Children and young people in care are a vulnerable group in society, and are known to have poorer health and educational outcomes compared with their peers. It is important that nurses understand the personal and social background of this population to ensure that appropriate assessment and support can be provided. By appreciating the context of this group, nursing care can be improved; however, individualised input remains vital.

Definitions

There are several terms used to identify children and young people who are, or have experience of being, in care. In England, the term used in clinical practice is ‘looked after child’ abbreviated to LAC, based on the underpinning legislation—the Children Act 1989. When asked, children and young people themselves state that they prefer the term ‘children in care’ (National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, 2019). This is because the term ‘looked after’ suggests that they were not looked after in their previous setting, which many children and young people find a distressing implication.

Under the Children Act 1989, a child is ‘looked after’ by a local authority if they fall into one of the following categories:

Voluntary entry into care

If a local authority considers that providing accommodation for a child would safeguard that individual or benefit their welfare, the authority may seek a voluntary agreement under section 20 of the Children Act 1989. In the case of a child aged under 16 years this requires the consent of those with parental responsibility, and if the young person is aged over 16 years, he/she must consent Section 20 of the Children Act 1989 may be used if there is no person with parental responsibility for the child, the child is lost or abandoned, or the person who has been providing care is prevented from providing suitable accommodation or care.

Care order

Under the section 31 of the Children Act 1989 a care order is defined as an order made by a court to place a child in the care of a designated local authority or under the supervision of a designated local authority.

According to data collected in 2018, 73% of ‘looked after’ children were recorded as being under a care order (Department for Education (DfE), 2018). The data also indicate that the proportion of children in this category continues to rise because the number of those under a voluntary arrangement continues to decrease (DfE, 2018).

Placement order

Section 21 of the Children Act 1989 is a placement order that provides a local authority with the legal status to place a child for adoption.

Who are children in care?

Local authorities in England collect and submit data annually regarding children in care (this data collection is also known as SSDA903). The data for 2019 have not yet been published, so the latest figures available are those released for 2018 (DfE, 2018).

In March 2018, there were 75 420 children in care throughout England, up 4% from the previous year. This continues to follow an increasing trend identified within the data. Both the number of children commencing a period in care and the number of those leaving the care system decreased, down 3% and 5%, respectively. The average duration of the most recent period in care was 772 days.

