Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men in the UK, with thousands of new cases diagnosed each year (Cancer Research UK (CRUK), 2025). It primarily affects older men, with many cases occurring in those aged over 65 years. As the population ages, the incidence of prostate cancer is expected to rise, making it increasingly important for health professionals to be well-informed about this condition and its management.

Pathophysiology of prostate cancer

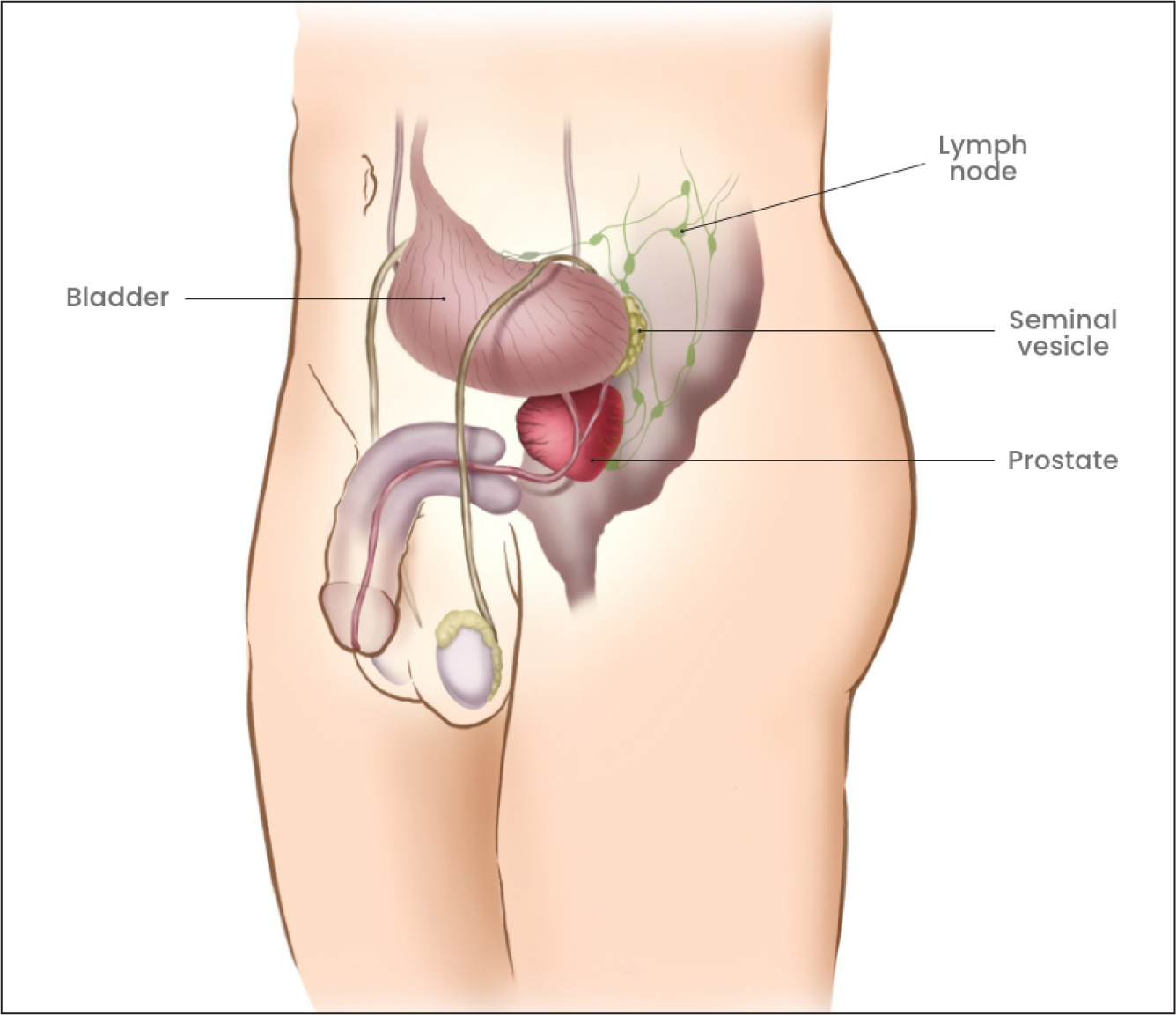

Prostate cancer originates in the prostate gland (Figure 1), a small walnut-shaped gland that produces seminal fluid, which nourishes and transports sperm. Approximately 95% of prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas, which develop from the gland cells responsible for producing this fluid (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021). Around 70% of adenocarcinomas typically arise in the peripheral zone of the prostate, where they can often be detected during digital rectal examinations (DREs). Some 20% arise in the transitional zone and 10% in the central zone. Transitional cell carcinoma of the prostate starts in the cells that line the tube carrying urine to the outside of the body (the urethra). This type of cancer usually starts in the bladder and spreads into the prostate (CRUK, 2022).

The exact cause of prostate cancer remains unknown, but several risk factors have been identified, including age, family history, ethnicity and lifestyle factors (Rawla, 2019).

