Cancer-related pain continues to be the most reported symptom across all cancer types (Bubis et al, 2018). It is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon that not only affects people physically but also has an impact on their spiritual, social, and psychological wellbeing (Lewandowska et al, 2020; Breitbart et al, 2021). The impact of cancer-related pain is significant, it has a negative effect on the individual experiencing it and also on family members/caregivers, health professionals and wider health service provision (LeBaron et al, 2014; Erol et al, 2018; Latter et al, 2016; Mills et al, 2019).

The incidence of cancer-related pain continues to be high with 66% of those with advanced disease and 39% of those who have completed curative treatment reporting pain (van den Beuken-van Everdingen et al, 2016). Despite its high prevalence and wide impact, it remains poorly managed in practice with one-third of individuals reporting uncontrolled cancer-related pain (Greco et al, 2014). Due to the complex nature of cancer-related pain, it is essential that health professionals are adequately equipped to support individuals living with this throughout their lifespan. This scoping review aims to map the literature and explore the knowledge gaps of health professionals when confronted by the complexity of cancer-related pain.

Background

The debate regarding health professionals' knowledge of pain is well documented throughout the literature, with early work dating back to the 1980s (McCaffery and Ferrell, 1997). Throughout the decades the narrative has been the same across the literature – that knowledge of pain is poor (Ung et al, 2016; Bouya et al, 2019; Galligan and Wilson, 2020). However, the focus of these studies was more on nursing knowledge of non-cancer pain (McCaffery and Ferrell, 1997; Ung et al, 2016; Galligan and Wilson, 2020).

Although the literature points to knowledge of pain being poor, it also shows us that there are themes regarding poor knowledge and misconceptions of specific aspects of pain assessment and management that have been present since the early work in the 1980s (McCaffery and Ferrell, 1997). This is evident in areas such as the use of opioids, risks of addiction, adverse effects, and negative attitudes towards individuals' self-reports of pain (McCaffery and Ferrell, 1997; Matthews and Malcom, 2007; Samarkandi, 2018; Galligan and Wilson, 2020). The focus of the literature is on understanding current knowledge levels, and publications provide little insight into the reasons why knowledge is poor. However, there is a growing body of literature that indicates that a lack of pain education at undergraduate education stage is a driving factor. An example of this can be seen in a study of the nursing undergraduate curriculum: in a survey of 71 UK universities there was no mention of pain education anywhere in the curriculum (Mackintosh-Franklin, 2017).

Although the above studies explored non-cancer pain, the narrative of poor knowledge continues in those studies that focused on health professionals working in cancer-related pain (Kasasbeh et al, 2017; Bouya et al, 2019). However, there are limitations to the studies that focused on cancer-related pain knowledge. This includes a focus on nurses and lack of representation of the wider multidisciplinary team, and limitations in the way the findings are being reported (Kasasbeh et al, 2017; Bouya et al, 2019). Across reviews completed by Kasasbeh et al (2017) and Bouya et al (2019) the focus was on summarising knowledge as a numerical score and not exploring if there were common areas of poor knowledge. This makes it difficult to identify areas of practice that could benefit from an intervention to improve knowledge.

Given these limitations there is an argument for exploring the current evidence base and identifying whether there are common themes regarding health professionals' knowledge of cancer-related pain. A scoping review framework was identified as a method of mapping the existing evidence to identify if these themes are present in the evidence base.

The scoping review remains a relatively new method when compared with systematic reviews. However, the methodology lends itself to this topic because of the need to map the current state of evidence regarding health professionals' knowledge of cancer-related pain (Munn et al, 2018).

Method

This review is based on the Arksey and O'Malley (2005) scoping review framework (Table 1), which is a widely used framework for healthcare scoping reviews (Pham et al, 2014). Additional recommendations made by Levac et al (2010) were incorporated to provide further detail for each stage of the review and enhance methodological rigour.

