Pain is one of the most common patient problems that health professionals will encounter. It is universally experienced and extremely complex, involving the mind as well as the body, and activated by a variety of stimuli, including biological, physical and psychological (Cook et al, 2020).

For some patients, the pain they experience can be short lived and easy to treat, but for others it can cause significant issues to their overall health and wellbeing (Flasar and Perry, 2021). According to Mears (2018), mismanaged pain can affect an individual's mobility, sleep pattern, nutritional and hydration status, and can increase the risk of developing depression or becoming socially withdrawn. This article, therefore, examines and explores some of the holistic nursing assessment and management strategies that can be used by health professionals.

Pain theories

Knowledge of pain processes has changed considerably over the past 500 years, when there was the belief that pain is a sensation linked to body fluid imbalance, evil spirits or a punishment from God (Ford, 2020). In 1965, Melzack and Wall conceptualised and pioneered a new model of pain, referred to as the ‘gate control theory’. They hypothesised that neurons within the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord could modulate the flow of signals from the stimulation of peripheral nociceptors (sensory neurons) through the central nervous system to the brain, thus effectively increasing or decreasing the amount of pain experienced (Todd, 2016). They further postulated that the gate control was influenced by psychological and physiological factors and, accordingly, have been credited with taking the first step in recognising the symbiotic relationship and the interactive, interdependent nature of these factors.

This psychophysiological theory and its underlying principles have widespread applicability and have consequently laid the foundation for some of the additional altered models that have been developed over the past 50 years (VanMeter and Hubert, 2022).

One such model is Engel's ‘biopsychosocial model’, which has taken the gate theory one step further, reinforcing the uniqueness of individuals' pain experiences. It reaffirms that pain often results from the culmination of a myriad of factors that are biological, social and psychological in origin (Engel, 1980). These can include stimulus intensity, genetic predisposition, economic and environmental factors, cultural beliefs, and individual pain perception and coping mechanisms (Ford, 2020). Melzack has also advanced and extended the gate control theory of pain, in order to address the original theory's inability to explain phantom limb pain (Keefe et al, 1996). This has resulted in the creation of the ‘neuromatrix’ theory of pain, and a greater understanding of the role of supraspinal influences and brain function on pain perceptions (Keefe et al, 1996). This supplementary theory proposes that the multidimensional experience of an individual's pain is a result of a unique neurosignature (nerve impulse pattern in the brain), which can be caused by genetic and sensory influences, triggered by sensory stimuli and also when stimuli are absent (Melzack, 2001; Melzack, 2005; Melzack and Katz, 2013).

Pain pathways

Pain pathways are associated with ascending, descending and modulating processes (Figure 1) and, although some treatments and management approaches are effective in interfering with the signals being sent to the brain, others could play a role in how the body responds to these signals after they are received and interpreted by the brain.

The first part of the pathway is usually associated with the stimulation of sensory nerve endings, or ‘nociceptors’, by chemicals such as histamine and prostaglandins, which are released when tissue injury or irritation occurs (Boyd, 2022). Nociceptors are specialised peripheral nervous tissue that are sensitive to changes in the environment and, more importantly, to thermal, mechanical and chemical noxious stimuli. Once activated, these primary sensory neurons carry impulses via afferent A-delta (q) fibres (wide, myelinated, fast and associated with localised sharp pain) and C fibres (narrow, non-myelinated and slower) towards the central nervous system (CNS) (Todd, 2016). Both A and C fibres terminate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord forming synapses, where the action of neurotransmitters (ie glutamate and substance-P) continues to transfer the signals along relay neurons to the somatosensory cortex (Ashelford et al, 2019).

The perception of pain signals in the brain can be influenced by an array of factors, which can psychological, physical, social and pharmacological in nature, and the response to the perceived pain signals could be in the form of emotional reactions and physiological responses, activating the descending inhibitory efferent pathways. Signals are transmitted from the brain, back to the dorsal horn, where nerve endings are activated to release neurotransmitters (noradrenaline, serotonin and endorphins) which bind to the afferent pain fibres, inhibiting the synaptic transmission to the relay neurons.

