Lymphomas accounted for 5% of new UK cancer diagnoses in 2017, with cases split between Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) (1%) (Cancer Research UK (CRUK), 2021a) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) (4%) (CRUK, 2021b). This article seeks to compare and contrast the two diseases, showing the characteristics of each, including the significant similarities and the crucial differences in presentation, treatment and survival.

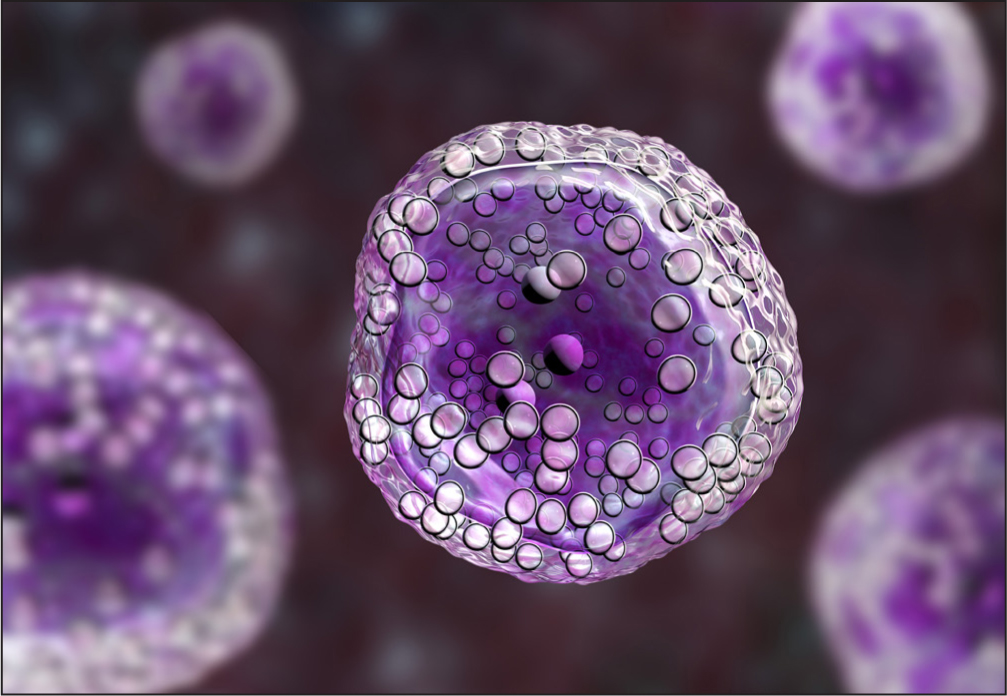

Hodgkin lymphoma has four classified subtypes and is diagnosed by the confirmed presence of Reed-Sternberg cells (Moffitt Cancer Centre, 2018)). Küppers and Hansmann (2005) described these cells as large, multinucleated cells with strange morphology and a phenotype that does not represent any normal body tissue (Figure 1). This disease originates only from the B lymphocyte cells and its four subtypes include (DeVita et al, 2015):

- Classic

- Nodular

- Lymphocyte depleted

- Lymphocyte rich.

Figure 1. All four types of Hodgkin lymphoma are characterised by the presence of giant B lymphocyte Reed-Sternberg cells

Although the lymphocyte-depleted subtype carries a poorer prognosis (Klimm et al, 2011), the subtyping has little influence on presentation or treatment planning (Table 1). A separate subtype, nodular lymphocyte, which is predominant in HL, is a rare diagnosis representing only 5% of HL cases (Ahmadzadeh et al, 2014); it is treated differently, often with ‘watch and wait’ monitoring and only localised radiotherapy, if required (Lymphoma Action, 2021a). The remit of this article does not include further consideration of this subtype.