Table 1. Stages of scoping review

| 1.Identifying the research question | Development of a question that allows for a broad exploration of the literature in order to provide a structured summary of the question posed |

| 2. Identifying relevant studies | A comprehensive and systematic search of the literature in order to identify relevant sources to include in the review |

| 3. Study selection | A transparent and replicable approach to screening and selection of identified studies |

| 4. Charting the data | The collating data from the studies into a tool that facilitates analysis of the results |

| 5. Collating, summarising and reporting the results | Final analysis of the data and translation this into meaningful summary and recommendations for future practice/research |

| 6. Consultation | Engagement with stakeholders to identify additional information that could be incorporated into the final findings/recommendations of the review |

A systematic search of the literature was performed with support from an experienced academic librarian. Databases CINAHL, Medline and PsycINFO were searched using the terms ‘cancer pain’, ‘healthcare professional’, ‘knowledge’, ‘attitudes’ and ‘barriers’ for articles published between 2010 and 2020. A further search of the grey literature was also performed using the Open Grey search engine. Reference lists of selected papers were hand searched to ensure that relevant studies were not overlooked. The protocol for the scoping review was registered with Open Science Forum (osf.io/w9bsc).

The titles and abstracts of the studies identified were screened using the PIO framework (Table 2) alongside inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 3). Twenty screened abstracts were randomly selected and were reviewed by two additional researchers to ensure the inclusion criteria were valid, sensitive and to reduce selection bias. Disagreements between researchers were discussed and conflict resolved with agreement of all three researchers. Once agreement had been reached, a full-text review of the research papers was conducted by one researcher.

Table 2. PIO screening criteria

| P – Population/Problem | Health professionals |

| Nurse | |

| Doctor | |

| Physician | |

| Allied health professional | |

| Cancer pain | |

| I – Issue | Knowledge |

| Attitudes | |

| Barriers | |

| Cancer pain | |

| Cancer-related pain | |

| O – Outcome | Knowledge |

| Attitudes | |

| Barriers | |

| Attitudes of health professionals |

Table 3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

Data from research papers meeting the inclusion criteria were then extracted and fed into a results table. Key information on study location, design, methods, results and recommendations were used to capture pertinent information. A descriptive narrative approach was taken to report the findings of the research papers when establishing the methods used and knowledge deficits to cancer-related pain.

A consultation stage in the scoping review model was also completed; preliminary results of the review were presented at a pain and palliative care multidisciplinary meeting in a specialist cancer hospital.

