The first phase of the COVID-19 global pandemic had a significant impact on student nurses studying in the UK, heralding profound changes to their lives (Bates, 2020; Ford, 2020). In terms of their education, the most striking of these was the emergency measures implemented by Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) regulators (NMC, 2020), which provided nursing students in their final 6 months of study with the opportunity of completing a paid consolidation placement. These emergency measures were later replaced (NMC, 2021). This presented significant challenges for learners, universities and placement providers (Ford, 2020). This study explores the experiences of adult nursing students who completed their final clinical placement during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background

The first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic subjected health and social care systems around the world to unprecedented pressure (Department of Health and Social Care, 2020). In order to meet service demand, the UK launched a series of initiatives to increase the number of healthcare workers available to maintain NHS services, including caring for those infected with the virus. One such innovation involved offering final year nursing students the option of undertaking an extended final placement to support the delivery of care (Swift et al, 2020).

Nursing students move between their university and different parts of the health sector when undertaking their studies to facilitate development of a competent practitioner. Traditionally, clinical placements prioritise students' learning needs rather than operational health needs (Cantos et al, 2015); consequently, students are supernumerary and are not considered part of the workforce establishment. In response to COVID-19 pressures, the extended final placement had an alternative approach, as student nurses became more integral to staffing rosters (Hayter and Jackson, 2020).

Universities and healthcare providers have support mechanisms in place to enhance student learning; they can include practice assessors, practice education facilitators and academic assessors. These all enhance the learning of the student by helping them draw meaning from events that occur in the clinical environment and allow the early identification and remediation of any issues that students encounter in the clinical setting (Naicker and Rensburg, 2018). However, this existing structure is designed to support students completing a supernumerary placement. This study explored the experiences of students during the period of their final placements when they were part of the nursing workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aims of the study

The study aimed to explore the experiences of final year nursing students who completed their final clinical placement during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Method

Design

A phenomenological approach, as defined by Bryman (2016), was used to inform the study's design to gain insight into the student's lived experience. The focus was to obtain detailed accounts from individuals about their perception of the phenomenon being investigated, therefore, data collection included semi-structured interviews.