Table 1. Characteristics of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma

| Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at presentation | Third decade | 55 years + |

| Presenting symptoms | Weight loss, reduced ability to fight infection, unexpected bruising or bleeding, palpable lymphadenopathy, ‘B symptoms’ | As HL |

| Diagnosis |

|

|

| Subtypes | 4 | More than 60 |

| Treatment | First line: ABVD combination chemotherapy regimen, plus consolidation radiotherapy, if indicated. ABVD stands for initials of the drugs used in treatment (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2021a)Second line: induction chemotherapy/allogenic stem-cell transplant or targeted therapies | First line: CHOP/CVP combination drug therapy (+/- monoclonal antibody), plus consolidation radiotherapy, if indicated. CHOP/CVP stands for the initials of the drugs used in treatment (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2021b; 2021c)Second line: a growing number of treatment options, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy determined by remission time, aggression on relapse and patient fitness |

| Prognosis | A 10-year survival rate of 75%, with many patients cured for life | A 5-year survival rate of 50–70%, dependent on stage |

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma by contrast has 60 different classified subtypes, including follicular, mantle cell and Burkitt lymphoma (DeVita et al, 2015) (Figure 2). These subtypes can be categorised into two groups: aggressive (60%) and indolent (40%). Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of indolent NHL, comprising 85% of aggressive and follicular lymphomas (Leukaemia and Lymphoma Society, 2021). DeVita et al (2015) indicated that these subtypes are diagnosed on their morphology, but also by protein antigens present on the cell surface, including CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8 (T-cell proteins) and CD10, CD19 and CD20 (B-cell proteins). B-cell lymphomas represent 90% of NHLs, with the remaining 10% originating from T cells (Leukaemia and Lymphoma Society, 2021).

Figure 2. Burkitt lymphoma is a rare, but aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Figure 2. Burkitt lymphoma is a rare, but aggressive type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The subtype of NHL is more influential on the patient's treatment and prognosis (Table 1).

The patient population: who is at risk

There is no recent data for the UK, but in the USA the median age of patients diagnosed with HL is 39 years (American Cancer Society, 2018), with a male to female presentation of 59% to 41% respectively (CRUK, 2021c). Previous infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a recognised risk factor for HL—it is thought that this is because the damage done to cell material during an EBV infection (diagnosed or silent) can leave pre-cancerous changes. At present, in the UK there is no NHS provision to screen for EBV before, during or following a lymphoma diagnosis.

The incidence of NHL incidence rises steadily from 45 years, with steep rise seen in those aged 55-59 years and again in those aged 80 and over (CRUK, 2021d). A calculation based on CRUK incidence data for 2015-2017 shows that patients with HL represent 13% of the total number of individuals diagnosed with HL/NHL (CRUK, 2021a; 2021b). Risk factors for developing NHL include EBV, HIV, Helicobacter pylori and prolonged use of immunosuppressant medication following solid organ transplant (National Cancer Institute, 2015).

A patient's age at diagnosis is also a relevant prognostic indicator for these diseases. Older patients with HL tend to respond less well to treatment and experience a less deep remission and a more aggressive disease on relapse.

Diagnosis and staging

A universal principle in predicting the outcome of a cancer is that the earlier a diagnosis is made the better the prognosis. Both these disease profiles conform to this principle and it is at diagnosis that the first main similarities between the two are observed. De Vita et al's (2016) list of presenting symptoms specific to lymphomas are grouped under the umbrella term ‘B symptoms’, with or without the presence of a palpable lump, which are:

- Fever

- Weight loss

- Night sweats.

The presence of B symptoms, as defined by Lymphoma Action (2021a), suggests the likelihood of a worse prognosis in both patient groups compared with those presenting with a palpable lump or pain caused by an internal mass in isolation. Other presenting symptoms of the lymphoma patient are less well defined, and may include indigestion, pain, repeated infection, unexpected bruising or bleeding. Although not specific to lymphoma, if a patient who had been previously well presents with these symptoms, it should be sufficient to raise suspicion of a malignant diagnosis.

Both patient HL and NHL groups are diagnosed by lymph node biopsy, followed by a further biopsy of bone marrow, to confirm a positive diagnosis. Lymph node biopsy may require a general anaesthetic, depending on the accessibility of the mass (NHS website, 2020). Radiological imaging is used to establish the extent of disease, most commonly, initially by CT scan, followed by a PET scan.

