Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic haematological disorder characterised by deformations in red blood cells, causing them to cluster and form blockages in blood vessels (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021). This results in severe pain, known as a sickle cell crisis, and in severe cases leads to organ damage. The disease affects around 14 000 people in the UK (Dormandy et al, 2018; NICE, 2021) and is the most prevalent inherited condition in the UK (Public Health England, 2022). Despite this, patients with SCD face substantial health inequalities and poor health outcomes (Piel et al, 2023), which have been attributed to the fact that the majority of patients with SCD are of Black African and Black Caribbean descent (All Party Parliamentary Group on Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia (SCTAPPG) and The Sickle Cell Society, 2021). Therefore, there is a significant need to improve the treatment pathways for patients with SCD.

Patients with SCD require frequent venous access to undergo exchange transfusions, which replace blood containing sickle cells with donor blood (NICE, 2021). Over time, this frequent access causes scar tissue and damage to vessel health, leading to many patients being classed as having difficult intravenous access (DIVA). In DIVA patients, the use of peripheral intravenous cannulas (PIVCs) often results in unacceptably high failure rates and multiple, often painful, insertion attempts (Bahl et al, 2020).

At the author's Trust, Homerton Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust in East London, the age range of patients on the exchange transfusion programme is 18 to 55 years. Ethnicities are West African and Caribbean. Femoral lines (GamCath Haemodialysis Pack, Gambro) were used for patients with SCD who had DIVA to ensure that they received their planned treatment every 4 to 8 weeks, depending on their individual protocol. However, femoral lines have their own challenges, including increased risk of complications for patients, such as arterial puncture, haematoma, increased risk of skin infection at the puncture site, plus a higher risk of healthcare-associated bacteraemia (or catheter-related blood stream infection). There are also increased staffing and equipment needs (Kornbau et al, 2015; Castro et al, 2023). Once the femoral site develops scar tissue, this procedure becomes increasingly complex and often requires theatre admission, which requires more staffing and time at best, and delayed clinical treatment at worst.

