Adverse events in hospitals resulting from unsafe care are likely to be one of the 10 leading causes of death and disability in the world (Jha, 2018). In high-income countries, it is estimated that one in every 10 patients is harmed while receiving hospital care (Slawomirski et al, 2017). Although several factors are responsible for patient harm, almost 50% of these are preventable (de Vries et al, 2008).

In low- and middle-income nations, almost 134 million adverse events happen in hospitals because of unsafe practices, resulting in 2.6 million deaths every year (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2018). Worldwide, four in 10 patients experience adverse effects in primary and outpatient settings; 80% of adverse events in these settings are preventable. The errors arise in diagnosis, and when prescribing and administering medication (Slawomirski et al, 2018).

In Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, adverse events are responsible for 15% of all hospitalisations, and 15% of hospital expenditure is on tests and interventions to treat the harm they cause (Slawomirski et al, 2017). Appropriate investment to reduce patient harm leads to substantial financial savings as well as improve patient outcomes (Slawomirski et al, 2017).

Intravenous (IV) therapy is provided to around 85% of hospitalised patients in the US (Mattox, 2017). Vascular access device complications include catheter-associated venous thrombosis, infiltration and extravasation, and infection (Mattox, 2017).

Thrombophlebitis and extravasation are the most common complications of peripheral venous cannulation (Mattox, 2017). This may progress to local or systemic infection in some patients (Tjon and Ansani, 2000). Healthcare-associated infections occur in seven and 10 out of 100 inpatients in high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries respectively (World Health Organization, 2011).

Between 20% and 80% of adverse drug events (ADEs) are preventable (Woo et al 2019). Medication errors incurred during prescribing and administration are key contributors to ADEs (Carayon et al, 2014). Medication administration errors (MAEs) account for a median of 19.1% of total opportunities for error in hospitals (Keers et al, 2013).

IV route administration is associated with the highest MAE rates and more serious consequences to the patient than any other route; in the UK, errors can be five times more likely when drugs are administered intravenously (Kuitunen et al, 2021). In addition, IV therapy is five times more likely to be associated with an MAE than non-IV administration (McLeod et al, 2013). Intravenous medication errors lead to patient harm far more than other errors (National Patient Safety Agency, 2007).

In the UK, preventable ADEs have been estimated to cost the NHS £98.5 million per annum, requiring an avoidable 181 626 bed-days (Hodkinson et al, 2020).

ADEs and preventable ADEs in the US have been said to incur increased adjusted costs of $3420 and $3511 and an adjusted increase in length of stay of 3.15 and 3.37 days respectively. ADE severity is associated with higher costs. The additional costs and length of stay have been reported as: $2852 and 2.77 days for significant ADEs; $3650 and 3.47 days for serious ADEs; and $8116 (5.54 days) for life-threatening ADEs; (all P<0.001) (Hug et al, 2012).

Background

Identification of harms and risks through patient assessment, care planning, active surveillance, monitoring and double-checking are some strategies for meeting organisational goals related to patient safety (Henneman, 2017). Besides organisational commitment, training for clinical staff and compliance to patient safety principles are needed to prevent lapses and achieve a reliable, safe healthcare system (International Council of Nurses, 2019).

Fundamentally, patient safety requires an error-proof environment where carefully designed systems, tasks and processes are established and can shield health professional from making mistakes (Leape, 1997). Various studies have demonstrated that higher levels of nursing education were associated with better outcomes (Audet et al, 2018).

A structured orientation and training programme may result in behavioural, attitudinal and organisational changes in clinical practices resulting in lower infection rates and fewer medication errors with IV therapy. The Preventing Risks of Infections and Medication Errors with IV Therapy (PRIME) programme was set up for implementation in multiple countries in Asia.

