Peristomal skin complications (PSCs) are the most common postoperative complication following creation of an ostomy and remain a constant challenge for the majority of individuals with an ostomy. The incidence of PSCs is widely reported in the literature (Herlufsen et al, 2006; Richbourg et al, 2007; Gray et al, 2013; Salvadalena, 2013) and with great variability. Although a PSC rate of 18-60% has been summarised based on several investigations (Meisner et al, 2012), nurse specialists reported that nearly 80% of their patients developed PSCs (Colwell et al, 2017). These discrepancies in incidence reporting may reflect a non-systematic way of assessing PSCs among different health professionals (Martins et al, 2012). Importantly, the incidence of PSCs may be underreported by persons with ostomies partially due to them accepting that some degree of challenges associated with their ostomy are the ‘new normal’ and therefore they tend not to seek help and/or advice from a health professional.

PSCs can arise from a multitude of factors including trauma and mechanical injury due to adhesive stripping from repeated barrier application and removal. However, PSCs are primarily caused by leakage of ostomy effluents under the adhesive barrier resulting in an irritant contact dermatitis (Martins et al, 2011; Gray et al, 2013). Erythema or broken/sore skin are visual signs of PSCs, yet non-visual signs such as pain, itching, or burning sensations are equally important to address. Regardless of the cause, signs and symptoms of PSCs can have a tremendous negative impact on health-related quality of life for the patient and increased healthcare costs for society (Persson et al, 2005; Grant et al, 2011; Gray et al, 2013; Pittman et al, 2014). Consequently, it is important to minimise the risk of and detect PSCs at an early stage to prevent complications from worsening (Meisner et al, 2012). To do so, it is essential to continually improve the understanding of these complications and provide sensitive assessment tools for standardised detection.

The Ostomy Life Study is a recurrent multinational survey with the aim of capturing current life situations and challenges experienced by people living with an ostomy (Claessens et al, 2015; Fellows et al, 2017; Voegeli et al, 2020). In 2019, a new survey was conducted where one focus was to obtain a better understanding of the prevalence of PSCs, including both visual and non-visual complications. Moreover, the survey sought to explore actions taken by people living with an ostomy due to PSCs and understand how these skin complications physically and emotionally affected patients' daily life. Alongside this survey, a multinational survey for stoma care nurses was conducted. Among other aspects, this survey aimed to understand the high incidence of PSCs, causative factors, and suggested management for these skin problems. Collectively, this article aims to provide insight and improved understanding of the current prevalence of PSCs and subsequent effect on the daily life of people living with an ostomy.

Methods

Survey population

Survey for people with an ostomy

The first survey comprised questions relevant to the community of people living with an ostomy. Inclusion criteria included that subjects had to have at least one type of enterostomal ostomy and be more than 18 years of age. No further limitations were set for inclusion to ensure a broad and representative survey population. The survey was distributed to more than 54 000 people with an ostomy from 17 countries including the USA, China, Japan, UK, Germany, France, Brazil, Italy, Canada, Australia, Poland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium, Norway, and Denmark. Before answering the survey, participants consented to their participation and allowed Coloplast to use the collected aggregated anonymous data for internal and publication purposes. An online survey was sent via email through Coloplast country databases, the Coloplast Online Research Engine (CORE) survey panel (representing UK, USA, France, Germany, and Denmark), or in China via WeChat. The questions within the survey were translated into the local language.

Nurse survey

The companion survey targeted nurses working within ostomy care and was conducted both offline and online. A paper questionnaire was handed out to participants at the European Council of Enterostomal Therapists (ECET) congress in Rome in June 2019. An online survey was sent out by email to the CORE survey panel in November 2019 (representative languages: English, German, French, Spanish, and Italian). Finally, paper questionnaires were handed out at Coloplast Ostomy Forum (COF) meetings (representing Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Germany, UK, Canada, and France) in December 2019. A total of 328 nurses completed the survey with 168 respondents coming from the ECET conference, 72 from the CORE panel, and 88 from the COF session.