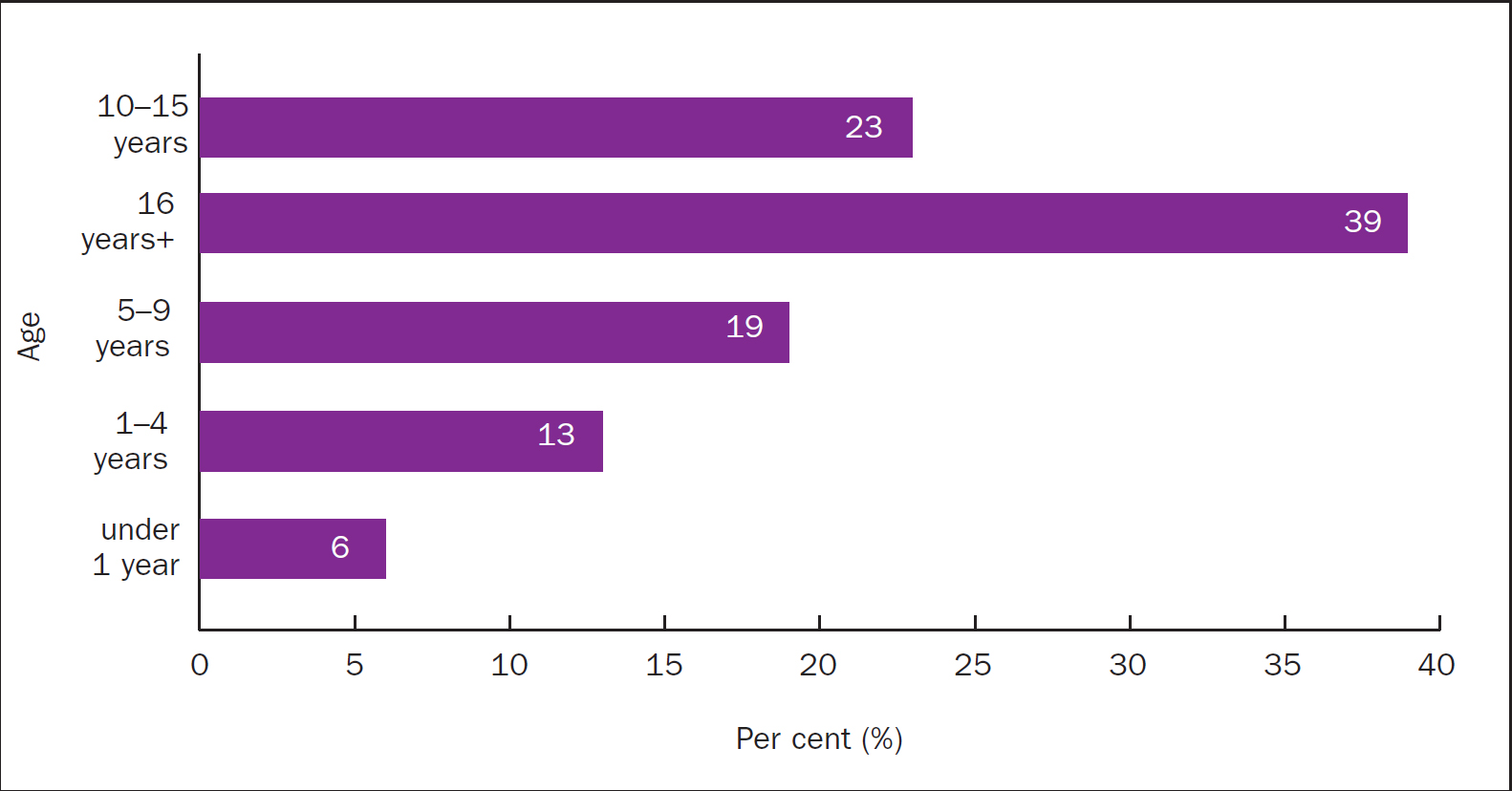

Data show that the characteristics of children in care tend to remain stable: 56% are male and 44% are female; the ethnic background of the majority (75%) is white, 9% mixed and 7% black (DfE, 2018). Figure 1 shows the percentage of children in different age groups who are in care.

