According to the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Skin (2020) a skin disorder can be defined as a disease affecting the skin that can have an observable impact on the lives of both the person and their significant others. Most skin disorders are self-managed, with only 25% of the population using a healthcare resource, such as a GP, to manage their condition (All-Party Parliamentary Group on Skin, 2013). Current evidence specifies that managing patients holistically from the start of their illness reduces the physical and psycho-social impact of the skin disorder in the long term. In order to improve the care delivered training for nurses must include basic assessment and support for patients who present with skin disorders.

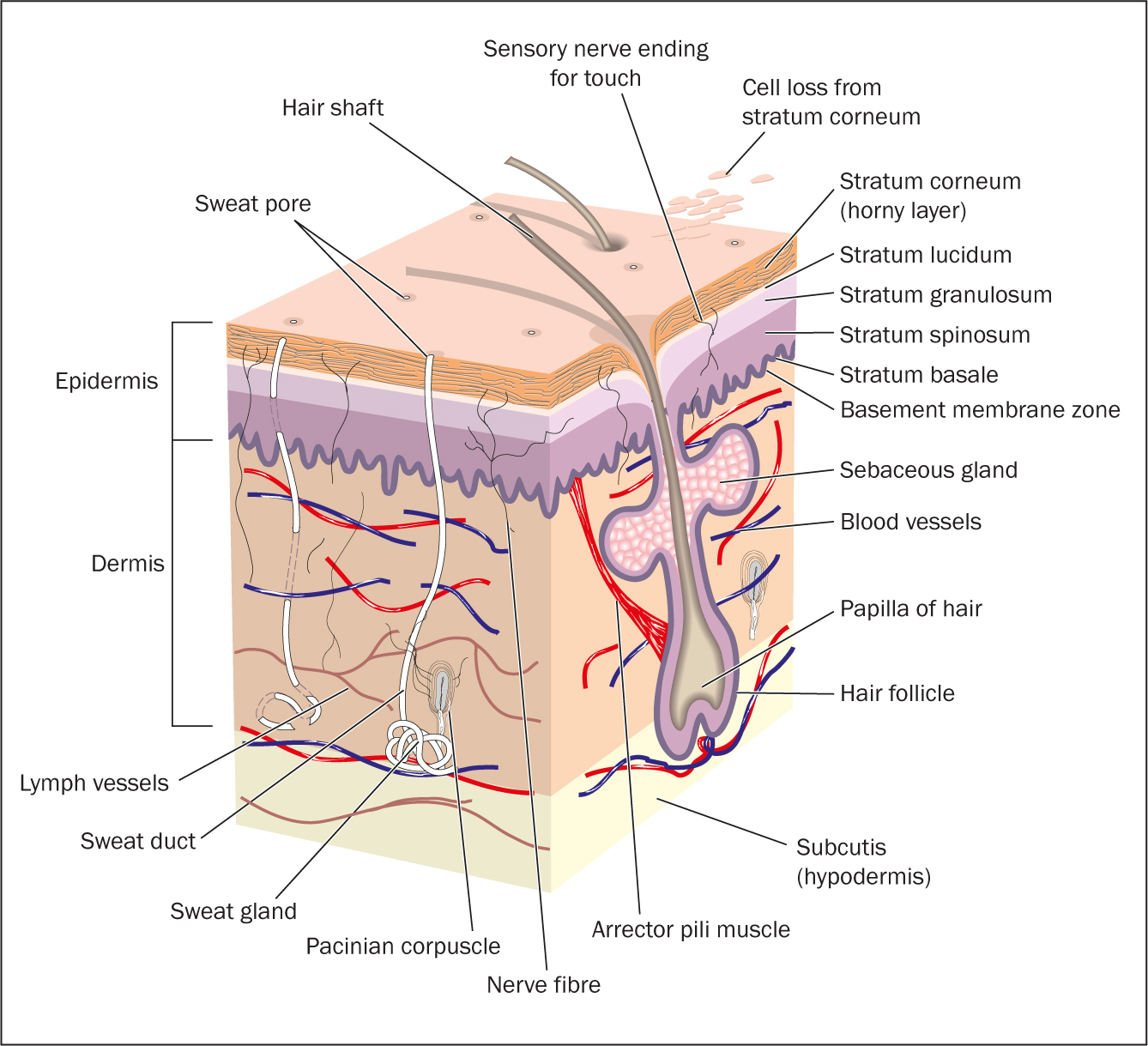

Overview of the anatomy and physiology of the skin

The skin (integumentary system) is the largest organ of the body, weighs 2.7–3.6 kg and has an average surface area of 1.9 m2. It also has many functions (Table 1) and is made up of the hair and nails as well as skin.