The disease is staged using the Ann Arbor system (Shankland et at, 2012) (Table 2). The patient will be diagnosed with disease stage I-IV (1-4), depending on the number and location of lymph nodes and other structures involved at diagnosis and then designated as A/B, depending on the absence or presence of other symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2. The Ann Arbor staging system

| Stage I | Involvement of a single lymph node region or of a single extra organ or site |

| Stage II: | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm or localised involvement of an extra lymphatic organ or site |

| Stage III | Involvement of lymph node regions or structures on both sides of the diaphragm |

| Stage IV | Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extra lymphatic organs or tissues with either:

|

| Additional substaging variables include |

|

Sources: Carbone et al, 1971; Lister et al, 1979

When making a diagnosis, the notable difference in characteristics between the two lymphomas is in the pattern of disease sites. HL is typically located in the lymph tissue of the upper body, neck, chest and axilla (Swift and Husband, 2014). The lymphadenopathy often shows symmetry, but is not contiguous (De Vita et al, 2016). NHL has a different pattern: the clustering of lymph nodes is common and disease can present above or below the diaphragm, or both. Patients with disease above and below the diaphragm are staged with more extensive disease, which is associated with a poor prognosis (Shankland et al, 2012).

Treatment options

The key aim of treatment for HL and NHL is remission, which the National Cancer Institute (2017) defines as an absence of signs or symptoms in a patient with a diagnosed malignancy that cannot be surgically removed. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) guideline on NHL recognises that, although there has been more understanding of disease subtypes that allows more specific treatment regimens, the paucity of research is reflected in the modest improvement in patient outcomes.

Hodgkin lymphoma patients will be offered treatment with combination chemotherapy, most commonly with a regimen that is abbreviated to ABVD, which includes doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2021a) (Table 1). These drugs are administered in 28-day cycles, with all drugs given on days 1 and 15, along with a number of supportive medications tailored to individual patient need. The combination therapy will be administered for 2–6 cycles, depending on disease staging. At each treatment interval patients are assessed for fitness for treatment using the National Cancer Institute (2019) common toxicity criteria for adverse events, alongside an evaluation of up-to-date blood tests and a patient's emotional and psychological wellbeing.

If suggested by the multidisciplinary team (MDT) at initial discussion or if an end-of-treatment scan suggests visible residual disease, the patient may be offered radiotherapy. This treatment is given with the aim of deepening their response, but is considered carefully because late effects of chemotherapy are a common occurrence in patients with HL. These side-effects are defined as problems that occur with specific body organs or systems after initial recovery from treatment has occurred and can include cardiac compromise and secondary cancers that develop as a direct result of the treatment (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2021d).

Patients with DLBCL will also be offered combination chemotherapy, this time with CHOP or CVP drug combinations (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2021b; 2021d), with the decision whether a patient received the CHOP or CVP therapy determined by patient fitness and comorbidities. The drugs administered in CVP treatment regimens are cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone and in CHOP therapy these are cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin (hydroxydaunomycin), vincristine (oncovin) and prednisolone (CHOP). Patients with B-cell lymphoma will also be given a monoclonal antibody, most commonly rituximab, alongside the combination therapy. This regimen is given on a 21-day cycle, with all drugs administered on day 1. The patient continues to take prednisolone for a further 4 days, again alongside a number of supportive medications tailored to individual patient need. Further information on the specifics of regimens and protocols for treatment are available on the Northern Cancer Alliance website (https://tinyurl.com/NCA-haem-chem-prot).

For subtypes other than DLBCL, where CHOP/CVP is not the first line treatment, alternative combination chemotherapy regimens are likely to be offered, again this may be with the addition of monoclonal antibodies.

Patients with DLBCL will often be prescribed growth colony stimulating factor (GCSF) injections, with the aim of maintaining a functioning immune system and reducing the potential complication of chemotherapy-induced sepsis. The 2012 neutropenic sepsis guideline published by NICE indicates that mortality rates of up to 20% had been associated with episodes of neutropenic sepsis. Although NICE (2012) indicates that treatment with GCSF may reduce the duration and severity of neutropenia the immune cells present in the patients' circulation post GCSF are immature and therefore less effectual in their function as part of the immune system response to infection. Prescribing schedules for GCSF will vary by clinician and centre, in both duration and timing of administration—there are no specific guidelines on the use of this therapy to manage chemotherapy-induced neutropenia.

