The creation of an abdominal stoma for the discharge of bodily waste is a life-altering event. For many, the intervention is life saving and/or a relief from devastating symptoms of long-term gastrointestinal conditions such as Crohn's disease, inflammatory bowel disease and diverticulitis and diseases such as colorectal cancer (Formijne Jonkers et al, 2012; Abdalla et al, 2016; Herrinton et al, 2016).

While the benefits to the health of the person who has undergone the surgery is evident to the nurse, it is not always evident nor is it of similar value to the patient. For a nurse, success may be defined as when the underlying disease greatly improves or does not recur, or the patient is no longer readmitted to the hospital because of their underlying condition and is free of postsurgical complications (Formijne Jonkers et al, 2012; Abdalla et al, 2016; Herrinton et al, 2016).

However, for the patient, questions arise over whether the clinical benefit of the surgery correlates with their perception of health beyond the clinical outcome. The patient may judge the outcome based on their perception of satisfaction that results in increased functionality, social connectedness or health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Given this, the primary aim of this study was to understand how an ostomy population perceives their HRQoL beyond the clinical outcome. An in-depth view was gained of the quality of life (QoL) and wellbeing of a group of individuals living in the Netherlands who had undergone ostomy surgery, using the City of Hope National Medical Center Quality of Life Questionnaire for Patients with an Ostomy (COHQoL) (Grant, 2019). Secondary to this evaluation was an assessment of the key stressors known to influence HRQoL in this population (Pittman et al, 2008; Nybaek et al, 2010; Nichols and Inglese, 2018).

Study objectives

The purpose of this research was, first, to assess how an ostomy population in the Netherlands perceives their HRQoL and, second, to determine key stressors influencing HRQoL in these people.

Methods

Data collection

A cross-sectional survey assessed a proprietary database of patients, aged 18 years or older, who had ostomy surgery and who had access to email and lived in the Netherlands. Potential respondents were sent email invitations explaining the study, their rights and confidentiality, and a non-transferable link to the questionnaire. Opening the link and completing the questionnaire were considered as consent to participate. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were limited to age, excluding those under 18 years of age. Before the start of the study, ethical committee review was sought and waived by the Medical Ethical Commission of Maastricht UMC+ hospital.

Data collection began in the Netherlands on 15 January 2018 and closed on 1 March 2018. Of the 4500 patients invited to participate, 2127 responded, a 47.3% response rate and a margin of error of 2.1%.

The survey was assessed for: face validity—the degree to which the assessment appears effective in terms of stated aims; and content validity—whether the content included a representative sample of the domain to be measured. These are non-statistical assessments. Upon completion of the data collection, the survey was assessed for inter-item reliability and found to be reliable (Cronbach's alpha: 0.9157).

Health related quality of life (HRQoL)

This study captured two measures of HRQoL:

City of Hope National Medical Center Quality of Life Questionnaire for Patients With an Ostomy

The COHQoL has two components: the first consists of 47 forced-choice and open-ended items that concern sociodemographic characteristics as well as work, health insurance, sexual activity, psychological support, clothing, diet and daily ostomy care. The second component contains 43 QoL items using 10-point scales. It indexes attributes of physical, psychological, social and spiritual wellbeing as they relate to their ostomy.

Because the focus of this paper is on HRQoL as determined by the COHQoL survey, we report on the second component of the survey.

Visual Analogue Scale

Participants were also asked to reflect upon their QoL from a personal, more holistic, perspective. They were asked to consider the impact of their stoma system on their overall quality of life on a Visual Analogue Scale (VASQoL) of 1 to 100, where 1 equals the worst possible quality of life and 100 is the best possible quality of life.

