At The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, the level of harm caused to a patient by a hospital-acquired pressure ulcer (HAPU) is determined by the attending tissue viability nurse on an individual patient basis. This decision is made following a holistic, person-centred assessment and is guided by the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) level of harm. The NRLS is the national database that collects patient safety incident data from NHS organisations across England and Wales (NHS Improvement, 2018a). The database has five levels of patient harm: no harm, low harm, moderate harm, severe harm and death (NHS Improvement, 2018a) (Box 1). The level of harm should not be apportioned based on the category of the pressure ulcer (PU) (NHS Improvement, 2019). These guidelines apply in NHS England and are not current practice in other areas of the UK. It is recognised that this clinical decision and interpretation of the NRLS levels of harm in the context of PU can be subjective. Although this creates additional demand on the tissue viability nursing service, the reliability of this assessment is improved and organisational assurance is achieved with this approach.

Box 1.National Reporting and Learning System levels of harm

- No harm—a situation where no harm occurred: either a prevented patient safety incident or a no-harm incident

- Low harm—any unexpected or unintended incident that required extra observation or minor treatment, and caused minimal harm to one or more persons

- Moderate harm—any unexpected or unintended incident that resulted in further treatment, possible surgical intervention, cancelling of treatment, or transfer to another area, and that caused short-term harm to one or more persons

- Severe harm—any unexpected or unintended incident that caused permanent or long-term harm to one or more persons

- Death—any unexpected or unintended event that caused the death of one or more persons

Source: NHS Improvement, 2018a

The author supports this person-centred approach for the reason that a PU can affect a patient to varying degrees. For example, a very small category 3 PU can have little to no impact for one patient, whereas for another patient a category 2 PU may cause considerable pain, infection and have a significantly detrimental effect on activities of daily living, quality of life and body image (Gefen et al, 2020).

The purpose of this article is to extract cumulative learning from 1 year of data on low-harm HAPUs in order to inform harm-free care and quality improvement strategies.

Root cause analysis

Not all NHS organisations perform root cause analysis (RCA) investigations for low-harm HAPUs. However, in the author's experience, organisations that embrace all available learning from these incidents are much better placed to prevent moderate-harm HAPUs and reduce future incidence of low-harm HAPUs. This improves patient outcomes and the patient experience and subsequently ensures cost-effective care delivery.

The practice of mini-RCA investigations for all low-harm HAPUs was introduced at the Royal Marsden in April 2018 (excluding category 1 PU). This practice became commonplace by May 2019. Mini-RCAs are completed by ward managers, supported by the lead nurse for harm-free care and tissue viability.

