Diabetes is one of the most common long-term conditions in the UK; it can lead to multiple health problems for patients and costs the UK approximately £14 billion a year (Hex et al, 2024). According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2022; 2024), it is estimated that approximately 4.7 million people in the UK have diabetes and 90% of these have type 2 diabetes. By 2030, this is expected to have risen to 5.5 million.

When reviewing nutrition in the UK, a study by Bird et al (2022) found that most of the population aged >11 years do not receive an adequate intake of specific vitamins and minerals. This includes the following minerals: calcium, iodine, iron, magnesium, potassium, selenium, zinc; and the following vitamins: riboflavin, vitamin B6, vitamin D and vitamin A (Bird et al, 2022). This may be owing to the UK food environment, socioeconomic issues and a lack of education regarding nutrition (Stanner et al, 2023). It could also be attributable to the overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, which make up nearly 60% of UK adults’ daily intake (Dicken and Batterham, 2022). Regardless of the reason or cause, it is clear that patients, especially those with diabetes, require advice regarding diet and nutrition.

It is difficult for health professionals to advise patients on the most suitable nutrition therapy. Unfortunately, evidence suggests that there is no ideal calorie consumption percentage from specific food groups such as carbohydrates, protein and fat for people with diabetes (Evert et al, 2019). Numerous individual factors must be considered, including dietary and cultural preferences, meal preparation time, work and family dynamics as well as finances. Evidence supports dietary and lifestyle changes at the initial stages of diabetes diagnosis and as needed throughout the development of the disease (Evert et al, 2019).

This article aims to explore a range of diets and nutrition programmes recommended for patients with diabetes to support clinicians in their advice and allow patients to choose a nutrition option that is best suited to their lifestyle.