It is in the descending pain pathway that opioids have been recognised as being the most effective medication, by inhibiting the synaptic transmission between the pain fibres. However, the way in which this occurs is different from the body's natural inhibitory mechanism. Opioid peptides, once these have bound to the appropriate receptors – mu (µ), kappa (k) and delta (q) – modulate pain input in two ways. They release a large number of calcium ions, which block the presynaptic terminal and also open potassium channels, which flood the synapse and hyperpolarise the neurons, preventing signals from passing across the synapse (Bannister, 2019).

Classifications of pain

Before looking at the assessment process, it is necessary to provide some background information on the various types of pain that can be experienced, as well as how these are manifested, who is at greater risk and what barriers health professionals need to overcome (Cunningham, 2016). Being in possession of this information not only serves to improve knowledge levels, but also ultimately helps inform management decisions – as Cook et al (2020) stated, it is the first step in the assessment process.

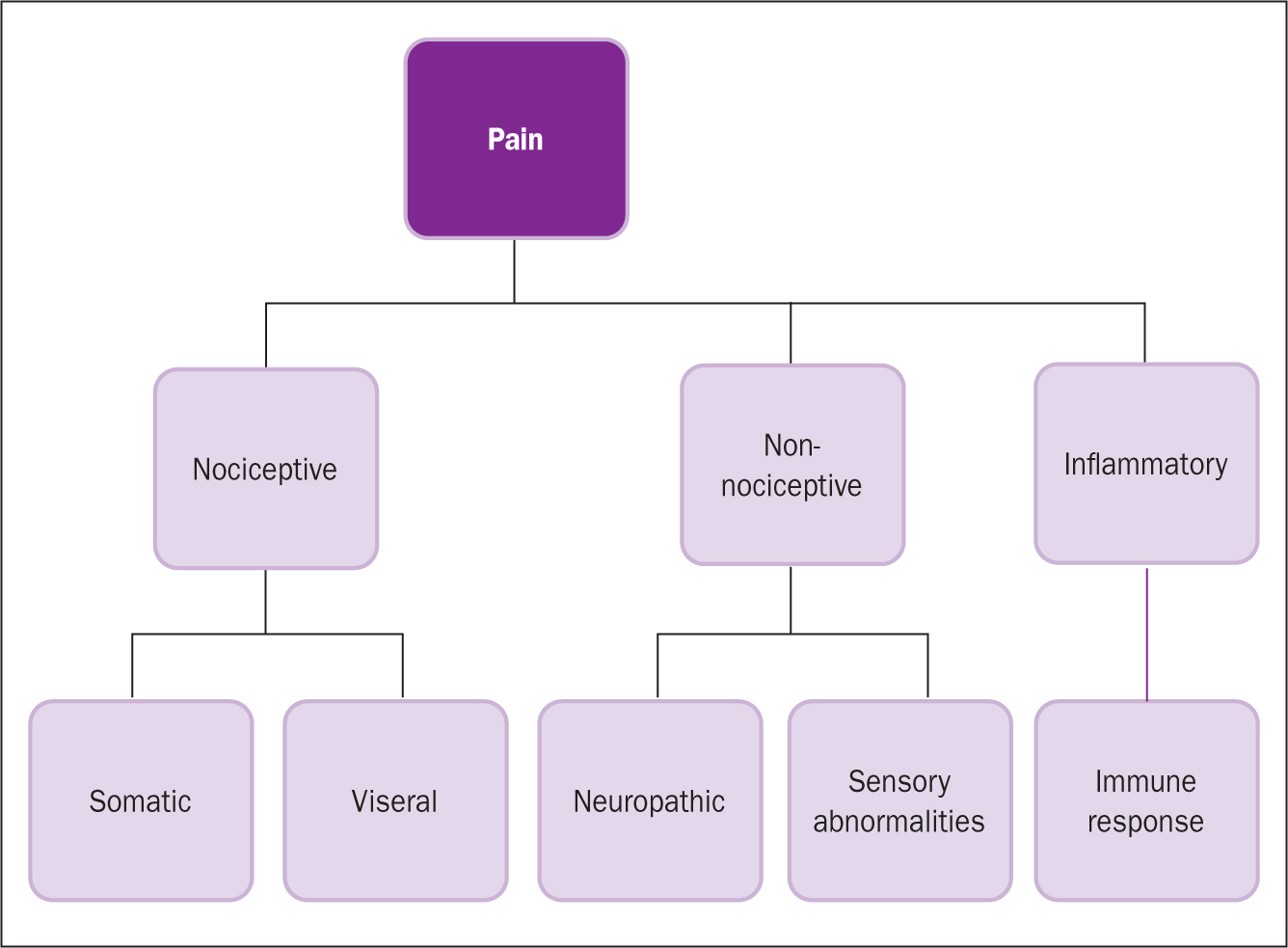

There are several classifications of pain (Figure 2), some of which overlap, and patients may present with one or more type (Colvin and Carty, 2012; Laws and Rudall, 2013; Cunningham, 2016; Mears, 2018; Kettyle, 2022; Cook et al, 2020).

- Acute: serves a protective purpose. It is of short duration (less than 3 months) and is reversible. It is predominantly nociceptive in nature, involves sensory processes and is treated very effectively with analgesics. Examples of acute pain include pain associated with surgical procedures, fractures and dental work, minor injuries, and burns

- Chronic: serves no protective purpose and persists past the initial healing stage, usually more than 3 months. It is largely neuropathic, associated with an array of changes to the peripheral and central sensory pathways, typically connected with chronic disease. It is usually treated alongside psychological measures due to its extremely subjective nature. Examples of chronic pain include pain associated with conditions such as arthritis, fibromyalgia, cancer, and nerve and spinal injury

- Nociceptive: the most frequently experienced type of pain. It is a primitive sensation, protective in nature, and involves the passing of information through primary afferent fibres to the cerebral cortex via pain receptors, referred to as nociceptors; these are stimulated and activated by tissue damage resulting from heat, cold, stretch, vibration or chemicals (Mears, 2018).

- Neuropathic: more degenerative in nature and usually occurs as a result of pain related to sensory abnormalities that can result from damage to the nerves (a nerve infection) or neurological dysfunction (a disease in the somatosensory nervous system). This type of pain may not be diagnosed immediately, as it can manifest itself in various ways and can often be confused with acute persistent pain. Neuropathic pain is often managed via multimodal analgesic approaches (Colvin and Carty, 2012)