Cellular and molecular mechanisms

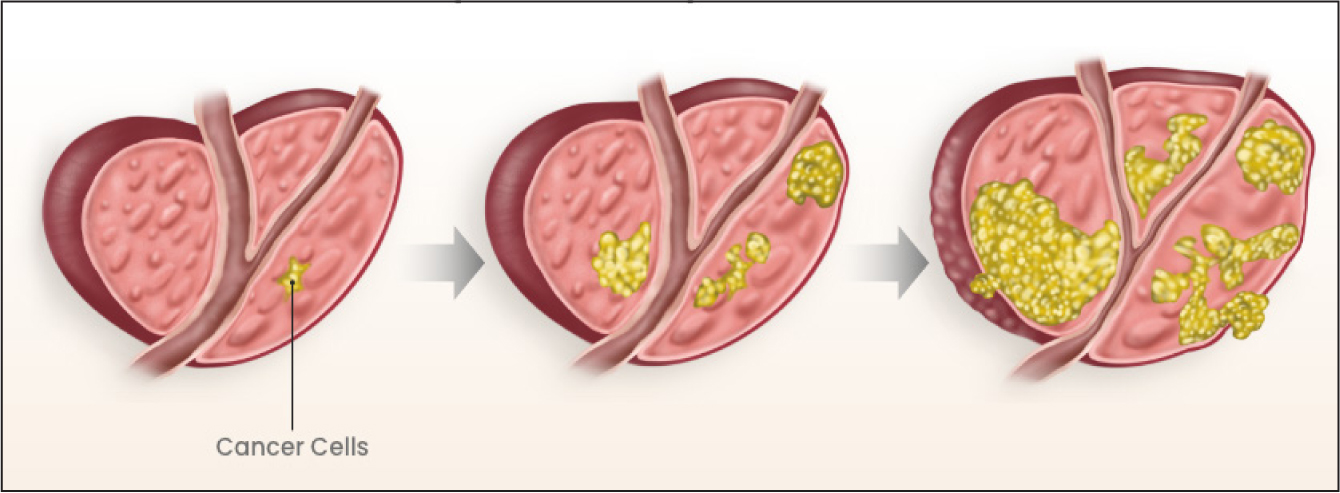

At the cellular level, prostate cancer is characterised by the uncontrolled proliferation of prostate cells (Figure 2). This abnormal growth is driven by genetic mutations that accumulate over time. Key genetic alterations include mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which are also implicated in breast and ovarian cancers. Additionally, changes in the androgen receptor (AR) gene can enhance the growth-promoting effects of androgens, the male hormones that stimulate prostate cancer cell growth. The loss of tumour suppressor genes such as PTEN and TP53 further contributes to the malignant transformation of prostate cells (Kirby et al, 2011).

Hormonal influence

Androgens, including testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), play a crucial role in the development and progression of prostate cancer. These hormones bind to androgen receptors in prostate cells, promoting cell growth and division. Although androgens are essential for normal prostate function, their presence can also drive the proliferation of cancerous cells. This hormonal influence highlights the importance of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in treating advanced prostate cancer, as reducing androgen levels can significantly inhibit tumour growth (Gudenkauf et al, 2024).