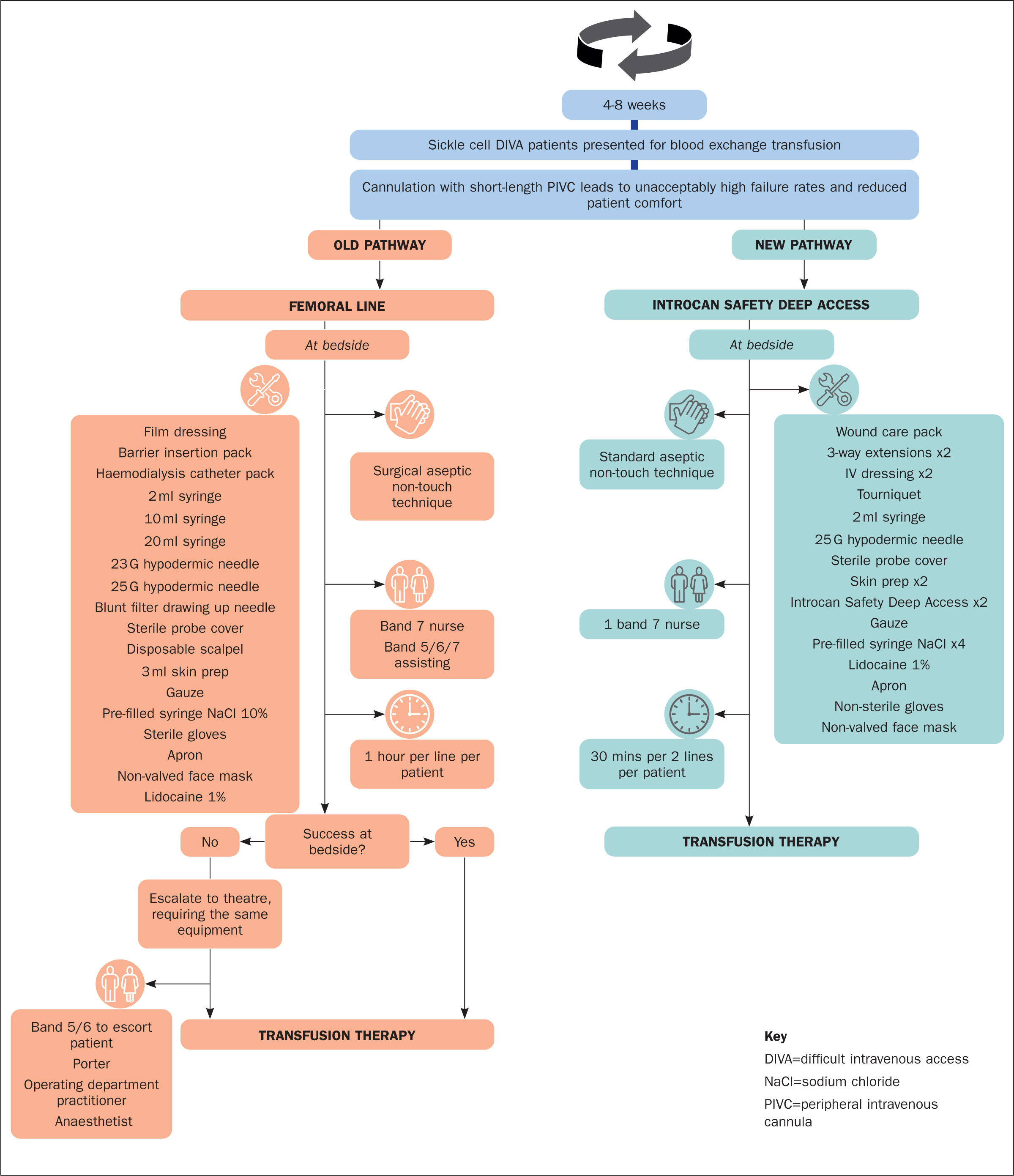

To overcome the challenges of femoral lines, in June 2020 a new pathway was introduced for all patients with SCD who have DIVA and were on the exchange programme, which involves placing two long peripheral catheters (LPCs) (Introcan Safety Deep Access (64 mm), B Braun Medical UK) under ultrasound guidance in the upper arms. The length of the LPC enables increased purchase in the vein, while ultrasound guidance ensures accurate placement of the LPC, avoiding scar tissue. Across all the gauge sizes that are used, the length is 64 mm, which enables the practitioner to select the smallest gauge size appropriate to promote adequate haemodilution.

Methods

An observational audit was conducted to understand the value in terms of value for money and clinical time spent of the new LPC pathway. Data collection began in November 2021 for 1 year. The equipment and staffing required to undertake a femoral line insertion and an LPC insertion were detailed by the medical day unit staff and the Vascular Access Clinical Nurse Specialist, and associated costs were obtained from the Trust's Procurement Department. Staffing costs were derived from the Personal and Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) at the University of Kent for the year the audit was undertaken (Jones and Burns, 2021).

When the new pathway was introduced, the band 7 Vascular Access Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) inserted the LPCs, as part of the quality improvement project. As it became common practice, training was extended to the band 7 Haematology CNSs and band 6 nurses on the unit. Training involved an eLearning module followed by practical teaching sessions using a phantom. Once staff were confident in their use of ultrasound and needling the phantom, they progressed to supervised practice with patients deemed to have ‘easier’ veins. They continued to be supervised until they were competent.

In addition, a sample of three patients with SCD who had experienced both methods of cannulation for their exchange transfusions were asked to provide written feedback about their experience in answer to three questions. Inclusion criteria were SCD and DIVA, and being on the exchange transfusion programme. Only three patients took part because of limited time and clinical resources, but all three had experienced problems with femoral line placement and were at risk of being removed from the exchange transfusion programme. They were therefore placed on the LPC programme at an early stage. It was thought that they would have insight into both procedures. The three questions were:

- Can you tell me about your experience of having a femoral line placed in your groin; how did it make you feel?

- Can you tell me about your experience of having two long peripheral catheters placed (one on each upper arm); how did it make you feel?

- Which did you prefer and why?

Patients' written consent to use their comments was obtained. The Trust's research and development department was approached for approval of this quality improvement project, and it was approved in line with Health Research Authority guidelines (2023).