- Inflammation: stimulation of nociceptive processes by chemicals released as part of the inflammatory process (Cunningham, 2016)

- Somatic: a large part of the body's natural defence mechanism that is associated with nociceptive processes activated in skin, bones, joints, connective tissues and muscles (VanMeter and Hubert, 2014)

- Visceral: this is a sensation and nociceptive process activated in the organs (ie stomach, kidneys, gallbladder), transmitted via the sympathetic fibres and linked to conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and dysmenorrhoea (Cook et al, 2020)

- Referred: pain that is felt in the skin that lies over an affected organ, or in an area some distance from the site of disease or injury. Examples of referred pain include the experience of dental-related pain during a myocardial infarction.

Assessment

Individuals react to pain in varying ways: for some it will be something that should be endured, while for others it can be a debilitating problem that detrimentally influences their ability to function. Therefore, in order to ensure the development of an effective and individually tailored holistic management plan, it is important to understand how the pain is uniquely affecting the individual from a biopsychosocial perspective (Flasar and Perry, 2021). To do this, health professionals use a range of tools, such as the skills of observation (the art of noticing), questioning techniques, active listening, measurement and interpretation. No single skill is superior – rather, it is the culmination of information gathered via the various methods, which enables a health professional to determine whether a patient is in pain, and how this pain is affecting them physically, psychologically, socially and culturally (Cunningham, 2016) (Table 1).

Table 1. Example of assessment domains

| Physical appearance | Physical impact |

|---|---|

|

|

| Pain characteristics | Emotional/behaviour |

|

|

| Quality of life | Past experiences |

|

|

One of the first skills that can be applied is to visually observe the patient, and to note especially their body language, facial expressions, and behaviours, as these are cues that provide information about how a person is feeling. For example, an individual in pain may be quiet, withdrawn or very vocal, angry and irritable. They may display facial grimacing and teeth clenching, or exhibit negative body language, an altered gait and guarding. Within healthcare, the latter are behaviours that some individuals may demonstrate to prevent, alleviate or minimise pain. These behaviours include holding the area, bracing before movement or hesitation, for example, upon palpation of their abdomen, the patient stiffens and holds their breath when the health professional touches them.