Participants and data collection

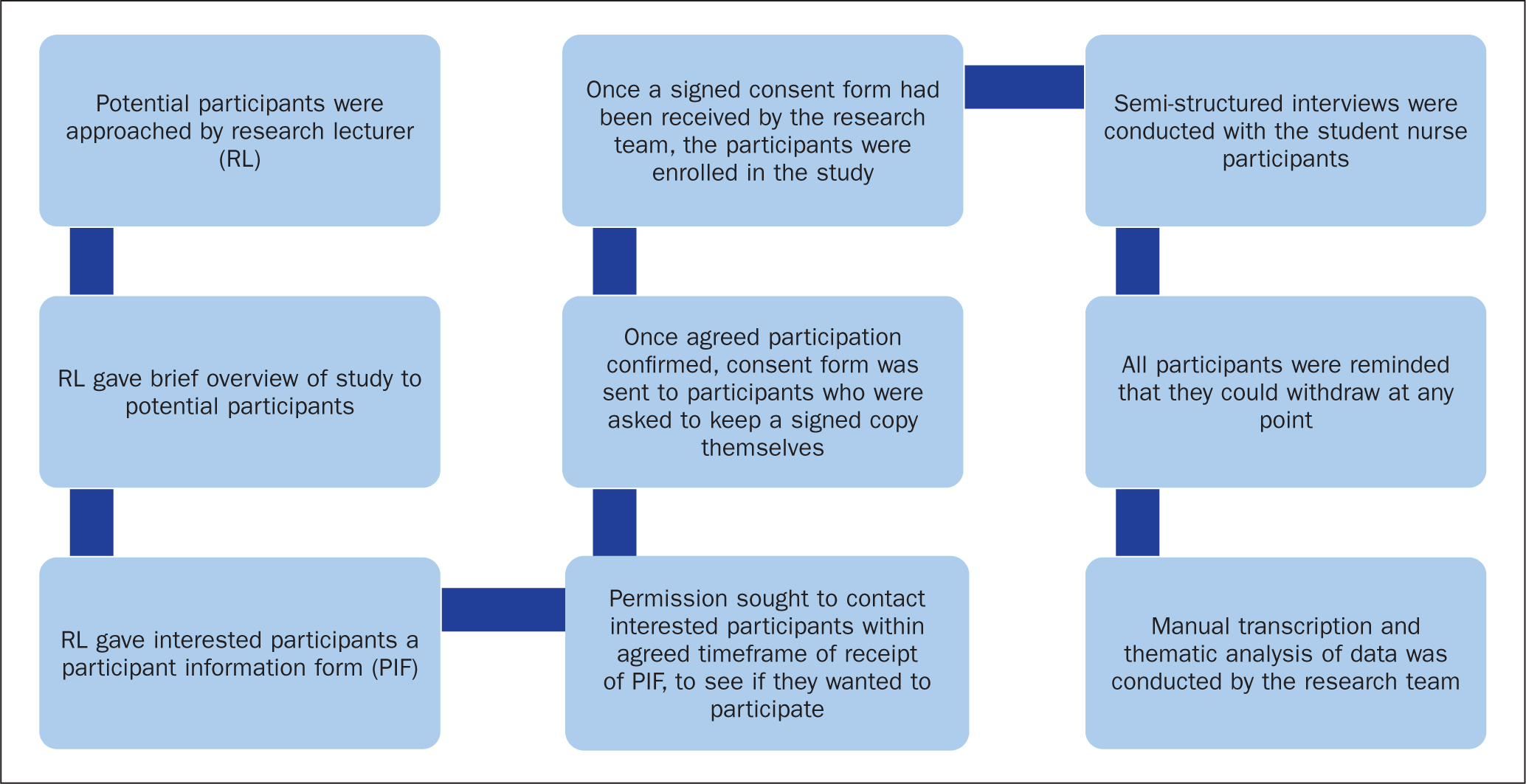

There were a number of issues considered when determining the sample size, one of which included the heterogeneity of the population. Following ethical approval, a purposive sample was chosen for this study as the population to be studied was reasonably homogeneous. Ten participants were recruited, which comprised 10 student nurses, representing 20% of the cohort year. The recruitment and consent process are detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Recruitment and consent process

Figure 1. Recruitment and consent process

The students participated in individual semi-structured interviews that were conducted using a schedule of nine questions and were based on the objectives of the study (see Box 1).

Box 1.Schedule of questions for students

- How has it been for you working in your final placement?

- What does it feel like working in a non-supernumerary capacity?

- How do you manage the challenges of student/employee status?

- How well supported do you feel during your placement?

- How does it feel to be paid for your extended placement?

- How have you changed/adapted to this exceptional environment during the COVID-19 placement?

- What lessons are you learning during this period of your training?

- Do you feel that your contribution to the workforce makes a difference in the delivery of care? If so, can you give some examples? If you feel that it does not, why not?

- What else would you like to share about your experience/placement?

The students' ages varied from 22 to 50 years. There were nine females and one male, seven of the students were of white British ethnicity and three from a black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) background. The demographic data for the participants is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographics of participants

| Students | Age group | Sex | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30−40 | F | BAME |

| 2 | 30−40 | F | White |

| 3 | 20−30 | F | White |

| 4 | 20−30 | M | White |

| 5 | 20−30 | F | White |

| 6 | 20−30 | F | White |

| 7 | 40−50 | F | BAME |

| 8 | 40−50 | F | BAME |

| 9 | 20−30 | F | White |

| 10 | 40−50 | F | White |

The majority of the students completed their placement in regional and metropolitan acute teaching hospitals, and a smaller number in the community setting; they were all enrolled at the same university. The diversification of placement allocations, age, sex and ethnicity was representative of the university student cohort as a whole.