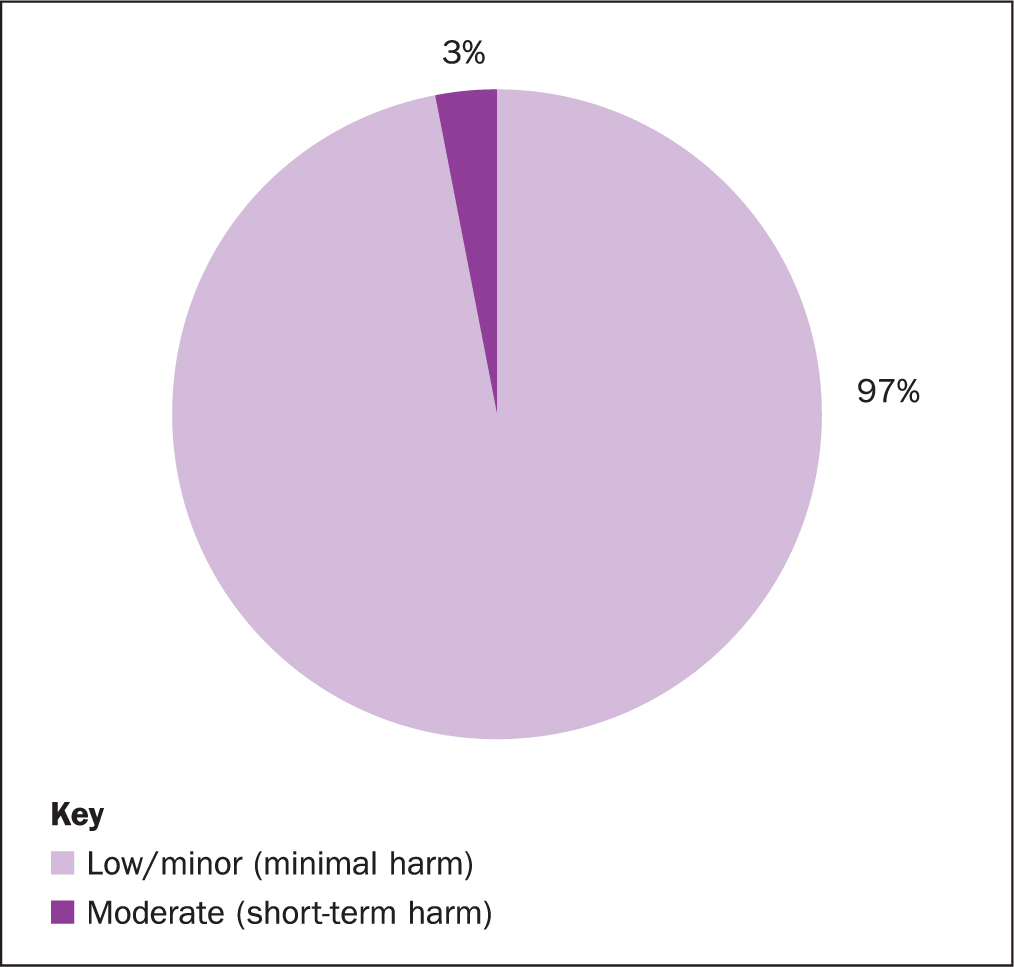

From April 2019 to March 2020 there were 108 HAPUs at the Royal Marsden, of which 3% were moderate harm (n=3) and 97% were low harm (n=105) (Figure 1). The most prevalent category of PU was category 2 (n=61) followed by category 1 (n=23) and suspected deep tissue injury (DTI) (n=14) (Table 1).

Table 1. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers (HAPU)

| Category of HAPU | Number |

|---|---|

| Acquired category 1 | 23 |

| Acquired category 2 | 61 |

| Acquired category 3 | 3 |

| Acquired category 4 | 1 |

| Acquired suspected deep tissue injury (DTI) | 14 |

| Acquired unstageable | 4 |

| Deterioration to category 3 | 1 |

| Deterioration to category 4 | 1 |

| Total | 108 |

Two of the three moderate-harm HAPUs were found to be deterioration of existing PUs. The third was an acquired category 4. The three moderate-harm PUs had a full RCA completed. At the Royal Marsden, all moderate-harm HAPUs are subject to an extended governance process where a full RCA investigation is presented at a panel meeting, consisting of staff from the multidisciplinary team and chaired by the chief nursing team. Moderate-harm HAPUs will not be explored in this article.

Of the 105 low-harm HAPUs, 23 were category 1, and so were not included in the mandatory mini-RCA investigation or for analysis in this paper; 1 low-harm category 2 PU was included in the full RCA process rather than the mini-RCA because it developed on the same patient as the acquired category 4 PU. Of the 81 low-harm HAPUs, 10 did not have a mini-RCA investigation (Table 2). Of the 10 mini RCAs that were not completed, 6 were related to a device, including patients' reading glasses and hearing aids.

Table 2. Root-cause analysis completion rate

| Category of HAPU | Full RCA | Mini RCA completed | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | No | Yes | |||

| Acquired category 1 | 23 | 23 | |||

| Acquired category 2 | 1 | 8 | 52 | 61 | |

| Acquired category 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Acquired category 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Acquired suspected deep tissue injury (DTI) | 1 | 13 | 14 | ||

| Acquired unstageable | 4 | 4 | |||

| Deterioration to category 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Deterioration to category 4 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Total | 4 | 23 | 10 | 71 | 108 |

Device-related HAPUs

NHS Improvement (2018b) updated the definition of a pressure ulcer for the NHS in England as:

‘Localised damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue, usually over a bony prominence (or related to a medical or other device), resulting from sustained pressure (including pressure associated with shear). The damage can be present as intact skin or an open ulcer and may be painful.’

