A global campaign to eliminate hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection as a major public health threat by 2030 was initiated by the World Health Organization in 2016 (World Health Organization, 2016). The UK went one step further, giving itself an accelerated goal of achieving this by 2025 (All-Party Parliamentary Group on Liver Health, 2018). The success of this campaign is critically dependent on an efficient testing process to identify infected individuals who would benefit from viral eradication therapy.

A new class of direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAAs) first became available in 2014. These are oral treatment regimens of 8–12 weeks' duration, which are free from side effects and, importantly, have cure rates in excess of 95% (Pawlotsky et al, 2015). A curative treatment has changed the landscape for testing people at risk of HCV infection because individuals can be linked into an England-wide network of HCV treatment providers.

Ongoing transmission of HCV in high-income countries occurs predominantly by sharing the paraphernalia used to inject illicit drugs. In the UK, 92% of anti-HCV tests where risk factors are documented are attributable to injecting drug use (IDU) (Public Health England (PHE), 2019). In the UK, most people who inject drugs will be imprisoned on at least three occasions and over 40% will have been in prison on five or more occasions (Health Protection Agency, 2012). The prevalence of HCV infection is 8% in prison populations in contrast to 2% in the community (PHE, 2015). Despite this, PHE (2014) reported that, in 2013, only 7.8% (16 309 of 208 552) of new admissions to English prisons were tested for the virus.

In response to this low level of test uptake an opt-out model of testing for all blood-borne viruses (BBVs), HCV, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was introduced in English and Welsh prisons in April 2014 (NHS England, 2013), following recommendation by PHE:

‘PHE is advocating the development of an “opt out” testing programme in prisons, whereby prisoners are offered the chance to test for infection near reception and at several time points thereafter by appropriately trained staff in a range of different healthcare services in the prison.’

The rationale behind this was that an opt-out approach to BBV testing had been successful in genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics and in antenatal services, so it might be applied in prison health care (NHS England, 2013; PHE, 2015). Prison healthcare services now have a target to test for BBVs in 75% of admissions (NHS England, 2018).

Test uptake in England rose to 32.3% in 2018-2019 and, although this is an improvement, it remains far short of the target (PHE, 2020). The aim of this review was to interrogate the available published literature that supports the opt-out BBV testing policy in English and Welsh prisons.

Method

A narrative approach was selected for the literature review. Three searches were conducted via the search engines EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL and Medline for articles published between January 2000 and February 2020 as follows:

- ‘Opt-out’ AND prison* OR jail OR correctional OR offender* OR inmate

- ‘Opt-out’ AND test* OR screen AND hepatitis AND prison* OR jail OR correctional OR offender* OR inmate

- ‘Opt-out’ AND test* OR screen AND HIV AND prison* OR jail OR correctional OR offender* OR inmate.

This time span was selected because the first effective antiviral treatments for HCV—pegylated interferon and ribavirin—were approved in 2000, as was stated in technology appraisal guidance [TA14] from National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) at the time, which has been superseded by TA75 (NICE, 2013), so there was a clinical reason to test people at risk. The search included literature detailing opt-out testing relevant to the UK and other high-income countries to support transferability to English prisons. Publications were excluded if they did not relate to BBVs, were descriptive overview papers, or were not from a high-income country.