Results

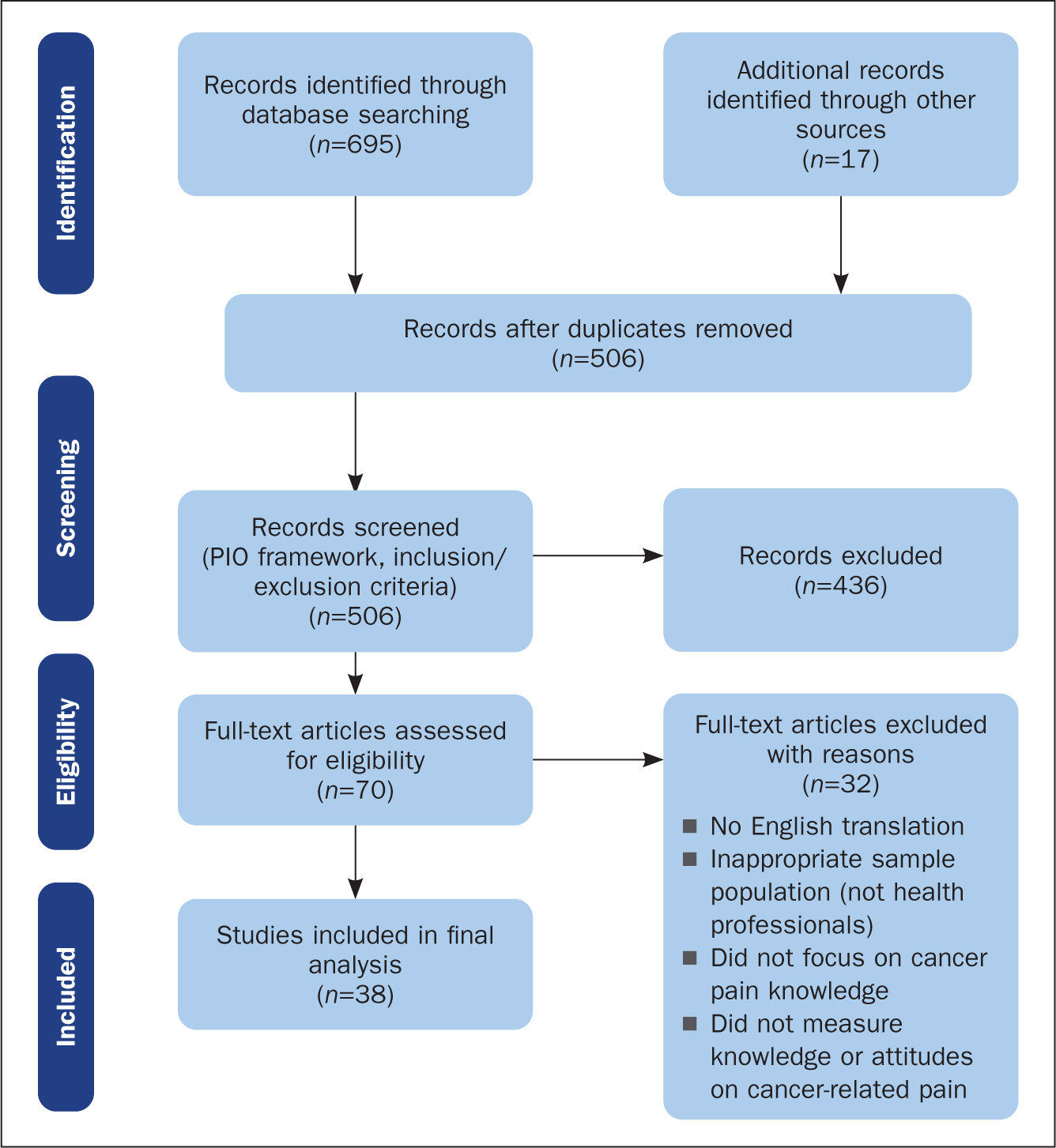

A total of 712 research papers were identified through the search strategy; following screening and full text review this resulted in 38 research papers being carried forward into data analysis. Full breakdown of the search can be seen in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1). Of the 38 research papers, 34 used a quantitative survey design, two used qualitative focus groups and interview designs and two used mixed methods. Table 4 outlines the professional backgrounds of those taking part in the studies: this was largely focused on nursing with limited involvement of allied health professionals. Interestingly, none of the studies were conducted in a UK setting.

Table 4. Demographics of included studies

| Population | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Nurses | 25 |

| Doctors | 19 |

| Pharmacists | 1 |

| Radiation therapists | 1 |

| Psychotherapists | 1 |

Studies that adopted a survey design predominantly used a locally designed questionnaire (n=19) with others opting to use Knowledge and Attitudes Survey Regarding Pain (KASRP) (Ferrell and McCaffery, 2014) (n=12), Nurses' Knowledge of Cancer Pain Management – WHO (Ramos, 1994) (n=2), Barriers Questionnaire (Gunnarsdottir et al, 2002) (n=2) and Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group (ECOG) Knowledge Survey (Von Roenn et al, 1993) (n=1). The scores generated from the papers were from general enquiries regarding pain knowledge and did not measure the impact of an educational intervention.

Twenty-four studies used a mean score to quantify the level of knowledge of participants: this represented the percentage of correct responses for the tool used. The mean knowledge score ranged between 36% and 95% across the studies. Knowledge gaps were identified across all aspects of cancer-related pain assessment and management. However, the most common gaps centred around fear of addiction, tolerance or dependence to opioids, pharmacology of analgesics, principles of cancer-related pain management, pain assessment/believing patients' reports of pain, concerns of causing adverse effects and the use of non-pharmacological and interventional techniques. The full table showing knowledge gaps identified is appended to the online version of this article.