Survey design

Survey for people with an ostomy

The survey was estimated to take 30 minutes to complete and included demographic questions as well as questions related to living with an ostomy. The participants were asked to perform a self-assessment of their peristomal skin condition by recalling the last time they changed their ostomy barrier. They were asked to rate their level of pain, itching, and burning in the peristomal area on a scale of 0-10, where 0 indicated ‘no pain, itching, or burning’ and 10 indicated ‘worst possible level of pain, itching, or burning’. In addition, they were asked to answer if they had any weeping, bleeding, or ulcer/sore on the peristomal skin.

Following this, the participants were asked to recall the past 7 days and answer questions related to how PSCs or worry about PSCs affected their emotions and daily activities. These questions were answered on a five-point Likert scale (‘all the time’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘rarely’, ‘never’). Finally, they were asked how PSCs affected their ability to attend their job. This was only asked of the subpopulation who had indicated they were employed at the time of the questionnaire and was rated on a scale from 0-10, where 0 resembled ‘it had no effect on my work’ and 10 ‘it completely prevented me from working’. The numbers between 1 and 9 were afterwards translated into three categories with 1-3 considered as having low effect on ability to work, 4-6 moderate effect on ability to work, and 7-9 high effect on ability to work. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Nurse survey

The survey included questions related to experiences with PSCs and participants were asked to rank the three main reasons why patients develop PSCs from 15 pre-defined options. The recommended management of mild, moderate, and severe complications due to irritant contact dermatitis were captured as well as estimated time spent, and number of consultations required before different severity levels of PSCs were resolved. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data collection, processing, and analysis

Survey for people with an ostomy

Data gathering took place from August to December 2019. The online survey encompassed filters ensuring that each question was shown to relevant respondents only. Consequently, the number of respondents for each question varied. Participants with incomplete responses were excluded from the analysis. For the analysis part, only descriptive statistics were applied. To show sample characteristics, percentages of the total population were used for categorical variables.

Nurse survey

Data were collected using a combination of paper questionnaire and online survey. Before interpreting the results, the ‘don't know’/’blank’ answers were removed, so the number of people answering each question varies.

Results

Participating countries in the survey for people with an ostomy

The survey was sent out to more than 54 000 people living with an ostomy, and a total of 5187 people from 17 different countries completed the survey. The number of respondents across the participating countries is depicted in Figure 1a. In terms of percentagewise distribution of the respondents, the three main contributing countries were China (21%), the US (15%), and Japan (15%) (Figure 1b). The remaining participants were primarily from European countries and Australia with the exception of Brazil, which accounted for 1% of the respondents (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Participating countries in the survey for people with an ostomy. Number of participating people living with an ostomy listed across the 17 countries (a) and distribution of participants listed across the 17 countries (b). Percentages indicate share of the total participating ostomate population (n=5187)