Mediterranean diet

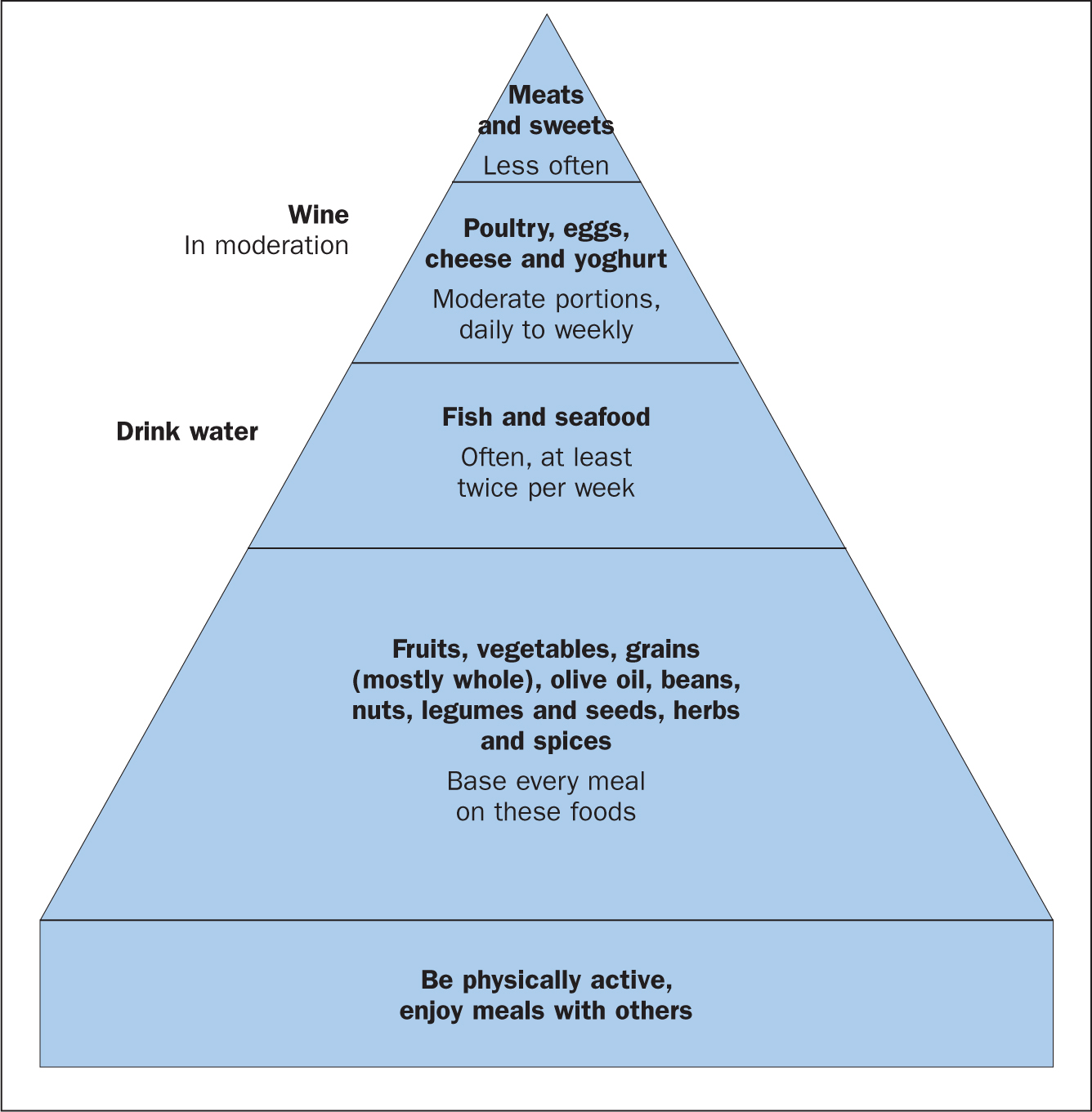

The Mediterranean diet has been recommended not just for patients with diabetes but also for the wider public owing to its cardiovascular benefits (Lima do Vale et al, 2023). This diet consists of a high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes and beans, with a lower intake of animal proteins, in particular red meats (Lima do Vale et al, 2023). Figure 1 outlines the food types portions recommended within the Mediterranean diet.

The Mediterranean diet is generally recommended as it has a higher proportion of unsaturated to saturated fats, with the use of plant-based oils such as olive oil replacing butter and margarine, and reduces the dependence on largely unprocessed foods (Ventriglio et al, 2020). Another benefit of this diet is that it is not restrictive and does not require the patient to calorie count or reduce calories, which makes it an easier diet to follow (Lima do Vale et al, 2023).

The limitations to patients in adopting this diet in the UK can be related to sourcing Mediterranean-type produce in the UK. Owing to the difference in climate, patients may not be able to source Mediterranean-type fruits and vegetables. This may also affect the costs of specific products and patients may find them more expensive than more locally grown fruits and vegetables.

Nordic diet

The Nordic diet is similar in many aspects to the Mediterranean diet but it includes ingredients found more commonly in Nordic countries. This includes the replacement of olive oil with rapeseed oil, local vegetables found in Nordic countries and greater amounts of fish and dairy products.

Studies have found that the Nordic diet has been as effective as the Mediterranean diet in preventing metabolic conditions (Magnusdottir et al, 2017). These studies have also shown reductions in inflammation, lipid profile and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (Magnusdottir et al, 2017). The 2023 Nordic Nutrition Recommendations present dietary guidelines and advice for the public in the Nordic and Baltic countries (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023) (Table 1). This table is a general guideline for adults and does not specify amounts based on personal characteristics such as age, sex or weight. However, it should be noted that men have a larger calorie requirement than women with men requiring 2500 kcal per day and women 2000 kcal/day (Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), 2024).

