Digital technology includes electronic devices, systems and applications that are used to process and transmit information. These devices include computers, smartphones, tablets and smartwatches, which are linked to a variety of digital applications. The use of digital technology has become a major part of everyday life, including accessing health care. Terms such as telehealth, telemedicine, e-health and m-health have all made their way into modern health care, with the common aim to allow health professionals to deliver uninterrupted patient care and offer support to other clinicians remotely.

The practice of incorporating digital technology into healthcare began in the 1990s (Norris, 2001) and it has slowly become an essential part of caring for patients with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes in the NHS (Clark and Goodwin, 2010). Although not widely implemented, digital technologies, in particular virtual consultations, are globally recognised tools within stoma care (Bohnenkamp et al, 2004; Sun et al, 2018; White et al, 2019). In the UK, anecdotal evidence suggests that the use of digital technology in stoma care before the pandemic was limited, as the traditional approach in providing care has been predominantly through face-to-face interaction. Additionally, the authors’ hospital did not have the infrastructure to facilitate this practice.

COVID-19 recovery plans have led to the proposal of new recommendations for patient care and surgery (NHS England, 2020; Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCSE), 2020; Fearnhead et al, 2021). However, these are not specific to the complex needs of stoma patients. The Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK (ASCN) guidance on COVID-19 is fairly general, with recommendation to follow the advice issued by the government and hospital trusts/employers (ASCN, 2020), whereas the RCSE provides more specific recommendations, suggesting virtual consultations as the preferred tool for outpatient appointments where possible for the duration of the pandemic (RCSE, 2020).

It has been the universal principle for all healthcare institutions during the pandemic to prevent unnecessary exposure of health professionals and patients to the risks of contracting COVID-19 but, at the same time, to continue to provide high levels of nursing and specialist care. This is especially significant for stoma nurses, as numerous studies report that traces of the virus remain in the faeces and urine of COVID-19 positive patients and transmission is plausible (Brönimann et al, 2020; Chen et al, 2020; Sun et al, 2020; van Doorn et al, 2020; Wang et al, 2020). However, further studies are needed to determine whether the virus is viable and whether it can be transmitted through faeces and urine (Gupta et al, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). Because we do not have conclusive data to exclude possible transmission, it is best to adopt a ‘better safe than sorry’ approach.

Stoma services at the authors’ institution were considerably reduced during the height of the pandemci because specialist nurses were redeployed on wards to care for patients with COVID-19 infection. Vulnerable stoma nurses were advised to shield or work from home, while others were off duty, recuperating from COVID-19 symptoms.

The authors’ tertiary referral centre continued to do essential operations but most of these were performed off-site using private hospitals that had become redundant during the pandemic. Therefore, it was crucial to adapt the nursing service rapidly to continue to provide care to patients. Implementing digital technologies into the service was inevitable during this period.

To mitigate future risk to specialist nursing services, the authors’ team has embraced the concept of digital technology to improve patient-nurse interactions, communicate with the wider multidisciplinary team (MDT), interact with patients’ relatives or carers and to use it as a platform to enhance personal development, training and education.

This article describes the different modalities of digital technology implemented at the authors’ institution during the pandemic for inpatients and outpatients, as well as other service users (Table 1). Possible advantages and disadvantages are discussed, illustrating in more detail how the nursing service was transformed.

Table 1. Digital technologies

| Patient-centred digital technology | |

|---|---|

| Outpatient interactions | |

|

|

| Inpatient interactions | |

|

|

| Other patient-centred interactions | |

|

|

| Specialist nurse-centred digital technology | |

|

|

Despite the challenges of this pandemic, the stoma service was adapted successfully. This would have been impossible without digital technology.

Implementing digital technology in stoma care

Outpatient interactions

Virtual consultation via Attend Anywhere

Attend Anywhere is a national, licensed video platform funded by NHS England that provides secure, remote video consultations with patients (NHS website, 2021).

