. Identifying and locating patients was an issue both for the Birth-Aid team and local colleagues, who were not used to having such a large volume of patients admitted at the same time. The women were distributed across the hospital on several wards. We decided to create a patient board and introduce name bands for all camp patients. The patient board was a simple laminated sheet of A0 card with a grid marked on it to record details such as name, bed number and camp identification number. Due to some initial organisational issues regarding missing patient case notes we used two different coloured name bands: a white one with the patient's identifying details on and a red one with the procedure written on after surgery so that we could easily identify what procedure they had should the case notes go missing.

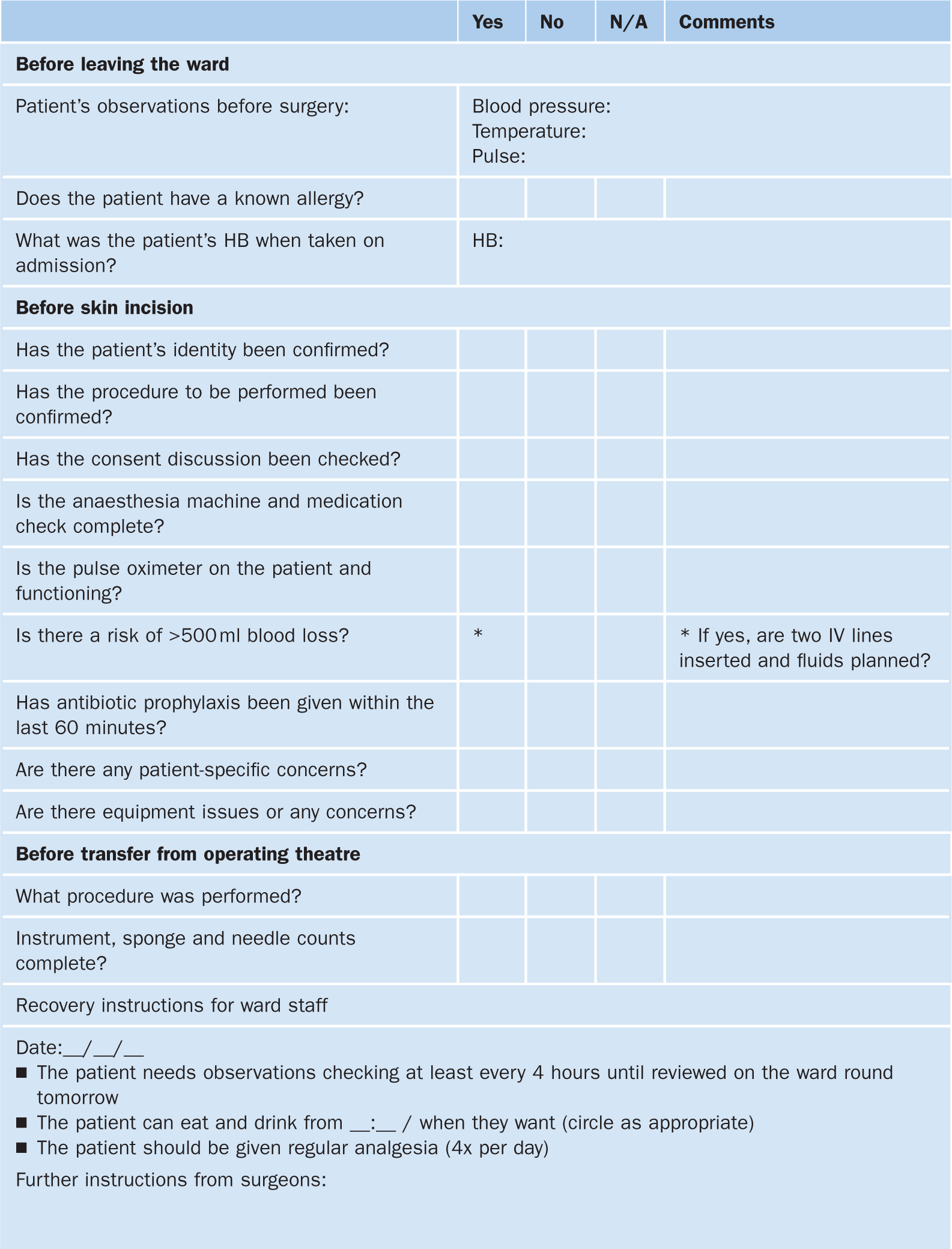

We also introduced a modified version of the WHO Safe Surgery Checklist (WHO, 2009) to ensure that it was suitable for the setting at Virika Hospital and included additional checks to ensure informed consent and clear communication with ward staff following the procedure (Figure 1). After spending time on the wards, we shared concerns about the infrequency of postoperative observations. Although conscious we shouldn't expect this to mirror UK practice, we worked with our surgical colleagues to decide the minimum frequency of observations that could safely be performed for postoperative camp patients. We then created educational sessions to teach nursing and midwifery colleagues the importance of measuring each observation. Pam procured and distributed a large number of fob watches. These proved extremely popular and provided nurses with the ability to record time, pulse and respiratory rate without having to search for the sole ward clock. During a brief visit to the operating theatre suite—which consists of two theatres with one operating table in one and two in the other, separated by a simple medical privacy screen—we were concerned for staff wellbeing due to a lack of equipment to facilitate safe manual handling. Following this we spent time teaching staff to use slide sheets and work as a team to transfer a patient.

Figure 1. Modified surgical safety checklist for use at the hospital (HB=haemoglobin level)

Figure 1. Modified surgical safety checklist for use at the hospital (HB=haemoglobin level)  Operating theatre

Operating theatre  Patient wristbands: simple but effective

Patient wristbands: simple but effective

As a team, Birth-Aid colleagues agreed on the importance of positive role modelling particularly with emphasis on the previously described new introductions to practice. While on the ward, with the permission and support of Sister Mary Magadelane, the local team's matron, we would not allow patients to be transferred to theatre until they had a preoperative set of observations performed and the checklist was complete. Barriers to recording observations such as the lack of a clock to measure pulse and respiration rate were mitigated by provision of fob watches to clinical staff. We also discussed with ward staff the importance of preoperative observation and haemoglobin checks to ensure the patient was healthy before surgery. Instances of hypertensive and anaemic women being identified during completion of the preoperative checklist, and subsequently optimised before they went for surgery, demonstrated the benefit of checklist completion to local staff. On arrival in theatre, Birth-Aid surgeons emphasised the importance of completing the checklist before surgery. Following surgery, patients were not transferred without following safe manual-handling procedures.