This new definition brought about a shift from reporting HAPUs caused by medical devices towards also including non-medical devices such as an armchair. This change would likely lead to an increase in recorded HAPUs nationally but with the cessation of the national data-collection tool, the Safety Thermometer, in 2020, there is currently no method to monitor the longer term effects of this policy change.

Internationally, device-related pressure ulcers (DRPUs) can account for up to 81% of all HAPUs, most of which are related to respiratory support (Gefen et al, 2020).

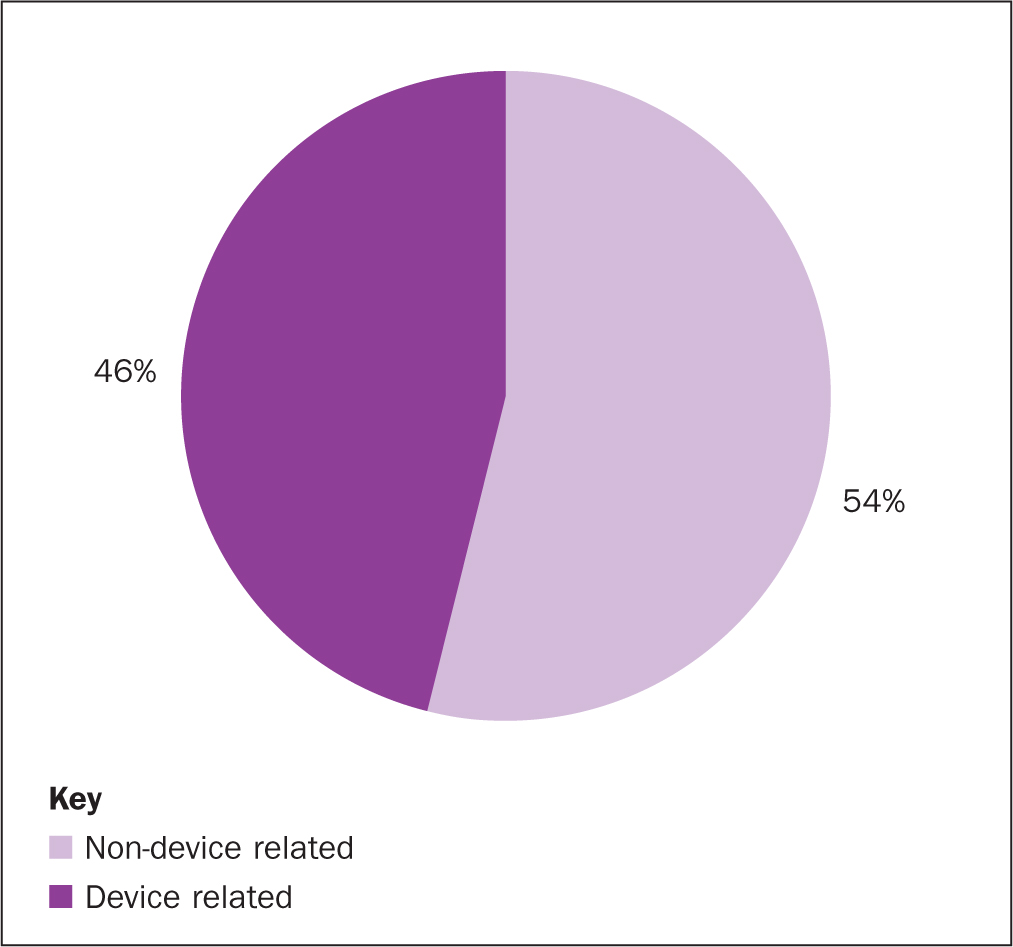

Within the 108 HAPUs at the Royal Marsden, none of the moderate-harm HAPUs were device related. Of the 105 low-harm HAPUs, almost half (46%) were caused by a device (Figure 2). The most prevalent devices that caused HAPUs were respiratory support devices (n=15), anti-embolism stockings (n=9) and nasogastric tubes (n=4)(Table 3). In three cases the impact of a device was not fully elucidated.