However, there may be times when an individual may not be able to exhibit behavioural signs of pain, such as when they are unconscious. Therefore, physiological responses to noxious stimuli can be observed through the measurement of vital observations, such as hypertension, tachycardia and tachypnoea. Although these observations are routinely used within perioperative and critical care areas, they can also be present in the absence of pain. Consequently, these observations must be used in conjunction with other assessment strategies (Laws and Rudall, 2013).

Assessment tools

Vital observation and behaviour manifestations may indicate that a patient is in pain. To determine the intensity, severity, and effect of the pain on a patient's wellbeing and quality of life nurses can apply their measurement and interpretation skills. The process can be aided with the use of specifically designed tools, which act as prompts for health professionals and facilitate the assessment of one or more dimensions.

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Verbal Rating Scale (VRS): these can be quick and easy to use, can be regularly repeated and do not require complex language. They are limited in terms of the information gained, since examining a single specific aspect is not sufficient for adequate and holistic pain management (Mears, 2018). However, for individuals who are unable to communicate or where there is a language barriers, unidimensional tools such as Wong-Baker FACES, can be useful (Kettyle, 2022)

- Multidimensional tools: these ask for greater information and measure the quality of pain via affective, evaluative and sensory means. The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) is one example, but it can be complex and the language used may not always be appropriate for individuals with cognitive impairments. However, many other multidimensional tools are available, such as the Abbey Pain Scale (APS) that has been designed with these specific patients in mind

- Mnemonics: OPQRST–onset, provocation, quality, radiation, severity and time, and SOCRATES – site, onset, character, radiation, associated features, time course, exacerbating or alleviating factors, and severity are just two examples of mnemonic aids, which can be useful and require no equipment because they use mental assessment processes only.

However, regardless of which tool is used, pain assessment will not be successful if the health professional fails to use the tools appropriately, ie using the wrong tool for the wrong patient.

Management strategies

The primary goal for all patients is to pre-empt and prevent pain from occurring in the first instance. However, if pain cannot be avoided, optimal analgesic management is vital. The word analgesia ‘to be without feeling of pain’ is derived from the Greek language, and in terms of pain management can relate to medication and alternative interventions (Law and Rudall, 2013). Therefore, pain management plans should incorporate a multimodal approach in order to successfully and holistically treat patients' pain (Flasar and Perry, 2021).

Cook et al (2020) agree that this is an effective way to manage pain, but state that the decisions about which management strategies to use also need to take into consideration the context of the clinical situation, the patient's level of acuity, the environment and physical space, and the availability of resources.