Table 1. Summary of skin function

| Function | Action |

|---|---|

| Protection | A protective function against:

|

| Sensation | Skin triggers a response through nerve endings that detect temperature, pressure, vibration, touch and injury |

| Synthesis of vitamin D | In the presence of sunlight, a form of vitamin D called cholecalciferol is synthesised |

| Excretion | The skin can remove waste substances and water from the body by sweating and water evaporation |

| Absorption | The skin can absorb certain vitamins, medications and gases |

| Storage reservoir | The skin acts as a reservoir to store blood |

| Regulation of body temperature | Protects the body from cold and heat, maintains a constant core temperature |

| Psychosocial | The condition of our skin affects how we feel about ourselves and how others view us |

The epidermis

Epithelial cells make up the outer layer of the skin, which is slightly acidic (pH 4.5–6); it is normally four to five layers thick, with more layers in the palms and soles. The epithelium has five layers: stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum lucidum, stratum spinosum and stratum basale.

Other cells found in the epidermis include Langerhans cells, which help other immune system cells to detect an infecting microorganism and destroy it, and tactile cells, which contain a disc that detects touch. Tactile cells are found in the fingertips, armpits, genital region and the soles of the feet.

The dermis

The dermis is the deepest layer of the skin: it contains hair follicles, sebaceous glands (which secrete sebum, an oil) and sweat glands. ‘Cleavage lines’ are found in this layer; these are genetically determined and unique for each person. Surgical incisions should run parallel to the cleavage lines, promoting healing with less scarring.

Hair follicles

A hair follicle comprises a papilla, matrix, root sheath, hair fibre and bulge. Attached to the hair follicle is the arrector pili muscle which, when stimulated, allows the hair to stand perpendicular to the skin and protrude slightly to create goose bumps. Sebum and sweat are secreted by the sebaceous glands and apocrine glands onto the hair follicle for protection, lubrication, and pliability.

The colour of hair is due to the amount of melanin in the cells. Dark hair contains true melanin; blonde and red hair contain variants of melanin; and grey hair contains less melanin. White hair is due to air bubbles in the hair shaft and a lack of melanin.

Blood vessels

Arterioles, capillary networks and venules are found in the skin. The flow of blood is regulated by hormones and the nervous system. Blood vessels transport and distribute oxygen, nutrients and hormones and remove waste products.

Nerve fibres

Sensory and motor nerves are found in the dermis. Sensory nerve endings are sensitive to touch, or initiate signals that produce sensations of warmth, coolness, pain, pressure, vibration, tickling and itching. The sensory receptors are found throughout the skin and include tactile discs in the epidermis, corpuscles of touch in the dermis and hair root plexuses around hair follicles. Motor nerves aid the vasodilation and vasoconstriction of blood vessels and glands, and the contraction and relaxation of muscle tissues, ie the arrector pili.

Lymphatic vessels

The lymphatic system parallels the blood vessel supply and function. Permeability is greater than capillaries, so the lymphatic vessels frequently absorb proteins, lipids, and interstitial fluid when pressure is greater in the interstitial fluid (the fluid that surrounds cells of the body tissues) than in the lymph. The role of the lymphatic system is to transport lymphatic fluid, aid in circulating body fluids and help guard against disease-triggering agents.

Subcutaneous tissue

Adipose tissue (fat) lies under the dermis and helps the skin adhere to underlying structures.

Glands of the skin

There are many glands of the skin and each has its own function. Cerumen is the waxy substance that is secreted by the sebaceous glands in the external auditory canals. Sebaceous glands also secrete an oily substance, called sebum, that lubricates and softens the skin and hair and lessens water evaporation in low humidity. Sudoriferous glands produce perspiration regulated by the sympathetic nervous system.

Skin pigmentation

Pigmentation levels affect the colour of the skin that a human is born with: the three main pigments affecting skin colour are haemoglobin, carotene and melanin. People born with a golden skin tone, such as persons of Asian ancestry, have large amounts of carotene (a yellow-orange pigment) and melanin (a yellow-brown pigment). People born with brown or black skin have greater levels of melanin. Exposure over long periods of time can cause an accumulation of melanin, resulting in darkening or tanning of the skin. A pink skin tone is due to lack of melanin, which allows red blood cells carrying haemoglobin in the blood vessels of the skin to show through the almost translucent epidermis of Caucasians. Regardless of a person's racial origin, all scar tissue heals pink.

