In Europe 4 million people a year will develop a healthcare-associated infection (HAI), of whom 37 000 will die as a direct result (Public Health England (PHE), 2016). A urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common of these infections and in the UK accounts for 19% of all HAIs. The major risk factor for developing a UTI is having a urethral catheter in situ and between 43% and 56% of UTIs are associated with having a catheter (Loveday et al, 2014). Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) has major implications both for patient safety and for the costs of healthcare delivery (Oman et al, 2012). As nurses provide the majority of catheter care it is important to be aware of how and why CAUTI occurs, identify those at risk of CAUTI, signs and symptoms of CAUTI and prevention strategies.

CAUTIs have significant associated costs to the health service (additional bed days and treatment costs) that are estimated at £99 million per annum and £1968 per episode, therefore infection prevention is vital (Ward et al, 2010). The main risk factor for developing a CAUTI is having a catheter in situ. Catheter avoidance is advised; however, this is not always possible. Patients may have to have a urethral catheter inserted for several reasons (see Box 1).

According to the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2012) guidelines some patients are at greater risk of developing a CAUTI. These include:

The indication for catheterisation should always be documented and this should be updated every 24 hours. Catheterised patients should be monitored closely for signs of CAUTI.

Signs and symptoms of CAUTI

Common signs and symptoms of CAUTI include urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, pelvic/lower abdominal pain, pyrexia and tachycardia. In elderly people symptoms may be more complicated to detect as the ageing immune system is less likely to produce a proper response to infection (Robichaud and Blondeau, 2008; Hooton et al, 2010). Change in behaviour in the form of agitation, confusion/delirium, dizziness, falls (new onset) and loss of appetite may all be indications of CAUTI in elderly people (Bardsley, 2017). More localised problems such as catheter obstruction, blood in the urine, foul-smelling or discoloured/cloudy urine (Figure 1), can also be indications of active infection (Nicolle, 2014).

How CAUTIs develop

Following catheter insertion, bacteria appear in the urine within 24-48 hours and the risk of developing a CAUTI increases the longer the catheter remains in place (Aaronson et al, 2011; Nicolle, 2014). A CAUTI is most commonly caused by Escherichia coli (E. coli). See Box 2 for other common bacteria responsible for UTIs.

Bacteriuria occurs when biofilm forms on the surface of the catheter. Biofilm is a complex organic material that begins to form immediately after catheter insertion. Organisms adhere to both the interior and exterior catheter surface. This provides a physical barrier that antibiotics are unable to penetrate, therefore allowing these organisms to multiply. This increases infection risk (Bardsley, 2017). Catheterised patients can continue to acquire new organisms at a rate of 3-7% per day (Nicolle, 2014).

Bacteria can enter the urinary tract from the patient via the periurethral area by migrating from the catheter tubing into the bladder (endogenous infection) or through cross-contamination via the hands of healthcare staff at catheterisation or when handling the catheter tubing or bag (exogenous infection).

Patients with CAUTI can act as reservoirs of infection, putting other patients at risk by increasing the potential for cross-contamination (Gould et al, 2009). Gram-negative bacteria, the main cause of UTI, are becoming more resistant to antimicrobial therapy and this is a serious concern in acute hospital and community settings (Pallett and Hand, 2010). For this reason, only symptomatic patients should be treated with antibiotics.