Pharmacological

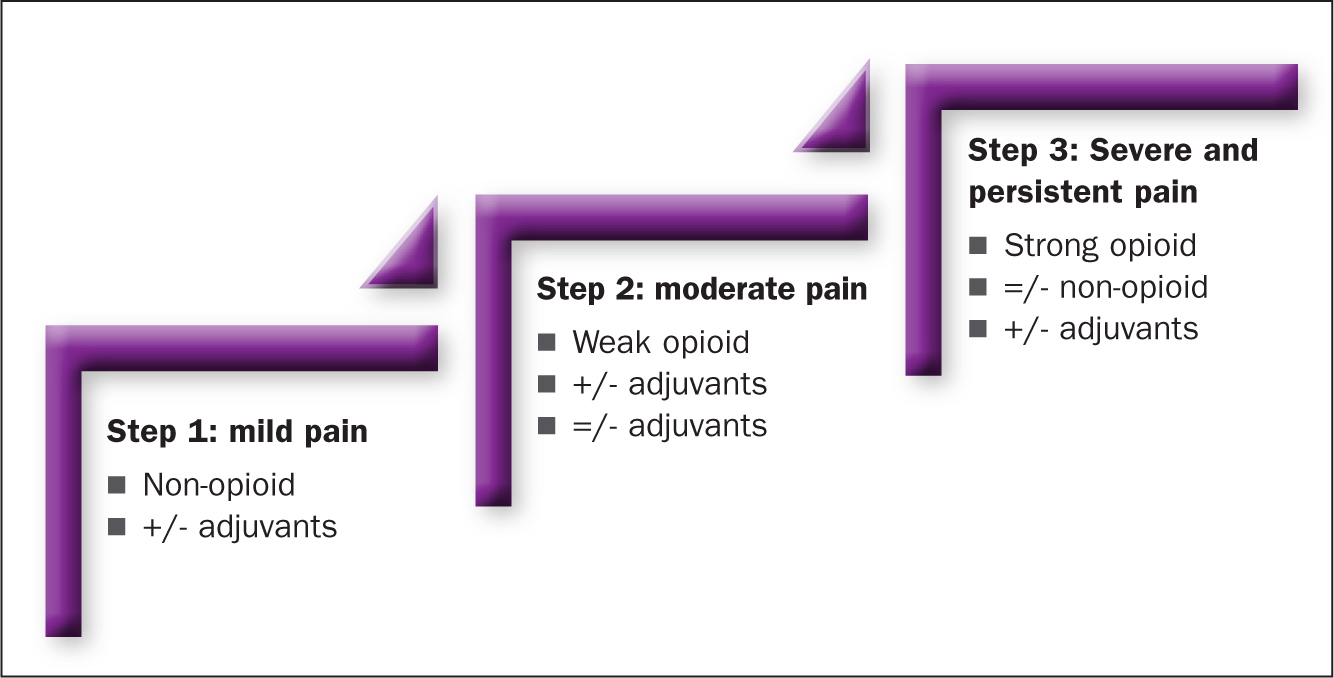

One very effective strategy that health professionals have within their management arsenal is the use of pharmacological treatments. As patients may respond differently to various medications, there is no one-size-fits-all answer to pain management. Therefore, the choice and combination of drugs should be tailored to the individual patient's needs, taking into account factors such as the type and severity of pain, potential drug interactions, risk of adverse effects and patient preferences (see Figure 3). Combining medications from different categories (see Table 2) can often achieve enhanced analgesic effects, so multimodal analgesia approaches can also be utilised.

Table 2. Classifications of pharmacological analgesics (examples)

| Non-opioids/NSAIDs | Opioids | Adjuvants/co-analgesics |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

There are three main categories of analgesics (Table 2):

- Non-opioids/non-steroidal anti-inflammatories

- Opioids

- Adjuvants/co-analgesics.

Examples of how these can be combined within a multimodal approach include, but are not limited to, the following:

Acute pain

This can be treated with a range of pharmacological analgesics depending on the level of severity. For example, low levels of pain from a surgical procedure can be treated with paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID); mild pain can be treated with paracetamol and/or NSAIDs with the addition of mild opioids such as codeine; for more severe levels of pain, paracetamol and/or NSAIDS can be administered along with stronger opioids such as morphine.

Chronic pain

This can also be treated with a variety of pharmacological analgesics, usually commencing with non-opioid analgesics for mild pain, with the additional introduction of antidepressants with analgesic properties, such as amitriptyline, for pain that is less well managed. If the chronic pain experienced has a neuropathic component, then gabapentinoids can also be introduced. If all other strategies prove to be ineffective, then opioids may be considered.

Non-pharmacological

Pharmacological treatments are not the only strategy at a health professional's disposal, and true holistic management cannot be achieved without incorporating non-pharmacological therapies. Some of these interventions are long standing and are engrained in the traditional medical practices of some countries; when used correctly, they can enhance patients' feelings of empowerment and involvement (Flasar and Perry, 2021). However, due to limited resources, funding, space, time, knowledge of use and personal beliefs, some therapies are not fully used or embraced (Cullen and MacPherson, 2012).

These can be placed into three main groups (Table 3), the choice of which to use will depend on patients' preferences and existing coping mechanisms. The following strategies have been highlighted because they align with the fundamental core values of care and compassion and require very little in terms of resources or time.

Table 3. Example non-pharmacological management strategies

| Psychological/emotional | Physical | Alternative |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Distraction

This method, while simple, is often a very effective non-pharmacological analgesic technique: it normally involves engaging individuals in conversations about their hobbies or interests, to divert attention away from the immediate pain they are or will experience. It is extremely cost-effective because it requires no special equipment, is versatile and accessible, and can complement other pain management techniques. However, its effectiveness may vary depending on the patient's past histories and experiences, and it only provides temporary relief.