Attend Anywhere has ensured that patients are promptly reviewed so care is not missed or delayed. The authors’ team now routinely uses Attend Anywhere for pre- and postoperative support to empower patient to self-care, manage complications and avoid unnecessary hospital, GP or MDT appointments and visits to the emergency department (ED).

The advantages of using this platform are that it allows practitioners to hold video consultations with local, national and international patients including those who are housebound, frail or COVID-19 positive. It also avoids the costs of travel, overnight accommodation or hospital car parking fees and possible exposure to COVID-19.

The disadvantages are that it requires a good internet connection and access to a smartphone and/or other device with a web camera and a microphone. It may not be appropriate for people who do not have experience of digital technologies. If video quality is poor, it may lead to an incomplete assessment and inaccurate treatment.

In addition, the workforce needs to be engaged in this change and trained to acquire skills so they are able to use the platform. Investment is needed in good-quality electronic devices for stoma nurses, as well as forward planning to ensure office/clinical areas provide a private and quiet environment to ensure patient confidentiality, avoid distractions and prevent possible errors.

Telephone consultations

Telephone consultations are a well-established method of accessing and sharing information or providing reassurance from a familiar voice. When used with a translation service, telephone interactions may assist with language barriers.

Patients and members of the MDT are able to receive immediate or emergency advice via the stoma service’s telephone advice line. It has also been an essential part of pre-operative stoma counselling during the pandemic. Additionally, the authors’ team offers routine postoperative telephone reviews via Secure Start, an advice and support service provided by an external stoma appliance manufacturer (Hollister) to new patients on discharge. This has been extremely useful during the pandemic because many patients were discharged quickly to prevent unnecessary exposure to coronavirus.

An advantage of this is daily access to a trained telephone adviser. Concerns are actioned or escalated directly to a stoma nurse. Most people own and can use a telephone.

However, full assessment may not be possible if visual interaction is required. Occasionally, the telephone may not be answered immediately and, if a message is left, it may be difficult to understand or missing vital information. Some patients may not want to leave a message or may not be able to understand the instructions on the answerphone.

As some telephone support is received from an external provider, it is essential to ensure that patient privacy is not compromised. Dedicated time needs to be allocated for nurse-led telephone clinics and telephone queries.

Email consultations

Written and photographic information can be shared quickly using a safe, generic stoma care email to resolve non-urgent problems, provide reassurance and support, as well as seek clinical advice on more complex concerns which may require escalation. It is easy to access stoma pictures or videos of complications and devise a treatment plan.

There is no need for both parties to be available at the same time. Patients can receive advice rapidly from the generic email, which is checked throughout the day by the team including administrative staff and can be accessed remotely by nurses working at home or shielding.

However, multiple emails may be needed to obtain the necessary information. Emails may be lost, end up in spam folders or an incorrect email address may be entered. Personal emails are not secure and patient confidentiality can be breached. Email correspondence is not usually used for emergency advice because there may be a delay in replying due to clinical work taking precedence.

It is not guaranteed that the practitioner will be emailing the right patient and extra precautions should be taken, such as replying via a telephone or virtual consultation. Protected time is needed to answer emails without distractions because some require careful interventions and clear clinical documentation.

Digital patient information

Traditionally, patients were provided with written information during face-to-face appointments. During the pandemic, this was not always an option and posting information took considerably longer, so the practice of emailing digital copies of written information, as well as providing information on our website, was adopted.

The advantages of this include that easily accessible information is promptly delivered to a patient’s email, and patients have enough time to process the information and ask relevant questions. The cost of postage and printing is avoided.

However, some patients may not have access to email and there is no guarantee that patients have received or read the information. A database may be required to capture patients’ email details.

Prescription review for local patients

Harrow Appliance Prescription Service (HAPS) is a service provided by an external company (Connect/Fittleworth) used to manage the prescription requirements of stoma patients in the community in rapid-access clinics, during routine follow-up appointments and annual patient reviews, which reduces the GP workload and maintains cost efficiencies. HAPS also prevents delays in prescriptions for new patients.

The advantage of this is uninterrupted prescription management, dispensing and delivery, covering the complete pathway of care from hospital to home.