In relapsed disease for both diagnoses the pathway is much less clear. As in much of cancer treatment in recent years the number of available options has grown and the choice becomes much more tailored to an individual patient. For relapsed HL in older patients, brentuximab and pembrolizumab have superseded the previously used combination chemotherapy regimens DECC (dexamethasone, etoposide, chlorambucil, lomustine) and ChlVPP (chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine and prednisolone). This is due to the ability of these newer therapies to selectively target the disease site and their increased tolerability (Lai et al, 2019). The advantage to this change is that biological therapies such as these are easier to administer, often as 1-day treatments rather than multidrug, multiday regimens that can cause confusion and result in over- or underdosing, for example when self-administered by elderly patients. Although targeted therapies can have profound side-effects, their frequency is greatly reduced compared with the nausea and mucositis that is prevalent in patients being treated with combination chemotherapy regimens.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma has seen similar levels of change, with widespread use of maintenance therapies in combination with monoclonal antibodies. When considering patients with relapsed NHL, the subtype of disease is extremely relevant. For example, patients with mantle-cell lymphoma, a rare aggressive subtype of NHL, can now be offered ibrutinib, which is a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Bond and Maddocks, 2020).

According to Lymphoma Action (2021b), combination chemotherapy is still the mainstay of much relapsed disease, and both HL and NHL patients can be considered for allogenic stem-cell transplant if an assessment of their physical fitness permits it.

Prognosis

Cancer Research UK estimates that the 10-year or longer survival rate for HL is 75% (CRUK, 2021e), compared with a 55% 10-year or more survival rate for NHL (CRUK, 2021f), with many patients achieving a lifelong cure.

In the event of relapse, HL is challenging to treat. If a patient is deemed to be fit enough for surgery they will be considered for allogenic stem-cell transplant. Rivas et al (2020) reported a rate of 27% progression-free survival in this group 2 years following transplant. If the haematology team assesses a patient as unsuitable for aggressive treatment such as transplant, most likely due to poor physical fitness, the patient will have periods of treatment alternating with periods of remission. These treatments can be demanding and unfortunately it is not yet possible to effectively predict the duration of remission a patient will achieve from any treatment prior to its commencement.

Approximately 70% of patients with stage II and 50% of patients with stage III-IV NHL at diagnosis will survive beyond 5 years. Given the later age of presentation, fertility and secondary malignancy issues are greatly reduced due to patients having fewer years of life remaining, albeit not completely eradicated. Close follow-up with a consultant haematologist and haematology specialist nurse, as well as good patient education about the warning signs to look out for, will help manage the patient's ongoing health and wellbeing.

For a patients with NHL who has a relapse, as in the case of those with HL, managing relapsed and refractory disease presents the haematologist and their team with real challenges. An older patient may have more physical comorbidities, as well as potential concerns around cognitive capacity to cope with complex polypharmacy drug regimens. The growing use of tools such as the European Society for Medical Oncology Clinical Benefit Scale, as well as cancer-specific frailty indices, as discussed by Ethun et al (2017), can help the clinical team, patient and family to decide which treatment would be the best option in each case, enabling them to offer a more tailored approach.

Conclusion

Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma share some striking similarities in their presenting symptoms and approaches to treatment, but they also differ in many ways. The molecular characteristics reveal two very different diseases that often have very different prognoses. With systemic anticancer therapy being the mainstay of treatment, it is crucial that the chemotherapy team caring for each patient understands the diagnosis, to enable the health professionals to deliver strong, humane, individualised care. In order to achieve this, collaborative working between all members of the multidisciplinary team is vital and must ensure consistency across the team with each member, including nurses, having firm knowledge of the disease profile affecting their patient and the treatments available.

KEY POINTS

- Hodgkin lymphoma commonly presents in patients in their twenties and thirties, while non-Hodgkin patients are most commonly aged over 55 years

- Both patient groups are treated in the first instance with a combination chemotherapy regimen, but the agents used in, and schedules of, these regimens vary significantly

- Although different in pathology, treatment and prognosis of presenting symptoms are common to both, with weight loss and pain common, as well as often palpable lymph nodes

CPD reflective questions

- In your practice, consider how holistic management of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) might vary, depending on the different stages of life at which they experience a cancer diagnosis

- Consider the information needs of patients with HL and NHL. Explore the available disease-specific-support groups and resources available for these patients and whether you educate them about these as part of your nursing care?

- Reflect on your knowledge of cancer treatments for HL and NHL and their side-effect profiles. What nursing interventions can be used to minimise their impact on the patient and family?