Table 3. HAPUs by device

| Label | Count |

|---|---|

| Respiratory support: | 15 |

| Oxygen nasal cannula | 4 |

| Oxygen mask/non-invasive ventilation/nasal high flow | 3 |

| Oxygen strap | 2 |

| Endotracheal tube/tie | 4 |

| Endotracheal tube anchor device | 2 |

| Anti-embolism stockings | 9 |

| Nasogastric tube | 4 |

| Arm of the chair | 2 |

| Central line/central venous catheter | 2 |

| Continence pad | 2 |

| Rectal drain | 2 |

| Anti-slip socks | 1 |

| Bandage | 1 |

| Blood pressure cuff | 1 |

| Chair recliner remote control | 1 |

| Deflated dynamic cushion | 1 |

| Glasses | 1 |

| Hearing aids | 1 |

| Nephrostomy tube | 1 |

| Rectal catheter | 1 |

| RIG (radiologically inserted gastrostomy) tube | 1 |

| Urinary catheter | 1 |

| ? Line | 1 |

| ? Possibly slide board | 1 |

| ? Theatre trolley | 1 |

| Total | 50 |

The recent findings from the GAPS study (Shalhoub et al, 2020) suggested that the routine use of anti-embolism stockings might be unnecessary for elective surgery patients. This may reduce stocking-related HAPUs locally and nationally if widely embraced as a policy.

Standards framework breakdown

A core curriculum for PU staff education was launched across NHS England in 2018 (NHS Improvement, 2018c), building on the original ‘SSKIN’ acronym used as a guide for PU prevention, and expanded to ‘ASSKING’ (assess risk, skin inspection, surface, keep moving, incontinence/increased moisture, nutrition, giving information).

The ASSKING acronym was used at the Royal Marsden as a framework to create internal pressure ulcer prevention standards. The Trust's PU standards either fulfil or exceed national and international best practice and were built into the mini-RCA investigation tool for low-harm HAPUs (Table 4). Having such PU standards allow ward leaders to easily recognise and understand their own local areas for improvement.

Table 4. Royal Marsden pressure ulcer standards within the mini root cause analysis tool

| ASSKING | Action: need to be able to evidence | Yes/No |

|---|---|---|

| Assess risk | Waterlow risk assessment completed within 4 hours of admission to the ward? Was it accurate? | |

| Waterlow risk assessment completed daily thereafter? | ||

| Surface | Pressure redistributing mattress/cushion in use, without delay and appropriate for patient condition? | |

| Skin inspection | Top-to-toe skin inspection completed and documented once per shift? | |

| Keep moving | Repositioning regimen prescribed, appropriate and documented fully and accurately? | |

| Was a manual handling care plan initiated within 12 hours of admission? Updated weekly thereafter? | ||

| Appropriate manual handling equipment in use? | ||

| Incontinence and moisture | Continence assessed and appropriate plan of care in place? | |

| Nutrition and hydration | Was the nutrition risk assessment completed within 24 hours of admission? Was it accurate? Completed weekly thereafter? | |

| Appropriate actions taken regarding nutritional intake? | ||

| Was a dietetic referral made when the PU was identified? | ||

| Giving information | Verbal education and/or patient information leaflet given and explained? Evidence of this? |

Considering each of the standards in turn allows, for the most part, the undertaking of a deep-dive thematic analysis relating to the 71 low-harm HAPUs that had a mini-RCA investigation completed in 2019-2020.

Skin inspection

As per Trust PU standards, a top-to-toe skin inspection is indicated once per staff shift. This can vary between two and three times in one 24-hour period depending on whether core nursing shifts or 12-hour shifts are in operation in the clinical area.