However, it requires extra workforce training, documentation and monthly auditing to manage the prescribing elements in stoma care, as well as collaborative working with the HAPS team.

Inpatient interactions

Video call stoma care teaching

This involves using the patients’ own smartphone or other video-calling device to interact with patients’ relatives during stoma teaching sessions on the ward. For those without a device, the hospital has invested in an iPad, using Virtual Visits, which is a secure, hospital-approved application (Figure 1).

Many hospital wards have implemented strict restrictions on visitors during the pandemic. Introducing video calling has allowed relatives to offer emotional support to their loved ones, as well as provided the opportunity to learn stoma care.

The caregiver/family member has the opportunity to learn by observing the appliance change and asking questions related to their home setting. Nurses are able to provide holistic care and be reassured that patients can be discharged safely and in a timely manner. It may even avoid the cost of registered carers to assist with stoma care.

A downside is that family members and caregivers only observe stoma teaching so their skills cannot be assessed. Poor internet connectivity on wards may lead to failed sessions or multiple teaching sessions being required.

This also requires investment in digital devices, with built-in cameras and microphones, and in training on using the new devices for stoma nurses.

Videorecorded step-by-step care plans

Using the patient’s own smartphones or other videorecording device, the stoma nurses were able to create video step-by-step care plans for stoma/fistula management after discharge.

Video technology has allowed nurses to empower patients and family members to self-care. These care plans offer audio and visual prompts and can be paused during appliance changes to ensure the care plan is followed correctly for both basic and complex stoma/fistula care. Patients can also share them with their local stoma nurse or carer.

Video care plans can be a useful reminder if a patient or carer is unable to speak to a stoma nurse.

The plans can be saved on any digital device and shared as necessary. However, video care plans can be accidently deleted so alternative care plans should be considered. The files can also be large to share or store. In addition, devices need to be charged to ensure adequate battery life during use.

Other patient-centred interactions

Local and national support groups

Using digital platforms such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams stoma nurses can connect with their local and national support groups at a time when nursing support is often limited, patients feel isolated and there is increased concern and anxiety. Practitioners can attend committee meetings or present topics of interest at virtual patient information days.

This allows virtual meetings with large groups of people when social distancing is in place. Everyone can attend from the comfort of their home, no venue has to be booked and it removes the time and costs that would normally be required for travel and overnight accommodation. Meetings can be recorded and shared online for participants who were unable to attend.

However, not everyone has access to electronic devices or knows how to gain access to enter the meeting. Some may feel intimidated, not know how to interact or even interrupt the meeting by not being able to mute personal devices. Virtual support meetings do not allow people to interact fully with each other.

Investment is needed to train the workforce on using the devices and applications, and to improve digital literacy.

Remote working from home

Digital technologies have proven essential not only for our patients but also for the workforce, allowing practitioners to be more flexible, responsive and provide direct patient care even when shielding or working from home.

Stoma nurses can provide some clinical and non-clinical interventions to patients, and continue professional development, education, research, audit and management aspects of their role from home.

Patient confidentiality is maintained in accordance with the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2018a) code of professional practice by using secure trust technology such as mobile phones and laptops with virtual private networks, and patient data stored or transported in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018.

With a reduced or redeployed workforce, the stoma nursing team had to consider how best to utilise its vulnerable colleagues, as well as reducing risk of COVID-19 infection by socially distancing in offices and avoiding non-essential journeys to work.

Working from home allows vulnerable members of the team to continue to support the workforce and their patients. When possible, rotating between working in clinical environments and at home may relieve the pressure for frontline nurses, as working from home allows a better work/life balance and reduces stress and sickness (Samek Lodovici et al, 2021). Additionally, working from home may help reduce burnout (Hoffman et al, 2020). Some nurses in the authors’ team, in line with nationwide findings, felt guilty about the increased pressure placed on colleagues based in clinical areas, and working from home increased their contribution to the workforce (Chattopadhyay et al, 2020).