Results

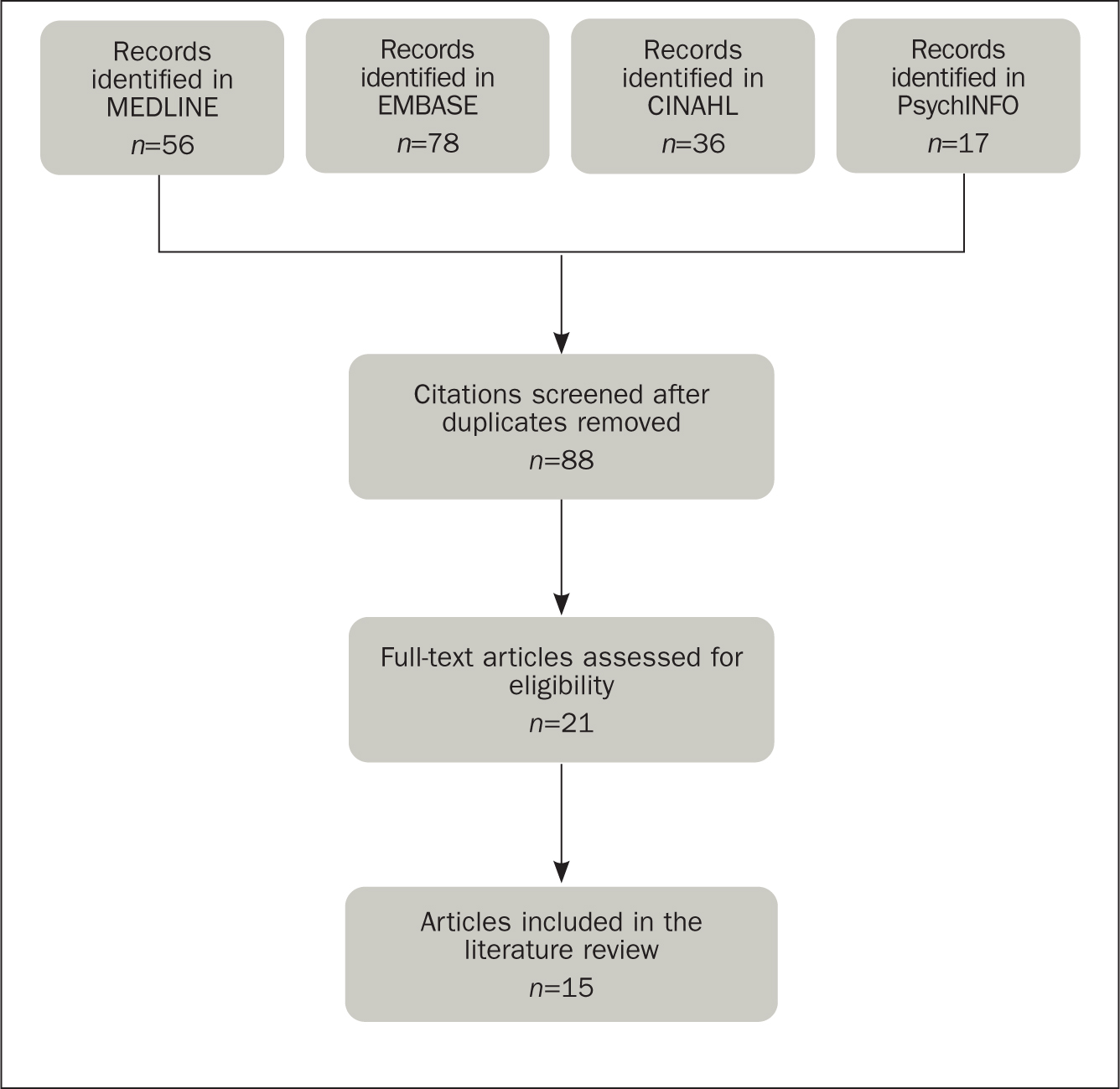

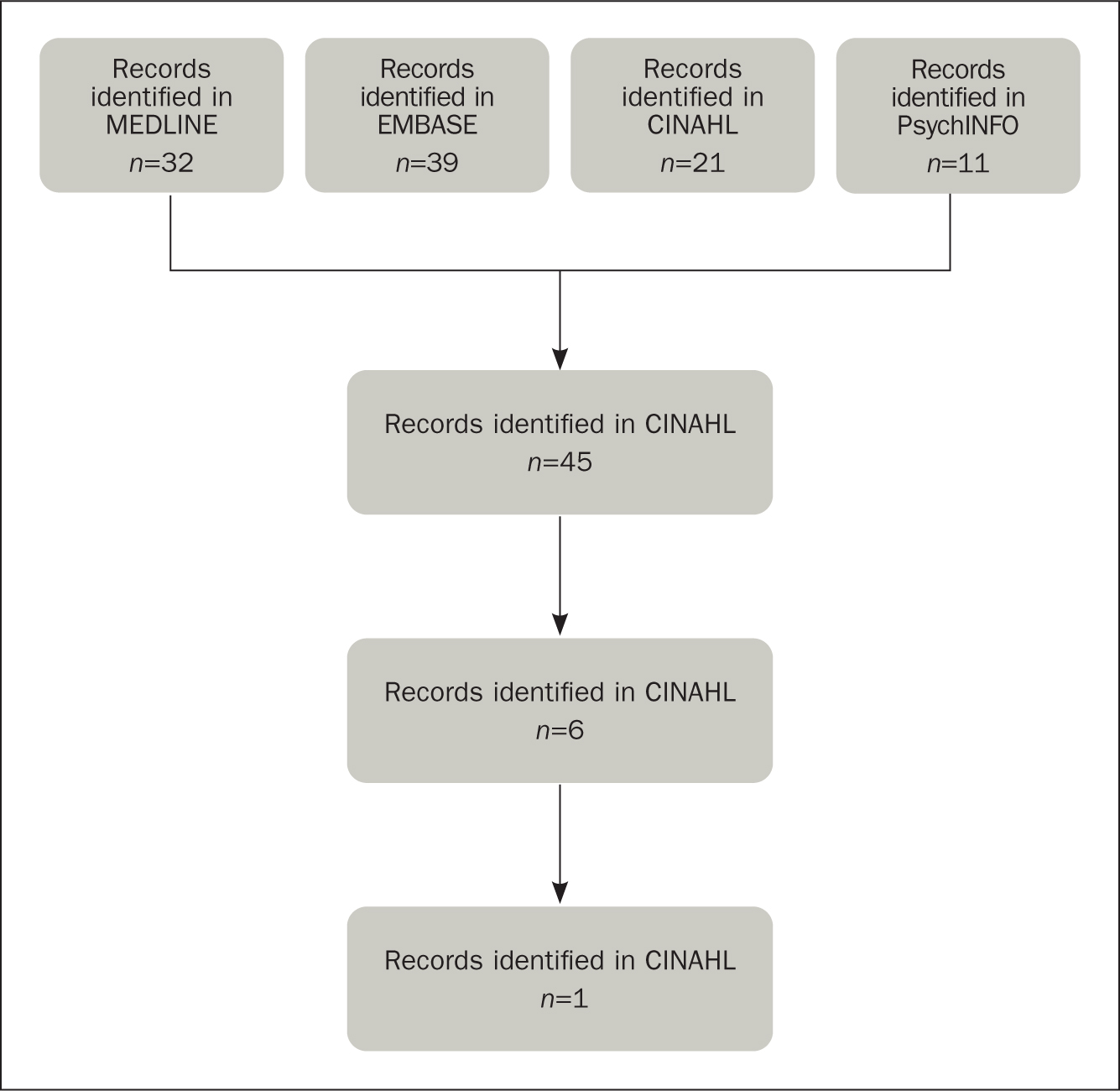

The first literature search in the selection process yielded 15 results (Figure 1). The second search criteria, focusing specifically on hepatitis testing in prison populations, yielded no suitable publications. The third search, for opt-out testing and HIV in prisons, yielded just one article (Figure 2). Sixteen publications were included in the review: 10 were from the USA, five from the UK and one from Eire. The methodological approaches used were: eight service evaluations (USA, 5; UK, 3), three abstracts (USA, 2; UK, 1), two qualitative enquiries (Eire, 1; USA, 1), two prospective controlled trials (USA, 2), and one literature review (UK). Overall, seven papers discussed HIV (all from the USA), a further seven discussed HCV (USA, 1; Eire, 1; UK, 5) and two included both viruses (USA, 2). No publications were identified that reported opt-out testing and HBV.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the literature selection process for opt-out testing in prisons