Common skin disorders

Skin infections and infestations

Minor skin infestations and infections are commonly seen in primary care (Schofield et al, 2011), including viral infections such as warts, herpes simplex, herpes zoster and COVID-19 skin manifestations. Many require no treatment for mild infections, however, in severe cases antiviral therapy and hospitalisation may be necessary.

Bacterial skin infections commonly seen in practice are Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and beta-haemolytic streptococci. The causative factors can be from a single pathogen or secondary infection, occurring in diseased or already traumatised skin. Common infections include folliculitis (inflammation and pustules at the hair follicle), furuncles (boils), carbuncles (a group of infected hair follicles), cellulitis (localised infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue) and erysipelas (infection of the upper layers of the skin). Treatments can vary from no treatment to the use of emollients, antibiotics and, in severe cases, hospitalisations. Patients who present with bacterial infections should be monitored carefully, noting the spread of inflammation and marking and measuring this clearly on a body map. Some bacterial skin infection such as erysipelas are a medical emergency and require urgent attention.

Fungal infections can cause superficial skin infections but are often diagnosed and treated only when patients access health care for other reasons (Nazarko, 2011). Caused by two main groups, dermatophytoses (tinea or ringworm) and candidiasis (yeasts), fungal infections are generally seen in patients who are already on antibiotics (which disturb the normal flora), have an underlying medical condition (such as diabetes mellitus, leukaemia or HIV), or are elderly, pregnant or obese. Areas of the body at risk of fungal infections include skin between the toes and under folds of skin. Local fungal infections are treated with topical antibiotics such as a creams or powder for 1 to 4 weeks. If the skin is particularly sore, red and painful, it can be treated with topical steroids in conjunction with the antibiotic treatment.

Skin disorders can also be a result of infestations, for example with lice, scabies, fleas and bedbugs. They can affect anyone but are often linked with crowded or unsanitary conditions. Management can include wet combing of hair, shaving of pubic hair, washing of clothes and bedlinen, the application of parasiticidal preparations to skin and hair, and general household cleanliness and care of animals.

Acne

Acne is a treatable and preventable skin disorder normally found on the face, back and chest. It occurs when there is partial or total obstruction of pilosebaceous ducts due to the hypercornification of cells. It is categorised as non-inflammatory and inflammatory. Non-inflammatory acne leads to the development of non-inflamed comedones and pseudocysts. Inflammatory acne leads to inflamed papules, pustules and nodules (Oakley et al, 2014). The most common forms are acne vulgaris and acne conglobate.

Management of acne includes washing twice daily with a mild cleanser or antiseptic wash and avoiding picking or scratching spots. If pustules are present, a ‘traffic light’ guide on their management indicates:

- Red pustules—don't squeeze

- Yellow—squeeze gently

- Green—go to the doctor.

The British National Formulary (Joint Formulary Committee, 2022) provides clinicians with guidance on the options for treating acne, including first-line treatments of prescription-only systemic antibacterials and topical therapy. Under specialist advice only, oral isotretinoin may be considered for patients with severe acne that is resistant to oral antibiotic-containing first-line treatments.

A rare form of acne that requires urgent referral is acne fulminans. This is a severe form of acne conglobata, which mostly affects males and presents with sudden onset of systemic symptoms such as inflammatory and ulcerated nodular acne on the chest and back, and is painful. The upper trunk may present with bleeding crusts. The patient may have a fever and complain of painful joints and generally feeling unwell. In some instances, the patient may have loss of appetite and weight, with an enlarged liver and spleen. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021) a same-day referral for urgent dermatological assessment is required.

Referral may be necessary for patients who present with persistent psychological distress or a mental health issues.

Rosacea

Persistent reddening or flushing of the skin, accompanied by visible superficial facial capillaries (telangiectasia) is classified as rosacea. Many mistake this skin disorder for excess consumption of alcohol. Rosacea commonly affects middle-aged and older women, aged 36 to 50 years, with fair skin. Its cause is unknown. There are various types: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous and ocular rosacea. Management is focused on keeping the skin cool, avoiding alcohol and spicy foods, and the application of light moisturisers and sunblock. Dermatology advice for other treatments and antibiotics may be necessary.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common non-infectious inflammatory skin disorder that presents with periods of exacerbation and remission (Ryan, 2008). Classic skin scales are observed due to rapid acceleration of epidermal cells and build-up of keratin. A purple or reddened appearance can accompany the scaly plaque due to increased blood flow to the thickened epidermis. The cause is unknown, yet genetic predisposition and triggers such as trauma, infection, stress, smoking, hormones, medication and sunlight are thought to be contributory. The psychological impact of psoriasis is significant, with the plaques serving as a constant reminder of the condition.