Imagery/meditation

This technique for pain management goes beyond distraction therapy by incorporating visualisation, mindfulness and relaxation techniques in a structured and integrated approach. It is non-invasive and versatile and, when used as part of a comprehensive pain management approach, it can be a valuable tool for improving wellbeing and quality of life. However, it also has limitations, particularly in terms of the additional skills health professionals will need to acquire, and there is wide variance in its effectiveness.

Therapeutic touch and massage

For centuries, the therapeutic placing of hands has proven to be a useful skill that has beneficial physiological and psychological effects, as they stimulate A-beta fibres, which can block pain signals, reduce discomfort, induce relaxation responses, and reduce muscle tension and lower heart rates (Kettyle, 2022). More importantly, these techniques, which involve the health professional touching a patient, foster an increased sense of connection and intimacy, promoting a therapeutic link that can improve patients' mode and overall psychological wellbeing.

Environment

Sound, lighting and the temperature of a patient's immediate environment have been shown to heighten or reduce an individual's perceptions of pain. Soothing sounds and dim lighting can promote relaxation and reduce pain, while loud noises and bright lights can increase stress and intensify pain. Moderate temperatures also tend to be more comfortable and can alleviate muscle tension, potentially easing the sensation of pain. However, extreme temperatures can exacerbate discomfort and increase pain perception, ie extreme cold may cause stiffness and heightened sensitivity, while excessive heat can lead to sweating and aggravate inflammation.

Body positioning and comfort

This can be used to help patients cope with the pain levels they are experiencing and, in some instances, can reduce the pain associated with nociceptive and inflammatory pain signals. For example, paying particular attention to an individual's body position can redistribute weight and alleviate pressure on sensitive areas; promoting patient comfort can also aid in relaxation and promote a sense of wellbeing. Additionally, body positioning techniques, such as adjusting the position of a patient with lower back pain to reduce strain on the affected area, may complement pharmacological interventions by enhancing their efficacy.

Thermoregulation

Hot and cold packs can help reduce pain. Heat therapy improves circulation, relaxes muscles and soothes damaged tissue. However, it should not be used where there is an open wound or when there are pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes or deep-vein thrombosis. Cold therapy reduces inflammation and swelling, and relieves pain, but it is not recommended for people with sensory disorders or poor circulation.

Electrostimulation

This technique is non-invasive and uses pulsed electrical currents to stimulate A-beta fibres, which inhibit the transmission of nociceptive signals in the pain pathway (Johnson, 2012). The electrical current is normally transmitted transcutaneously: electrodes are attached to the skin and can be easily positioned and removed. This technique is relatively inexpensive, easy to use and, for most people, has no side-effects – it can help reduce pain and muscle spasms associated with conditions such as arthritis, dysmenorrhoea and musculoskeletal injuries. This treatment is contraindicated for individuals with pacemakers or any other type of electrical or metal implant and should not be utilised for patients with a history of seizures or heart conditions.

Conclusion

This article has focused on providing a deeper understanding of the physiology of pain and the various classifications used within clinical practice, and highlighted the skills required to assess and manage an individual's pain

It has explored the tools used to assist with the assessment of pain and introduced some of the management strategies that can be used to manage pain. It has also examined some of the barriers to effective pain assessment and management.

KEY POINTS

- A sound understanding of the pathophysiology of pain is essential when caring for individuals in pain, enabling health professionals to recognise how and when pain can negatively impact health, wellbeing and recovery from illness

- When choosing a pain assessment tool to assess pain, health professionals must take a biopsychosocial approach and be aware of context

- It is essential to include individuals in their own care, as decisions about how pain management must be tailored to individual need

- When assessing pain, health professionals need to consider that it could be related to a serious underlying health condition or a complication. It is therefore important to liaise with other health professionals to ensure the underlying cause is investigated and the pain managed safely and effectively

CPD reflective questions

- How has your understanding of pain assessment and management evolved over the past year, and how have these changes influenced your clinical practice?

- Can you identify any biases or preconceptions you may hold regarding pain assessment and management in adults, and how do these impact the care you provide? What steps could you take to mitigate these biases?

- Reflect on a recent patient case where pain assessment and management were particularly challenging. What strategies did you employ, and what lessons did you learn from that experience to improve your future practice?

- How do you stay up to date with the latest evidence-based practices in pain assessment and management? What resources and professional development opportunities can you engage with to ensure you are providing the best care for individuals experiencing pain?