However, office infrastructure at home is not always available or suitable. Bills for heating and electricity rise, and a faster internet connection may be needed. Work is limited to jobs that require digital technology and may be more time consuming to complete remotely. Long periods of time sitting and using technology are required, which may cause discomfort, eye strain and musculoskeletal problems over time (Moretti et al, 2020). Managers need to be able to trust staff to work effectively at home.

Some members of the team feel that they are more efficient and work better and for longer without workplace distractions, which correlates with the general literature (Samek Lodovici et al, 2021). However, several studies have reported decreased wellbeing, reduced motivation and negative experiences when working from home (Moretti et al, 2020; Xiao, 2021).

Working from home often means balancing work with looking after extremely vulnerable family members and/or providing child care or home schooling, which can be difficult. Family members need to be advised when consultations are in progress to avoid disruptions and maintain patient confidentiality. Nurses working from home should use a designated quiet and private area to ensure that patient’s privacy and confidentiality are not breached.

Enhanced communication and co-ordination

To continue to perform vital colorectal operations and prevent further treatment delays during the pandemic, elective surgery was carried out at five separate hospital sites. Implementing digital technology was crucial to communicate with patients, the stoma team and the wider MDT to co-ordinate care and ensure patient and staff safety. This was especially important to co-ordinate stoma appointments with other appointments to prevent patients attending for multiple hospital visits.

Secure, NHS-approved devices and applications were used to exchange digital information, such as changes to admission lists or to arrange pre-assessment and stoma siting consultations.

Communication is vital to the success of any stoma service. However, with so many changes to the service and within the workforce, it was paramount to prevent miscommunication and make systems as easy as possible to navigate. Digital handovers and documentation templates were designed and implemented with the increased use of laptops and telephones to co-ordinate and communicate effectively.

As a result of this change, patients were prepared and sited for a stoma in a timely manner with less room for error, clinical incidents and patient complaints being raised. Workforce planning was easier to co-ordinate.

A downside is that a connection that is poor or fails may delay communication between team members in different locations.

Implementing changes to established workplace culture, patterns and processes takes time and some members of the team may not be able to become proficient with digital technologies as quickly as others. Specific stoma nurses had to be assigned duties solely to co-ordinate patient admissions and communicate with nurse colleagues, which took them away from clinical care.

Continuing personal and professional development

Learning forums via digital devices and applications allow nurses to update knowledge and skills through virtual conferences, webinars/webcasts and in virtually conducted university classrooms. These are used to keep up to date with protocols, policy and guidelines, as well as to gain information needed for revalidation.

Nurses can attend these while at work or at home and at a pre-arranged time, so more people can take part. Technology provides more opportunities to attend local and international educational events without incurring the costs of travel and accommodation.

However, some people may find it difficult to learn outside a classroom or may be less motivated and more distracted at home.

The workforce must be given the time required to continue to update their knowledge and skills even during a pandemic.

Virtual teaching for other health professionals

The authors’ hospital is a teaching hospital and, before the pandemic, it was providing face-to-face training for local, national and international health professionals. During the pandemic non-essential roles such as teaching were suspended; however, mid-pandemic, the hospital was able to reinstate some of this work remotely via applications such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams.

The stoma team was able to share guidelines and protocols with other institutions to assist with management of patients with more complex needs, as well as liaise with national and international stoma nursing support networks.

This allowed practitioners to reconnect with the world not only to share knowledge but also to learn from other health professionals and cultures. This has been beneficial because it allowed staff to understand how different stoma teams have coped during the pandemic to retain and improve their services.

A disadvantage of virtual teaching is that it provides limited opportunity for stoma care skills to be assessed properly. Live presenting or being pre-recorded, with or without an audience, is new to even experienced nurses. Some nurses have had to learn techniques to keep the audience engaged and initiate discussion afterwards.

Reflection and discussion

The pandemic has required nurses to implement digital technologies and, at the same time, demonstrated its many benefits to modern health care, as future nurses would be expected to adapt to a constantly changing and innovated clinical environment (NMC, 2018b).