| Food group | Grams (g) | Percentage of daily intake (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetables, fruit and berries | 600 | 48 |

| Milk and dairy products | 400 | 32 |

| Whole grains (wheat, rye, barley, wild rice, maize, millet, sorghum) | 90 | 7.2 |

| Fish | 60 | 4.8 |

| Red meat | 50 | 4 |

| Nuts | 25 | 2 |

| Oil (unsaturated vegetable oil) | 25 | 2 |

The main aspect of both the Mediterranean and Nordic diet is the promotion of high vegetable consumption with reduced intake of processed meat and ultra-processed food. These diets also promote the use of locally sourced, in-season produce. For patients in the UK, it may be more likely that they could adopt the recommendations from the Nordic nutrition guide in relation to similarities in climate and an assumption that this produce would be lower in cost if grown locally. The Nordic recommendations could be more realistically adopted and adapted by patients in the UK.

Similar to the Mediterranean and Nordic diet recommendations, NICE (2022) guidelines in the UK advise eating carbohydrates from fruit, vegetables, whole grains and pulses. They also advise eating low-fat dairy products and oily fish as well as limiting the amount of food that contains saturated fat and trans fatty acids. Unfortunately, the NICE guidelines do not specify grams or kcal per day or week of particular food groups, which may be helpful for patients who enjoy tracking their food consumption in this way.