Assessment of skin irritation

Participants provided their perception of skin integrity through a self-assessment of their peristomal skin. This assessment was reported through responses to two identical ordinal scale questions on their perceptions of the usual condition of their skin and its condition the last time they changed their skin barrier, which were devised and reported on by Nichols (2018) and Nichols and Inglese (2018). Ranking the cross-tabulated responses allowed for the determination of six categories of skin condition. This was further combined into four main definitions of skin condition:

Assessment of ostomy barrier leakage

Effluent leakage was determined via the yes/no question: ‘Have you experienced any leakage under your ostomy barrier in the last 4 weeks?’

Data analysis

The primary analyses of the data were descriptive in nature. Continuous variables were summarised via standard summary metrics (average, standard deviation, median etc). Categorical variables were summarised using frequency counts and proportions.

To investigate factors that influence HRQoL, statistical analyses were performed using generalised linear models for continuous dependent variables and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. A statistical model was used to assess each QoL variable to examine key stressors influencing HRQoL.

The statistical model was adjusted for the following respondent characteristics: age; sex; ostomy type; length of time a respondent had been living with their ostomy; whether the ostomy surgery was planned or expected; whether the ostomy was permanent or temporary; the condition of/severity of irritation to the peristomal skin; and the experience of leakage under the barrier. Statistical analysis were performed with SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Demographics

The study surveyed individuals living in the Netherlands who had undergone ostomy surgery. Approximately 99% of the participants said they were Dutch nationals.

Table 1 shows the group's demographics regarding sex, age, ostomy type, time since ostomy surgery, whether the surgery was planned or unexpected, and permanent versus temporary status. In this population, the majority had permanent stomas (90.5%), more than half (63.4%) were male, 56.5% had a colostomy, and 67.3% had surgery that was planned.

| Information | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of respondents | 1825 |

| Sex (male)* | 1148 (63.4) |

| Age (years)† | 64.7±9.9; 23–80 |

| Ostomy type | |

| Colostomy | 1031 (56.5) |

| Ileostomy | 425 (23.3) |

| Urostomy | 326 (17.9) |

| Multiple stomas or unknown | 43 (2.4) |

| Time since surgery (years); average ± SD; range§ | 6.6±8.1; 0–72 |

| Ostomy surgery|| | |

| Planned | 1209 (67.3) |

| Unexpected | 586 (32.7) |

| Ostomy duration¶ | |

| Permanent | 1648 (90.5) |

| Temporary | 116 (6.4) |

| Not yet known | 57 (3.1) |

Table 2 shows respondents' usual peristomal skin condition, and severity of irritation, as well as experience of effluent leakage under their ostomy barrier. More than half of the population (55%) indicated their peristomal skin usually has some degree of skin problem and 30% indicated that they experienced some leakage under their ostomy pouch barrier in the 4 weeks before they responded to the survey.

| Information collected | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of respondents | 1825 |

| State/severity of peristomal skin | |

| Normal (no irritation) | 813 (44.5) |

| Mild irritation | 584 (32.0) |

| Moderate irritation | 255 (14.0) |

| Severe irritation | 173 (9.5) |

| Experience of leakage under the ostomy barrier | |

| Yes | 543 (29.8) |

| No | 1282 (70.2) |

Health-related qualify of life

Table 3 presents a summary of the COHQoL and Visual Analogue Scale QoL. The sample sizes for each measure are different because some responses are missing; some of the respondents chose not to answer some questions.

| n | Average±SD | Range | 95% CI for average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City of Hope National Medical Center Quality of Life Questionnaire for Patients with an Ostomy | ||||

| Overall | 1041 | 7.0±1.3 | 1.2–9.3 | 6.9–7.1 |

| Domain specific | ||||

| Physical wellbeing | 1492 | 7.8±1.7 | 0.2–10 | 7.7–7.9 |

| Psychological wellbeing | 1622 | 6.8±1.1 | 2.3–9.5 | 6.7–6.8 |

| Social wellbeing | 1564 | 7.2±1.7 | 0.9–10 | 7.1–7.3 |

| Spiritual wellbeing | 1506 | 5.9±1.9 | 0–10 | 5.8–6.0 |

| Visual Analogue Scale quality of life scale | ||||

| 1801 | 75.3±18.0 | 1–100 | 74.5–76.1 | |

Key stressors influencing HRQoL

The statistical analysis indicates that results from both the COHQoL and VASQoL instruments used show the following are key stressors:

Respondent age was found to be positively associated with COHQoL (as respondent age increased, COHQoL also increased; P<0.01), but not VASQoL. Although age was not a key stressor in VASQoL, this analysis suggests that gender influences VASQoL (P<0.01) but not COHQoL. Males were found to have marginal but significantly greater average VASQoL than females (74.5 vs 71.5).

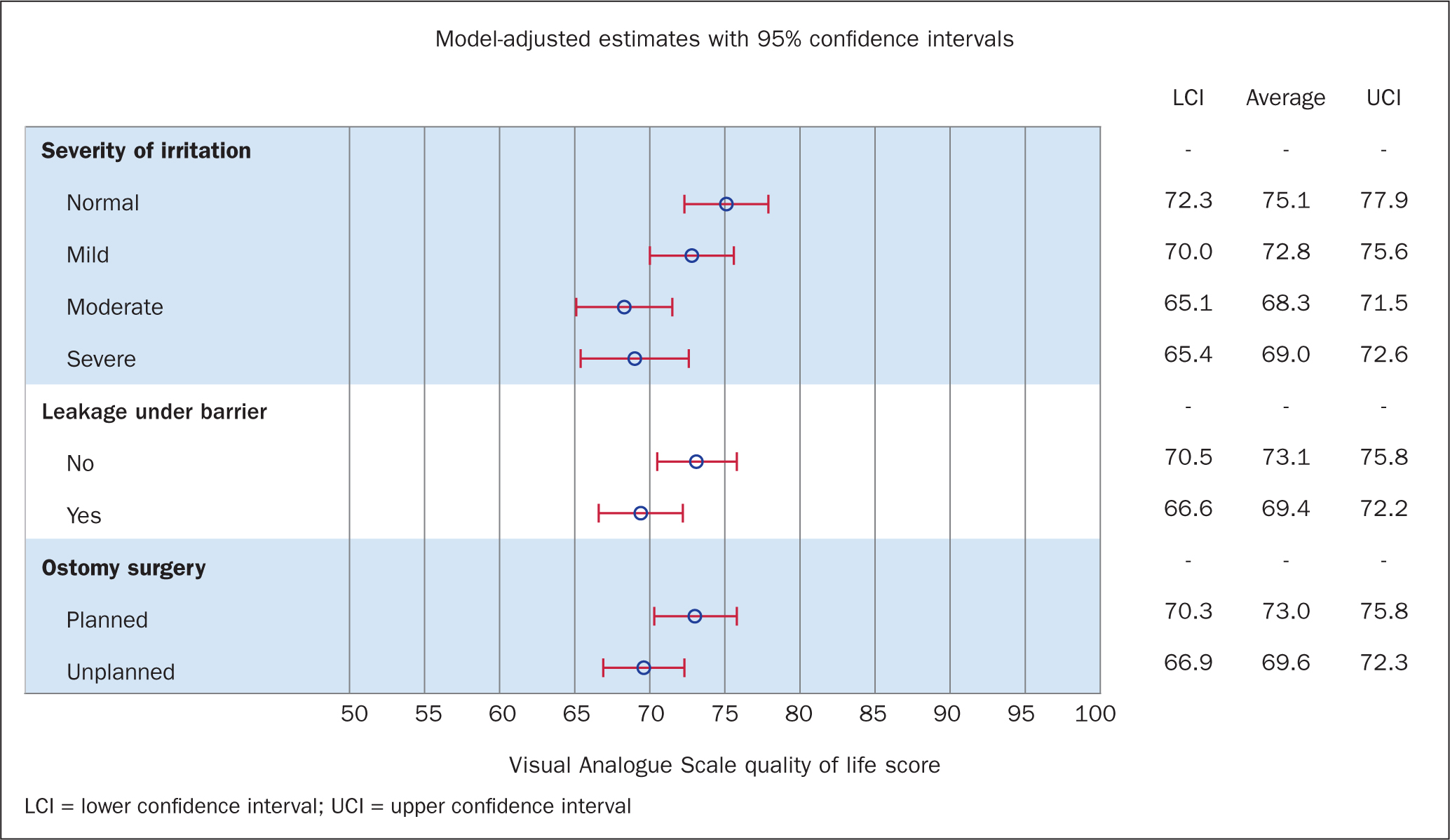

The condition of the peristomal skin, experience of leakage and whether an ostomy was planned are associated with the reported HRQoL. As the condition or severity of irritation of peristomal skin deteriorates, so does their HRQoL. Similarly, participants who said they experienced leakage under the ostomy barrier were found to have an associated decrease in QoL. Furthermore, participants whose ostomy surgery had not been planned had a lower QoL than those whose surgery had been planned. Figures 1 and 2 show the effect size (ie the magnitude) the three shared key drivers have on COHQoL and VASQoL respectively.

Figure 1 shows the shared key stressors influencing COHQoL. Respondents who reported normal peristomal skin had significantly higher average COHQoL scores than those with severely irritated skin (normal skin COHQoL=7.2; severe irritation COHQoL=6.4; P<0.01). No significant difference in COHQoL between those with moderate and severe skin conditions was noted. Leakage under the barrier was associated with a COHQoL score approximately 0.5 points lower (P<0.01), and unplanned ostomy surgery was associated with a COHQoL score approximately 0.3 points lower (P<0.01).

Figure 2 shows the shared key stressors influencing VASQoL. As with COHQoL, severity of irritation is associated with a decrease in QoL (P<0.01). Respondents who reported normal peristomal skin had significantly greater average VASQoL scores than those who reported severely irritated skin (normal skin VASQoL=75.1; severe irritation VASQoL=69.0; P<0.01). Leakage under the barrier was associated with an approximately 4-point lower VASQoL (P<0.01) score, and unplanned ostomy surgery was associated with a VASQoL that was around 4 points lower (P<0.01).