However, the success of digitalised nursing requires investment and education of both service users and providers, given Health Education England’s (2018) predictions that digitalised nursing services will be an integral part of the NHS within 5–10 years and reaching full optimisation in 20 years.

This pandemic has revealed that digital technologies can help reach patients anywhere in the country or globally, where access to specialist services is not always available, therefore providing equity in access to specialist care. This practice has already been adopted successfully for other services across the world, providing specialist care to patients in remote areas, while avoiding unnecessary travel and its associated costs, as well as disruption in day-to-day life (Sabesan et al, 2012; George et al, 2014).

Moreover, digital technologies help reduce GP and ED visits, face-to-face outpatient appointments and missed appointments, as well as having the potential to reduce healthcare costs. They also improve the patient experience and empower people to self-care (NHS Commissioning Assembly, 2015; Vijayaraghavan et al, 2015). Additionally, digital interactions can help reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure because direct face-to-face contact is avoided in accordance with government guidelines.

During these unprecedented times the stoma nurses implemented digital technology to provide effective and evidence-based care for patients and colleagues, maintain their safety and wellbeing, while updating clinical and digital skills. The team has ensured that introducing new technology has been advantageous to most patients and highlighted advantages, disadvantages and other considerations before implementing these measures to avoid harm and breaches in patient confidentiality in accordance with the NMC code (2018a).