Within the 71 mini-RCAs for low-harm HAPUs this standard was achieved for 46 patients (65%), missed for 19 patients (27%) and deemed not applicable for 6 patients (8%). Of the 6 patients where this standard was not applicable, 2 consistently declined skin inspection and the parent of 1 paediatric patient declined skin inspection. It must be accepted that such frequent skin inspections are not always appropriate in some circumstances such as in end-of-life care where this intervention may cause significant distress or exacerbation of other symptoms.

Surface

This standard relates to whether pressure-redistributing equipment such as a mattress or cushion was in use, without delay and appropriate for the patient's condition. The mini-RCAs found that 60 patients (85%) had appropriate pressure-redistributing equipment in place, 6 (8%) did not and in 5 (7%) it was not applicable. For one of the patients who did not have appropriate equipment, a deflated faulty dynamic cushion was the root cause of the HAPU. Of the 5 patients for whom this standard was deemed not applicable, 3 patients declined the recommended equipment and 2 were in operating theatres, which are departments that do not use the same equipment standards as ward inpatient areas.

Keep moving

There are three ‘keep moving’ standards.

Repositioning regimen prescribed, appropriate and documented fully and accurately

This standard was achieved for 54 patients (76%), was not achieved for 13 (18%) and was not applicable for 4 (6%); of the ‘not applicable’ patients, two declined both the recommended equipment and also skin inspections.

Was a manual handling care plan initiated within 12 hours of admission? Updated weekly thereafter?

This standard was achieved for 63 patients (89%), not achieved for 5 patients (7%) and not applicable for 3 patients (4%). For the 3 patients for whom this standard was deemed not applicable, 1 was a paediatric patient who was repositioned by parents and so did not require a manual handling care plan at the time and 2 were in the operating theatres.

Appropriate manual handling equipment in use?

This standard was achieved in 68 patients (96%) and deemed not applicable for 3 patients (4%). Of these 3 patients, the paediatric patient, as discussed, did not require such equipment. One of the patients who developed an HAPU in the operating theatre was thought to have developed this as a result of manual handling or use of a slide board.

Incontinence/increased moisture

The mini-RCAs showed that 67 (94%) of the 71 patients had their continence assessed and had an appropriate plan of care in place, 2 patients (3%) did not and for 2 (3%), this was not applicable. Furthermore, of the 50 HAPUs caused by medical devices, it was interesting to note that 7 devices were related to managing incontinence: 1 rectal catheter system, 2 rectal drains, 2 continence pads, 1 nephrostomy tube and 1 urinary catheter.

Nutrition

The European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel et al (2019) guideline sets out nutritional screening and person-centred nutrition/hydration care planning expectations.

There are three PU standards for nutrition at the Trust.

Was the nutrition risk assessment completed within 24 hours of admission? Was it accurate? Completed weekly thereafter?

Of the 71, 64 patients (90%) received care achieving this standard, 5 (7%) did not and 2 (3%) were noted as N/A as they were in theatre.

Appropriate actions taken regarding nutritional intake?

Of the 71 patients, 65 (91%) had appropriate actions taken regarding nutritional intake, 4 (6%) did not have this optimised and 2 (3%) were noted as N/A as they were in theatre.

Was a dietetic referral made when the PU was identified?

Of the 71 patients, 35 (49%) were referred to the dietetic team when a PU was identified, 32 patients (45%) were not and for 4 patients (6%) a referral was inappropriate at the time. Of these 4 patients, two were in theatre, one was already known to the dietetic team and was nil by mouth (NBM) at the time of the HAPU and the fourth patient died on the day the HAPU developed.

Assessing risk

There are many risk assessment tools available for PUs. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) states that a risk assessment must be completed within 6 hours of admission using a validated risk assessment tool. Other than reassessing risk when a patients' condition changes, there are no guidelines to stipulate the reassessment frequency in any healthcare setting. Due to the lack of guidelines, healthcare organisations often set this target locally.

The two Royal Marsden PU standards for assessing risk state that the validated Waterlow risk assessment tool must be completed within 4 hours of admission/ward transfer and be completed daily as it is recognised that a patient's condition can change from day to day during an inpatient admission.