Methods

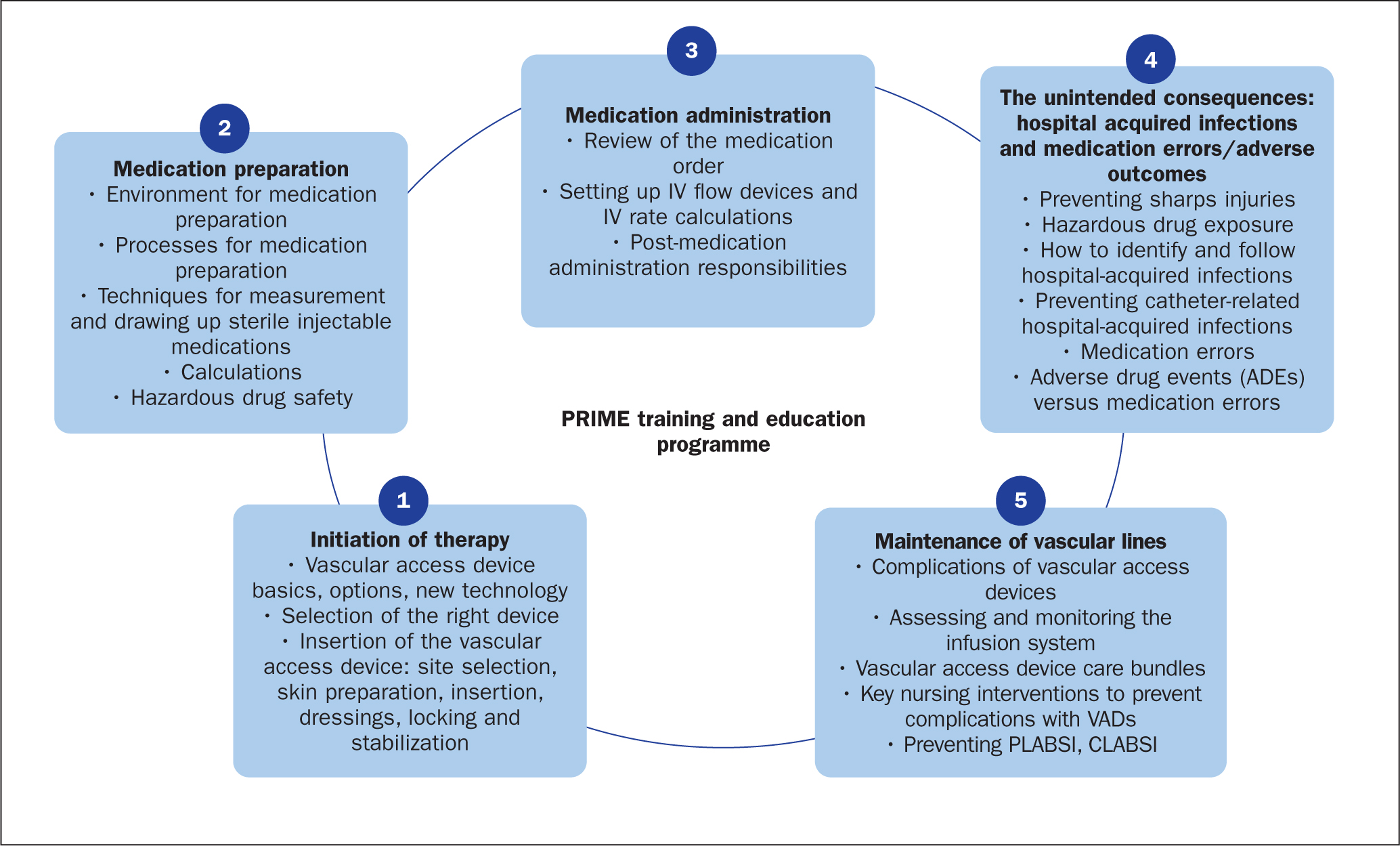

PRIME was designed to impart critical and fundamental skills around IV therapy initiation, medication preparation, medication administration and the maintenance of IV lines, incorporating best global practices. It comprised five sections: medication preparation; initiation of therapy; medication administration; maintenance of vascular lines; and surveillance of healthcare-acquired infections and incidence reporting. It was put together by a group of Joint Commission International (JCI) consultants; the programme also gave an overview of the JCI's patient-centred standards and healthcare organisation management standards. The training involved continuous interaction to facilitate the consistent adoption of learning approaches for all hospital stakeholders.

The programme goals were focused on two fundamental areas:

- Improving knowledge and skills on medication preparation and administration and VAD placement and maintenance; this was evaluated through interviews and observations by safety champions, who delivered the training to frontline staff

- Improvement in compliance to the PRIME programme standards, based on JCI medication error prevention and infection prevention standards, was evaluated through the feedback of programme leaders and the champions.

PRIME facilitators and course structure

The JCI's mission is to continuously improve the safety and quality of care in the international community through education, advisory services, and international accreditation and certification. JCI developed the course content (Figure 1) and delivery independently.

Introduction

Twenty-one tertiary hospitals in Indonesia, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam volunteered to implement the PRIME programme. The programme, which had a duration of 6 months, was run between May 2019 and March 2021. Each hospital decided its own start and end dates.

Safety champions from the hospitals—mainly nursing supervisors and nursing educators—to train the frontline staff were selected.