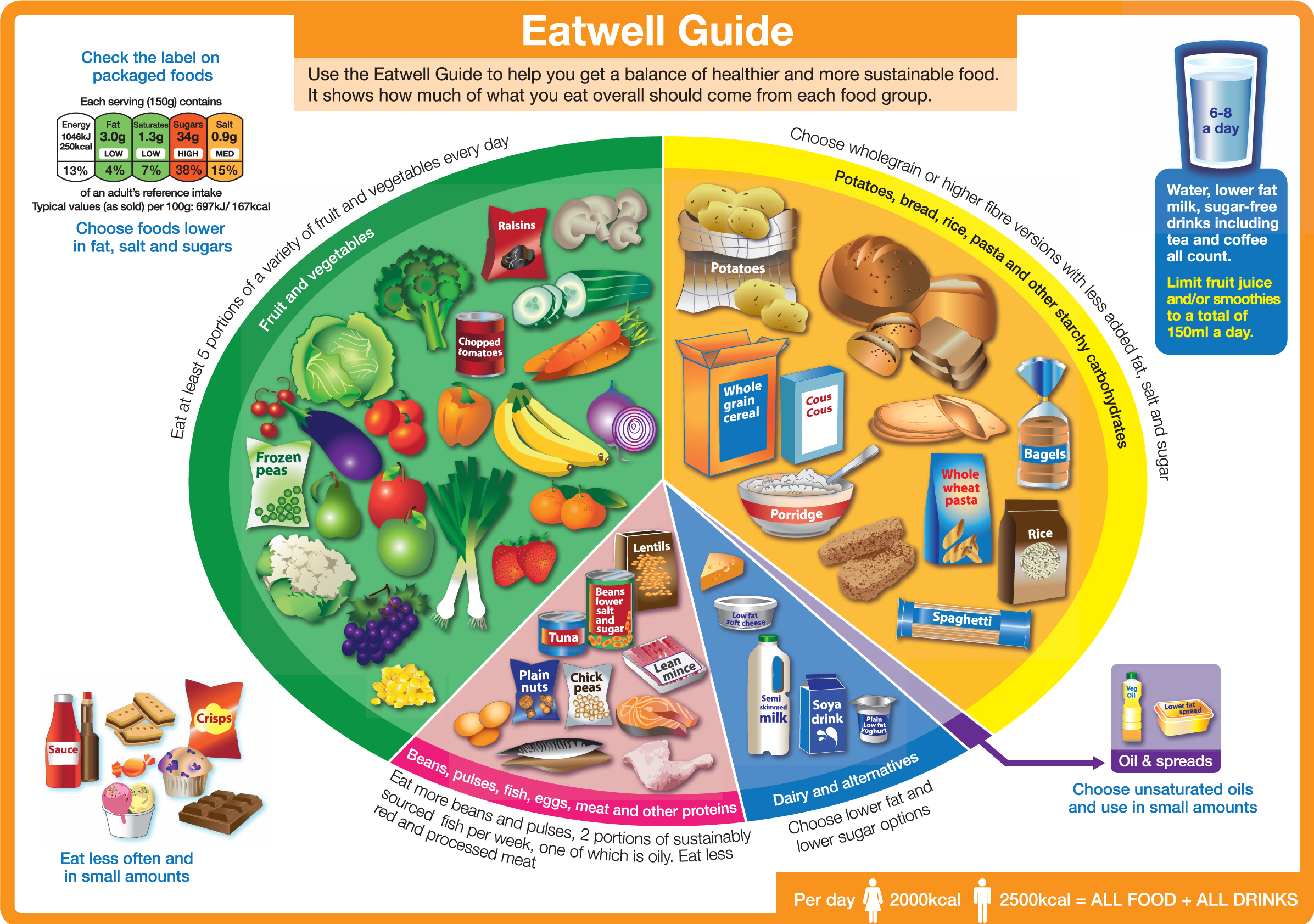

Figure 2 shows the Eatwell Guide, developed by the UK government to outline recommendations on eating healthily and achieving a balanced diet (OHID, 2024). It is straightforward to follow and people with diabetes or other patients requiring advice on diet can be signposted to this resource as a useful tool to support them to make better food choices.

Other nutrition options have been shown to be effective in weight loss, HbA1c reduction and, in some cases, reversal of a diabetes diagnosis. These diets are more restrictive and are based around low calorie consumption and restrictive eating to achieve the desired weight loss required to manage diabetes.

Low-calorie diet

The total diet replacement programme, which is available to patients with diabetes aged 18–65 years with a specific BMI target and a diagnosis of diabetes within the preceding 6 years, has been shown to lead to significant improved outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes (Evans et al, 2023). The total diet replacement programme has shown significant improvements in patients’ health, with one in three putting their diabetes into remission and an average weight loss of 16 kg (Lean et al, 2024). It comprises low-calorie consumption of 900 kcal/day for 12 weeks with the use of supplemental soups, shakes and snacks (Glenn and Liu, 2023). This is supported with weekly weighing and check-ins from health professionals. After the 12 weeks, patients are supported with nutritional reintroduction of food that they enjoy alongside exercise to maintain the weight loss (Evans et al, 2023).

Patients can be referred to this programme through their GP and, because of its success, it is now available across England. Additional benefits to patients of this programme are that it is free and it provides education around healthy eating habits.

Intermittent fasting

Intermittent fasting has gained popularity in recent years with the introduction of several fasting schedules. Intermittent fasting refers to a person not consuming any food or having a low calorie intake for a specific period. This can include different fasting regimens such as alternate day fasting where patients fast one day then eat the next or the 5:2 diet, a periodic type of fasting where patients fast for 2 days of the week (Albosta and Bakke, 2021). The most common type of fasting is the time-specific fasting method, where patients only eat in a restricted time window such as 12pm–6pm daily.

Evidence is conflicting on the benefits of intermittent fasting. Some studies have shown a reduction in weight with no change in HbA1c but others have shown improved insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, stress and appetite (Williams et al, 1998; Carter et al, 2016; Corley et al, 2018). There is clear evidence that reducing calorie consumption reduces weight and improves metabolic health; however, studies have shown people find reduced calorie consumption difficult to sustain over a period (Most and Redman, 2017).

While some evidence supports this as an option for patients with and without diabetes, certain considerations need to be taken into account when advising patients on this approach. Health professionals who have knowledge and training around intermittent fasting should advise patients of safety precautions required to prevent hypoglycaemic events. Care should be taken when discussing and advising patients on any insulin and any other form of hypoglycaemic agent in relation to intermittent fasting. Regardless of the amount of calories consumed, patients should be strongly encouraged to consume a nutrient-rich diet and adequate protein during their intake times (Albosta and Bakke, 2021).