Demographics of participating people with an ostomy

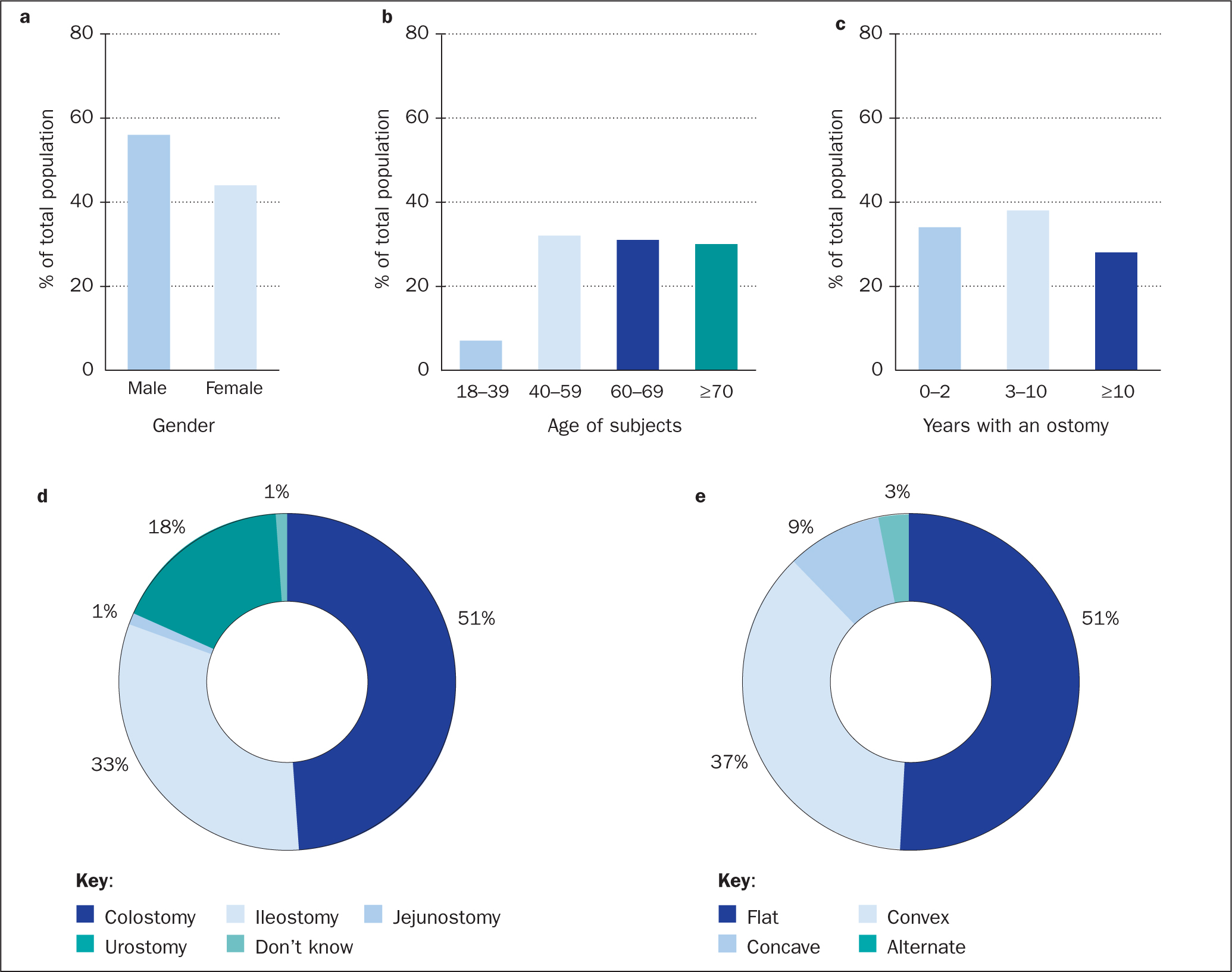

In the survey population, there was a slight overrepresentation of males at 56% of the respondents (Figure 2a). Although only 7% of the participants were 18-39 years old, there was an even distribution of respondents in the remaining age classes (Figure 2b). When evaluating the time since surgery, 34% had had their ostomy for 0-2 years, while 38% and 28% had had their ostomy for 3-10 years and more than 10 years, respectively (Figure 2c). There was an overrepresentation of people with a colostomy (51%) compared with participants with an ileostomy (33%) or an urostomy (18%) (Figure 2d). Although 1% had a jejunostomy, another 1% was unaware of their type of ostomy. A flat ostomy barrier was used by 51% of the population, 37% used a convex barrier, 9% a concave barrier, and 3% alternated between different types of barriers (Figure 2e).