Four studies used qualitative methods, two of which used mixed methods and combined knowledge surveys with focus groups and interviews. To establish themes across the qualitative findings the principals of thematic analysis were used. The findings from each of the studies were coded and then grouped under the following headings: knowledge gaps, ‘opioiphobia’, organisation culture, patient factors, and access to opioids (Table 5).

Table 5. Qualitative findings

| Author and date, location | Population Sample size Method | Key themes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onsongo (2020) Kenya | Nurses25Interviews/observations |

|

Support practice with pain management guidelinesChange in workforce culture is needed to change practice |

| Charalambous et al (2019) Cyprus | Doctors38Focus groups |

|

Standardised education programme for all health professionals |

| Nega and Kassa (2014) Ethiopia | Nurses22Focus groups |

|

Inclusion for pain education at undergraduate levelIn-house training around assessment and use of WHO pain ladder (World Health Organization, 2019) |

| De Silva and Rolls (2011) Sri Lanka | Nurses10Interviews and observations | Nurse-related factors:

|

Inclusion of pain education at undergraduate levelOrganisational support to improve working conditionsFocus education on assessment and management |

The findings from the qualitative studies are important to highlight and added further insight into the knowledge gap themes identified in the quantitative surveys. The term ‘opiophobia’ was used to describe these knowledge gaps as fears regarding the use of opioids such as addiction and developing adverse effects, ie respiratory depression or hastening death. Onsongo's (2020) study found that nurses feared administering morphine because they worried that this would result in addiction. Interestingly, these same nurses also reported that they had never come across an incidence of opioid addiction secondary to opioids for cancer-related pain. Onsongo (2020) also reported fears around respiratory depression when administering morphine and concerns that this would hasten death at end of life. Both of these concerns have also been expressed by Charalambous et al (2019) in their exploration of physicians' perceptions of opioid use.

These reported fears translated into poor management of individuals' pain as some professionals actively sought out alternatives to administering opioids. Nega and Kassa (2014) found that focus group participants reported that they would administer placebos to establish whether pain was real before administering an opioid. Onsongo (2020) also reported that participants would administer paracetamol in preference to opioids as they knew this did not carry a risk of addiction. These themes from the qualitative results provide valuable insight into the drivers behind the identified knowledge gaps and raise ethical issues around practice.

The consultation phase of this scoping review was completed through presentation of the preliminary results of the review at a pain and palliative care multidisciplinary team meeting within a specialist cancer hospital in the UK. These results generated a wider discussion regarding the need for access for specialist support for health professionals working in non-specialist settings but still caring for those with cancer-related pain. There were discussions regarding the transferability of the findings to a UK population, or other country, given the locations of the studies performed. However, it was agreed that there were learning points that could be applied to many settings.

Discussion

The scoping framework has provided a structured approach to mapping the scope of current literature regarding health professionals' knowledge of cancer-related pain. This sizeable volume of identified research articles gave an overview of the current knowledge base and its limitations.

Very few studies were performed in European regions. This is important to highlight given that the incidence of cancer diagnosis is highest across the western world, with Europe reporting 25% of the global cases of cancer diagnoses (Ferlay et al, 2019). Regardless of the diversity of study locations, this scoping review provided an insight into the knowledge levels of health professionals. It should also be noted that the perception and management of pain will also be impacted by culture, and this may have affected the findings of this scoping review, given the diversity of the study locations (Miller and Abu-Alhaija, 2019). In view of the multicultural populations identified in this review there will be shared learning that can be applicable to practice in the UK. However, it does highlight that there is a need for research exploring the needs of health professionals in the UK and Europe.

The findings demonstrated that existing research is centred around nurses, and to a lesser extent doctors, with limited exploration of other health professionals. With only three studies including allied health professionals, this suggests an urgent need to explore not only their knowledge base but also their perceived role in the management of cancer-related pain. It is not the sole responsibility of one professional group and an interdisciplinary approach is necessary to ensure effective management (Bennett et al, 2019). Excluding these professional groups from wider research risks diminishing the role they play in the interdisciplinary team and underplaying the need for them to support individuals with cancer-related pain.

