Parastomal hernia (PH) is a type of ostomy complication related to the subsiding of parastomal tissues, characterised by the protrusion of intestines through the muscle defect into the abdominal wall near the ostomy and is a very common complication (Murken et al, 2019; Pennings et al, 2021). PH is defined as a late complication (Rajapandian et al, 2020), but some studies do show that it can occur in the first month after ostomy creation (Kwiatt et al, 2013).

Although some authors have explained certain aspects, such as the aetiology of PH (Murken et al, 2019; Pu et al, 2019; Rajapandian et al, 2020; Pennings et al, 2021), there are still unanswered questions, for example the reported incidence of this complication is highly variable across the literature. In addition, there is no conformity in the definition, or diagnostic approach (clinical or radiological) used to confirm PH. Various studies are influenced by the types of ostomies observed and the length of the follow-up observation period. The information available in the literature appears to be limited regarding the prevention and treatment of PH and its impact on quality of life (QoL) (Pennings et al, 2021).

Literature review

For this overview, the authors wanted to analyse the incidence of PH, aetiology, prevention and conservative treatment. A further aim was to evaluate the impact of PH on QoL. In both cases, the aim was to consider patients with ileostomy, colostomy or urostomy. A research strategy was created using both controlled and free terms. Major databases such as Medline-PubMed and Embase were consulted in June 2022 (18-20 June) without filters. The following keywords were used: ostomy, stoma, colostomy, ileostomy, urostomy, complication, parastomal hernia, aetiology, prevention, treatment, nurse, nursing, quality of life.

Incidence and aetiology

The incidence of PH is reported as ranging from 2% to 58% (Carne et al, 2003; De Raet et al, 2008; Carlsson et al, 2016; Donahue and Bochner, 2016; Antoniou et al, 2018; Harries et al, 2021; Maglio et al, 2021), but in some studies, this rate is as high as 65% or even 86% (Aquina et al, 2014; Donahue and Bochner, 2016; de Smet et al, 2020; Odensten et al, 2020). However, there is consensus in the literature that the incidence of PH increases with a longer period of observation and follow-up (Carne et al, 2003; Näsvall et al, 2014; Donahue and Bochner, 2016; Kroese et al, 2018). The incidence can increase from 30% in the first year to 40% in the second year, and within 5 years after the intervention, the incidence can grow to more than 50% (Carne et al, 2003; Antoniou et al, 2018). In most cases, this complication develops in children or older people over 70 due to reduced muscle tone (North and Osborne, 2017; Niu et al, 2022). However, there are many predisposing factors for PH. Some relate to the patient, others to the type of surgery or ostomy created (Donahue and Bochner, 2016; North and Osborne, 2017; Tsujinaka et al, 2020; Niu et al, 2022) (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. Predisposing factors for the development of parastomal hernia

| Main patient-related factors * |

|

| Main risk factors related to the type of intervention † |

|

Sources:

*Seo et al, 2011; Aquina et al, 2014; Donahue et al, 2014; Carlsson et al, 2016; Donahue and Bochner, 2016; North et al, 2017; Osborne et al, 2018; Denti et al, 2020; Tsujinaka et al, 2020; Xie et al, 2021; Niu et al 2022

†Seo et al, 2011; Hotouras et al, 2013; Aquina et al, 2014; Carlsson et al, 2016; Donahue and Bochner, 2016; North et al, 2017; Antoniou et al, 2018; Xie et al, 2021; Niu et al 2022

Table 2. Incidence by type of ostomy

| Type of ostomy | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Loop colostomy | 0–30.8% |

| End colostomy | 4–48.1% |

| Loop ileostomy | 0–6.2% |

| End ileostomy | 1.8–28.3% |

| Urostomy | 5–35.4% |

Assessment of parastomal hernia

There is no gold standard for determining the presence of PH (Näsvall et al, 2014; de Smet et al, 2020). Several diagnostic modes exist to detect PH (Śmietański et al, 2014). This is one of the factors that most influence the variability of the incidence rate in the literature (Näsvall et al, 2014; Donahue and Bochner, 2016). In clinical practice, the objective examination is the first method to assess the presence or absence of PH and this is performed by the stoma care nurse (SCN) and/or surgeon (de Smet et al, 2020; Lambrecht, 2021). It consists of examining the patient lying down and standing up to determine the PH's size and severity and the conformation of the ostomy. PH can be classified according to size and presence of concomitant incisional hernia (CIH), resulting in four levels (Śmietański et al, 2014) (Table 3).