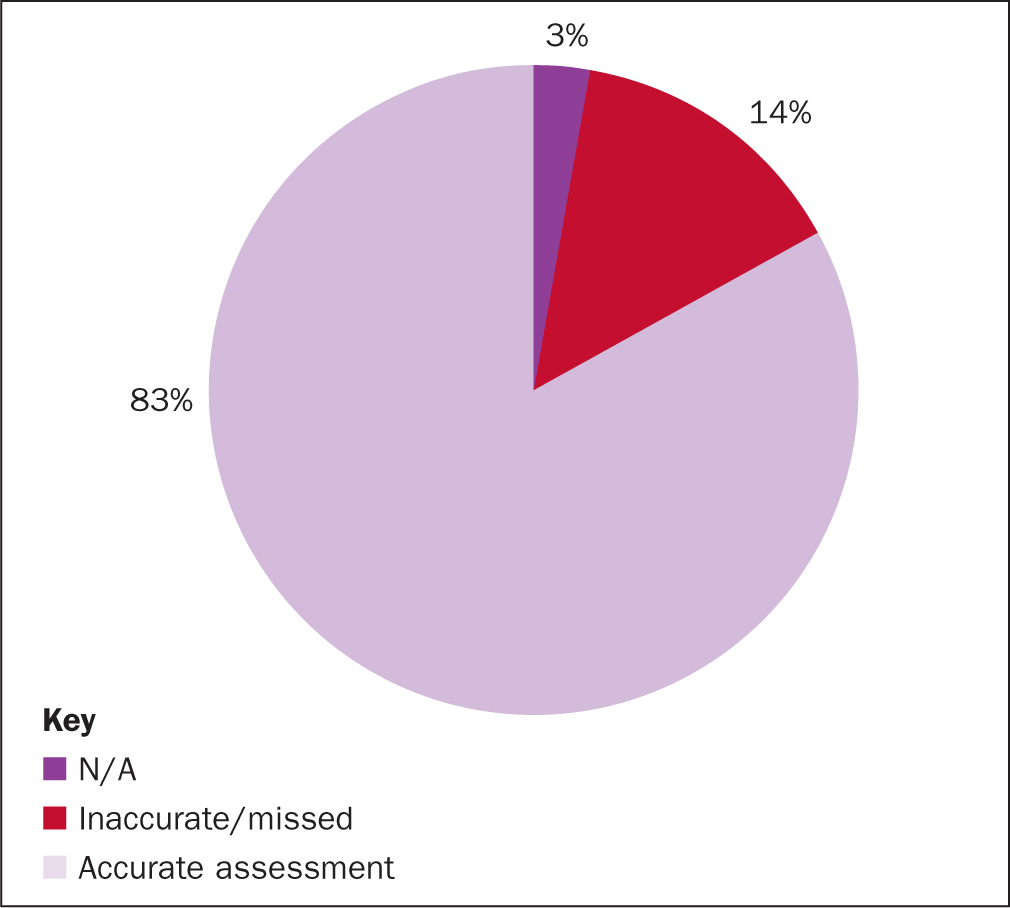

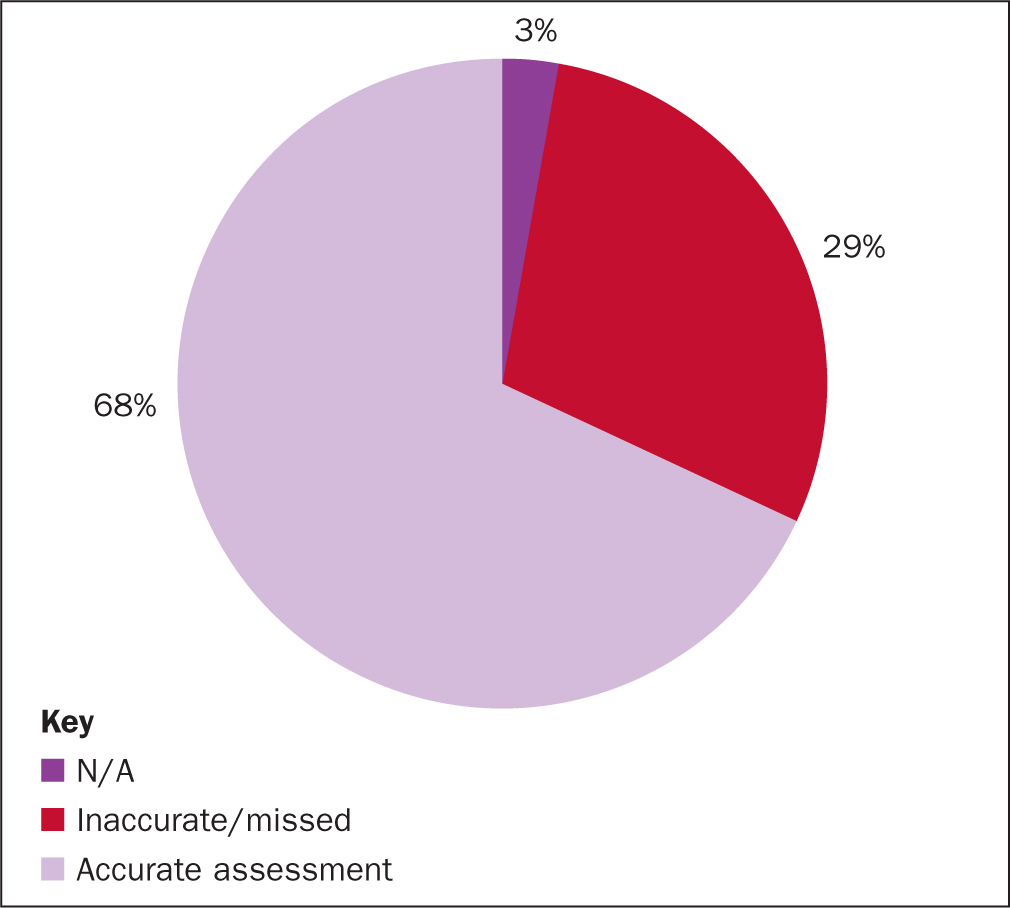

From the 71 mini-RCAs it was found that 83% of patients had an accurate Waterlow risk assessment completed within 4 hours of admission, 14% either missed the 4-hour target or the assessment was not accurate (Figure 3). The RCA also found that 3% believed that standard did not apply (ie 2 patients in theatre). Reassessment of risk was completed daily for 68% of patients and, as above, 3% did not apply (Figure 4).

Giving information

To achieve this Marsden PU standard there must be written evidence of either verbal PU prevention education provided or the patient PU information leaflet needs to be provided. This standard was achieved for 46 patients (66%), not achieved for 18 (25%) and N/A for 6 patients (8%). All of the 6 N/A cases were sedated, 4 in the critical care unit and 2 in theatre. Furthermore, of the 18 patients for whom this standard was not achieved, 7 were in critical care so the appropriateness/ability to fulfil this may have been compromised.

Discussion

As the observations from a skin inspection are required to fully and accurately complete a Waterlow PU risk assessment, the two factors therefore become intertwined. Of the 71 low-harm HAPU mini-RCAs, risk assessment was completed within the 4-hour target for 83% of patients, which is a credible achievement. Yet, the daily sustainability of this reduces to 68%. The Royal Marsden may wish to consider whether another validated risk assessment tool would offer a higher reassessment rate.

The skin inspection once per shift standard was missed for 19 patients (27%), which may be the reason for not obtaining such high risk assessment completion after admission.

Of the 71 patients, 94% had their continence assessed and deemed to have an appropriate plan of care in place to manage this. Despite this, almost half (49%) had continence/increased moisture listed as a contributory factor for their HAPU development. The inability to differentiate between incontinence or increased moisture as the contributory factor of these HAPUs brings significant restraints to where to focus quality improvement efforts.

Reviewing the effectiveness of the Royal Marsden continence care plan, optimising continence promotion activities and reviewing continence specialist nurse service provision would serve as a sufficient starting point for future improvement. However, increased moisture on the skin caused by excessive perspiration or skin folds from obesity may have limited interventional capability.