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the literature selection process for opt-out testing in prisons  Figure 2. Flow diagram of the literature selection process for opt-out testing and HIV in prisons

Figure 2. Flow diagram of the literature selection process for opt-out testing and HIV in prisons

The earliest papers were published in 2009: these were both prospective controlled trials undertaken in jails in the USA, a country that makes a distinction between jails and prisons. Jails house inmates awaiting trial or individuals with sentences less than 1 year and prisons are establishments for those serving longer terms. The two prospective controlled trials were by the same research team: one was undertaken in a female jail (Kavasery et al, 2009a) and the other a male jail (Kavasery et al, 2009b). These publications evaluated the optimal time to test people in prison (PIP) for HIV using an opt-out approach and a point of care oral fluid swab over a 5-week period. The three testing time frames were:

- Immediate: the day of arrival

- Early: during a required physical examination the day after arrival

- Delayed: 7 days after arrival.

The percentages of women tested in the immediate, early and delayed arms were 55% (59/108), 73% (79/108) and 50% (54/107) respectively (Kavasery et al, 2009a). The percentages of men tested in the immediate, early and delayed arms were 45% (46/103), 53% (52/98) and 33% (32/97) respectively (Kavasery et al, 2009b). The results from both studies showed that opt-out testing 24 hours after reception into the prison has a higher uptake.

The next group of publications are service evaluations of opt-out testing in prisons (nine papers and three abstracts) published between 2010 and 2019. In a conference abstract, Wohl et al (2010) reported that, over a 6-month period, 60% of PIP were tested for HIV using an opt-in scheme, and 90% were tested via an opt-out approach. A standard script was read aloud explaining to the PIP which tests would be carried out, including a mandatory blood test for syphilis.

A 5-year retrospective review of HIV screening of male PIP in the USA during their induction medical visit also found a greater increase in test uptake using an opt-out approach (Strick et al, 2011). Initially, the HIV test uptake was 5% (of 12 202), if requested by a PIP. An opt-in approach where the PIP were actively advised they would be tested if they consented resulted in 72% of (16 908) having a test. In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009) recommended routine opt-out testing for HIV in healthcare environments in which prevalence was estimated as being greater than 0.1%. This opt-out approach increased test uptake to 90% among 5186 inmates. The author noted that routine blood testing for syphilis occurred in the prison, and the HIV test was added to the same sample.

An evaluation of the introduction of the rapid point of care oral swabs test used when delivering opt-out HIV testing in US jails was conducted by Beckwith et al (2011). Routine opt-out HIV testing within the first 24 hours of arrival at jails has been in place since the 1990s, with an uptake of 70-80%, suggesting that the long-standing culture of HIV testing and staff commitment to undertake this test may have been key influencers. Over 12 months, 1364 prisoners were offered a test, with 98% accepting. Twelve prisoners tested positive, 11 of whom already knew their diagnosis. The testing process and findings reported by Beckwith et al (2011) correlated with the delayed timing arm in both of the trials undertaken by Kavasery et al (2009a; 2009b).

Another evaluation of an opt-out approach to HIV testing with oral fluid swabs for HIV was undertaken by Spaulding et al (2013) at a jail in Georgia, USA. Pre-intervention, a blood sample had been routinely drawn for syphilis testing and PIP could opt in to have this tested for HIV. Over a 3-month period in 2010, HIV test uptake using this approach was recorded as 43.2% (2253/5218). More than 1 year later, over a 14-month period (January 2011 to mid-March 2012,) after the introduction of the opt-out policy, the figure had risen to 64.3% (12 141/18 869). Thus, contemporaneously changing the test offer from an opt in to an opt out, and changing the test method from serum to oral fluid sampling, with results available in 20 minutes, effected an increase of 49%.