Table 3. Parastomal hernia classification

| Type | Dimension | Presence of CIH |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | Small (<5 cm) | No |

| Type II | Yes | |

| Type III | Large (>5 cm) | No |

| Type IV | Yes |

CIH = concomitant incisional hernia

Source: Śmietański et al, 2014Obesity and the presence of severe pain on palpation may invalidate the objective examination (Donahue and Bochner, 2016; Styliński et al, 2018). If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, an imaging modality such as an ultrasound scan or computed tomography (CT) is used (Antoniou et al, 2018; Styliński et al, 2018de Smet et al, 2020). There are not many studies using ultrasound for PH diagnostics (Näsvall et al, 2014; Xie et al, 2021). Ultrasound scan appears to be a safe, less expensive method in contrast to CT, and it allows the patient to be assessed in both the upright and supine positions (Näsvall et al, 2014). In addition, the technique of intrastomal 3D ultrasound scan has recently begun to be used, given its ability to produce accurate imaging (de Smet et al, 2020). The ultrasound scan may cause pain, and the 3D ultrasound scan technique cannot be used in the presence of ostomy stenosis (Näsvall et al, 2014).

CT is an accurate diagnostic modality (sensitivity of 83%) for PH diagnosis and increases PH detection rates compared with clinical examination (de Smet et al, 2020). This imaging method is widely used because ostomy patients often have regular CT follow-ups for oncological reasons. CT has the disadvantage that it uses ionising radiation and is more expensive than other imaging methods (de Smet et al, 2020).

Prevention

Interventions aimed at PH prevention are recommended in the literature, and these include surgical interventions and those by an SCN (North and Osborne, 2017; Osborne et al, 2018; Tsujinaka et al, 2020).

Extra-peritoneal ostomy creation and the use of intraoperative mesh represent the main surgical interventions, especially in the case of permanent ostomy creation (Tsujinaka et al, 2020; Niu et al, 2022). Although good evidence exists to support the prophylactic use of mesh, this procedure has not been adopted on a large scale because of concerns about possible complications such as infection, erosion, and other mesh-related complications (Park et al, 2022).

The literature highlights that high-quality support from the SCN before, during and after surgery is essential for positive outcomes in ostomy patients (Villa et al, 2018). SCN interventions are based on the implementation of a programme aimed at an accurate assessment of the patient and risk factors, implementation of pre-operative stoma siting, education related to body weight management, diet and how to perform physical exercises correctly. (North and Osborne, 2017; Osborne et al, 2018; Thompson, 2008; Tsujinaka et al, 2020).

