The incidence of uterine cancer is increasing (Lortet-Tieulent et al, 2018). The most common cancer is hormone-responsive (type 1) endometrioid adenocarcinoma. In the UK, the follow-up practice after treatment for uterine cancer is to review the patients in clinic regularly for 5 years. However, the 5-year survival for stage 1A, grade 1 endometrial cancers is 95% (SEER, 2020) and most women will not have a recurrence. Furthermore, a recurrence is not usually diagnosed at routine follow-up but brought to medical attention because of symptoms (Salani et al, 2011; Jeppesen et al, 2017). Anecdotally, cancer patients in general experience anxiety when attending follow-up visits.

There is a drive from various bodies, including the British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS), to consider other means of follow-up for cancers with a good prognosis, which are safe and acceptable to patients. Any reduction in follow-up may help reduce anxiety for a significant number of women. BGCS guidelines state ‘the data is not robust enough to allow us to calculate the utility of follow-up with precision but women with low risk endometrial cancer should be reassured that failure to attend at a follow-up clinic is extremely unlikely to be detrimental to their survival prospects’ (Sundar et al, 2017). This statement supports the suggestion that a clinical follow-up is perhaps not necessary to diagnose recurrence in low-grade, early-stage cancers that are at a low risk of this. Furthermore, many studies have been done to show an intensive surveillance protocol seems to have no significant impact on the outcome of patients with stage 1 endometrial cancer (Gadducci et al, 2000).

Therefore, there is a need to stratify cancer patients by risk based on their likelihood of recurrence and prognosis. Patients with low-risk cancers should have alternative means of follow-up to those for patients with cancers that have a poor prognosis.

A district general hospital changed its follow-up protocol in November 2013. The original protocol consisted of four clinic visits in the first year, three clinic visits in the second year, two clinic visits in the third year and annually in the fourth and fifth years. Instead of these regular appointments, patients with low-risk endometrial adenocarcinoma were put on a patient-led follow-up programme. This new follow-up protocol was audited by a medical student in 2019.

Aims

This study aimed to identify:

Methods

All women who underwent surgery as their definitive treatment for uterine cancer were reviewed postoperatively in the cancer multidisciplinary team for confirmation of the final stage and grade of cancer. Those with a stage 1A, grade 1 endometrioid adenocarcinoma were included in this study and were reviewed first by the operating surgeon 2–4 weeks after surgery. At this appointment, the patients were offered either routine clinical follow-up for 5 years or a patient-led telephone follow-up, where they could call the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) team at any time if they had any concerns.

All of the patients took up the offer of the telephone follow-up and saw a gynaecology oncology CNS within the following 4-6 weeks. During this 1-hour consultation, the nurse carried out a holistic needs assessment that looked at the patient's physical, emotional, family and spiritual concerns, and an individual care plan was made. Healthy lifestyle, diet and exercise in relation to general wellbeing and in reducing the risk of heart disease, stroke, diabetes, osteoporosis and getting another primary cancer was also discussed. Some patients who lived in a certain area were eligible to be referred to a council-run 18-month long exercise programme. Nurses would also identify whether patients required a referral to other support services.

There was a detailed discussion regarding their diagnosis, the treatment received and the favourable prognosis of their cancer. They were again offered a patient-led follow-up or traditional clinical check-ups. All of the women were then educated regarding symptoms suspicious for recurrence and provided with contact details for the CNS. They were assured they would receive an urgent clinical review should any concern be identified by the CNS and would not have to see their own GP to be reviewed by the gynaecology oncology team.

All patients received an annual telephone call by the CNS or their administrative assistant; this was part of the audit to ensure patient safety as this was a new initiative. The patients were asked a series of questions (Figure 1), which aimed to assess if they had any worrying symptoms or concerns. They were also asked if they had been back to the gynaecology clinic and their satisfaction with patient-led follow-up on a scale of 1–10. This phone call also acted as a reminder that the team were there to provide support should they need it. The phone calls also allowed the clinical team to check that the patients had the contact details of the nurses and that they still had the information pack on the signs of cancer recurrence. If the patient had lost either, the information was either given over the phone or sent in the post.