Rosen et al (2016) reported that in November 2008 the policy of testing new entrants to a prison in North Carolina, USA, changed from an opt-in to an opt-out approach. Initially, 58.8% of prisoners had opted in for an HIV test. However, following the policy change to an opt-out approach, this rose to 95.2% having the test. Strick et al (2011) and Rosen et al (2016) did not state whether a standard script was used when offering the test in the US institutions in their studies, whereas a script was used in the study by Wohl (2010), which may have impacted uptake. Doubts can be cast on the generalisability of this data to the UK, as the greater uptake compared with UK numbers when using an opt-in approach may indicate that there may have been other influencing factors.

The introduction of HIV and HCV testing using an optout approach in Dallas County Jail is reported by de la Flor et al (2017). Prior to the introduction of opt-out testing in June 2015, the combined uptake of HIV and HCV tests was 12.9% (118/915). By January 2016, after the change to an opt-out policy, uptake had risen to 80.5% (269/334). The key feature was adding HIV and HCV tests to all routine blood tests taken by the phlebotomists from November 2015. It is noteworthy that Strick et al (2011), Wohl (2010), Rosen et al (2016) and de la Flor et al (2017) all reported that the opt-out BBV test offered to PIP was to be added to a blood sample being taken for other clinical purposes. This observation is of critical importance to the success of an opt-out policy for BBV testing in English prisons, because the studies indicate that PIP are not necessarily averse to being tested if the process does not require additional interventions or effort on their part.

The first service evaluation of the effectiveness of the opt-out testing policy in the UK, at HMP Birmingham, was published by Arif (2018) 4 years after implementation. In 2013, none of the 6452 people entering the prison were tested for HCV within the first 30 days of arrival. Following the introduction of an opt-out policy and the dried blood spot (DBS) test method in 2015, uptake rose to only 7.6% (380/4998). The paper by Arif (2018) did not specify the exact opt-out phrase used, when or where testing was offered or conducted, or the reasons for test refusal. However, it noted that prison officer understaffing increases the difficulty in accessing PIP; it also noted that the DBS test was preferred to venepuncture. A further opt-out evaluation conducted in the UK at HMP Pentonville, London (Ekeke et al (2018), found that between December 2015 and February 2017 95% (6450/6769) of PIP were offered BBV optout testing, of whom 21% (1324/6450) had accepted. Reasons for not having the test included:

- The way opt-out testing was communicated

- Simple refusal by the person

- How easy it was to access testing.

Both English service evaluations (Arif, 2018; Ekeke et al, 2018) reported that there may be difficulties accessing PIP to discuss and perform a healthcare intervention, and that the mere introduction of an opt-out approach is unlikely to have the desired effect.

The most recent US publication reviewed was an evaluation conducted across 16 Washington prisons (Assoumou et al, 2019). The authors retrospectively analysed the outcomes of optout testing carried out between 2012 and 2016. Over this period, a total of 83% (24 567/29 624) PIP were tested, of whom 20% (4921/24 567) were anti-HCV positive. Within the overall number tested, the study separately looked at a cohort of PIP born between 1945 and 1965 and found that a higher proportion were anti-HCV positive (44%; 1367/3084). The researchers further looked at individuals born at any time with a history of IDU and found that an even greater number were anti-HCV positive (53%; 1878/21 483). Despite these percentages, it is important to note that a high number of those diagnosed with HCV (35%) were outside the birth cohort or did not have a reported history of IDU, and so a solely risk-based targeted testing approach would have missed these. This publication therefore supports the value of an opt-out and non-targeted approach to BBV testing in prisons.

An evaluation of the impact of the opt-out approach to testing in 14 East Midlands prisons in England was conducted by Jack et al (2019). In the 12 months before the opt-out policy, 1972 PIP were tested in contrast to 3440 in the first 12 months following the implementation of an opt-out approach. Between July 2016 and June 2017, 13.5% (2706/20 075) people were tested with a between prison range of 7.6% to 40.7%. Thus, the opt-out testing policy did not bring about the desired substantial increase in test uptake.