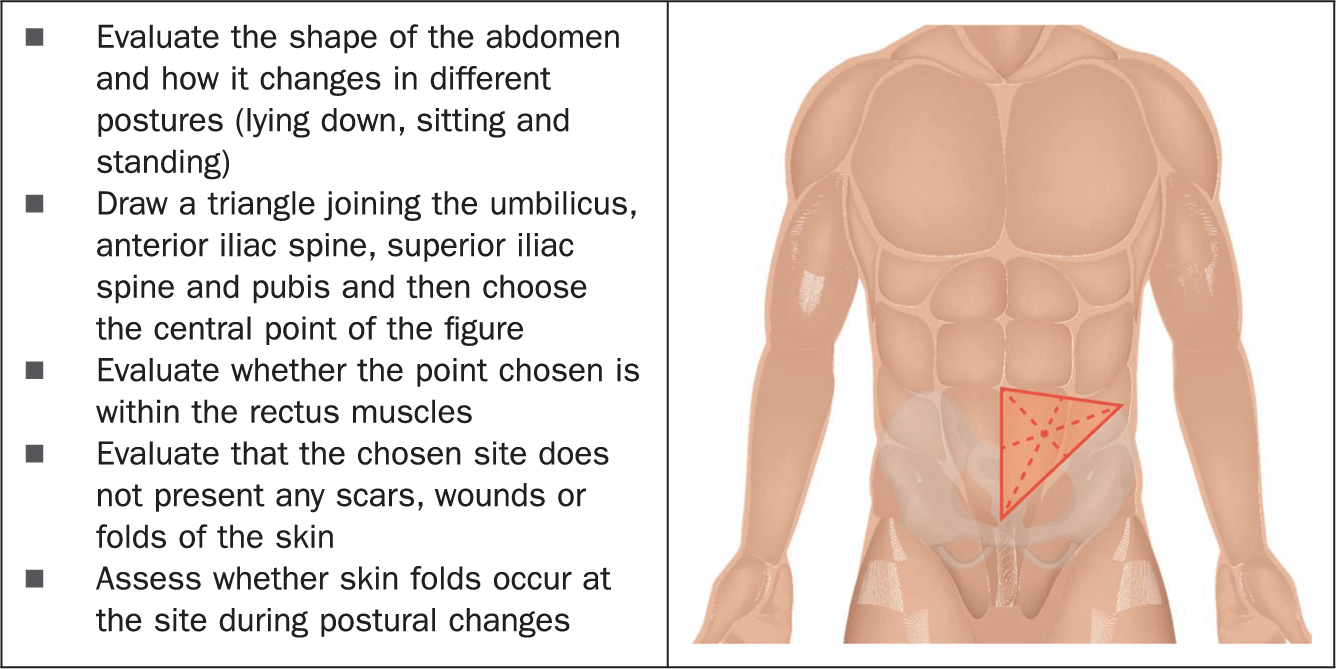

The process of ostomy siting, which should be carried out with all patients undergoing elective ostomy creation, is helpful in identifying the most appropriate site for ostomy formation. This improves postoperative QoL by facilitating patients' independence, reducing the rate of postoperative complications and reducing management costs (Person et al, 2012; Roveron et al, 2016; Xie et al, 2021). The ostomy siting procedure is outlined in Figure 1.

Osborne et al (2018) highlighted the importance of initial assessment and proposed the development of a tool to measure and identify PH risk factors, allowing the SCN to personalise care by performing targeted preventive actions.

Due to increasingly rapid hospital discharges, many patients do not acquire all the knowledge and techniques needed to properly manage their ostomy (Villa et al, 2018). For this reason, one of the main objectives, even before surgery, is to develop an individualised and agreed care plan, aiming for the patient's best possible QoL and optimal reintegration into society (Villa et al, 2018).