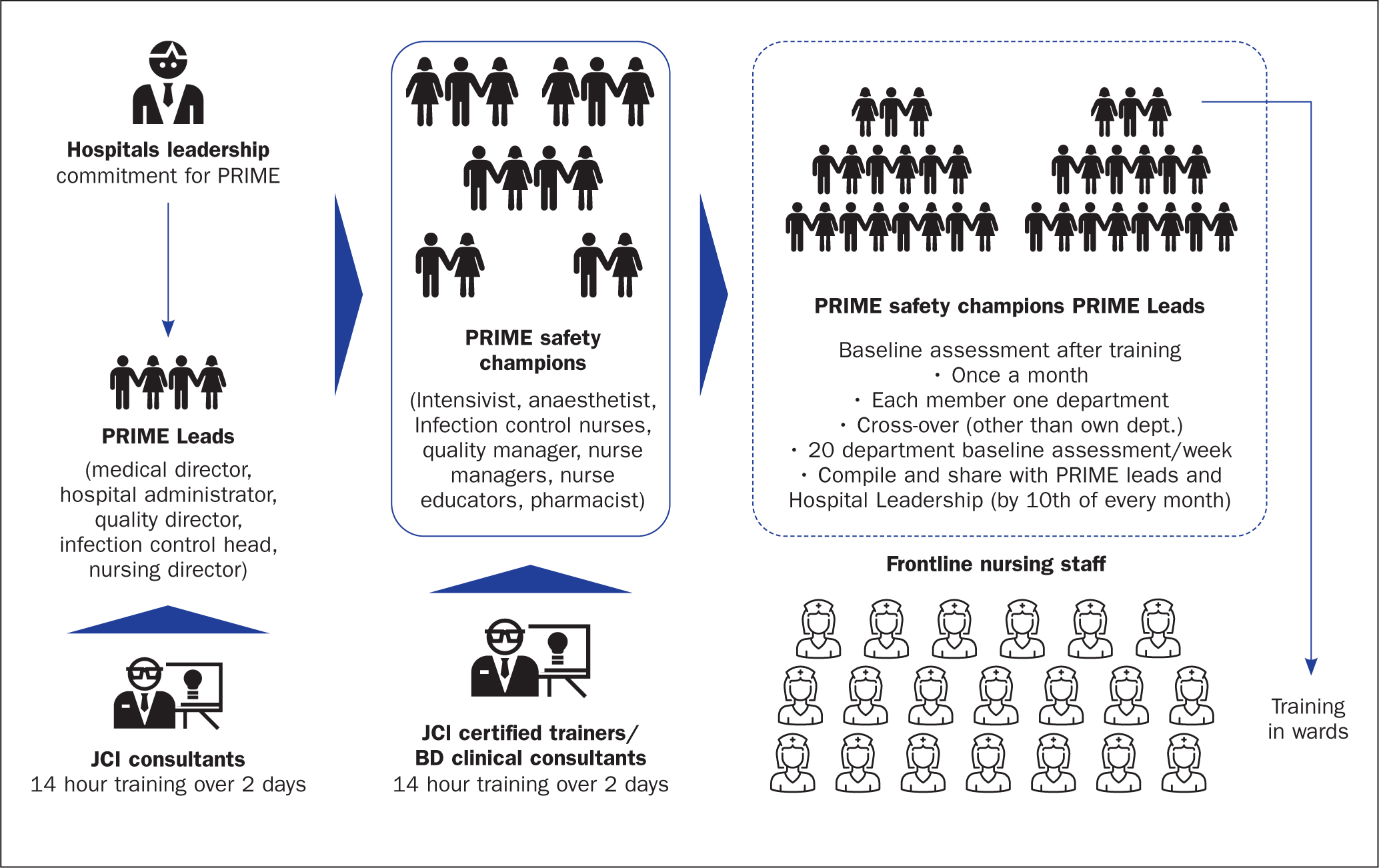

The first step was training the safety champions. The training sessions were facilitated by clinical consultants who worked for Becton Dickinson (BD), who had been trained by JCI consultants. BD, a medical technology company, sponsored the programme. The second step involved nursing leaders training frontline staff by nursing leaders with support from JCI-certified trainers (Figure 2).

The programme's leadership and implementation groups were divided into two groups, with clearly laid out roles and responsibilities:

- PRIME programme leads at the hospitals held roles including medical/nursing director, hospital administrator, quality director, infection control head, infection control officer, infection control nurse, quality nurse and nursing supervisor. There were a minimum of three and a maximum of five leads per hospital. Their responsibilities were to interact with JCI consultants and the BD clinical consultants and share programme updates with hospital leadership. They also analysed the audit data shared by safety champions and gained an understanding of the challenges, especially in areas of non-compliance, and made suggestions on corrective and preventive actions.