Results

The required equipment for a femoral line insertion totalled £80.48, compared with £19.31 for two LPC insertions, a saving of £61.17 or 76% (Table 1). The LPC also required only one Band 7 nurse to insert, compared with two nurses (including a Band 5, 6 or 7 to assist) for a femoral line, and the insertion procedure took half the time (30 minutes instead of 1 hour) (Figure 1). This resulted in a nursing-time cost of £33 for an LPC compared with £121 for a femoral line, a saving of £88 or 73% (Table 1). Therefore, accounting for both consumable spend and nursing-time burden, the new pathway represented a saving of £149.17 per insertion.

Table 1. Consumables and staffing costs for femoral line and long peripheral catheter insertion procedures

| Item | Femoral line | Longer-length PIVC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost per unit (£) | Number of units per procedure | Total cost (£) | Cost per unit (£) | Number of units per procedure | Total cost (£) | |

| Haemodialysis catheter pack | 57.60 | 1 | 57.60 | |||

| Barrier pack | 14.45 | 1 | 14.45 | |||

| Long peripheral catheter 20 G | 5.50 | 2 | 11.00 | |||

| 3-way extensions | 1.35 | 2 | 2.70 | |||

| 3 ml skin prep | 0.97 | 2 | 1.94 | 0.97 | 2 | 1.94 |

| 10 ml pre-filled saline syringe (externally sterile) | 0.48 | 4 | 1.92 | |||

| Sterile gloves | 0.66 | 2 | 1.32 | |||

| Sterile probe cover | 1.28 | 1 | 1.28 | 1.28 | 1 | 1.28 |

| 10 ml pre-filled saline syringe (internally sterile) | 0.21 | 4 | 0.84 | |||

| Wound care pack | 0.48 | 1 | 0.48 | |||

| 10 ml syringe | 0.44 | 1 | 0.44 | |||

| Film dressing | 0.21 | 2 | 0.42 | |||

| Transparent dressing | 0.15 | 2 | 0.30 | |||

| Lidocaine 1% | 0.30 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 1 | 0.30 |

| Disposable scalpel | 0.24 | 1 | 0.24 | |||

| Tourniquet | 0.19 | 1 | 0.19 | |||

| 10 ml syringe | 0.08 | 2 | 0.16 | |||

| Gauze | 0.02 | 6 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 25 G hypodermic needle | 0.08 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 1 | 0.08 |

| 23 G hypodermic needle | 0.08 | 1 | 0.08 | |||

| Non-valved face mask | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 |

| Non-sterile gloves | 0.07 | 1 | 0.07 | |||

| 2 ml syringe | 0.02 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.02 |

| 18 G blunt filter drawing up needle | 0.02 | 1 | 0.02 | |||

| Apron | 0.22 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Subtotal consumables | 30 | 80.48 | 22 | 19.31 | ||

| Band 7 nurse (hourly) | 66.00 | 1 | 66.00 | 66.00 | 0.5 | 33.00 |

| Band 5/6/7* nurse to assist (hourly) | 55.00 | 1 | 55.00 | |||

| Subtotal staffing | 2 | 121.00 | 0.5 | 33.00 | ||

| Total cost | 201.48 | 52.31 | ||||

The average frequency of exchange transfusions for patients with SCD in the Trust is every 6 weeks (8.6 per year); therefore, the average cost saving is projected to be £1 282.86 (£526.06 for equipment and £762.67 for nursing time) per patient per year. There are around 70 patients with SCD undergoing exchange transfusions in the Trust, meaning this saving would amount to £89 800 per year, and 903 nursing hours per year.

Written feedback on the new LPCs was provided by three patients, and was largely positive.

Question 1. Can you tell me about your experience of having a femoral line placed in your groin, how did it make you feel?

‘That's one of the most uncomfortable and painful procedures I had to go through, it was making me very anxious and stressed to have it. I didn't like it at all, plus the anaesthetic wasn't sufficient enough for me to not feel the pain, but I needed it to get better so I accepted it.’

Patient 1

‘When receiving the femoral line I would always feel very anxious before the line was even inserted. As I was awake for the procedures only receiving local [anaesthetic] which on some occasions didn't numb the whole area and caused excruciating pain. But even when the area was completely numb it would still cause me some discomfort as over time of having many lines fitted the scar tissue build up was becoming too much to avoid so even the feeling of having a doctor push and pull through scar tissue that you can in some strange way feel and hear rip was extremely eerie and disturbing and created the anxiety for future line insertion. And the pain once the anaesthetic wore off was immense.’