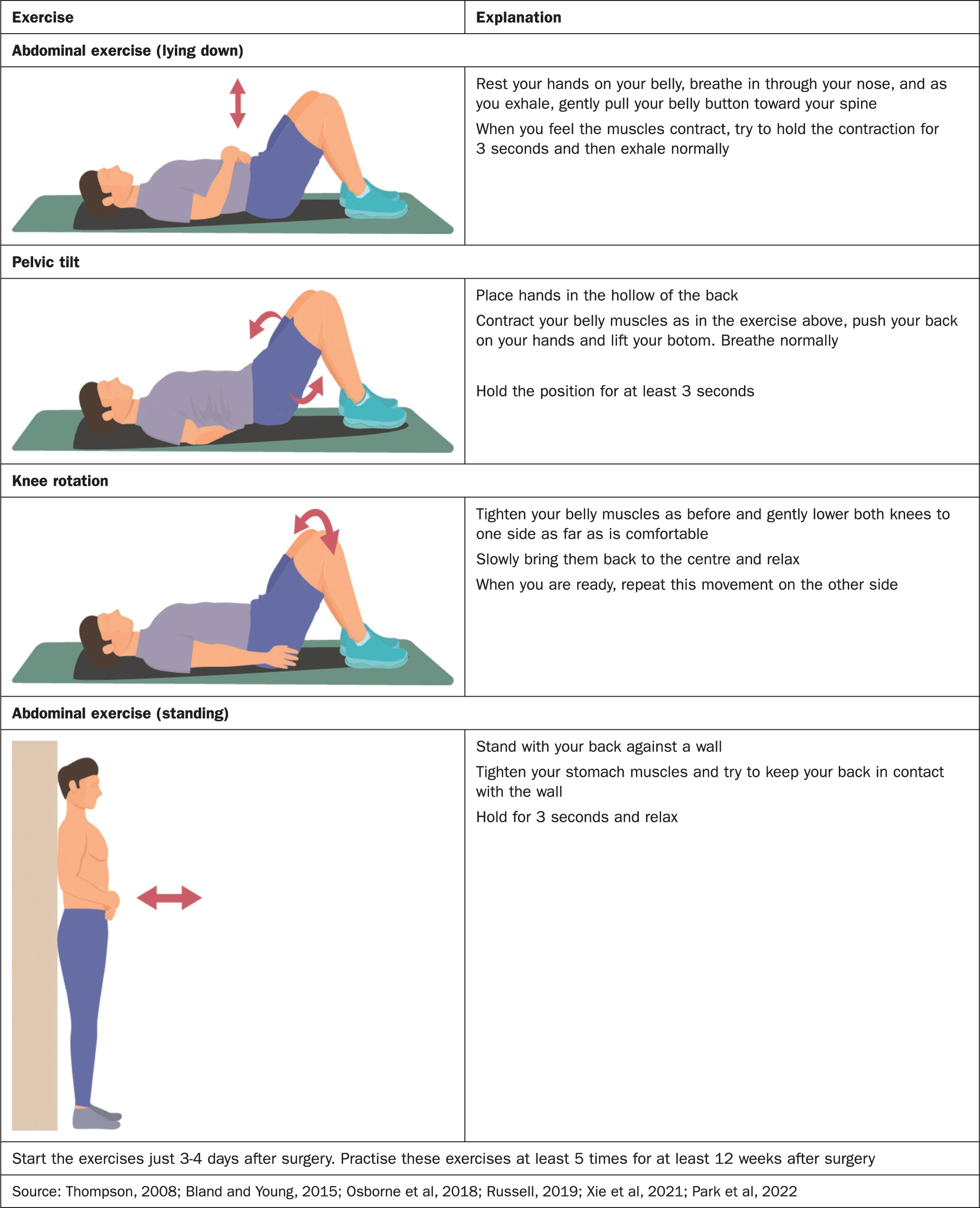

Educating patients on maintaining or achieving an adequate body weight, with a BMI between 20 and 25, is crucial for preventing the onset of PH (Bland and Young, 2015). Obese patients with a large waistline have increased abdominal pressure, which weakens the abdominal wall. (Bland and Young, 2015; Xie et al, 2021). Individuals with a PH need to be informed of the importance of a diet and fluids to ensure soft stool and to prevent constipation. Exercise allows the person to maintain an adequate BMI as well as providing numerous health benefits (Bland and Young, 2015; Russell, 2019.). For these reasons the ostomy patient may be encouraged to exercise (Bland and Young, 2015; Russell, 2019). In particular, there are physical exercises designed to strengthen the abdominal muscles that ostomates can perform (Thompson, 2008; Bland and Young, 2015; Osborne et al, 2018; Russell, 2019; Xie et al, 2021; Park et al, 2022) (Figure 2).

As with other complications of a complex ostomy, specialist evaluation and follow-up over the longer term is required with the aim of early detection of possible PH and early management (so-called ‘early treatment’) (Villa et al, 2021). As a result, the patient must therefore be educated in the self-assessment of the ostomy and it is essential to develop a personalised follow-up care plan for the patient (Maculotti et al; 2020; Villa et al, 2021).

PH management

The management of PH management can be conservative or surgical (Tsujinaka et al, 2020). It is estimated that 5-30% of patients would eventually require corrective surgery (Donahue and Bochner, 2016; Colvin and Rosenblatt, 2018; Odensten et al, 2020; Harries et al, 2021). The decision to electively treat a PH is primarily based on pain, psychological distress associated with the patient's physical appearance and/or inability to hide a hernia under clothing, and difficulty in managing the collecting device. Obstruction, incarceration or strangulation results in urgent intervention (Donahue and Bochner, 2016; Colvin and Rosenblatt, 2018; Odensten et al, 2020). The type of surgery is chosen based on the size and location of the hernia, the patient's general health condition, age, and surgical and anaesthetic risk (Colvin and Rosenblatt, 2018). The recurrence rate in the surgical treatment of PH in the latest studies is between 3% and 22% (Odensten et al, 2020).