- PRIME safety champions, who made up the implementation team, included intensivists, anaesthetists, infection control nurses, quality managers, nursing leaders/managers, nurse educators and pharmacists. This ensured department leaders from all clinical areas across the hospital were represented. This group was trained by JCI-certified trainers (the BD clinical consultants). The duration of training was 14 hours spread over 2 days in the hospital premises. With representation from each clinical department, trainee groups had between 20 and 52 participants. Armed with knowledge and insights on best practices, the safety champions trained (1-2 hour duration) nurses during their shifts in specific wards. This had the following schedule:

- – Week 1: Safe medication preparation practices, including aseptic technique, calculations, the five rights (the right patient, the right drug, the right time, the right dose and the right route), hazardous medication and the health professional's safety

- – Week 2: Selection and initiation of vascular delivery of medications, including intramuscular and subcutaneous injection, and processes for placing VADs

- – Week 3: Medication administration

- – Week 4: Prevention of complications, peripheral or central line-associated bloodstream infections, adverse drug events, and medication error reporting.

After undergoing training, the safety champions had to demonstrate, communicate and, to some extent, ensure staff knew the hospital leadership was committed to PRIME. This team would also conduct monthly assessments in the form of interviews to assess knowledge and compliance to bedside practices as well as monthly observations in various clinical areas using an audit tool provided in the programme toolkit. The objective of these assessments was to identify areas of non-compliance and to address them individually. It was essential to compile, tabulate and report the observations with the programme leads every month (preferably by the 10th day of the month).

Monthly, online meetings between the hospital leaders and JCI consultants were scheduled a part of the programme. Here, the leaders could share the progress, ask questions and seek expert inputs on areas for improvement. These areas were identified based on the compliance scores at monthly audits.

Audit procedure

Evaluation of the impact and adherence to best practices is critical to measure the success of any initiative. An audit tool was created to evaluate the adoption of key skills taught within the programme. Audits were performed by individuals from other departments to overcome internal bias. They were performed for the following reasons:

- To identify areas of knowledge and skills where further training was needed

- To identify opportunities to improve performance and ensure greater adoption of best practice

- To measure proficiency in key skills as a metric of programme success, which was reported monthly to hospital leadership.

To maintain neutrality and independence, no JCI or BD clinical consultants were involved in the audit process. These audits were conducted monthly for 6 months at every hospital after nursing staff had been trained. The clinical areas audited were randomly chosen from wards involved in the programme.

Evaluation

Detailed evaluation and observation criteria of frontline nursing staff were drawn up. The investigation methodology, guidance on questioning and reference points were set out in detail in the evaluation sheet. The two broad-based areas were ‘medication preparation and administration’ and ‘placement and maintenance of VADs’. Under these major areas were sub-areas, which allowed holistic scrutiny of any behavioural change in nursing practices.

Data compilation

A total of 21 hospitals were enrolled in and completed the programme. Within these hospitals, more than 100 hospital leaders (around five per hospital) and over 400 programme leads and clinical champions (around 20 per hospital) were involved. Of the 21 hospitals, only 19 have their audit data included in this paper as two opted out of sharing their results.

Results

Data analysis was conducted by an independent agency commissioned and paid for by BD, the programme sponsor. Complete freedom was given to the agency so transparent and unbiased outcomes would be generated free from external influence. Hospitals were anonymised during the data analysis process. A unique code was assigned to each hospital datasheet.

The objective was to measure programme uptake, efficacy and outcomes in aggregate. First, individual hospital data were analysed, followed by compilation of all the data to arrive at an overall analysis. The outcome reporting paints a full picture after combining all 19 hospitals' data.