Data were collected in June 2018 and January 2019 for 104 patients operated on between November 2013 and January 2018. The data collected included patient age, date of surgery, completed questionnaires and any individual comments. The data were then analysed to assess patient satisfaction and symptoms suggestive of recurrence, and individual comments were noted. Electronic hospital notes were accessed to complete missing data and to see the outcome for those who came back to the clinic.

Findings

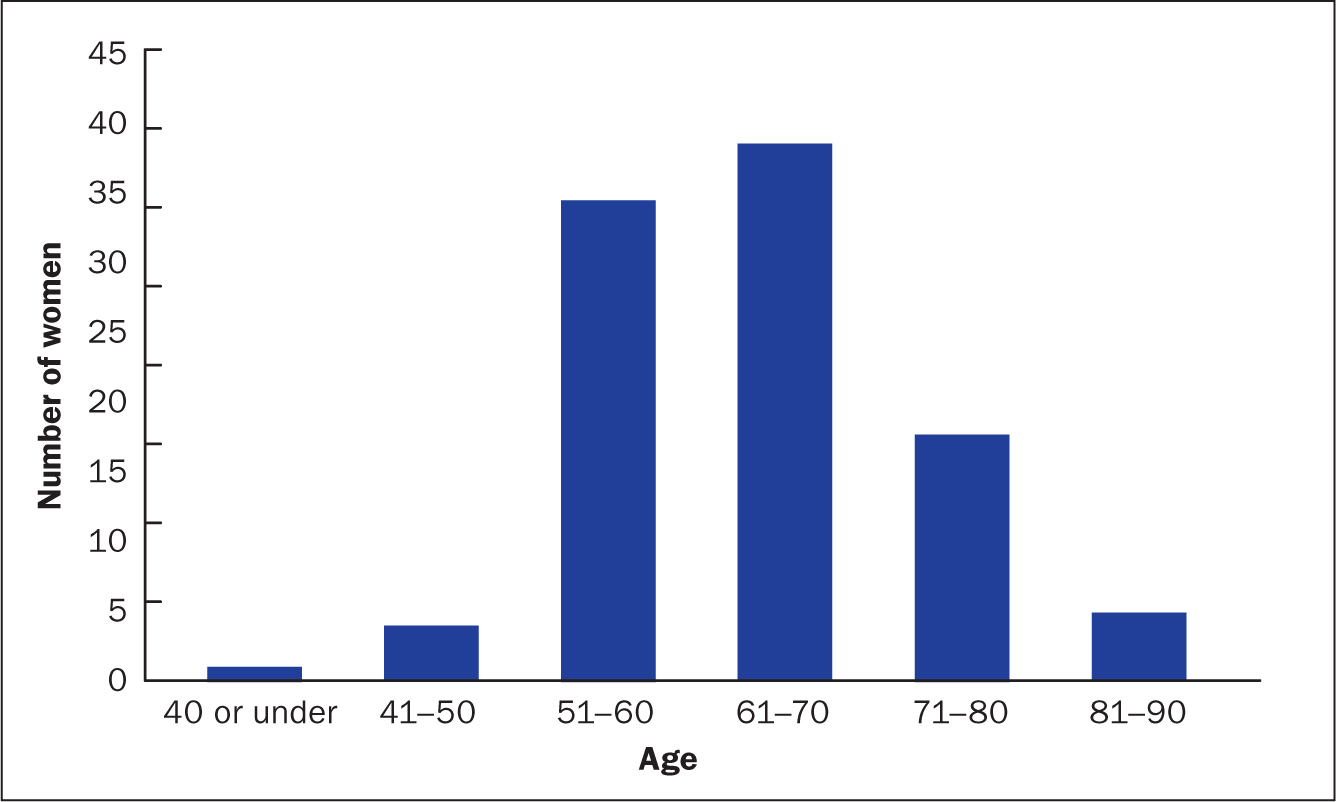

There were 104 women in the study population; 83 patients were white British, 3 were Asian, 2 were of mixed ethic origin and 16 did not disclose their ethnicity. Ages were in the range of 34-89 years, with most of the patients being aged 61-80 years (Figure 2). All of them accepted the patient-led follow-up pathway.