Figure 2. Demographics of participating people with an ostomy: gender distribution (a); age (subjects were divided into four age classes) (b); years since surgery (subjects were divided into three categories based on ostomy age) (c); distribution of ostomy types (d); and type of ostomy barrier used by the participants (e). Percentages indicate percentage of total participating ostomy population (n=5187)

Figure 2. Demographics of participating people with an ostomy: gender distribution (a); age (subjects were divided into four age classes) (b); years since surgery (subjects were divided into three categories based on ostomy age) (c); distribution of ostomy types (d); and type of ostomy barrier used by the participants (e). Percentages indicate percentage of total participating ostomy population (n=5187)

Self-assessed visual and non-visual signs of PSCs

Self-assessment of the peristomal skin was completed by 4209 of the participants as the question was not directed at those who irrigated at the time of the survey (n=978). When asked to report the visual appearance of their peristomal skin, ostomates had to choose between four types of images (Figure 3a). From this, it was evident that almost half of the respondents (48%) considered their peristomal skin to have no visual signs of discolouration, while 32% and 16% reported mild and moderate discolouration, respectively (Figure 3b). Only 4% of the respondents considered their peristomal skin to have severe discolouration.

Figure 3. Self-assessed visual and non-visual signs of peristomal skin complications. Images show the answer options provided for visual appearance of peristomal skin. Four types of images were included indicating ‘no discolouration’, ‘mild discolouration’, ‘moderate discolouration’, and ‘severe discolouration’ (a). Based on these examples, ostomy participants reported the visual appearance of peristomal skin last time they changed their ostomy barrier (n=4209) (b). These were cross referenced with self-reports of other symptoms than discolouration (such as pain, itching, burning, weeping, bleeding, or ulcers) (c)—percentages are those of subjects within each of the four discolouration categories ‘no discolouration’, ‘mild discolouration’, ‘moderate discolouration’, and ‘severe discolouration’ experiencing at least one of the other symptoms. The final chart shows distribution of participants experiencing either no signs/symptoms or at least one sign/symptom of peristomal skin complications (as percentage of total (n=4209) (d)

Figure 3. Self-assessed visual and non-visual signs of peristomal skin complications. Images show the answer options provided for visual appearance of peristomal skin. Four types of images were included indicating ‘no discolouration’, ‘mild discolouration’, ‘moderate discolouration’, and ‘severe discolouration’ (a). Based on these examples, ostomy participants reported the visual appearance of peristomal skin last time they changed their ostomy barrier (n=4209) (b). These were cross referenced with self-reports of other symptoms than discolouration (such as pain, itching, burning, weeping, bleeding, or ulcers) (c)—percentages are those of subjects within each of the four discolouration categories ‘no discolouration’, ‘mild discolouration’, ‘moderate discolouration’, and ‘severe discolouration’ experiencing at least one of the other symptoms. The final chart shows distribution of participants experiencing either no signs/symptoms or at least one sign/symptom of peristomal skin complications (as percentage of total (n=4209) (d)

Although only half of the respondents indicated PSCs based on discolouration alone, the numbers were substantially higher when asking about other PSCs such as pain, itching, and burning as well as weeping, bleeding, and ulcerated/sore skin. Surprisingly, 75% of participants with no discolouration reported at least one of the other skin complications (Figure 3c): In addition to this, there was a trend towards the more discolouration, the higher the frequency of other complications as well. Collectively, these results revealed that a total of 3706 people reported discoloured skin and/or at least one of the other symptoms, which means that 88% of the participants had some level of PSCs (Figure 3d).

