Cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (CAMPs), formerly referred to as skin substitutes, are a therapeutic class of materials that when applied can provide a barrier over open hard-to heal wounds. In the proper setting, these products have the potential to create a more favourable wound bed environment that can encourage granulation tissue growth as well as epithelial cell migration across the extracellular matrix, thus re-establishing the trajectory towards closure. Wound closure minimises infection risk, fluid loss, and reduces pain.

Prior and current nomenclature for skin substitutes

The term skin substitutes can be misleading in that these products do not fully replace the integumentum when applied, but most do replicate some properties of normal skin and are thus an important adjunct in the treatment of acute or chronic wounds (Shahrokhi, 2024).

This article reviews changes in the understanding and use of CAMPs that health professionals, such as tissue viability and community nurses who provide direct wound care, should know.

One of the original labels for this therapeutic class was ‘skin substitutes’ yet, as previously mentioned, to avoid the misrepresenting nature of this term, the phrase cellular and/or tissue-based products (CTPs) was adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) via a Local Coverage Determination (LCD) in 2016 (Wu et al, 2023). CMS added CTPs to the CMS Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) in 2019 (Boulton et al, 2018), and this terminology has been used predominantly in the literature since then. However, the expanding diversity of this therapeutic class now includes acellular and synthetic products, which makes the term CTP obsolete. As a result, these products were re-categorised by a 2023 consensus panel as cellular, acellular, and matrix-like products (CAMPs) to better reflect this ‘broad category of biomaterials, synthetic materials or biosynthetic matrices’ (Wu et al, 2023).

The classification systems used to categorise CAMPs are not regulated by any specific agency. However, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates the use of CAMPs in clinical practice (Tettelbach and Forsyth, 2023). The FDA has established several regulatory pathways for CAMPs: the pre-market approval (PMA) pathway, regulation of human-derived tissues that meet criteria under section 361 of the Public Health Service Act related to homologous use, and the 510(k) pathway. The PMA pathway is used for high-risk devices, while the 510(k) pathway is used for moderate-risk devices (Tettelbach and Forsyth, 2023).

Broad variety of CAMPs

Wound care nurses should be educated on the specific CAMP materials and how the product was developed for the unique and variable micro-environment of patients' wounds (Shahrokhi, 2024). CAMPs are classified into cellular, acellular, or matrix-like materials (Table 1) (Wu et al, 2023). Each of these categories has features such as the viability, number of layers and product source. CAMPs can be further categorised as epidermal, dermal, and composite grafts, based on the skin component they contain. Each CAMP has its own unique set of advantages and disadvantages. The choice of a CAMP depends upon the type of wound, its aetiology, and the skin component that requires replacement. In addition, the desired functional and aesthetic outcomes need to be considered (Shahrokhi, 2024).

Table 1. Compositional categorisation of cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (CAMPs)

| Category | Features |

|---|---|

| Cellular | Autograft (viable)Allograft (viable or nonviable)Xenograft (viable or nonviable) |