An example of this can be seen in a survey of radiation therapists, where participants did not feel that wider knowledge regarding use and risks of opioids was relevant to their practice (Di Prospero et al, 2012). However, in the same study the authors reported that radiation therapists felt that assessment and management of pain was highly relevant to their practice, as they will encounter patients daily during a course of radiotherapy treatment (Di Prospero et al, 2012). This would suggest that they are in an ideal position to take an active role in supporting patients with cancer-related pain. This will require a knowledge of opioid analgesics, so that they can not only identify early signs of adverse effect but also initiate treatment or refer to appropriate teams. The Faculty of Pain Medicine (2019) supports this idea and recommends that all health professionals should have the ability to assess and provide initial management for those with cancer-related pain before referral on to a specialist pain or palliative care service.

Further research is needed to understand how each professional group views their role in supporting individuals with cancer-related pain. These insights are essential if we are to understand the needs of the wider workforce, only then can we truly have an interdisciplinary team approach that is embedded in all stages of diagnosis, treatment and beyond.

Knowledge gaps

Across the studies reviewed, clear gaps in the knowledge base were seen regarding all aspects of pain assessment and management (for full details see article and appendix online, 10.12968/bjon.2024.33.5.S4). On further analysis, dominant themes started to emerge relating to use and fears of analgesics (addiction/dependence, adverse effects, pharmacology knowledge), pain assessment practices (disbelieving patient reports of pain) and the role of non-pharmacological and neuraxial techniques. Underlying drivers of these knowledge gaps were further seen in the qualitative findings. These gaps in the knowledge base are not isolated to the cancer-related pain population and have been echoed in similar studies exploring knowledge of non-cancer pain (Matthews and Malcom, 2007; Galligan and Wilson, 2020).

The insights identified in the qualitative studies provided a much richer picture of knowledge gaps and reported practices in comparison with survey-based designs. Greater use of mixed method and qualitative methodology may provide a deeper insight into beliefs that perpetuate knowledge gaps and help to identify potential targets for educational interventions. Participants in all of the qualitative studies reported that their knowledge of cancer-related pain was poor and that they required further support. This insight into their practice is the first positive step towards making changes to the way in which cancer-related pain is viewed (Ferlay et al, 2019; Charalambous et al, 2019; Onsongo, 2020).

Conclusion

This scoping review has mapped the current literature in relation to health professionals' knowledge surrounding cancer-related pain and its management. The findings highlight that health professionals' knowledge is influenced by multiple factors. It is a complex issue that requires support from the wider multidisciplinary team to address it. If cancer-related pain is to be effectively managed, a clear outline of what is expected from health professionals needs to be established. Only then can we truly begin to address the complexity of cancer-related pain and support those living with it.

KEY POINTS

- Cancer-related pain is complex and can occur at any stage following a cancer diagnosis. Its impact extends beyond the individual experiencing it, to those around them and wider healthcare services

- To support those affected by cancer-related pain health professionals need to have adequate knowledge, skills and confidence in its assessment and management

- Common knowledge gaps arte evident across the literature with regard to cancer-related pain in relation to pain assessment and management

- The literature suggests that health professionals' knowledge of cancer-related pain is poor, and more support is needed to develop their knowledge, skills and confidence regarding cancer-related pain. This is essential to deliver adequate support to those living with cancer-related pain

CPD reflective questions

- Think about individuals in your care living with cancer-related pain. What are the key knowledge and skills required to support them?

- Are there any aspects of caring for those with cancer-related pain about which you feel you have insufficient knowledge and skills. If so, how might you address this?

- Consider the patients you have cared for with cancer-related pain. How could their management have been improved?

- Think about the wider multidisciplinary team. How does your role differ from theirs, and how can a collaborative approach be used to support those impacted by cancer-related pain?