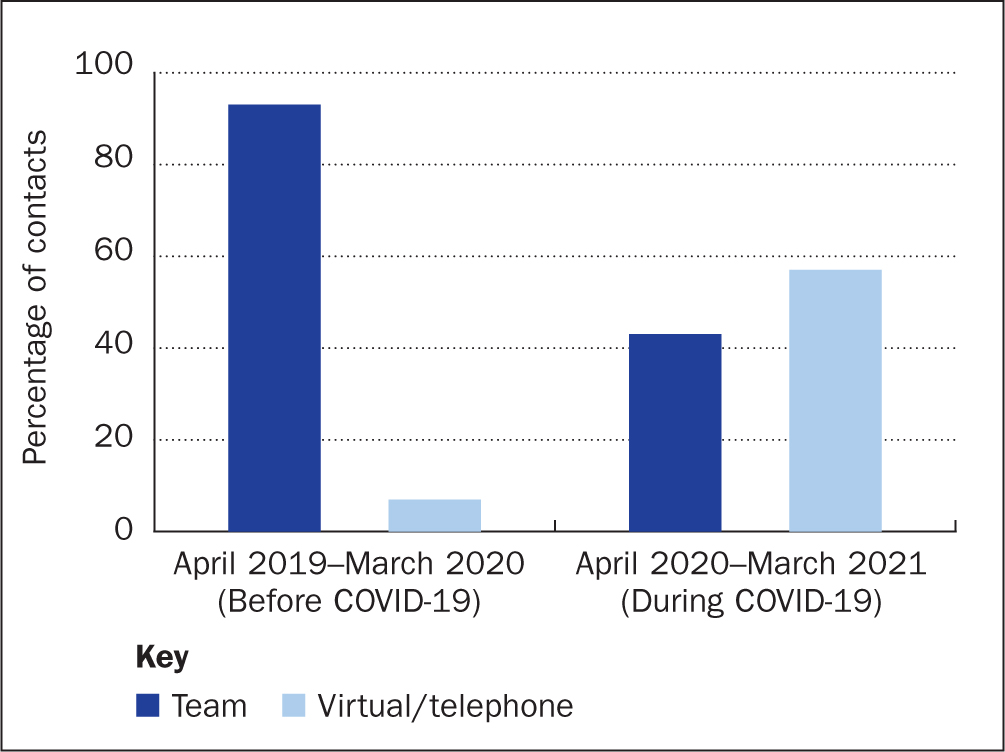

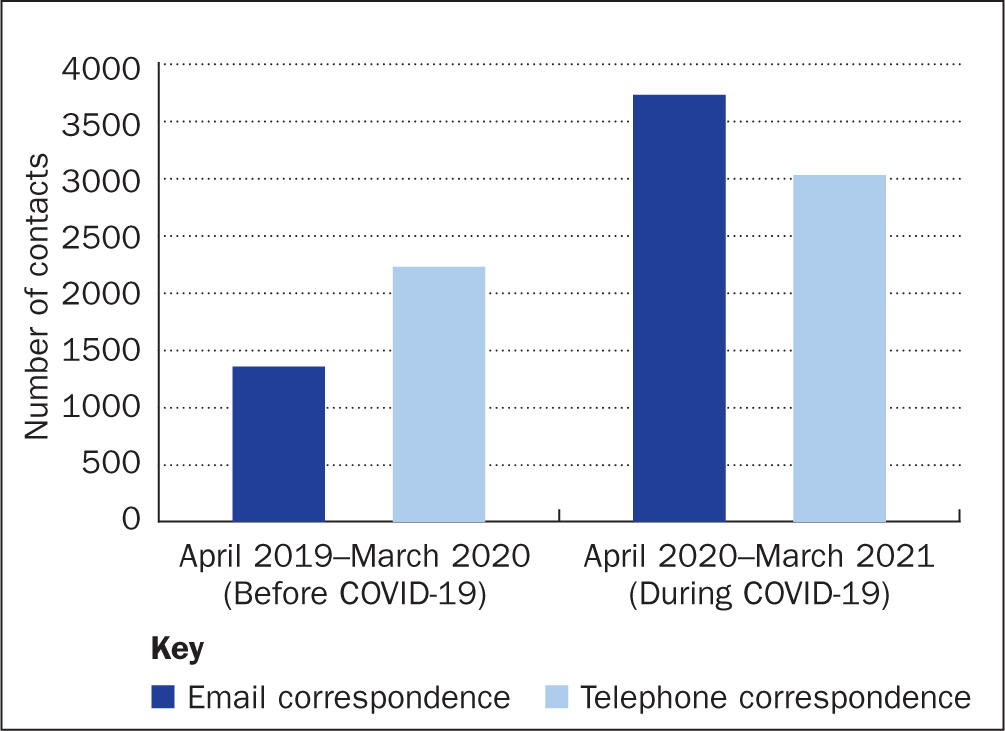

During the pandemic, the numbers of outpatient clinic appointments remained approximately the same at our institution, although patient interaction through digital technology (virtual and telephone) superseded face-to-face consultations, with a significant increase from 7% before COVID-19 to 57% during the pandemic (Figure 2). There was also a significant increase in our email and telephone MDT correspondence during the same period (Figure 3).

Digital technology can help fill gaps in service provision, such as the inability to provide face-to-face interaction, as well as reduce incidents of missed clinical reviews, assess and treat complications, and provide psychological support, stoma teaching and continuity of care (Bohnenkamp et al, 2004; NHS Commissioning Assembly, 2015; Sun et al, 2018; Dewsbury, 2019; White et al, 2019), when access to face-to-face clinics is limited or reserved for complicated cases that cannot be managed remotely.

The legalities and possible consequences associated with digital technology should also be considered. As digital technology has been rapidly integrated into our health care over the past year, we need to ensure safe practice to prevent poor outcomes, such as misdiagnosis due to poor picture and audio quality. Therefore, it is paramount that service-specific policies, guidelines and documents related to information governance are followed to safeguard patients and service providers.

Patients’ privacy and confidentiality are serious concerns when implementing digital technology in health care, as information can very easily be disseminated to many people. It is the responsibility of all health professionals to ensure that privacy and confidentiality are maintained, as well as informing patients of the possible risks of using digital technology (Sarhan, 2009; NMC, 2018b). Guidelines have been produced for health professionals covering remote working and consultations for patient management in response to COVID-19 pandemic. This is to ensure that principles of good practice, patient confidentiality and data protection are applied and adhered to (Royal College of Nursing, 2020; NHS website, 2021). When working from home, practitioners should take measures to maintain confidentiality (for example using headphones), as well as working in an area where privacy and patient confidentiality are guaranteed.