In this study, 90% of patients had the relevant nutrition risk assessments completed within the standard parameters and 91% were considered to have had appropriate actions taken regarding their nutritional intake. Despite the high level of achievement in the first two nutrition PU standards, 45% of patients were not referred to the dietitian when the HAPUs developed. Within the Royal Marsden PU prevention policy, all patients with a PU (HAPUs and present on admission) must be referred, including category 1 PUs. This should be investigated further and systems updated to rectify this disconnect to enable this standard to be achieved. Also, it may be necessary to explore the understanding of the term ‘appropriate actions’ for nutrition taken by ward staff.

In regard to the giving information standard, this was not achieved for 25% of patients and will be a key improvement activity going forward.

DRPUs: a key point to consider

Almost half (46%) of the Royal Marsden annual HAPU incidence were related to devices. Also of note is that none of the moderate-harm HAPUs were device related. The reasons for this is likely to be the differing physiology of PU development. PUs are a hypoxic event resulting in skin and tissue death. The hypoxia is caused by pressure occluding the blood vessels that deliver oxygen and nutrient-rich blood to the tissues.

In the case of a DRPU, it could be argued the external pressure loading exerted on the superficial tissue layers is less than the person's own body weight and therefore the damage would radiate through the tissue layers more superficially. However, the development of a ‘traditional’ non-device-related PU is due to the person's own body weight occluding the vessels via gravity and is a significantly higher level of pressure loading, which originates from the deeper layers. Occluding larger blood vessels, which supply larger surface areas in the subcutaneous and skeletal areas, will result in a deeper PU.

For this reason it could be hypothesised that, due to the physiological development of a DRPU, it would be less likely to cause a moderate-harm PU or death than a traditional PU. This can be evidenced in this 1-year thematic analysis and requires further research. Nevertheless, it should not deter the vigorous prevention activities for DRPUs, as significant harm could develop due to the psychological and emotional impact.

Excluding devices that cannot be repositioned or offloaded, the author suggests that reducing device-related HAPUs incidence may be more straightforward than for traditional HAPUs due to the earlier visual presentation of skin damage and the limited depth of hypoxic injury—this, of course, relies on high adherence to full skin inspections by staff and patients and the awareness and skill to implement preventive actions.

Next steps to reducing HAPUs

The findings from the analysis suggested that the following actions should be adopted by the Trust to reduce the future incidence of HAPUs. In the short term:

- Improve on skin inspection standard

- Create an early warning/referral trigger within incident reporting system to alert dietetic team of HAPUs

- Update incident reporting system to allow reporter to differentiate between incontinence-related skin damage and non-incontinence related skin damage

- Review the effectiveness of continence care plan and continence service provision to improve continence optimisation

- Redesign, test and implement Trust PU standards and associated mini-RCA tool for the operating theatres environment.

In the medium term, it is suggested that the Trust PU multidisciplinary working group be extended to include procurement staff and external personnel such as device manufacturers. Current clinical practice should be observed and measured in the context of best practice. This observation should include method of device insertion and fixation, device repositioning ability and associated documentation, device offloading and scoping of device alternatives.

Conclusion

The thematic analysis of 71 low-harm HAPUs mini-RCA investigations has uncovered further key lines of enquiry and identified aspects for future improvement in order to reduce HAPU incidence and improve patient outcomes. Following great successes in reducing HAPUs in previous years, the key focus for the Trust to continue this trend is reducing DRPUs, particularly in relation to airway management and anti-embolism stockings.

KEY POINTS

- Traditional hospital-acquired pressure ulcers (PUs) and device-related pressure ulcers have physiological differences in how they develop

- Device-related pressure ulcers are more likely to cause low rather than moderate patient harm

- Given adequate/appropriate data and use of thematic analysis methodology, clinicians can be enabled to plan locally relevant quality improvement interventions

- Specialist clinical areas such as theatres require different PU standards from ward areas to enable more effective root cause analysis investigations

CPD reflective questions

- Which devices are causing pressure ulcers in your clinical area?

- What data do you need to plan the next steps in your pressure ulcer prevention strategy?

- How is learning from hospital-acquired pressure ulcer incidents used to inform practice in your trust?