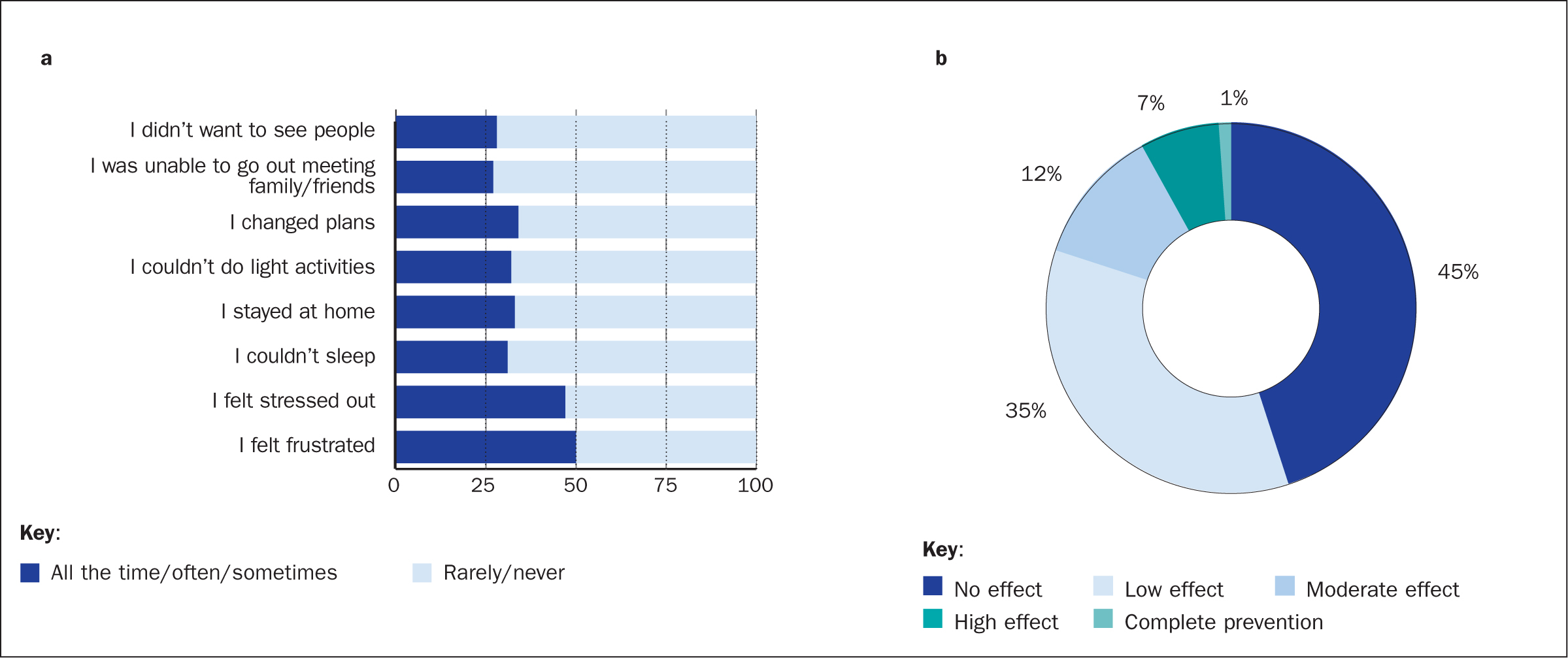

Self-assessed effect of having PSCs on daily activities

The ostomates were also asked how having a PSC or worrying about PSCs affected their emotions, daily activities, and ability to work. Half of the participants (50%) felt frustrated to some degree when experiencing PSCs, 47% felt stressed out, and for 31% it also affected their ability to sleep (Figure 4a). For approximately one-third, it affected their daily activities in the way that they stayed at home (33%), could not do light activities (32%), changed plans (34%), were unable to go out and meet family/friends (27%), or did not want to see people at all (28%) (Figure 4a). Twenty-five per cent of the participants in the survey were still full-time or part-time employed at the time of the survey, and this subset (n=1287) was asked how PSCs affected their work ability. Although 45% and 35% of this group reported no or low impact, respectively, 12% of the respondents answered that having a PSC had a moderate effect on their ability to work (Figure 4b). In addition, 7% reported a high impact on work ability and 1% said that having a PSC completely prevented them from working (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. Self-assessed impact of having peristomal skin complications. People living with an ostomy were asked how having a peristomal skin complication (PSC) or worrying about PSCs affected their emotions and daily activities (percentages are of total participating ostomy population, n=5187) (a) and ability to work (percentages are of the subpopulation who were still working, n=1287) (b)