Inflammation and prostate cancer

Chronic inflammation has been implicated in the development of prostate cancer. Inflammatory processes can cause DNA damage, promote cellular proliferation, and inhibit apoptosis (programmed cell death), creating an environment conducive to cancer development. Prostatitis, a condition characterised by inflammation of the prostate, is considered a potential risk factor. Inflammatory cells release cytokines and growth factors that can stimulate the growth of prostate cancer cells and enhance their invasive properties (Sfanos and De Marzo, 2012). However, the research on this topic has had conflicting results. A large study by Beckmann et al (2019) found no consistent evidence linking prostate cancer risk to a history of chronic inflammatory diseases. They suggest that the increased risk of prostate cancer is likely to be due to detection bias. Alternatively, Rani et al (2019) stated that prostate cancer is a solid malignancy triggered by an environment of chronic inflammation, generated because of inappropriate stimulation of hormones, exposure to chemicals or radiation, or various partially known and unknown causes, such as viral infections.

Progression and metastasis

The progression of prostate cancer can vary significantly among patients. Some cancers grow very slowly and may not cause significant harm, often remaining confined to the prostate gland. These indolent cancers can be managed with active surveillance, involving regular monitoring without immediate treatment. However, other prostate cancers are more aggressive and can spread rapidly to other parts of the body, particularly the bones and lymph nodes (PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, 2025).

The process of metastasis involves several steps. Initially, cancer cells invade surrounding tissues and penetrate blood vessels and lymphatic channels. These cells then travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to distant sites, where they can establish new tumours. Wyatt and Hulbert-Williams (2015) described the stages of metastatic spread as:

Bone is the most common site of metastasis for prostate cancer, often resulting in painful and debilitating bone lesions. The molecular mechanisms underlying metastasis are complex and involve interactions between cancer cells and the microenvironment of the metastatic site (Nguyen et al, 2009).

Advanced metastatic prostate cancer cannot be cured; however, it can be controlled with various treatments which can relieve symptoms, extend life and improve the patient's quality of life. These treatments include hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2025a).

Genetic and epigenetic changes

Prostate cancer development and progression are driven by a combination of genetic and epigenetic changes. Genetic mutations can activate oncogenes, which promote cell growth, and inactivate tumour suppressor genes, which normally inhibit cancer development. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, can alter gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence. These changes can lead to the activation of genes that promote cancer growth and the silencing of genes that suppress tumour formation (Jones and Baylin, 2007).

Molecular subtypes

Recent research has identified several molecular subtypes of prostate cancer, each with distinct genetic and clinical characteristics. For example, the ETS gene fusion-positive subtype involves the fusion of the TMPRSS2 gene with an ETS family gene, such as ERG. This fusion results in the overexpression of oncogenic ETS transcription factors, driving cancer progression. Another subtype is characterised by mutations in the SPOP gene, which encodes a protein involved in regulating protein degradation. Understanding these molecular subtypes can help tailor treatment strategies to the specific characteristics of a patient's cancer (Abeshouse et al, 2015).

Tumour microenvironment

The tumour microenvironment plays a critical role in prostate cancer progression. This environment consists of various cell types, including immune cells, fibroblasts and endothelial cells, as well as extracellular matrix components. Interactions between cancer cells and the surrounding microenvironment can influence tumour growth, invasion and resistance to therapy. For instance, cancer-associated fibroblasts can secrete growth factors and extracellular matrix proteins that support tumour growth and metastasis (Mueller and Fusenig, 2004).

Emerging biomarkers

Research is ongoing to identify biomarkers that can improve the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. Biomarkers such as prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3) and the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion gene have shown promise in detecting prostate cancer and predicting disease progression. Additionally, liquid biopsy approaches, which involve the analysis of circulating tumour cells and cell-free DNA in blood samples, are being developed to provide minimally invasive methods for monitoring prostate cancer (Scher et al, 2017).