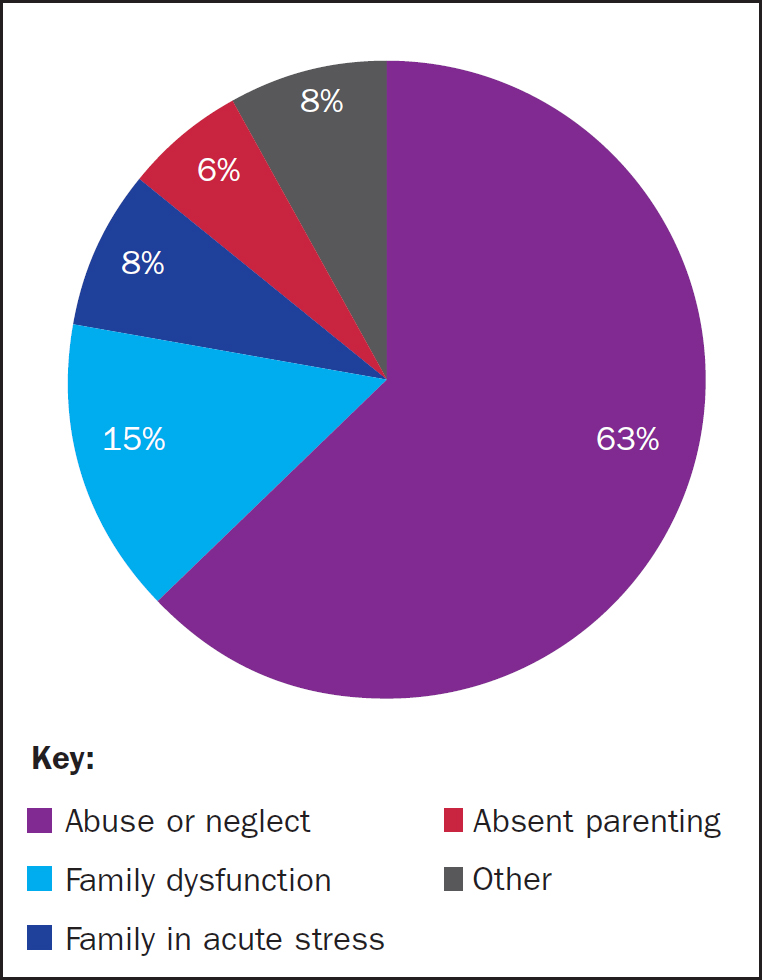

When a child is assessed by children's services, the primary reason for becoming a child in care is recorded. Abuse or neglect is the most common reason, recorded for 47 530 children and young people placed in care in 2018 (Figure 2) (DfE, 2018).

Where are they?

The majority of children are in foster placements. However, between 2014 and 2018 the number of those residing with a relative or friends increased from 14% to 18% (DfE, 2018). Children placed in children's homes, secure units or semi-independent arrangements make up 11% of the placements. In 2018, 6% of children under a care order were with their parents (DfE, 2018). This allows the local authority to ensure increased supervision.

Children tend to be placed in care near to their ‘home’, with the figures showing that 74% of children in care were within 20 miles of their home (DfE, 2018). However, this will vary depending on the type of placement required. For example, 41% of those placed for adoption were more than 20 miles from their ‘home address’. Between March 2017 and March 2018, 31% of children ceasing to be in care returned to their parents and 13% were adopted (DfE, 2018). Many cease to be children in care because they reach the age of 18 years and over, becoming ‘care leavers’.

Health outcomes for children in care

It has been argued for many years that children in care have greater health needs than their peers, especially in areas such as mental health and the management of chronic illnesses (Wood and Selwyn, 2017). Häggman-Laitila et al (2018) found that half of children in care have severe behavioural and emotional problems and almost half are developmentally delayed. When the health of those leaving the care system was considered, at the ages of 17 and 18 years they are two and four times respectively more likely to suffer mental health disorders than their peers who have not experienced care (Häggman-Laitila et al, 2018).

The literature has shown that, although more research is needed, physical health is an important personal resource for functioning well (Wood and Selwyn, 2017). Children in care need to feel the commitment and support of a carer, indicating the importance of the presence of a trusted adult. However, young people in care have also expressed the need to be trusted and given responsibility, having choice and involvement in decisions, to enable empowerment (Wood and Selwyn, 2017).

Health assessments

Accurate and contemporary personal health information has implications for the wellbeing of children and young people during their time in care and throughout their life because knowing your medical history is important to positive health care (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, 2015).

National statutory guidance states that children and young people in care should have a medical assessment on entry into the care system and then at routine stages throughout their time in care, usually undertaken by nurses in the public health sector (DfE and Department of Health (DH), 2015). This occurs 6-monthly for those aged under 4 years and annually for those over this ages. This process should inform the care planning for children and young people in care, allowing surveillance, proactive input and support (DfE and DH, 2015).

Conclusion

The Children Act 1989 provides a definition for children and young people in care. Data are collected annually about this vulnerable group, which, based on current figures, indicates that the number of those in care continues to increase (DfE, 2018). The most common reason for entering the care system is experience of ‘abuse or neglect’.

Children and young people in care are known to have poorer health and education outcomes. By recognising this, nurses are better able to appreciate the appropriate level of support that they will require and ensure that they meet the needs of children and young in care.