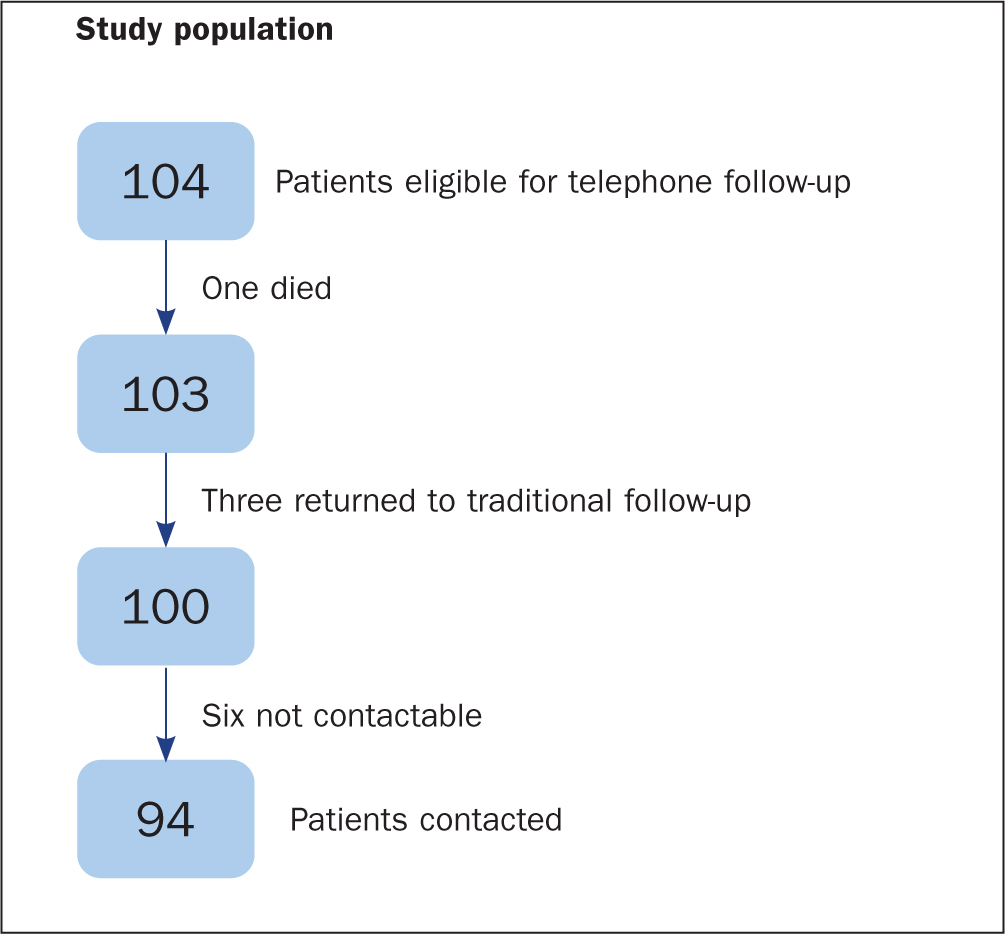

Out of 104 patients, one died within the first year of her follow-up due to a stroke. She was therefore not included in the total when the results were calculated. Six patients out of 103 could not be contacted after multiple attempts but the hospital electronic notes showed no evidence of any hospital attendance suggesting a recurrence. Three patients out of the remaining 97 went back onto the traditional follow-up as one patient required emotional support and the other had vulval soreness so requested to be seen more frequently; the third patient did not speak English so could not have had a telephone follow-up. The hospital records showed that none of these three patients had had any signs of cancer recurrence. Therefore, data were analysed for the remaining 94 patients (Figure 3).

Over 5 years, eight patients contacted the CNS team, while nine contacted their GP. Most contacts were made because patients experienced symptoms such as abdominal pain, bleeding, pelvic discomfort, or urinary and bowel problems, or for emotional support. Most of these self-resolved and many patients were reassured over the phone by the CNS. Nine of these patients were then reviewed in clinic but were not found to have a recurrence of cancer on examination. The hospital electronic records of six patients who could not be contacted showed no record of any hospital attendances. It is of course possible that these patients could have gone to other hospitals.

At the time of data analysis, 4 out of the 103 women had completed 5 years of follow-up, 31 were in their fifth year of follow-up, 22 were in their fourth year of follow-up, 30 in their third year of follow-up, and 16 in their second year.