The low-calorie diet programme and intermittent fasting may not be suitable for every patient. A full health check is required, ensuring no exclusion criteria apply such as pregnancy, immunodeficiencies or a history of eating disorders. Individuals with regular hypoglycaemic episodes should not be encouraged to partake in diets with reduced daily calorie consumption.

Medical nutrition therapy

Medical nutrition therapy can be used in conjunction with changes in dietary habits and plays a crucial role in managing type 2 diabetes (Barrea et al, 2023). Medical nutrition therapy aims to provide patients with the knowledge and promotion of healthy eating habits, so they can self-manage their diet through healthy eating habits and portion sizes, as well as supporting the pleasure of eating food while limiting food choices that have been shown to have negative impacts on health (Evert et al, 2019).

With dietary training and advice, health professionals can advise patients with diabetes on individual nutrition therapy within their structured appointments. Barrea et al (2023) outline common features previously mentioned, such as choosing non-starchy vegetables, reducing sugars and refined grains plus increasing wholefood consumption and avoiding highly processed foods.

Precision nutrition takes this one step further and aims to tailor treatment to patients’ individual characteristics. This would entail having individualised diet plans based on a patient's specific characteristics, microbiome, genome sequence, health history, lifestyle and diet (Wang and Hu, 2018). The PREDICT 1 study outlines how this type of individual nutrition therapy, closely monitored by the patients themselves, supports and improves their understanding of foods that raise glucose levels as this can be different for everyone. The therapy can reduce inflammation, lipids and glucose levels (Berry et al, 2020). However, Wang and Hu (2018) warned that more evidence and data are needed to understand the efficacy, cost-effectiveness and additional benefits of precision nutrition beyond the standard advice around diet and exercise. Although there have been positive developments with precision nutrition, it is not a nutritional approach currently supported in the UK and is not listed as an option for patients with diabetes in any UK guidelines. Patients may request advice around this and health professionals should be cautious in their response to patients regarding this option.

Physical activity

Diabetes management cannot be discussed without also mentioning physical activity. Nutrition and diet options have been outlined and evidence supports dietary changes with an emphasis on vegetables, fruits and wholefoods to manage diabetes. However, physical activity is also a crucial factor and it has numerous health benefits for patients with diabetes (Colberg et al, 2016).

Physical activity has been shown to improve cardiovascular health, reduce weight, reduce cholesterol and improve mental health (Davies et al, 2019). Patients with diabetes should be encouraged to engage in physical activity and exercise regularly. Weight-based training has been shown to improve glycaemic levels and enhance insulin action (Colberg et al, 2016). The UK chief medical officers’ physical guidelines (2019) recommend 150 minutes of moderate-to-intense physical activity per week (Davies et al, 2019). Patients should be encouraged to engage in different forms of physical activity regularly to support their health management throughout their life (Davies et al, 2019).

Summary

The diets and nutritional options suggested in this article are to be used as a guide and certain options may be more appropriate to certain individuals. There may also be circumstances where one option is appropriate at a certain time in a patient's life; this could be following the low-calorie diet programme before continuing with a balanced diet such as the Nordic or Mediterranean options (Glenn and Liu, 2023). Professionals should incorporate diet and nutrition discussions when reviewing patients with diabetes at every contact and discuss the options available to them.

Although nutrition is a very important aspect of diabetes advice and management, other factors may be affecting a patient's health. These could include previous medical history, comorbidities, sleep, mental health, occupation, social life and family. Patients will not be willing or able to change their nutrition habits if other aspects of their life are not functioning. Health professionals must explore these factors and understand the contributing factors to lifestyle changes through a patient-centred approach.

Health professionals can use SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and time) goals to develop a care plan and advise more regular consultations to support these patients. Health professionals should also refer patients with other concerns to the appropriate support or professionals to manage other lifestyle factors affecting the optimisation of their health.