Diagnosing CAUTI

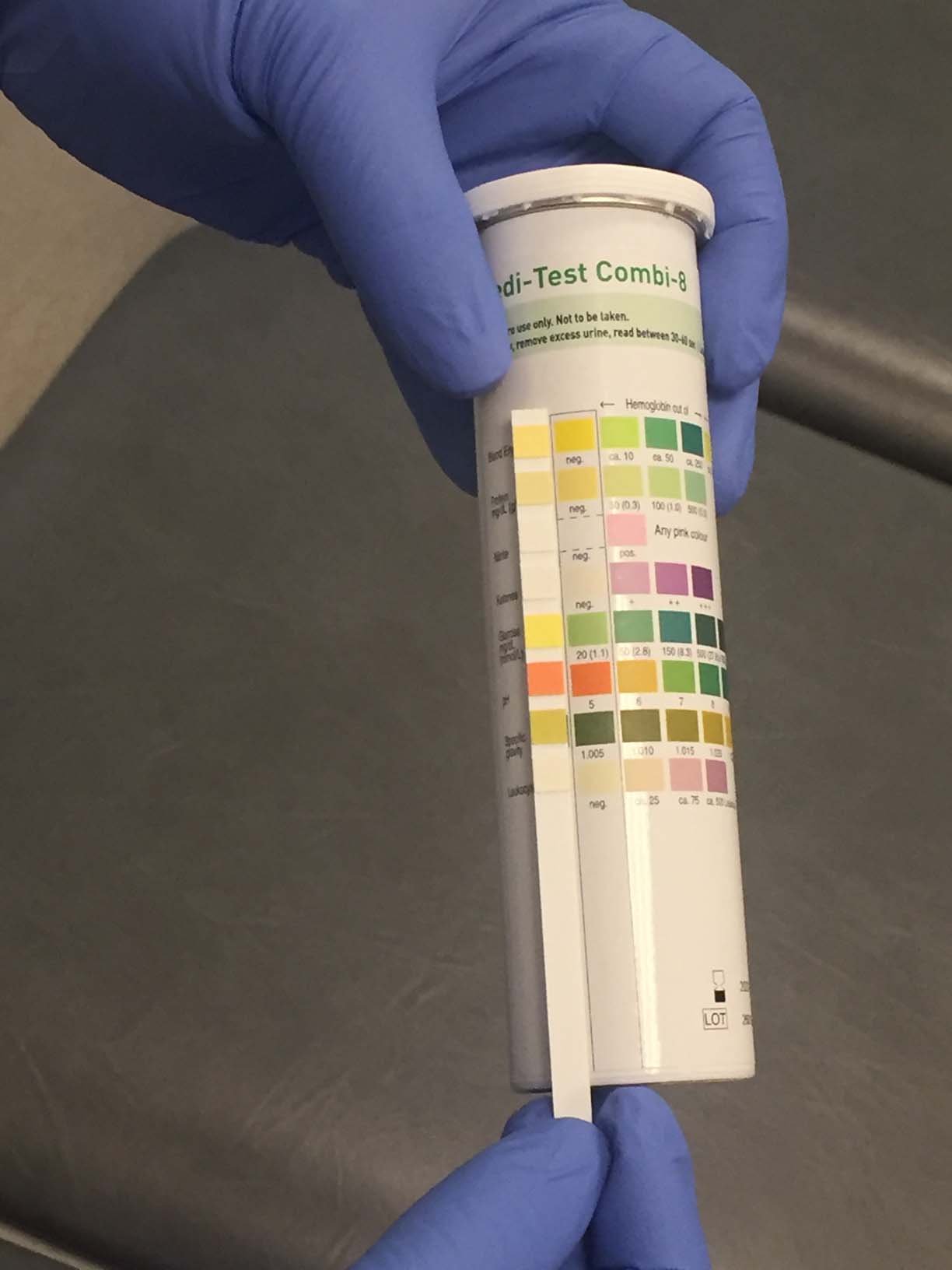

Urinalysis (Figure 2) is a simple test that can be performed by nursing staff at the bedside to help diagnose a CAUTI. However, this should not be used in isolation for diagnosis and patient symptoms should always be taken into account (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), 2012). Presence of leukocytes (white blood cells) and nitrites are the main indicators of ongoing infection. Leukocyte esterase is part of the body's natural response to infection, while nitrites are only present in urine as a result of the bacteria feeding on the nitrogen waste in the urine (Mundt and Shanahan, 2016). If infection is suspected a urine sample should be sent to the laboratory for microscopy, culture and sensitivities.

Due to the high possibility of colonisation of bacteria, a specimen should never be obtained from the catheter bag but taken aseptically from the needle-free sample port. For patients who have had a catheter in situ for 7 days, best practice recommends changing the catheter and obtaining the sample from the new catheter as the microorganisms may have adhered to the wall of the previous catheter and may not be indicative of microorganisms present in the bladder (RCN, 2012; SIGN, 2012; Loveday et al, 2014; PHE, 2016).

Preventing CAUTI

Guidance

It is important for nurses to keep up to date with best practice. This is a requirement set out in the Code (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018). Currently in the UK, the RCN (2012) guidelines and the epic3 guidelines (Loveday et al, 2014) cover how to prevent CAUTIs. This guidance is based on systematic reviews of the available scientific literature and the consensus opinion of relevant experts in the field and is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Gould, 2015). Following the available guidance helps ensure patients receive safe, high-quality care.

Guidance indicates that indwelling catheters should only be used where no suitable alternative exists and should be removed as soon as possible (RCN, 2012; Loveday et al, 2014). Maintaining accurate clinical records helps nurses to establish the clinical indication for catheterisation and helps guide the decision to remove a catheter.

Infection control

Catheterisation should always be performed using an aseptic technique and sterile equipment. The most appropriate style, gauge and length of catheter should be chosen on an individual patient basis and only those who have been deemed competent in this skill should be inserting catheters.

Personal protective equipment such as gloves and aprons should be used when providing catheter care. Local infection control guidance should always be followed. Maintaining a sterile, continuously closed urinary drainage system is central to the prevention of CAUTI (Loveday et al, 2014). The drainage bag should only be changed in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines but this is usually every 7 days. If patients use leg bags these should remain in situ and the night bag should be attached to this to avoid opening the closed system.

Treatment

Owing to the ongoing and ever-increasing problem of antimicrobial resistance, only patients with CAUTI who are symptomatic should be treated with antibiotics. Before commencing an antibiotic, the catheter should be changed. Antibiotics should be chosen based on sensitivities picked up on urine cultures and should be in line with local guidelines (Kelly-Fatemi, 2015). SIGN (2012) recommends a 7-day course of antibiotics for patients with CAUTI where symptoms are promptly resolved. For those where the response is delayed (5 days) a 10-day treatment course is advised. This decision should be made by the prescriber.

Conclusion

Responsibility for preventing CAUTI lies with all health professionals. However, as nurses provide the majority of catheter care they should be champions of good practice. Nurses should perform catheterisation only when there is no suitable alternative and catheters should be removed as soon as clinically acceptable. Following available guidelines can significantly reduce the incidence of CAUTI. This will have substantial benefits for patients but also to the NHS as a whole.