Data collection took place between July and September 2020, while students were still on placements, via Microsoft Teams. The interviews were conducted by the project lead and research team members.

Data analysis

Data analysis was undertaken using the framework developed by the National Centre for Social Research (cited in Ritchie and Spencer, 2002).

All interviews were transcribed and returned to the participants to ensure that they were a true record of discussions. Minor revisions were made as requested.

The research team listened to the transcription recordings independently and agreed data analysis would take place through establishing a thematic framework by revisiting the aims of the study while looking at the emergent issues. The data were annotated manually and, from this, a range of experiences for each theme was considered. After discussion, themes were agreed.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from the authors' university ethics committee. The researchers ensured that they upheld the domains of the Research Governance Framework (Health Research Authority, 2021) and adhered to the principles of the Data Protection Act, 2018.

Findings

Following the researchers' analysis of the data, three main themes emerged:

- The importance of support mechanisms

- Developing confidence in clinical practice

- Innovative learning opportunities.

Theme 1. The importance of support mechanisms

This category represents the students' perceptions of their physical and mental wellbeing with respect to their working environment and identifies the value participants placed on having robust support mechanisms in place.

During data collection it became clear that the students experienced a heightened state of stress and anxiety during the extended placement. One of the participants said:

‘Before I started, I was really nervous. I didn't know what to expect, but the induction I had helped a lot.’

SN1

Another student spoke of their distress at the delay in resuscitating patients due to enhanced infection control protocols:

‘I found it really hard. As a nurse you are taught to do everything in your power to save your patient … and you just have to wait until someone comes in with the full [personal protective equipment (PPE)]. That one took my head a long time to get around.’

SN2

Apart from the stress associated with their placement, students expressed concerns about their family's wellbeing. It was reported that some were concerned about working with ‘potentially infected and vulnerable groups’ and taking the infection home to their families. This was one of the main concerns that needed to be addressed on the induction programmes:

‘I was petrified of taking the virus home to my mother, she was in the vulnerable group, and the media coverage made it much scarier than the reality. The magnitude of it was bigger in London than it was in [the local area].’

SN3

There are normally robust support mechanisms available during student placements; however, this extended placement during the pandemic placed extra stress and pressure on the individual students, clinical and academic staff.

During data analysis it became apparent that students needed significant support to manage their anxieties. They identified that there were different and more enhanced support mechanisms available to them than there had been in the past. They said this support came from staff at the university as well as clinical practice.

‘Before I started, I was really nervous, I wasn't sure what to expect, I thought we would be allocated our ward and left to it but that was not the case, we were very well supported by everybody.’

SN4

They described support as being:

‘Always present, ensuring that we were getting all that was needed on the wards and that we were getting our papers [practice competency documents] signed.’

SN5

Participants recognised that there was some confusion about the role and responsibilities of the student while also being an employee. Some healthcare assistants (HCAs) were reluctant to accept delegation from the student nurses. These incidents and ‘moments of hostility’ were reported early on in the placement and were soon resolved by discussion and support from their practice education facilitators (PEFs).

Theme 2. Developing confidence in clinical practice

As they completed the extended placement, students reported experiencing a growth in confidence.

‘I feel my confidence has grown, I have started to believe in myself a little more, I'm playing a much more valued role within the team and my advice on patient care is acknowledged.’

SN2

‘The longevity of time I had in practice has helped me feel better prepared and more confident to transition into my role as a registered nurse.’

SN6

‘I felt more empowered and confident, normally, as a student when a doctor asks you a question you get the registered nurse to answer, but, on this placement, I answered all the questions.’

SN7

‘There was some confusion initially about our role, especially from healthcare assistants, they treated us with some hostility and would not accept delegation from us; however, with support from our PEFs and as our confidence grew, this got much better.’

SN8

One student described how the ward was short-staffed and the manager required a registered nurse from another ward to help out, but the student insisted that she fill the gap in the roster stating:

‘I said: “I'll do it. I'd like to manage the bay; this is what my placement is for”, and I think having to do this gave me a lot of confidence, having to step up, and I think I learned better when I just had to get on with it.’