It can appear as a single or multiple lesion commonly affecting the elbows, knees and scalp. Presentation of psoriasis can be plaque, guttae, flexural, erythroderma, localised pustular and generalised pustular (affecting the whole skin). Management of the condition depends on its severity: topical agents for mild to moderate disease, phototherapy for moderate to severe disease and systemic treatments for severe disease. However, patients often receive a combination of treatments.

Eczema

Eczema, which affects one in nine people, is defined as an itchy, inflammatory skin disorder. There are many types of eczema, such as atopic eczema, irritant eczema, allergic contact eczema, food allergy, xerosis (dry skin), lichen simplex from repeated scratching, gravitational eczema, discoid eczema and seborrhoeic eczema. Signs and symptoms of eczema differ with age and can start as early as 4 months of age.

Management includes removing trigger factors, keeping nails short, avoiding scratching and regular use of emollients to moisturise the skin. Medication may include steroids to reduce inflammation, antibiotics to treat infection, and antihistamines for pruritis. Referral for immunomodulatory treatments, phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs may be required in significant cases (British Association of Dermatologists, 2009).

Skin cancers

Long-term exposure to the environment and sun can cause malignant skin lesions. The three main types are:

- Actinic keratosis (pre-malignant epidermal lesion)

- Non-melanoma skin cancer (basal cell and squamous cell)

- Melanoma.

Risk factors include having fair skin, lots of freckles and precursor moles, a family history, lower immunity and radiation treatment. Treatment for skin cancers depends on whether it has been diagnosed at an early, medium or advanced stage (Cancer Research UK, 2020). It can include topical creams, surgery (wide local excision), sentinel lymph-node biopsy or lymph node removal, with adjuvant treatment such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and biological therapy. In advanced stages, management may be limited to symptom control and palliative care.

Psychodermatology

It is well documented that people with skin disorders can suffer from stress, low self-esteem, social isolation, depression and even be at risk of taking their own life (Zaidi and Lanigan, 2010). Psychological illnesses such as depression, anxiety and stress can also trigger or exacerbate a skin disorder. Therefore, classification of disorders connecting the skin and the mind have been developed in the field of psychodermatology. There are four groups:

- Psychophysiological: emotional stress causing inflammatory skin reactions

- Primary psychiatric: self-induced injury of the skin (iatrogenic)

- Secondary psychiatric: emotional consequences such as anxiety, anger and depression developing as a result of an existing skin disease

- Cutaneous sensory disorders: patients with no apparent dermatological skin or medical condition presenting with disagreeable skin sensations, such as itching, soreness and pain, and negative sensory symptoms, such as numbness and hypoaesthesia.

Management includes psychological interventions such as relaxation, psychotropic medications and focused psychiatric care.

Assessment

A holistic assessment of the skin requires the collection of both subjective and objective data. This should include a detailed history of the patient's skin condition, a general assessment of the patient, an assessment of the patient's knowledge and a physical assessment (Lawton, 2001). The clinician should ascertain the following:

- When the person first noticed the skin disorder

- How long it has been present

- How often it occurs or recurs

- The characteristics of the skin disorder

- What route it has taken

- Whether it is affected by seasonal changes

- The severity of the skin disorder

- Any precipitating or predisposing factors, eg family history of the condition

- What relieves the disorder if at all (pharmacological and non-pharmacological)

- Any related symptoms.

Ask questions about the person's skin, hair, nails and assess their level of knowledge of the disorder, as further health promotion and education may be required.

A full medical history should record any previous skin problems, allergies, prior lesions or moles, to assess whether the skin disorder is linked to other illnesses with which the patient may present. Current and past medication information should be recorded, including current and previous treatments.

The impact of the skin disorder on activities of daily living and the presence and number of moles on the skin, and previous exposure to radiation (including X-rays), coal tar or petroleum-based products should also be ascertained as part of an assessment.

Examination of the skin

General assessment

The skin often reflects the health status, self-caring abilities and state of mind of the patient and the existence of support. A general assessment of the skin will therefore often provide the nurse with some detail.

Physical assessment

The physical examination should occur in an area with bright natural light and allow the gathering of clinical information, including the colour of the skin both in relation to race and to the skin disorder; skin texture and temperature; moisture; turgor and presence of oedema. During the assessment, remember that the patient may feel uncomfortable, so the nurse should provide reassurance.

Document any scars, missing fingers, toes and limbs and the presence of any open wounds. The skin tells a narrative about the patient, so assess the distribution, character and shape of any lesions, their site and location. Skin lesions should be palpated between the finger and thumb (unless widespread) to assess whether the lesion is soft, firm, hard, raised or irregular, and its texture. Then the lesion should be given a colour, ie pink, red, purple and mauve (due to blood); brown, black and blue (due to pigment); white (due to lack of blood or pigment); or yellow and orange (due to bilirubin levels).