Digital technology interactions in stoma care are fairly new and the authors do not currently have enough data to compare the outcomes of digital and face-to-face interactions with previous modes of working. Reassuringly, though, it appears that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages, especially during a pandemic. There is still a pressing need to audit how efficient digital interactions are in stoma care by focusing on patient-centred feedback as opposed to health professionals’ interpretation of outcomes to improve and future-proof the authors’ service.

The stoma nurses have made great progress in managing patients during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, they do not have evidence that the care the patients received was the best possible. The team still needs to reach more vulnerable patient groups to ensure that all can access digital services or at least not be disadvantaged if they are unable to use digital technology, as several studies have discussed (Mehmi et al, 2020a; 2020b). Investment in education and infrastructure for these groups is needed. Mehmi et al (2020b) suggested some interesting solutions, such as healthcare teaching programmes for patients who are not very proficient with technologies and installing free, soundproof booths with access to digital devices in community centres, GP surgeries or libraries to ensure access to consultations, as well as for patients who live in households where privacy cannot be guaranteed.

Although digital technology interactions may appear to be the way forward, the importance of a face-to-face interaction in certain patient groups should not be underestimated.

Critics may argue that digital technology takes away the personal touch; however, it may actually add the personal touch that is missing in a face-to-face interaction: the ability to see faces and expressions, which are usually hidden behind masks. Stoma nurses should not fear the new normal but embrace digital technology in health care. Digital technology cannot completely replace face-to-face interaction but it can definitely be used to help nurses to support patients. Even in complex cases, digital technology can help practitioners to manage a problem temporarily until a face-to-face appointment can be arranged.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an the opportunity to change the culture and beliefs that stoma patients cannot be supported without face-to-face interaction. Therefore, NHS trusts need to continue to invest in high-quality digital devices and infrastructure to provide more accessible digital technology interactions that are safe and consider patient privacy, as well as conform to the principles of information governance (Ortega et al, 2020). They should support nurses to work at home where possible and encourage a culture that supports flexible working and a positive work–life balance.

Digital technologies in health care have the potential to empower patients to take control of their care and to self-care (NHS Commissioning Assembly, 2015). The authors think that it is important to continue to use digital technologies to empower patients to self-care and know when it is appropriate to self-manage their conditions.

Moreover, by using digital technologies, the stoma nurses have been able to teach other health professionals new stoma care skills, as well as exchange information and share experience on research and stoma care practices with stoma nurses across the world. Such collaborations would definitely help enrich knowledge and help the stoma nurses to continue to provide evidence-based practice.

Conclusion

Although there is room for improvement, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown nurses that there are many ways to introduce digital technology to effectively support stoma patients, their families and medical colleagues, wherever they live or work.

Digital technology may have its drawbacks, but it should be offered as a first choice for suitable patients and definitely be considered in cases where a face-to-face interaction is not possible or essential. Although it is not suitable for everyone, there are clear advantages for future investment and education in its use.

Practitioners should continue to use digital technology for selected patients because it reduces costs and provides more time-effective and efficient patient care, as long as appropriate pathways and protocols are maintained for safe and effective use of these services. This is the opportunity to build on what has been learnt during this pandemic to use digital technology to provide satisfactory outcomes for all stoma patients.

KEY POINTS

- Digital technology helps to bridge the gap between restrictions on face-to-face interactions and helps maintain uninterrupted patient care

- Although stoma care has traditionally been provided face to face, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity to use technology to change culture, learn new skills, run cost-effective services and improve patient experience

- With the implementation of new technology and different ways of working, stoma nurses need to mitigate the risks associated with digital technology while being able to champion a culture that embraces digital investment

CPD reflective questions

- In the context of an ageing population and workforce, do you consider that digital technology is the most appropriate method of patient–nurse interactions in the future?

- Consider digital technology in your area of work and more widely. Does it offer a sustainable investment for the NHS after COVID-19?

- Consider whether digital technology provides the same degree of care and support as face-to-face interaction with patients?