Diagnosis

Early detection of prostate cancer is crucial for successful treatment. Diagnosis typically involves a combination of methods. The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test is a blood test that measures the level of PSA, a protein produced by the prostate gland. Elevated levels can indicate the presence of prostate cancer, although other conditions can also cause high PSA levels (NICE, 2025). A DRE is a physical examination where a health professional inserts a finger into the rectum to feel the prostate gland for abnormalities. If PSA levels are elevated or a DRE is abnormal, imaging tests such as MRI and CT scans are used to determine the extent of cancer and whether it has spread to other parts of the body. A biopsy will then be performed to confirm the diagnosis. This involves taking small samples of prostate tissue to examine for cancer cells. However, this is an invasive procedure, with a high risk of infection (Royal Marsden, 2025). Other risks include bleeding, pain and difficulty urinating (CRUK, 2022).

Treatment options

The treatment of prostate cancer depends on various factors, including the stage and grade of cancer, the patient's age and overall health, and patient preferences. Common treatment options include active surveillance, surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and newer treatments such as immunotherapy and targeted therapy (NICE, 2021).

Active surveillance involves regular monitoring for low-risk, slow-growing cancers, instead of immediate treatment. This approach includes regular PSA tests, DREs, and biopsies (Klotz et al, 2015; Timilshina et al, 2023). Active surveillance for patients with prostate cancer is a standard treatment option for patients at low risk. Active surveillance serves as a critical link between identifying patients for whom early diagnosis is critical to cure and those who may be spared treatment interventions (Van Veldhuizen, 2023). Surgery, specifically radical prostatectomy, involves the removal of the entire prostate gland and some surrounding tissue. This option is often considered for healthy men with localised prostate cancer. Long-term studies, such as the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4 (SPCG-4), have demonstrated that radical prostatectomy can significantly reduce prostate cancer–specific mortality and the risk of metastasis in men with clinically localised prostate cancer (Bill-Axelson et al, 2014; Dahm and Wilt, 2025).

Hormone therapy, also known as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), reduces the levels of male hormones that can promote cancer growth. It is often used in combination with other treatments for advanced prostate cancer (Gillessen et al, 2022). Chemotherapy is used primarily for advanced prostate cancer that no longer responds to hormone therapy. It involves using drugs to kill cancer cells or stop them from growing (Petrylak et al, 2004). Immunotherapy and targeted therapy use the body's immune system or specific drugs to target cancer cells more precisely, typically for advanced or recurrent prostate cancer (Beer et al, 2014). All treatment options, including active surveillance should follow best practice as per NICE guidance (NICE, 2021).

The role of nurses

Nurses play a pivotal role in supporting patients with prostate cancer, particularly through education about diagnosis, treatment options and potential side effects. By providing clear and accurate information, nurses empower patients to make informed decisions about their care (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2018). This educational role extends to explaining the purpose and process of diagnostic investigations, treatment procedures, and follow-up plans. As key members of the multidisciplinary team, nurses also help co-ordinate care, ensuring a seamless and holistic journey through the healthcare system for men and their partners (Bennett et al, 2020).

Within treatment management, nurses are responsible for administering therapies, monitoring for adverse effects, and addressing complications as they arise. Their duties include ensuring accurate medication administration, reinforcing the importance of treatment adherence and managing common side effects such as nausea, fatigue and radiation-induced skin reactions (NMC, 2018; Bennett et al, 2020).

Prostate cancer specialist nurses enhance care delivery by applying holistic nursing models that prioritise individual needs, providing support, education, side effect management and rehabilitation. They also play a crucial role in improving access to high-quality, person-centred care (Prostate Cancer UK, 2025). Their approach considers the physical, psychological and social aspects of wellbeing.