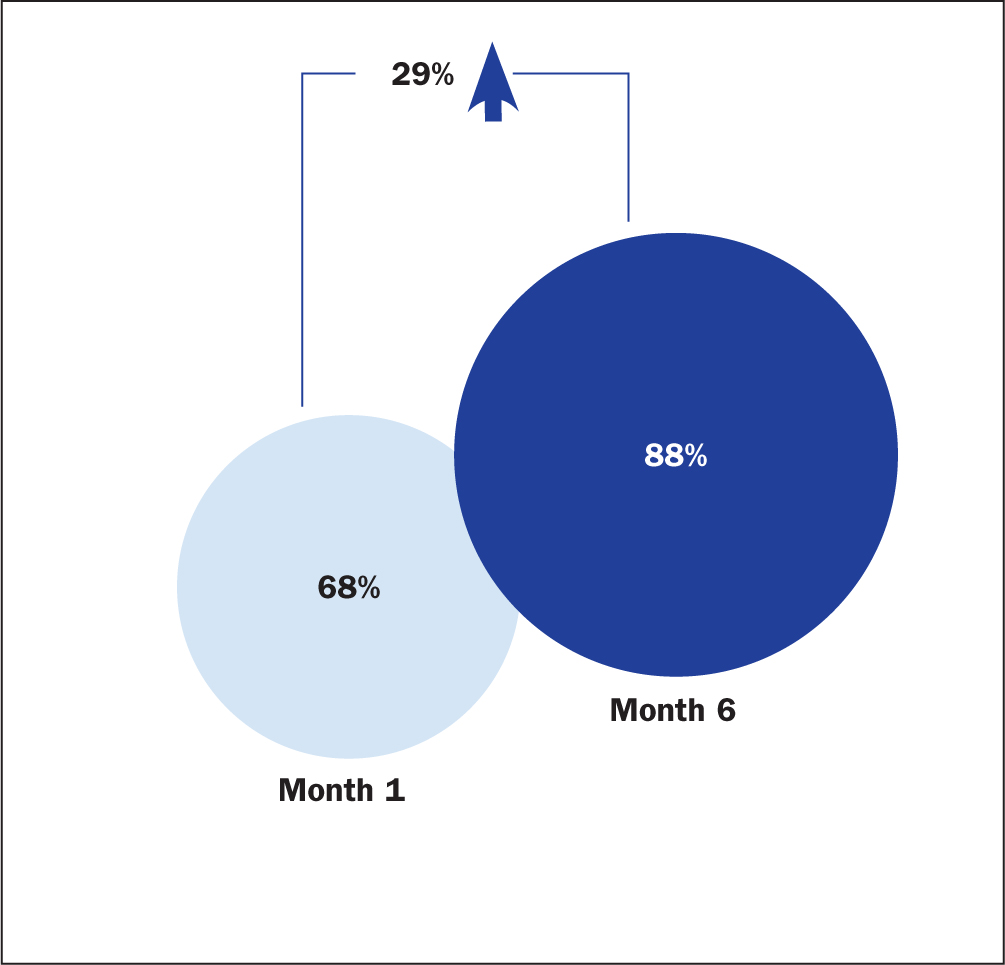

Figure 3 shows the improvement in process compliance on all parameters between the beginning and end of the process. There was a 29% aggregate increase in compliance with all parameters, although there was variation between individual hospitals.

Key skills taught about medication preparation and administration were evaluated using an audit tool, which covered many areas, including:

- Hand hygiene steps adherence

- Technique in removing medication from an ampoule and/or vial

- Medication preparation: this was observed in the area where this is carried out

- Dosage calculation: calculations made for drug quantity before administration were observed

- Drug incompatibility assessment: whether nurses understood whether it was safe to mix two or more drugs before administration

- Maintaining vascular lines using flushing and locking.