Figure 4. Self-assessed impact of having peristomal skin complications. People living with an ostomy were asked how having a peristomal skin complication (PSC) or worrying about PSCs affected their emotions and daily activities (percentages are of total participating ostomy population, n=5187) (a) and ability to work (percentages are of the subpopulation who were still working, n=1287) (b)

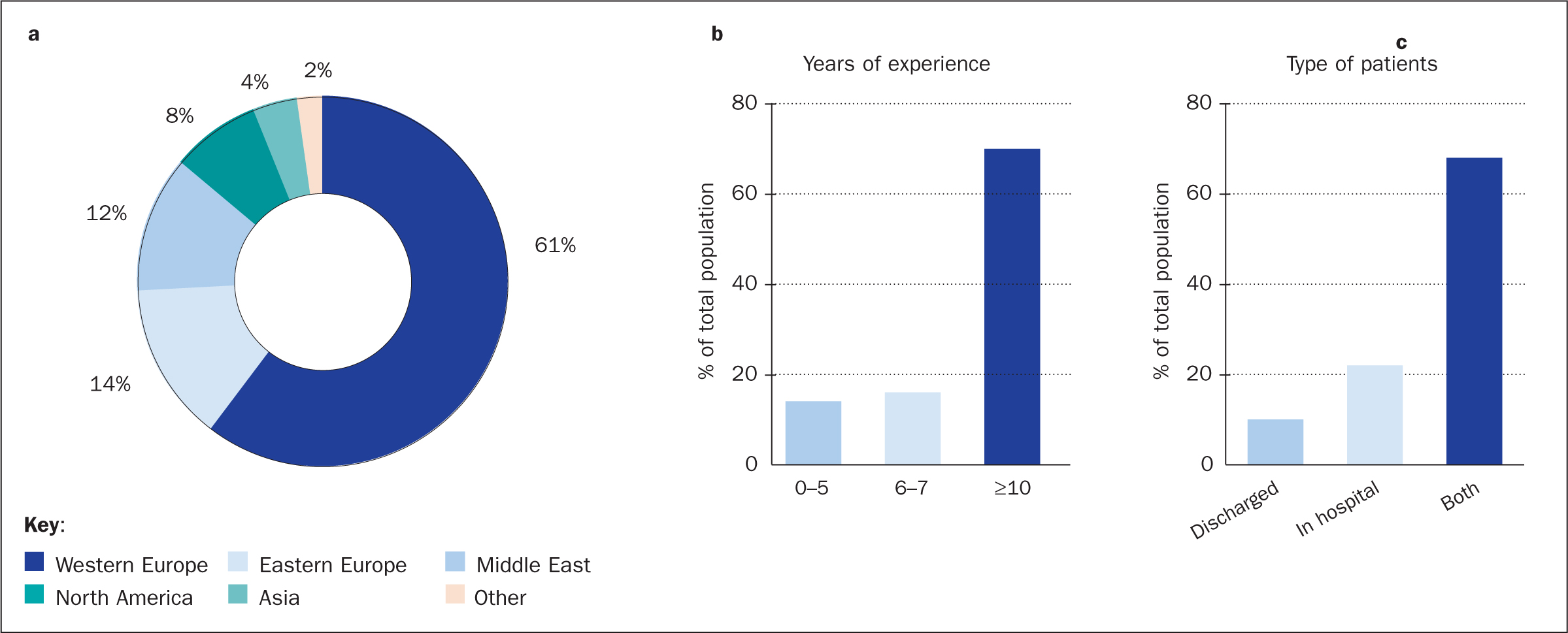

Demographics of participating nurses

For the nurse survey with 328 respondents, more than half of the nurses came from Western Europe (61%) with Eastern Europe and the Middle East being the two following main contributors with 14% and 12% of the respondents, respectively (Figure 5a). The remaining participants came from North America (8%), Asia (4%), or other areas (2%). Seventy per cent of the participating nurses had more than 10 years of experience (Figure 5b). The majority of the respondents (68%) saw both hospitalised and discharged patients, while 22% only saw patients in the hospital and 10% only saw discharged patients (Figure 5c).