SN9

In community settings, when it was safe to do so, the students were required to do lone visits to patients. One student said:

‘I have gained more confidence and feel much more confident since taking on a caseload and doing the visits on my own.’

SN1

One of the students said:

‘I have really enjoyed it. If I hadn't opted in, I would have really regretted it; I am enjoying every bit of it.’

SN7

The transition from student to registered nurse can be regarded as presenting challenges and arousing feelings such as fear, uncertainty, and anxiety (Health Education England (HEE), 2018). However, the students interviewed in this study suggested that the extended placement may have helped them to transition more easily. During this time students reported feeling a much greater part of the clinical team than ever before. One student's typical description was how:

‘Working as student/employee was better than being pampered as a student. It gives you confidence. You know your facts. You have to give the doctor a handover and not rely upon the (qualified) nurse.’

SN10

Another student said:

‘They [the multidisciplinary team] trusted my judgement, which was really great.’

SN7

One of the biggest challenges mentioned throughout the interviews was with PPE. Students said ‘the policies kept changing and were difficult to keep up with’, while others described the difficulty with ‘donning and doffing each day’.

In the acute settings especially, a typical comment was:

‘Everybody's identity was obscured by wearing PPE which created a surreal atmosphere.’

SN1

A typical suggestion was that:

‘This improved the team dynamic, reduced hierarchical structures which promoted a more collaborative way of working in delivering patient care.’

SN10

The students said that, although as challenging as wearing PPE was, their inclusion in the team, and the consideration of their opinion as a valuable contribution to patient care, had helped them with the transition to becoming a registered nurse.

‘My opinion mattered and members of the multidisciplinary team listened to what I had to say about patient care.’

SN3

Theme 3. Innovative learning opportunities

The students reported that completing a placement during a pandemic provided them with a valuable range of learning opportunities

They described how the responsibility of working in a non-supernumerary capacity enabled them to develop confidence in managing their own caseload. As they were responsible for the care they provided, the students said they gained an improved understanding of what it meant to be a full member of the clinical team. One of the students interviewed said:

‘I have learnt to manage my time more effectively as well as learning how to be more resilient. I think this pandemic placement has escalated my learning. It has been a steep learning curve, but it's one I am glad I have been through.’

SN7

In addition, due to social distancing requirements, the student nurses described increasing mastery of virtual communication platforms. Narratives shared included:

‘I had mastered and recognised the value of using virtual platforms to communicate and to learn and have realised my readiness for the transition to a registered nurse.’

SN3

‘I have learned how to do presentations on PowerPoint much better, I also found the contact with the PEFs and the academics through Microsoft Teams really useful, it has also helped me realise how ready I am to take on my role as a registered nurse.’

SN9

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to gain understanding of the students' experience of their extended clinical placement during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has been reported widely as having significant physical, mental and psychological impact on people worldwide (Bareket-Bojmel et al, 2020; Wang et al, 2020), and this has also been evidenced from the accounts and discussions with participants of this study.

The NHS People Plan (NHS England/NHS Improvement and HEE, 2020) emphasises the need for everybody to acknowledge the impact of working in stressful environments and suggests that a co-ordinated approach needs to be adapted to improve the support for individuals' health and wellbeing. The findings from this study suggest that this was evident throughout the student placement as students received support from several sources. This enabled them to grow and develop in confidence (Panduragan et al, 2011; NMC, 2019).