Incidence of leakage and skin irritation

Table 4 tabulates leakage with skin severity. Seventy per cent of patients (1282 of 1825) reported they had not experienced leakage under their ostomy barrier in the previous 4 weeks. Of the 543 participants reporting leakage, 54.0% experienced some form of skin irritation. Of the 1282 participants who did not report leakage, 31.7% experienced some form of skin irritation. While people who reported leakage under their barrier were more likely to experience some form of skin irritation (OR 2.5; 95% CI (2.1–3.1); P<0.001), skin irritation occurred in both those with and without leakage.

| Severity of effect on skin | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Leakage under the barrier | Mild/moderate/severe n (%) | None n (%) | Total |

| Yes | 293 (54.0) | 250 (46.0) | 543 (29.8) |

| No | 407 (31.7) | 875 (68.3) | 1282 (70.2) |

| Total | 700 (38.4) | 1125 (61.6) | 1825 (100) |

Discussion

This cross-sectional evaluation is the first large-scale study to examine HRQoL in individuals with an ostomy residing in the Netherlands using the City of Hope QoL questionnaire.

HRQoL is a dynamic measurement that changes with an individual's circumstances and their adjustment and/or acceptance of the state of their health over time (Karimi and Brazier, 2016). This study's findings show that HRQoL in the Netherlands for people with an ostomy is similar to that in other countries. HRQoL scores are consistent with previous research using the COHQoL survey (Pittman et al, 2008). Our findings are also consistent with a previous study examining the QoL of ostomates in Canada (average QoL=72.3), the UK (74.4), and the US (75.3), which used the SF36v2, a generic HRQoL instrument (not specific to people with an ostomy) to assess QoL (Nichols et al, 2019).