Figure 5. Demographics of participants in the nurse survey: geographic distribution (a), years of experience within the field (b) and type of patients seen by the participating nurses (c). Percentages indicate percentage of total participating nurse population (n=328)

Figure 5. Demographics of participants in the nurse survey: geographic distribution (a), years of experience within the field (b) and type of patients seen by the participating nurses (c). Percentages indicate percentage of total participating nurse population (n=328)

Reasons for PSCs and how to handle them

Among the 328 answers received from the nurse survey, 80% believed that the main reason for developing PSCs was ostomy-related issues such as type of ostomy, retracted ostomy, or just a poorly located ostomy in general (Figure 6a). Leakage under the adhesive barrier was considered one of the main reasons for PSCs by 66% of the nurses and 60% considered the body profile including body mass index (BMI), creases, folds, and hernia in the peristomal area to be one of the main reasons for getting PSCs (Figure 6a). In addition, 49% considered incorrect product use a main contributor to developing PSCs, and 36% answered that the underlying disease played a major role.

Figure 6. Causative factors and recommended management of peristomal skin complications (PSCs). The nurses indicated their perception of the underlying reasons for developing PSCs—respondents could choose more than one option for their answer, percentages are of the total participating nurse population (a). irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) was considered the most prevalent type of PSC among the nurses, who indicated their recommended management based on severity (b). Nurses also indicated the number of nurse consultations/contacts usually required for resolving the PSC, based on severity (c)

Figure 6. Causative factors and recommended management of peristomal skin complications (PSCs). The nurses indicated their perception of the underlying reasons for developing PSCs—respondents could choose more than one option for their answer, percentages are of the total participating nurse population (a). irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) was considered the most prevalent type of PSC among the nurses, who indicated their recommended management based on severity (b). Nurses also indicated the number of nurse consultations/contacts usually required for resolving the PSC, based on severity (c)

The participating nurses regarded irritant contact dermatitis as a more prevalent type of PSC than mechanical trauma. Based on this, the nurses were asked to reflect on the actions taken to prevent irritant contact dermatitis, and how to handle irritant contact dermatitis was dependent on the severity level of the complication. For mild complications, modifying the hole in the adhesive baseplate was considered to be important advice to help in avoiding irritant contact dermatitis by 63% of the nurses (Figure 6b). The use of accessories was regarded as equally important for treatment of mild (61%), moderate (66%), and severe (59%) skin complications, whereas the use of a topical steroid, referral to a dermatologist, surgeon or physician were aspects more likely to be necessary for more severe skin complications.

The number of consultations needed to solve PSCs differed depending on the severity level of the complication (Figure 6c). Specifically, although 1-2 consultations often were sufficient for mild cases, moderate PSCs cases often required 3-4 contacts with a nurse. For severe cases, more than five contacts were often necessary for solving the PSCs (Figure 6c). Collectively, these data suggest a correlation between the severity of the skin complication and the number of consultations with a nurse needed to resolve the condition.

Discussion

To date, this Ostomy Life Study 2019 is the largest global survey performed on this topic. The results presented here underline the high prevalence of PSCs and the associated challenges present within the broad population of people living with an ostomy. As the condition of the peristomal skin can change rapidly, it is extremely important to monitor the skin closely to avoid development or progression of an existing PSC. To do so, sensitive instruments are required that can capture even small changes over time in a systematic and standardised manner.

Although there are other assessment tools for evaluation of the peristomal skin condition (Haugen and Ratliff, 2013; Parnham et al, 2020), current state of the art is the validated clinical assessment instrument, the Ostomy Skin Tool (Martins et al, 2010; Jemec et al, 2011). This tool has been widely used in clinical studies; however, the instrument has a limitation, as it relies on visual signs of PSC, and in particular discolouration, being present (Jemec et al, 2011). Consequently, the scoring system will not capture sensation symptoms such as pain, itching, and burning in the absence of discoloured skin.