When entering the clinical practice environment, it is common for student nurses to be confronted with many challenges that may be unsettling and disrupt learning (Najafi et al, 2019), resulting in a ‘placement anxiety’. This is a phenomenon that has been defined as ‘a vague, perceived threat to a student's goals or expectations in clinical practice, due to the presence of stressors, including unfamiliar environments or situations’ (Simpson and Sawatzky, 2020). It has been suggested that a failure to effectively manage such feelings can negatively impact students' skills development and confidence (Ulenaers et al, 2021). It is also widely recognised that a student nurse's final placement plays an integral role in their confidence development (Panduragan et al, 2011; Carman et al, 2017) and this facilitates their transition to registered nurse status. In many respects, it could be suggested that the experience of the participants completing the extended placement align with those of a third-year student nurse completing a more traditional final placement. However, this study found strong evidence that the context in which the ‘COVID-19 generation’ of student nurses completed their studies must be taken into consideration in the discussion of findings.

It can be argued that completing an extended placement during a global pandemic has the potential for these challenges to be felt more acutely, with the threat of ‘unfamiliar environments and situations’ increasing significantly and a clear threat being presented to student development. The concerns expressed about the students' own families’ wellbeing and risk of COVID-19 exposure, is a sentiment that has also been recognised in wider research (Bareket-Bojmel et al, 2020; Wang et al, 2020), and is a clear example of the additional pressures this cohort of learners experienced.

One of the most striking findings from this research is that the enhanced expectations placed on students, such as taking full accountability for care delivery, assisted their professional development and ability to cope. This is particularly evident in the case of participants working in clinical teams during a period of heightened anxiety which aided team cohesion and their confidence. Interestingly, this study found that few of the students reported feeling anxious or upset about caring for patients towards the end of life, reflecting the findings of Harder et al (2020). This can be framed as the result of the increased sense of belonging experienced by participants.

It has been recognised that clear communication of what students can expect while on clinical placement is essential to ease placement anxiety in pre-COVID-19 times (Royal College of Nursing, 2017; George et al, 2020). The need for clear and transparent communication regarding placements was never more critical than when dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic (Health and Care Professions Council, 2020; Shanafelt et al, 2020). The complexity of the extended placement meant that there needed to be robust communication processes in place to avoid confusion. A variety of communication strategies were used to keep in touch, with virtual platforms being most common. It was observed that capability in using the technology proved to be a significant learning curve for all participants.

Despite the challenges the students experienced during their final placement they reported many benefits. These included greater integration within clinical teams, increased ownership of practice learning (NMC, 2019) and enhanced support mechanisms. Despite the significant ‘placement anxiety’ that the student nurses experienced, they felt empowered and respected for their contribution and demonstrated greater motivation to deliver high-quality care, as well as feeling more confident in their roles.

Recommendations for approved education institutions and placement providers

- Approved education institutions (AEIs) and placement providers should continue to use virtual platforms to offer students support where appropriate

- Placement providers should proactively seek to integrate final placement students into their clinical teams to improve the transition to registrant

- High priority should be given to clear communication when outlining placement expectations

- The impact and anxiety produced by the COVID-19 pandemic will cast a long shadow. AEIs and placement providers should be mindful of the implications of this on health care students.

Conclusion

This study explored the experiences of final-year nursing students who opted to complete their final clinical practice placement in a paid capacity during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings suggest that the students found the external placement to be a positive experience, were well supported and that the COVID-19-related stressors resulted in improved team cohesion and integration. The students had opportunities for learning that enabled them to enhance their clinical skills and they reported feeling more confident in their transition to being registered nurses. The use of virtual platforms was embraced by the students and proved an essential method of supportive communication, academic assessment and reflective discussion.

KEY POINTS

- The final-year students who took part in their final placements during the COVID-19 pandemic enjoyed their placements, although there was early confusion about their student/employee status

- Students felt well supported and were integrated into clinical teams, and had opportunities for learning that enabled them to enhance their clinical skills

- The use of virtual platforms was embraced by the students and proved an essential method of supportive communication, academic assessment and reflective discussion

- Students reported feeling more confident in their transition to registered nurse status

CPD reflective questions

- How do you facilitate student nurses' learning in the workplace?

- What support mechanisms do you use to encourage students to achieve their assessment outcomes?

- What do you think are the benefits and challenges of using virtual platforms to support students in practice?