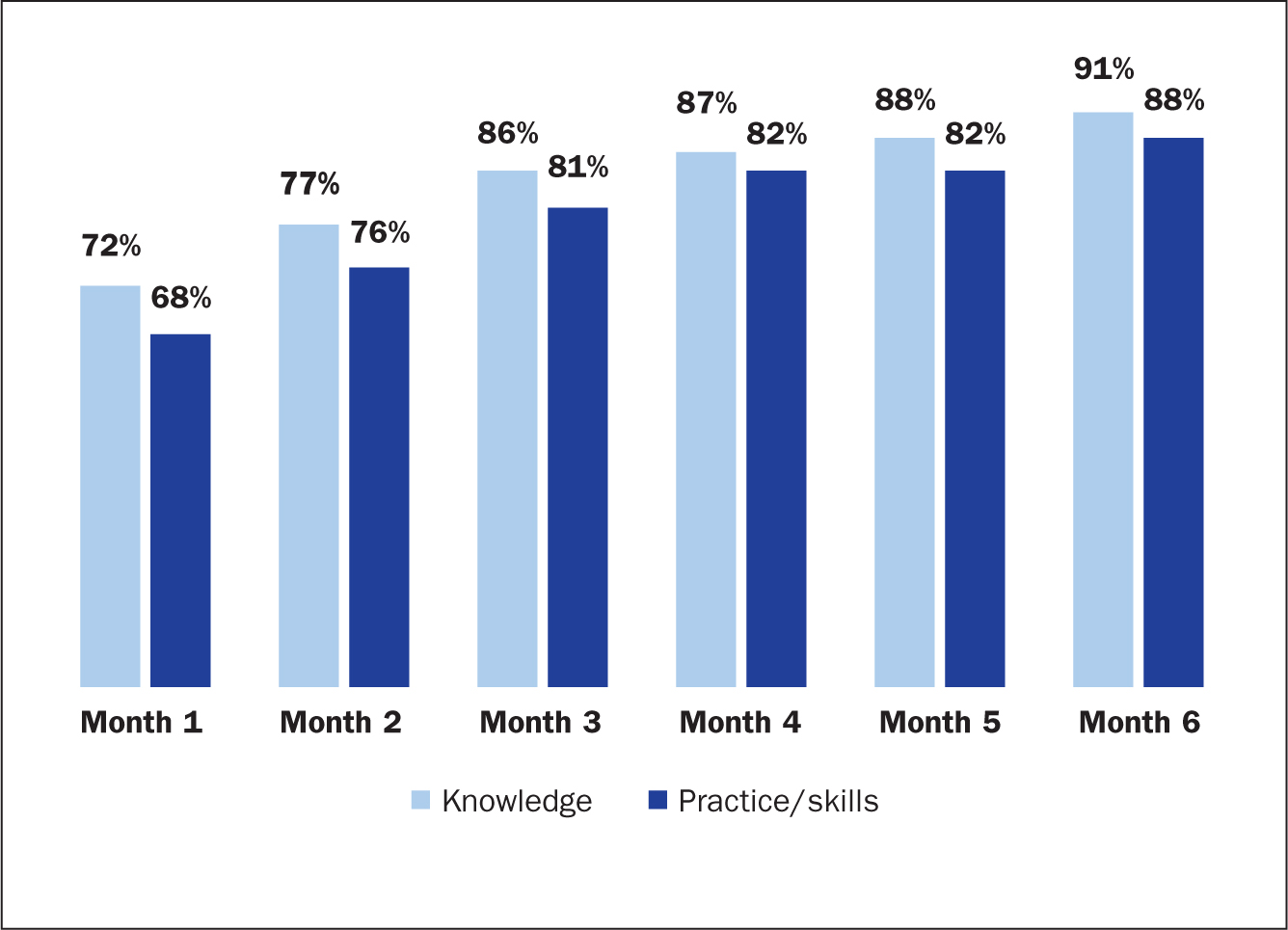

Knowledge levels showed steady gains consistently over a span of 6 months. The audit showed levels of compliance at 72% at month 1, rising to 91% at the end of 6 months. The impact of acquired knowledge through training and mentoring is reflected in enhanced skill levels. Skill levels at month 1 stood at 68% compliance, increased consistently to reach 88% at the end of the 6 months (Figure 4).

VAD placement and maintenance education training audit examined the following areas:

- Placing and maintaining VADs: the correct gauge of catheter, the correct location of insertion, the correct venous catheter based on the patient and site care

- Administration of subcutaneous insulin injections

- Administration of intramuscular injections

- Awareness of central and peripheral VAD placement

- Observation of four randomly chosen nurses in different wards in each hospital administering medications was analysed regarding use of sharps containers, observation, correct hand hygiene, five rights, giving the patient information about the medication being administered and other information they need, and correct calculation of drug amount or dose

- Interviews were carried out with another randomly chosen four nurses per hospital who administer medications on five rights, clarifying drug orders, concerns about prescriptions with the physician, practices to avoid medication errors, medication error reporting methodologies, steps to take when a patient has had an adverse drug reaction, identification of look-alike and sound-alike medicines, and awareness about high-alert medications

- Interviews were carried out with another four nurses in each hospital who have patients with VADs and their knowledge assessed about VAD complications, preventing these complications and VAD care bundles, plus their ability to discuss the five elements of central line-associated bloodstream infection (hand hygiene, maximum barrier precautions, skin antisepsis using chlorhexidine, selection of best catheter insertion site (avoiding femoral vein) and daily review of line necessity) and respond to device complication or suspected device infection.