Use the correct terminology when recording any lesions (a list of the terms commonly used can be found in Table 2 and Table 3). Correctly describe the type of lesion and its spatial relationship with other lesions on the body, for example solitary (a single lesion), satellite (a single lesion in close proximity to a larger group), grouped (a cluster of lesions), generalised (total body area), or localised (a limited area of involvement that is clearly defined).

Table 2. List of common primary lesions

| Name | Presentation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Macule | A flat circumscribed area of colour change: can be brown, red, white, or tan | Vitiligo |

| Papule | An elevated ‘spot’; palpable, firm, circumscribed, less than 5 mm in diameter | Scabies or bite from an insect |

| Nodule | Elevated, firm, circumscribed, palpable, larger than 5 mm in diameter | Erythema nodosum |

| Plaque | Elevated, flat-topped, firm, rough, superficial papule, greater than 2 cm in diameter. Papules can coalesce to form plaques | Psoriasis |

| Wheal | Elevated, irregular area of cutaneous oedema: red, pale pink or white | Urticaria |

| Vesicle | Elevated, circumscribed, superficial, fluid-filled blister, less than 5 mm in diameter | Herpes simplex |

| Bulla | Vesicle greater than 5 mm in diameter | Bullous pemphigoid |

| Pustule | Elevated, superficial, similar to vesicle but filled with pus | Impetigo |

Table 3. List of common secondary lesions

| Name | Presentation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Thickened, flaky exfoliation, irregular, thick or thin, dry or oily, variable size, silver, white or tan in colour | Psoriasis |

| Crust | Dried serum, blood or purulent exudate; slightly elevated; size variable | Impetigo discoid |

| Excoriation | Loss of epidermis caused by scratching | Atopic eczema |

| Lichenification | Rough thickened epidermis, accentuated skin markings due to scratching | Lichen simplex |

Measure and photograph the lesions using rulers, grids or tape measures. Follow the organisation's policy on consent for medical photography and digital imagery.

Skin disorders present differently in patients with darkly pigmented skin, ie there are differences in skin colour, pigmentation and reaction patterns (Lang, 2000). Lesions that appear red or brown on light skin often present as black or purple on dark skin. Assess an area of skin that is not affected by the skin disorder and compare that with the area that has the skin disorder, drawing attention in the notes to any abnormalities. Be aware that mild inflammatory reactions may not be visible, so use touch to detect heat on an area of skin and note hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation, which may be a consequence of prolonged inflammation. Record reaction patterns such as follicular (affecting hair follicles), papular (elevations of the skin) and annular (ring-like skin conditions), as well as keloid scarring.

Also remember to assess the degree of discomfort the patient may be experiencing from itching, pain and soreness from the condition. Identification of the underlying cause assists with appropriate management and treatment.

Case study

A 22-year-old patient presented to the GP with dry cracked hands with areas of inflammation and symptoms of itching, especially at night when sleeping (Figure 2). He had been following advice from Public Health England on preventing the spread of COVID-19 to wash his hands frequently and to use alcohol-based hand sanitiser gels. This was now causing him pain and affecting his sleep and personal hygiene and leading to embarrassment at work. The patient had tried some aqueous cream to no effect. He also reported being allergic to animal fur and feathers.

Reflection

- What skin disorder do you think the patient would be diagnosed with?

- What treatments might be prescribed?

- How might you record the skin assessment in his notes?

- What health promotion advice might you give to the patient about hand care?

Conclusion

Nurses play an important role in ensuring patients with skin disorders receive efficient and safe patient care. Competence in managing the care of patients who present with skin disorders includes knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the skin and awareness of the common skin disorders and how they present on examination. During an assessment of a patient with a skin disorder a holistic skin assessment should be conducted, ensuring privacy, dignity and reassurance as the assessment may be embarrassing. A detailed history of the patient's skin condition, a general assessment of the patient, an assessment of the patient's knowledge and a physical assessment should be carried out and documented using the correct terminology for the type of skin disorder and lesions the patient presents with. Management can include topical creams, emollients, and antibiotics as well as other therapies. Although most skin disorders are mild some can require urgent medical assistance due to the severity.

KEY POINTS

- Most skin disorders are self-managed

- Holistic assessment of the patient is essential to aid diagnosis, treatment and to evaluate the impact on activities of daily living

- Some skin disorders are classed as a medical emergency