Prostate cancer can have a significant emotional and psychological impact on patients and their families. Nurses provide essential psychosocial support by offering emotional support and counselling to help patients cope with their diagnosis and treatment. Nurses are best placed in the team to detect distress and implement effective psychosocial care either through their own nurse-led intervention or by referring to appropriate services (Jakimowicz et al 2020). Prostate Cancer UK (2022) has highlighted the significant challenges patients and their families can experience on diagnosis, and the emotions and feelings of fear, anxiety, shock and uncertainty experienced. Additionally, the charity discusses the greater risk of depression and anxiety experienced by men with prostate cancer and their partners. Encouraging participation in support groups, where patients can share experiences and receive mutual support, is beneficial (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2025b). Providing support and education to family members, helping them understand the patient's condition and how they can assist in their care, is also crucial. Carrieri et al (2018) highlighted that patients with a cancer diagnosis who received supportive care felt care was holistic and improved their quality of life. Patients reported that avoiding a simply clinical approach reduced stress levels for them and their families.

A significant challenge for patients living with prostate cancer, and their partners, is the impact on sexuality. Williams and Addis (2021) discussed the impact of cancer and how subsequent treatments can have serious implications for patients' sexuality, both physically and psychologically. They advised that patients report inadequate communication and support from professionals in relation to sexual issues, highlighting the need for adequate staff training to improve confidence and skills in this area of practice. The specialties of cancer and palliative care pride themselves on total holistic patient care; however, until this identified gap in clinical practice is addressed, true patient-centred holistic care may not be achievable (Williams and Addis, 2021).

Providing dietary advice and support to help patients maintain a healthy diet is essential, as nutritional wellbeing has been linked to improved quality of life and treatment tolerance among cancer patients (Xu et al, 2023). Encouraging physical activity, tailored to the individual's health status and capacity, can also help reduce cancer-related fatigue, enhance mood and improve overall wellbeing (Misiag et al, 2022).

Holistic care involves addressing the physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs of patients. Nurses are expected to adopt a holistic approach by developing personalised care plans that reflect the individual's values, preferences and support systems. Macmillan Cancer Support (2025c) introduced the Holistic Needs Assessment (HNA) tool, which supports health professionals in identifying and responding to the varied concerns and priorities of people living with cancer.

Clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), particularly prostate cancer specialist nurses, play a crucial role in delivering holistic, person-centred care. They provide expert knowledge, co-ordinate care pathways, and offer tailored psychological and emotional support throughout the cancer journey. According to Prostate Cancer UK (2025), CNSs significantly improve patient experience and outcomes by ensuring continuity of care and advocating for timely, appropriate interventions.

Challenges and future directions

Nurses play a crucial role in prostate cancer care, but several challenges can hinder their ability to deliver optimal support. High workloads and staff shortages may reduce time spent with patients, affecting care quality. Staying updated on evolving treatments requires continuous professional development, which can be limited by time and resource constraints. Additionally, caring for patients with advanced disease or at the end of life can be emotionally demanding, underscoring the need for mental health support for nurses (Bennett et al, 2020).

The future of prostate cancer care will be shaped by ongoing advances in personalised medicine, innovative therapies, telehealth and patient-centred approaches. Personalised medicine, including the use of polygenic risk scores and genomic profiling, enhances treatment precision and effectiveness (Cross et al, 2022). New therapies – such as androgen receptor pathway inhibitors and immunotherapies – are showing promise in improving outcomes for men with advanced or resistant prostate cancer (Wang et al, 2022). Telehealth supports remote monitoring and improves access for patients in underserved areas, offering convenience and continuity of care (Agochukwu et al, 2018; Dwyer et al, 2023). Patient-centred care, including tools such as the HNA, ensures that treatment aligns with each patient's individual needs and preferences (Macmillan Cancer Support, 2025c).

Conclusion

Prostate cancer remains a significant health challenge, particularly among older men. Nurses play a crucial role in managing this condition through patient education, treatment management, psychosocial support and holistic care. By staying informed about the latest advances in prostate cancer care and adopting evidence-based practices, nurses can significantly improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Continuous professional development, being part of a skilled, highly trained team with a sufficient number of staff, and emotional support for nurses are essential to overcoming the challenges they face in providing optimal care. As research and technology continue to evolve, the future of prostate cancer care looks promising, with new therapies and personalised approaches offering hope for better patient outcomes.