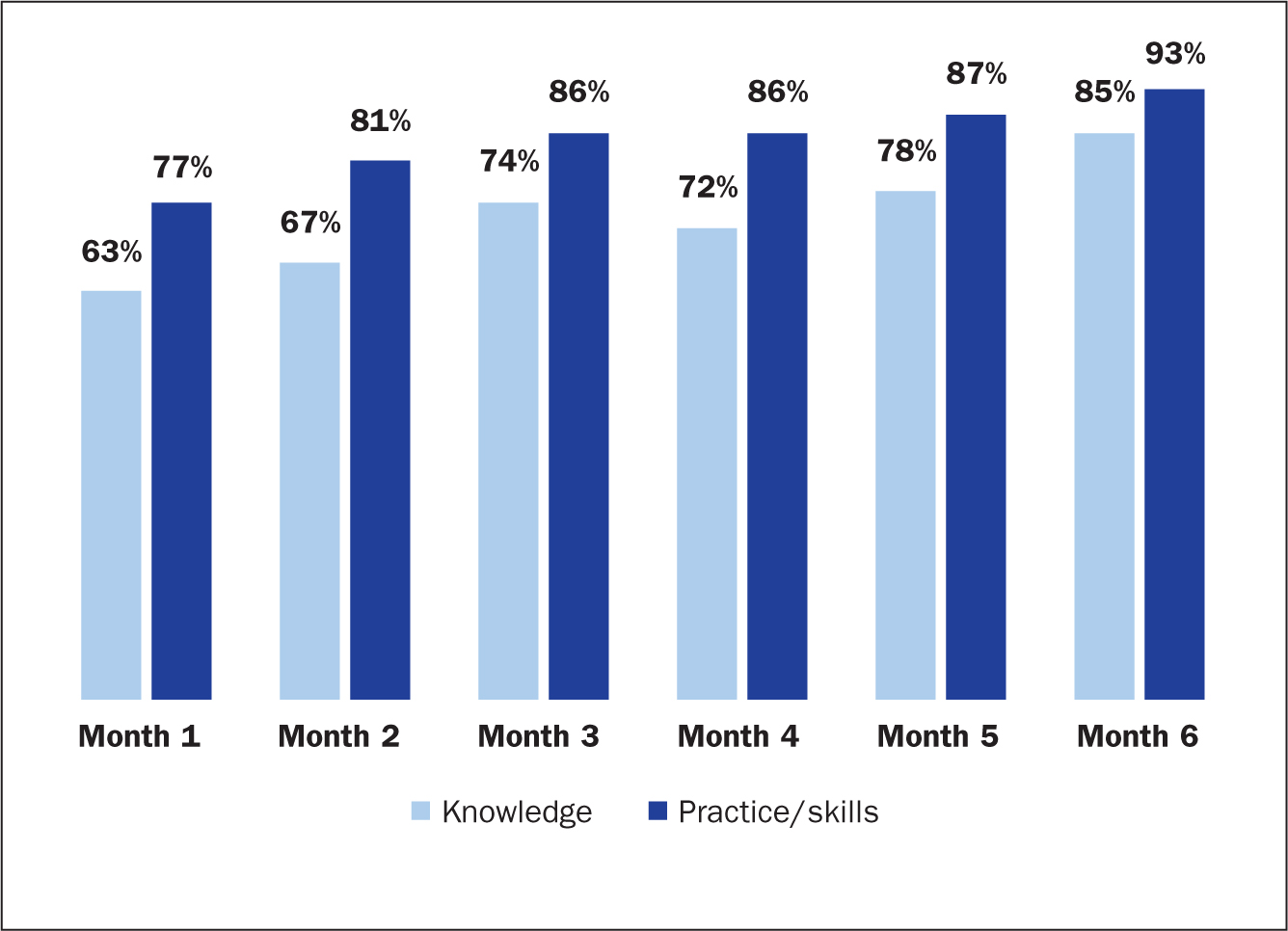

Knowledge levels on the VAD placement and maintenance areas mentioned above increased steadily to reach 85% by month 6 from 62% at month 1. Effective practice or skill levels at the time of assessment during the first month of the audit were 77% and made consistent progression to reach 91% by the end of month 6 (Figure 5).

Discussion

Principal findings

Education and training processes for nursing staff are heterogeneous around the world, leading to variability in competence. Nonetheless, nurses are pivotal in reaching the goal of high-quality healthcare for all. Continuous knowledge and skill enhancement through organisational learning, supported and empowered by hospital leadership, could result in safer care with lesser undesired events.

The PRIME initiative takes a programmatic approach towards raising awareness and training on key skills and clinical practices, with monthly audits to monitor compliance and monthly consultations with experienced experts (the JCI consultants). Each of these elements made a significant contribution to raising awareness, identifying areas for improvement and implementing strategies for improvement. All had been thoughtfully put together and the rise of 29% in cumulative compliance over 6 months is a sign that this approach has worked in improving knowledge, skills, and behaviour.