Many PHs can be managed non-surgically. In fact, watchful waiting for patients with PH is a common practice, although relevant evidence is scarce; but the high recurrence rates after PH is repaired and the lack of symptoms in a considerable proportion of patients with PH make the conservative approach an attractive option (Antoniou et al, 2018; Colvin and Rosenblatt, 2018; Kroese et al, 2018). Conservative treatments needed include using elastic restraining devices (support belts/garment), soft and flexible skin barrier or pouch, barrier films and discontinuation of ostomy irrigation. In addition, patient education on proper exercise, nutrition and hydration remain important, promoting soft stool formation and maintaining an optimal BMI (Donahue and Bochner, 2016; Colvin and Rosenblatt, 2018; Tsujinaka et al, 2020; Xie et al, 2021).

Quality of life

The creation of an ostomy could reduce the patient's QoL (Maculotti et al, 2020). Ostomy patients might suffer from changes in their body image, expressing feelings of anxiety and depression. Some patients reported difficulties with work and social functions, sexuality, ostomy management and good self-care (Wiskemann et al, 2016; Villa et al, 2018). All these changes can have a negative impact on the patient's QoL and health (Villa et al, 2018). Furthermore, the onset of a complication can further lower the quality of life of the ostomy patient (Vonk-Klaassen et al, 2016).

If the PH becomes very conspicuous and unwieldy, this can negatively affect the person's QoL due to discomfort, pain, frequent problems in managing the ostomy device or related skin irritations (Aquina et al, 2014; Temple et al, 2016; Harries et al, 2021; Park et al, 2022). In addition, PH is accompanied by various psychosocial problems (eg, feeling depressed and tired, dissatisfaction with appearance, change of clothing and concern about ostomy noises) that negatively affect QoL (Vonk-Klaassen et al, 2016; Wiskemann et al, 2016). These problems can be so severe that up to a third of patients require surgery to correct PH (Donahue and Bochner, 2016; Harries et al, 2021).

Reducing the impact of ostomy on QoL requires a well-created ostomy, proper patient education, careful ostomy care and regular follow-ups (Ambe et al, 2018).

Conclusion

Currently, there is no standardised definition of PH although it is very common. PH is usually a late complication, but it can also occur early. Elements related to the patient and the type of surgery performed, such as BMI greater than 25, age (children or older men over 70), chronic cough, chronic constipation, emergency surgery, lack of ostomy siting by an SCN, ostomy creation outside the rectus abdominis, are the predisposing factors for the occurrence of PH. There is no gold standard for determining the presence of PH. The main evaluation techniques include objective examination, ultrasound scan and computed tomography. Prevention of PH is based on assessment of the patient's risk factors, implementation of the pre-operative plan, education and proper exercise performance. Conservative treatment, managed by an SCN, may include soft and flexible pouch systems, protective films, and discontinuation of ostomy irrigation. PH affects the patient's QoL by making ostomy management more complex. The SCN, after assessing risk factors, can tailor treatment by implementing preventive actions. In addition, programmed follow-up with an SCN to monitor the status, management, and condition of the PH is important, promoting the efficiency of ostomy self-care to combat common challenges associated with ostomy creation.

KEY POINTS

- Parastomal hernia (PH) is related to the surgical incision near the ostomy, but there is no agreed PH definition in the literature.

- The PH's incidence range from 2% to 86%

- The risk factors of PH complications are related to the type of surgery and patient-related factors including the age of patients (higher incidence in children and people older than 70 years). There is no gold standard for determining the presence of PH

- The approaches to prevent PH include nursing or surgical strategies

- PH has a huge impact on QoL

CPD reflective questions

- Is a consensus definition of parastomal hernia (PH) important? Why?

- What is the most appropriate information that needs to be provided to the patient regarding the risk of PH and to help manage a PH when it occurs?

- How can PH be prevented from impacting on a patient's quality of life?