| Acellular | Allograft (viable or nonviable)Xenograft (viable or nonviable) |

| Matrix like | NaturalSynthetic |

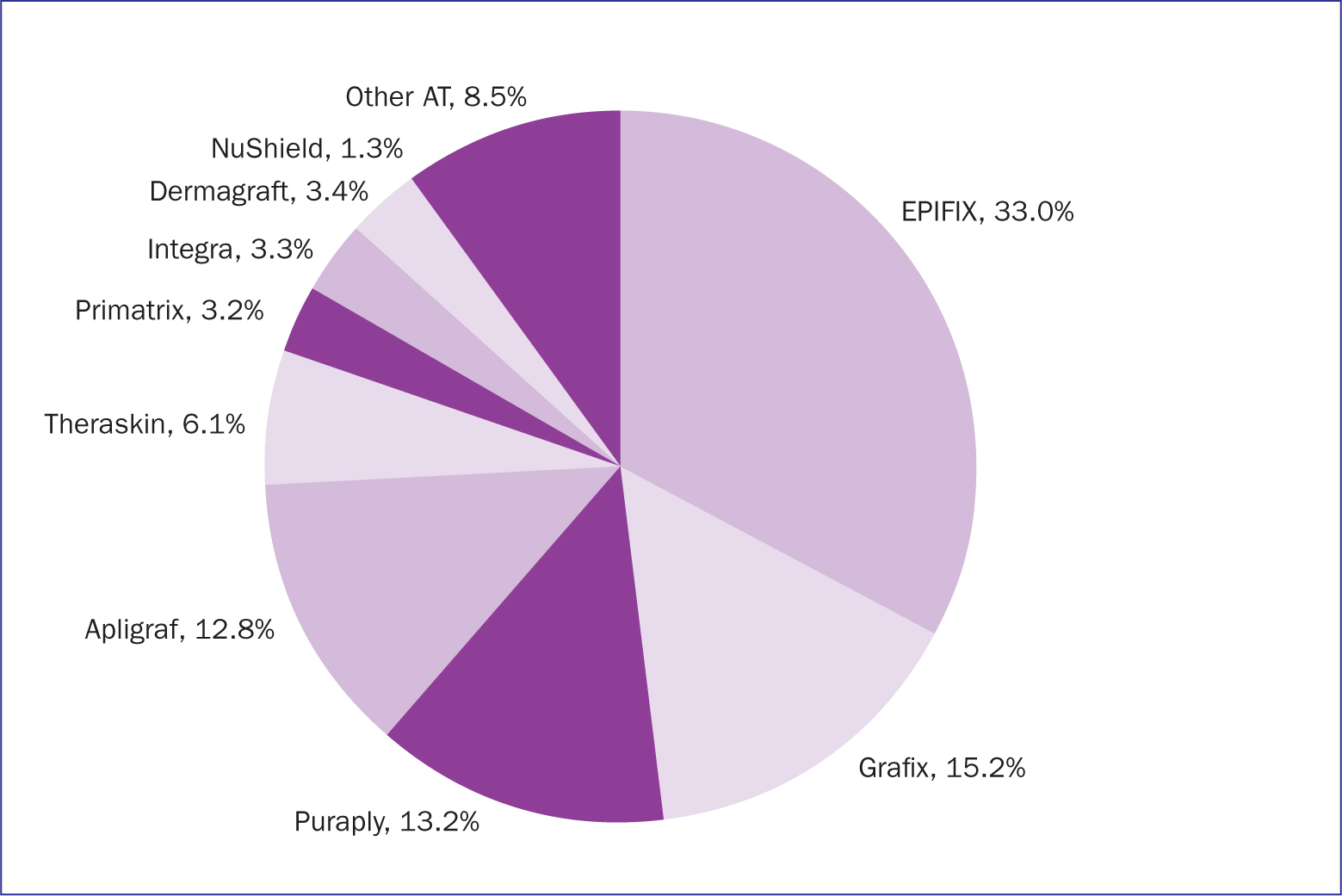

The most common matrix is a biological collagen layer, although synthetic options are available. When the source is human (allograft), collagen functions as biocompatible, biodegradable and high-tensile strength scaffolding. Many cell-surface proteins bind to the components of collagen (Orgel et al, 2011), which include the various receptors that promote cell adhesion and proliferation (Fiedler et al, 2008). Placental-based products have a collagen scaffold and are associated with a variety of regulatory and anti-inflammatory factors, which in utero are known to promote cellular recruitment, modulate inflammation, and stimulate tissue growth (Koob et al, 2014). In the US, a wide variety of CAMPs are used among Medicare enrollees (Figure 1) (Tettelbach et al, 2022; 2023).

There is a large number of CAMPs (Figure 2). Not all CAMPs have strong research supporting their efficacy. For instance, in 2020 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published a technical brief that described the various skin substitutes commercially available in the US and the research evaluating their efficacy. AHRQ evaluated 240 research articles for 76 CAMPs that were available at that time, Twenty-two articles were from randomised controlled trials, but only 12 were considered to have a low risk of bias (Snyder et al, 2020).

Usage

The use of CAMPs in hard-to-heal wounds is considered best practice among consensus experts as well as in peer-reviewed retrospectively published results analysing Medicare claims data (Schultz et al, 2004; Atkin et al, 2019; Tettelbach et al, 2022; Wu et al, 2023). Good wound care follows the consensus TIMERS approach (Box 1).

Box 1.TIMERS

- T for tissue: nonviable or deficient

- I for infection/inflammation

- M for moisture imbalance

- E for edge of wound, non-advancing or undermined

- R for regeneration/repair of tissue

- S for social factors that affect the trajectory of wound healing.

Source: Atkin et al, 2019

Wound care providers should evaluate the wound using TIMERS (Atkin et al, 2019) and take action accordingly:

- Tissue and provide sharp debridement as necessary

- Infection and inflammation should be monitored

- Moisture should be maintained

- Edge monitored to ensure it continues to advance and not become undermined

- Regeneration/repair therapeutics are utilised in stalled wounds and, that

- Social factors, inhibiting wound healing, are addressed.

JWCMasterclasses (2023) offers an interactive, case-based exploration on the role of CAMPs and the appropriate timing for applying a CAMP in chronic wounds.

When lower extremity wounds are provided with standard care but do not close by approximately 40-50%, depending on wound type, in 4 weeks, they are considered hard-to-heal and CAMPs are a suitable adjunctive therapy (Tettelbach et al, 2022; 2023; Wu et al, 2023). A common treatment pathway (Figure 3) highlights features of TIMERS and appropriate usage of CAMPs (Schultz et al, 2017).

Conclusion

The nomenclature for CAMPs has evolved to cover a broad range of synthetic, human and xenograft products that do not all offer the same degree of activity.

Optimal delivery of wound care should involve a multidisciplinary care team approach (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015), with the goal of promoting rapid wound closure to minimise the risk of associated complications such as infections, unscheduled hospital admissions and amputations (Lavery et al, 2006), which can unfavorably impact mortality rates, especially in people with diabetes (Armstrong et al, 2020). Framed in this context, if in 4 weeks a hard-to-heal wound does not close by approximately 40-50% it would be appropriate to consider stepping up to therapy with a CAMP (Tettelbach et al, 2022; 2023; Wu et al, 2023). Referrals from the community to hospital-affiliated tissue viability wound clinics are also an important part of the care network that connects patients with team members who can provide those struggling with hard-to-heal wounds with a broader scope of advanced treatments that potentially could include CAMPs.

Additionally, successful CAMPs treatment depends on thorough patient evaluation from an educated provider. The patient should also be given information on the CAMPs therapy, treated for all comorbidities, in conjunction with adequate wound bed preparation prior to CAMPs application. The literature supports the use of CAMPs in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds, including diabetic ulcers, venous ulcers, burn wounds, complicated surgical wounds and some skin disorders, although additional high-level evidence research is still needed to warrant universal acceptance of CAMPs (Wu et al, 2023)..