Interpretation within the context of the literature

Bartman et al (2018) demonstrated that systematic training, with teams deployed to educate staff in data management and analysis improved competency with productivity gains over time.

Lyren et al (2017) showed that implementing best practices and fostering a culture of safety improvements resulted in a decline in hospital-acquired conditions and serious safety events. In a multicentre setting, harm was reduced in eight of nine common hospital-acquired conditions (range 9%–71%; P<0.005 for all), while the mean monthly serious safety event rate declined by 32% (from 0.77 to 0.52; P<0.001) and the 12-month average serious safety event rate fell by 50% (from 0.82 to 0.41; P<0.001) (Lyren et al, 2017). The prevention of errors in nursing and improvement in care quality depend on adhering to the principles of patient safety (Vaismoradi et al, 2020).

A study covering 716 172 inpatient discharges at 24 hospitals revealed that a reduction in inpatient harm is associated with a shorter length of stay, and lower mortality and readmission rates. Harm reduction corresponded with lower costs and greater profit for hospitals (Adler et al, 2018). Out of the 237 million medication errors in England every year, 66 million are potentially clinically significant. Secondary care ADEs have led to longer hospital stays inflicting a cost burden of £14.8 million (Keers et al, 2015).

Implications for policy, practice, and research

It is hoped that, with education and expert consultation and guidance, clinical staff including nurses would be better equipped to identify, interrupt and rectify errors, resulting in better patient outcomes (Gaffney et al, 2016). Besides reducing incidents leading to patient harm because of human errors, the PRIME programme may reduce costs.

Strengths and limitations

The PRIME programme audit results indicate that adopting a systematic approach to education, training in best practices and implementing them in the real world with systematic monitoring and support yield positive results.

This programme was the only one of its kind attempted in Asia involving seven countries and 21 hospitals and their staff at various levels.

The results are encouraging and showed improvement in all parameters at all centres. If a homogenous programme is made available in the local language with common goals, standard operating procedures and monitoring standards, this can result in a noticeable difference in clinical practices by bringing about attitudinal changes through structured training mechanisms (Keers et al, 2015).

However, the PRIME programme requires further investigation into minor nuances to assess whether the ongoing knowledge and training drive directly resulted in skill levels increasing or some other factors were also responsible for the phenomenon. Nevertheless, the data furnished by 19 hospitals out of the 21 hospitals where the programme was implemented provide a fair overview of the impact on the chosen parameters.

Nonetheless, this was a controlled experiment confined to tertiary hospitals. It remains to be seen whether such an initiative can be sustained in the long term on its own and becomes an integral part of processes followed in these hospitals. The results, although encouraging, require greater validation through research involving more participants and hospitals, and in more places.

In addition, a follow-up independent audit is recommended to determine whether the improvement in safety in nursing procedures is sustained beyond the audit period.

No quantitative estimates regarding impact on cost reduction or patient outcome were estimated.

Conclusions

The PRIME programme was successful in improving patient safety through enhancing nurses' knowledge and skills.

This success was down to PRIME's unique features, including engagement at the leadership level of the hospital, the 6-month duration of the training and learning to implement new skills, and the training being delivered to bedside nurses by trained and experienced clinical consultants. Progress was measured using an audit tool, and steps were taken with auditing to minimise bias and to not link performance with specific nurses. Hospital champions could call JCI consultants to get more information, advice on any problems and ways to improve.

The approach and the tools can be employed as a continuous quality improvement initiative for prevention of medication errors and infusion-associated complications. The authors hope this model becomes a part of hospitals' policies and a routine part of continuous improvement for healthcare leaders. It would be beneficial to see this programme implemented further in Asia and become a sustainable initiative on its own.

All participating hospitals believe in continuous improvement and anticipate that a task force will be created to review the learning from and scope of the programme as well as the endpoints, with a potential addition of cost-effectiveness, with an emphasis on the need of similar programmes for patients' safety.

KEY POINTS

- Adverse effects in hospital are common, and often result from unsafe care around medication errors and vascular access device complications

- Medication errors and hospital-acquired infections are the two top risks associated with hospitalisation

- A programmatic approach, such as that adopted for PRIME, can instil the rigour and practice of continuous improvement in multiple countries and diverse cultures

- Change in practice and outcomes require requires staff ownership, backed by a strong commitment from leadership

CPD reflective questions

- Which standards and practices help minimise the risks associated with hospitalisation, especially around medication error and intraveous administration?

- Would having standards in place and ensuring staff have adequate knowledge and skills be enough to address these risks?

- How can hospital leadership contribute to building a non-punitive culture?

- How could you ensure knowledge is applied to bedside practice?