Moreover, while people with an ostomy have a generally positive HRQoL, there are consistent key stressors that affect this. The literature has indicated that peristomal skin problems, leakage, and difficulty in adjusting are key predictors influencing an ostomate's HRQoL (Pittman et al, 2008; Krouse et al, 2009; Nybaek et al, 2010; Davis et al, 2011; Nichols, 2015; 2016; Maydick, 2016; Vonk-Klaassen et al, 2016; Verweij et al, 2017; Nichols and Inglese, 2018). Our analyses are in line with published literature as this study found that HRQoL is influenced by peristomal leakage, peristomal skin irritation, whether the ostomy surgery was planned and, to a lesser degree, age and sex, as measured by COHQoL and VASQoL.

Patients with access to nurses who specialise in supporting people with ostomy needs and trained to address these key stressors have the opportunity to achieve a positive and enriched HRQoL as they transition and continue through life with a stoma.

A common health stressor within the first 3 months of surgery is irritated peristomal skin (Salvadalena, 2013; Taneja et al, 2017; 2019), which has been reported to be as high as 70% in some ostomy populations (Salvadalena, 2008; 2013; Gray et al, 2013; Lindholm et al, 2013). Additionally, early recognition and management of peristomal skin conditions may help to lower stoma-related healthcare costs (Meisner et al, 2012; Neil et al, 2016; Taneja et al, 2017; 2019). Researchers have referred to the additional benefits of post-surgical support by specialist nurses. When individuals seek guidance or care, many organisations may also be available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and will provide a personal contact at every call (Nagle et al, 2012; Rojanasarot, 2018).

New and established ostomates may request home visits by a specialist nurse if they experience complications with their stoma or peristomal skin. Specialist nurses will tailor care to individuals and provide products that best address their needs, including those that are formulated to support optimal skin health, such as ostomy skin barriers that are infused with ceramide or have pH buffering technology (Colwell et al, 2018; McPhail et al, 2018). Access to clinical services and products to support skin health are central to maximising clinical outcomes as well as an individual's HRQoL.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

By eliciting responses directly from people with an ostomy, this study provided insights into how they perceive their HRQoL beyond the clinical outcomes of ostomy surgery. Given the obvious sensitive and personal nature of the questionnaire, participants could respond through an anonymised survey platform, to make providing answers less uncomfortable. This resulted in a greater response rate than would have been expected with an interviewer-administered questionnaire.

Limitations

Data were collected using a cross-sectional survey, where participants provided their perception of skin integrity through a self-assessment of their peristomal skin and a 4-week recall of leakage. Associations with key stressors affecting HRQoL measures are based on respondents' perceptions of their skin integrity and ability to accurately recall peristomal leakage. As such, this study cannot rule out the possibility that participants did not know they were experiencing leakage. Moreover, although the associations found between the key stressors and HRQoL are suggestive of overall influence, the cause and effect of these stressors cannot be determined.

Finally, our analysis did not report on non-scaled domains within the COHQoL, including marital status, work, household income, health insurance, sexual activity, psychological support and diet (Krouse et al, 2009; Grant, 2019).

Conclusion

The ostomy population for this study lives in the Netherlands. The cross-sectional survey assesses the health status of individuals who, in a healthcare environment similar to that in many European countries, have access to health insurance providing access to a national network of hospitals and home health services.

While peristomal skin irritation may be expected in the period immediately following surgery, it is interesting to note that within this population of established ostomates (average 6 years post-surgery), leakage and skin irritation persist, which shows these are important issues that must be continually addressed.

Medical services in the Netherlands are equipped with qualified specialist nurses who are ready to assist patients in all aspects of their care including, but not limited to, providing education, medical supplies and care for patients with an ostomy. Individuals with access to specialist nurse support and products designed to prevent leakage and prevent skin irritation may be able to maximise their individual health status, even while transitioning and continuing their life with a stoma.