Patient 2

‘… As time went on I started getting scar tissue, which made it difficult to put the line in or there were times when I couldn't do the exchange. Once it was taken out I had to be very careful because a couple of times it bled once I got home.’

Patient 3

Question 2. Can you tell me about your experience of having two long peripheral catheters placed (one on each upper arm), how did it make you feel?

‘If I knew that this procedure was existing I would have asked for it straight away, it is much better than femoral … Overall, I'm feeling much better off having this procedure and more importantly less stressed and anxious …’

Patient 1

‘The first time I received 2 [LPCs] fitted to be able to receive my exchange transfusion made me feel extremely frustrated at why I had to go through all that pain, stress, and discomfort of having femoral lines fitted to be able to receive my exchanges. It was that easy and painless in comparison … I felt extremely relieved and happy that this was the new way I would be receiving my blood in future, as there was talk that if we couldn't get access via femoral line any longer I would have to be taken off the exchange programme and that of course would put my health in jeopardy.’

Patient 2

‘It's quite uncomfortable because I can't lay down how I want and the nurses need you to be in certain positions that can be quite difficult when you're in pain but apart from that I prefer this procedure.’

Patient 3

Question 3. Which did you prefer and why?

‘Without hesitation [LPCs] as it is less painful, less stressful for my body, and if it is done by someone who knows what she/he is doing then it makes me confident enough to think that I'll have my treatment done in a nice way without too much pain or none.’

Patient 1

‘… Of course I prefer to have the [LPCs] as it [is] less trauma on my body and a far easier experience all together.’

Patient 2

‘I prefer both of them for different reasons. I prefer the femoral line because it allows me to move around the way I want to. The [longer-length PIVCs] are an easier procedure which makes me more relaxed and [there is] a less difficult healing time.’

Patient 3

Discussion

At the author's Trust, the new LPC pathway requires less equipment (22 consumables per insertion compared with 30, Table 1) such as multiple hypodermic needles, sterile gloves and scalpels) than the femoral line pathway. This reduces costs by 76%, and substantially reduces the amount of waste produced by each insertion procedure, supporting national NHS initiatives to become net zero by 2040 (NHS England, 2022). Moreover, the projected cost saving does not account for additional costs that are incurred in the event of the need for theatre admission for femoral line insertion. Therefore, the true cost saving is likely to be much higher.

The new pathway additionally reduces the burden on nursing time, at a time of national staffing shortages across the NHS. The nursing time released by the new pathway can be redirected to other nursing duties, reducing pressure on staff. The reduction in cannulation-associated complications greatly reduces the risk of escalation to theatres, which not only is crucial in supporting the wider elective surgery backlog recovery post-pandemic, but also reduces the risk of delayed treatment for patients with SCD, who are at greater risk of sickle cell crisis and other complications when their exchange transfusion is delayed (Novelli and Gladwin, 2016).

If an LPC fails at insertion or mid-exchange transfusion, a new line is placed; however, this is a rare event. If it was not possible to place a new line to complete the exchange transfusion, then it would be rescheduled with the Vascular Access CNS. Importantly, patient feedback revealed that the LPCs are preferred over femoral lines, causing less pain and anxiety for patients. Patients with SCD experience reduced health-related quality of life (Dampier et al, 2011; Anie et al, 2012); therefore, developing a new cannulation pathway for their exchange transfusions can improve their experience. Use of the LPCs is now part of usual practice with DIVA patients at the Trust.

Limitations

This was a small study in a limited type of patient, but may be of interest to other units caring for SCD patients; results cannot be generalised without further research.

Conclusion

The new pathway forms part of an ongoing process to reduce inefficiencies while improving patient experience, and further auditing will be undertaken to continuously monitor efficiency improvements. Another audit examining how many LPCs have failed and the effect on treatment, and any other complications that may have arisen, is planned.

KEY POINTS

- Long peripheral catheters (LPCs) require less nursing time and fewer device ancillaries to insert than femoral lines

- Patients with sickle cell disease in this quality improvement project experienced less pain and anxiety on insertion of LPCs than femoral lines

- LPCs lead to fewer complications, causing treatment disruption, than femoral lines

CPD reflective questions

- Do you have patients with difficult intravenous access? How are they currently managed?

- Are there ways in which you could improve the treatment experience for your patients with sickle cell disease?

- Could using long peripheral catheters improve your patients' experience?