A questionnaire was filled in annually for all patients and the results shown here (Table 1) are from the most recent phone call made to all study subjects. A majority of patients (78%) knew to contact the CNS with any concerns regarding their cancer. Eighteen women (19%) said they would contact their GP and three (3%) said they did not know who to contact if they had any concerns. Most (91%) had a contact number for the CNS, and 90% remembered symptoms suspicious for a recurrence. Many women who admitted to not remembering the symptoms of recurrence did acknowledge that they had all the information and leaflets given to them after surgery and would read them if they had any problems.

| Number of patients who: | Number of patients (n=94) |

|---|---|

| Knew to contact a health professional with any concern regarding their cancer | 91 (97%) |

| Would contact the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) about concerns | 73 (78%) |

| Would contact their GP about concerns | 18 (19%) |

| Had a contact number for the CNS | 86 (91%) |

| Remembered symptoms suspicious for recurrence | 85 (90%) |

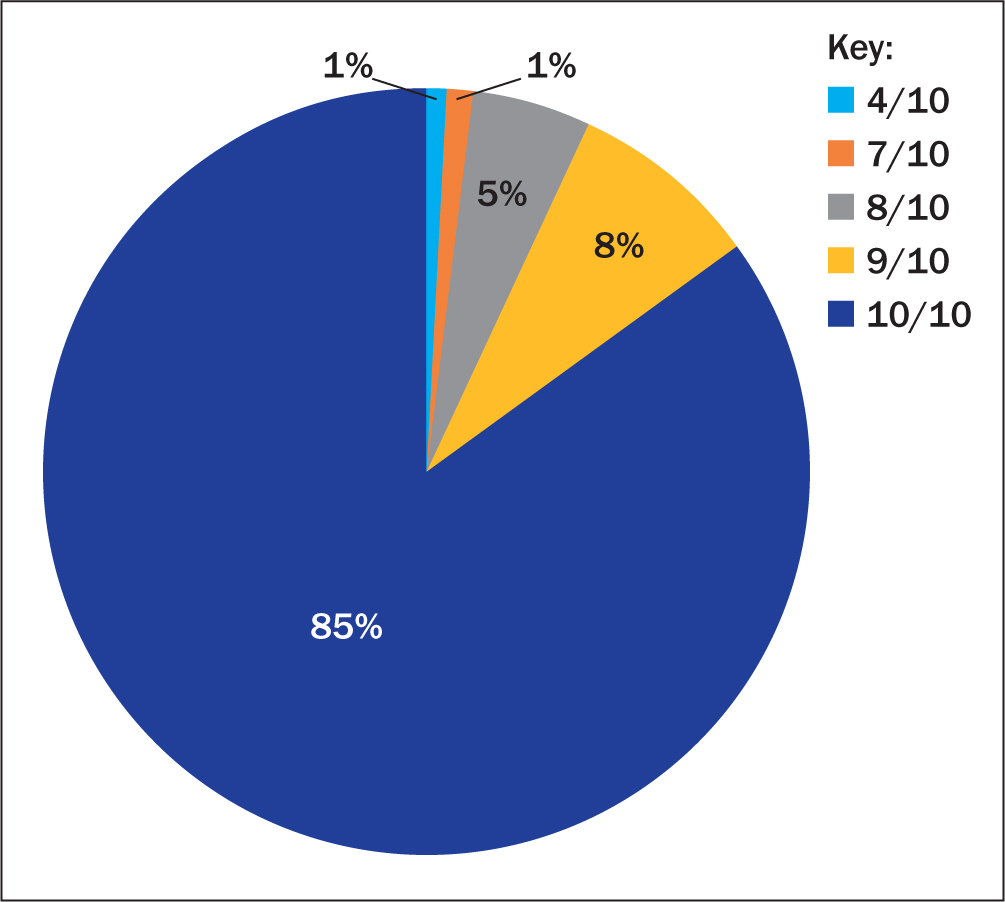

Some patients were contacted every year, but many patients have data missing for the years they were not contacted. Figure 4 shows the mean satisfaction score (rounded to the nearest digit) was calculated for 94 patients, irrespective of how many years of follow-up they had. Most women (85%) gave a satisfaction score of 10/10 every year that they were contacted. The only patient who rated the service 4/10 indicated that she would have preferred follow-up for reassurance but still preferred to contact her GP should she have any concerns.