Since our first visit in May 2016, there has been nursing input for each of the eight subsequent Birth-Aid camps. This ensures the changes we have introduced are consistently followed during each visit. We hope that practices we have introduced, such as use of a patient board, safe surgery checklist and improved manual handling procedures, are viewed as beneficial and followed by staff between camps and have left the necessary resources at the hospital. However, other than providing the necessary equipment, demonstrating how it should be used and explaining the benefits while working alongside the team during a camp, we recognise it is not our place to enforce changes on the team outside of ensuring the patients cared for during our camps receive safe, high-quality care.

Reciprocal learning

Nurses have become an essential part of the Birth-Aid team ensuring women receive high-quality and safe care as well as enabling the surgeons to work as efficiently as possible. Moreover, the Birth-Aid nurses have supported the local nursing team by delivering educational sessions focusing on essentials such as observations, nutrition, hydration, different urogynaecological procedures and pelvic floor muscle exercises. Some of the local nurses and midwives expressed surprise at the autonomous role that we performed, working alongside the doctors rather than for them. We hope that demonstrating the different roles both professions have in working together to provide high-quality patient care will begin to counter the perception of some that the nurse is a doctor's handmaid. We really enjoyed working with the staff at Virika, particularly the nursing staff who seemed to value working alongside nurses from another country. We took our uniforms to show the local nurses how we looked working in the UK. Nursing caps are important in Uganda as they demonstrate the level of training and experience a nurse has, therefore the nurses at Virika Hospital were surprised that we didn't have one and very kindly commissioned the hospital tailor to make one for each of us, which we both treasure.

Lucy and Pam with our new nursing caps and our driver, Bosco (photo taken in 2016)

Lucy and Pam with our new nursing caps and our driver, Bosco (photo taken in 2016)

The people living in Uganda were unbelievably kind and welcoming. The overwhelming generosity and happiness of every person we met, despite most having so little, was extremely moving and will stay with us for the rest of our lives. We both strongly believe that this experience of sharing knowledge and skills with colleagues in Virika has been reciprocal: we also learned much from the patients and staff at the hospital. Yeomans et al (2017) found that UK doctors volunteering overseas reported improved skills related to leadership, communication, teaching and cultural awareness 6 months after the experience. Another literature review identified improvements in skills and knowledge following volunteering abroad including clinical, managerial, communication and team working, patient experience and dignity, service development and academia (Jones et al, 2013). Developing these skills and furthering knowledge of NHS workers while volunteering abroad therefore appears to benefit the NHS as well as those elsewhere.

Our colleagues at Virika work in a remote, resource-poor setting and yet still provide care and compassion to their patients. The resourcefulness and creativity of the doctors, nurses and midwives is a learning opportunity for us all.