The data presented here revealed that 75% of the ostomates who did not report discolouration experienced one or more sensation symptoms (pain, itching, burning) or observable symptoms (weeping, bleeding, ulcers). Although not visible, and therefore extremely difficult for health professionals to detect, symptoms such as pain, itching, and burning may heavily impair quality of life (QoL) for patients. In a cross-sectional study comparing 73 patients with chronic pruritus (characterised by severe itching) and 138 patients with chronic pain, it was shown that pruritus had a considerable effect on QoL, which might be in the same range as the impairment caused by pain (Kini et al, 2011). Likewise, assessment of QoL in patients with burning mouth syndrome demonstrated a significant reduction compared with healthy controls (López-Jornet et al, 2008). Based on the existing literature alongside the findings presented here in this study, it is evident that sensation symptoms such as pain, itching, and burning are crucial to take into consideration in future clinical practice. However, as the current tools do not capture sensation symptoms to the same extend, future development of improved assessment instruments will be of great importance to fully understand incidences and provide the correct treatment for patients with visual and non-visual PSCs.

PSCs may bring health-economic consequences for society. From the nurse survey, it was evident that there was a correlation between the required number of consultations with a nurse to solve the skin condition and the severity of the PSCs. Consequently, the burden for the health professionals and the associated healthcare costs increase when PSCs become more severe. In another nurse survey, only 38% of the patients coming to the clinics agreed with the nurse that they had PSCs (Herlufsen et al, 2006). Patients often failed to recognise that they had a skin disorder, and more than 80% of them did not reach out for health professional guidance (Herlufsen et al, 2006).

People living with an ostomy may often perceive PSCs as the ‘new normal’. However, it is important to treat or even prevent skin complications at an early stage both for the people living with an ostomy and from a health-economic point of view. The average costs of ostomy supplies has been reported to increase six-fold over a 7-week period for subjects with severe PSCs (Nichols and Inglese, 2018). Collectively, this underlines that the high prevalence of people living with PSCs comes with considerable economic costs for the society and proper handling is crucial. Moreover, the data presented here confirmed previous findings showing that leakage is a main contributor to developing PSCs (Herlufsen et al, 2006; Martins et al, 2011).

Despite useful findings, this study had some limitations. The data is based on questionnaires sent to a broad multinational population of ostomy care nurses and people living with an ostomy. Management of skin complications may depend on local guidelines and availability of ostomy care products, which is not reflected in this study. All skin assessments in the survey for people with an ostomy were self-reported and not confirmed by health professionals. However, given the large number of respondents, it still provides a valuable insight into the prevalence and impact of PSCs.

Conclusions

The data revealed a high frequency of ostomates without peristomal discolouration who still experienced sensation symptoms (pain, itching, burning) and/or observable symptoms (weeping, bleeding, ulcers). In addition to the direct consequences of compromised skin and sensation symptoms, PSCs come with a financial cost and a reduced health-related QoL. The emotional burden and restrictions on daily activities caused by PSCs heavily impair the life of the person living with the skin condition, and the society will experience increased treatment costs as PSCs may develop and progress into more severe stages.

KEY POINTS

- Peristomal skin complications (PSCs) impair quality of life for most people living with an ostomy and bring substantial healthcare-related costs to society

- Pain, itching, and burning are non-visual signs of PSCs, which are extremely difficult for health professionals to capture and therefore underreported

- Increased understanding of PSC prevalence and associated challenges may improve the management and prevention of these skin complications

- Systematic and standardised incidence reporting may require future development of improved assessment instruments to capture the full spectrum of PSC symptoms

CPD reflective questions

- Reflect on how you can clearly distinguish between the non-visual symptoms of a peristomal skin complication (PSC), namely pain, itching, and burning

- How can improved understanding of the variety of PSC symptoms (visual and non-visual) impact your treatment practice?

- If a new assessment instrument capturing the full spectrum of PSC symptoms is introduced, how could you ensure that it becomes implemented?