On the satisfaction survey, 92% of patients scored 9/10 or 10/10. Many comments made by patients reflected the hypothesis the team had in 2013—that coming into hospital regularly is stressful, especially when they are not experiencing any symptoms. Quotes from patients include:

‘It's a lot better for me to not attend appointments as it causes me less stress.’

‘I get upset looking at the leaflets—will call if anything worrying. Coming to hospital would bring it all back and I would rather not think about it.’

‘The nurses were brilliant. I had 45 minutes longer than I would with a doctor so it was good as they could explain everything in detail.’

‘I would have liked more appointments with the consultant for reassurance.’

‘I'm a worrier and regular hospital appointments would worry me. Maybe a check-up at 5 years and be able to see a doctor but I'm perfectly happy. Thanks for the phone call, it has been reassuring.’

‘I was initially worried about not having a follow-up but, after the appointment with the nurse, I felt fine.’

‘I'm happy to be discharged and I know to contact the nurses if I have any problems.’

‘I appreciate the phone call but I expected it sooner.’

Two patients suggested a follow-up appointment after 3 or 5 years for additional reassurance. However, the majority were satisfied to be on the patient-led follow-up as they were happy to avoid a hospital appointment, because it would cause them anxiety and worry. Many patients said that, even though they had no problems, they appreciated the phone call and found it reassuring.

Discussion

Most women (85%) rated their satisfaction as 10/10 for every year of their follow-up and the majority of them were happy to contact the team if they needed to. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence in the patients on the new pathway.

Although there have been no recurrences in this study population, most of them have not completed a 5-year follow-up, which is the traditional length of time to calculate survival rates. However, the European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines state that ‘most recurrences will occur in the first 3 years after treatment’ (Colombo et al, 2013). This means that the 55% of women in this study who have already completed 3 years of follow-up are unlikely to have a recurrence.

Furthermore, as a result of reduced clinic follow-up appointments, the gynaecology service noted an increase in its capacity. This is because women on the patient-led follow-up pathway required nine fewer consultant appointments each over 5 years. This means that if 100 women were on the pathway, this would free up 900 appointments over a 5-year period.

In the first 18 months of the study, the nursing team did not find time to make phone calls because of their heavy clinical workload. Data collection started during the second year when an administrative assistant was employed. However, because of clinical commitments, the calls could not always be made as scheduled and, on other occasions, when the calls were made, patients were not always available, which meant further data were missing.

The questions were easy for the patient to complete and gave practitioners a clear understanding about how the patient was managing. However, it was felt some patients were answering the satisfaction question based on their entire treatment rather than on the telephone follow-up service specifically. It may have been better to have added a question on whether they preferred regular hospital appointments or the yearly phone call follow-up. The majority of patients were complimentary about the care they received from the gynaecology oncology team at the time of their initial diagnosis. This could have had an impact on the high rate of satisfaction with the service as they had high levels of trust in their doctor and CNS.

A study by Smits et al (2013) evaluated the effect of nurse-led telephone follow-up on patient satisfaction compared with conventional follow-up in women treated for endometrial cancer. Quality-of-life outcomes and satisfaction levels did not differ between both forms of follow-up. Nearly all women (98%) who had nurse-led follow-up found it an acceptable alternative to conventional follow-up.

A randomised control trial by Beaver et al (2017) in England evaluated the effectiveness of nurse-led telephone follow-up compared with the traditional hospital follow-up for patients with stage 1 endometrial cancer. The outcomes included psychological morbidity, patient satisfaction, quality of life and time to detection of recurrence. The results showed there was no significant difference between groups in satisfaction and there was no reported physical or psychological detriment.

The results of both these studies reflect the results from this study—that patient satisfaction is high with nurse-led telephone follow-up and that the likelihood of cancer recurrence is low.

Conclusion

The vast majority (92%) of patients scored ≥9 on the 10-point satisfaction survey and there has been no evidence of cancer recurrence on the patient-led pathway. This study has led to a change in practice and to the service provided. The data have been discussed with the regional Cancer Alliance and risk stratification is now being embedded into oncology follow-up. Patient-led follow-up for low-risk cancers is consequently being implemented in all the trusts in the Cancer Alliance.