A prospective study comparing the opt-out approach and the DBS test method with the rapid result oral fluid anti-HCV test and capillary viral load test if needed was conducted in HMP Wormwood Scrubs, London (Mohamed et al, 2020). Between September 2017 and December 2018 46.6% (2442/5239) people were tested using the DBS test method. Between September 2017 and December 2018, PIP on the substance misuse wing were approached using an opt-out approach using the oral fluid swab test method. Test uptake among this subgroup was 89.5% (162/181). It is not clear whether this success was due to the different test method, or because this population was more willing to be tested as they recognised they may have been at risk of acquiring HCV infection, or whether the healthcare staff were more effective in delivering the intervention because it was part of a study. However, it does suggest that the type of test method used has a role in encouraging uptake.

The literature review by Francis-Graham et al (2019) concluded from 60 publications that the factors affecting the offer of a BBV test to PIP were:

- Timing of test offer

- Capacity to consent

- Prioritisation of prison security regimens

- Healthcare teams' capacity

- Refusal to attend appointments

- The administration processes.

Factors affecting test uptake were:

- Confidentiality and stigma

- Coping with a positive diagnosis

- Fear of needles

- The interpretation of risk

- Opt-out fidelity

- Institutional distrust

- Concerns that people were tested without the capacity to consent or dissent.

Finally, the two qualitative enquiries each had a different focus. First, Crowley et al (2018) conducted focus groups with 46 PIP across two prisons in Dublin. The opt-out approach to prison BBV testing has not been introduced in Eire, but this was a proposal made by participants. The second qualitative study (Ly et al, 2018) took place in a North Carolina jail, where 30 PIP were asked their preference for an opt-out or opt-in approach and were read examples of standard scripts for each option. The opt-in approach was preferred by 63% (19/30) because it gave them a choice. The participants who preferred an opt-out approach responded that it did not single people out for having an identifiable risk factor. One emergent theme regarding factors that affect testing decisions was the desire to exercise choice.

Discussion

This narrative review identified 16 papers published between 2009 and 2019. The emergence of UK publications from 2018 is a likely reflection of the introduction of the opt-out testing policy. The papers identified varied widely in terms of methodological quality. Furthermore, there are so few papers that addressed opt-out HCV testing in prisons that inferences and insights have been drawn from other publications that include or focus on HIV. In addition, there is limited evidence from countries other than the UK and the USA.

In England, there is a commissioning requirement to test for HBV and HIV in addition to HCV. It is therefore possible that the requirement to screen for HIV may deter some PIP from agreeing to be tested, but this has not been explored in the literature. The data reviewed confirm a modest increase in HCV test uptake in prisons when an opt-out approach is used. However, there are indications that several contextual or operational features of prison health care may be contributing to the difficulties in achieving the target of testing 75% of people entering prison.

This narrative review has not sought to specifically identify publications detailing the psychology of being tested for a BBV, but the papers by Francis-Graham et al (2019) and Jack et al (2020) illustrate that both felt and enacted stigma impacted negatively on test uptake. Furthermore, both Francis-Graham et al (2019) and Jack et al (2020) noted inconsistencies in the definition, understanding about and the delivery of an opt-out approach by prison nurses. An opt-out approach to BBV testing has been defined as advising people that they will be tested unless they opt out of the intervention. In contrast, an opt-in approach is where people are advised that testing is available, and that they can choose to have this carried out, if they wish (Basu et al, 2005).

The opt-out approach to testing for BBVs in the UK originated from a desire to increase antenatal HIV test uptake in Edinburgh, where only 1% of women were being tested, employing an opt-in approach (Simpson et al, 1998). A subsequent study demonstrated that the introduction of an opt-out approach (defined as routine testing, unless specifically declined through verbal consent), in conjunction with a leaflet explaining the tests to be conducted, increased uptake rates to 88.3% (Simpson et al, 1999). As a result of this astonishingly high response, UK antenatal services adopted opt-out HIV testing the same year (NHS Executive, 1999) and added HBV testing in 2000.

Although an opt-out approach to BBV testing is clearly effective in antenatal and GUM clinics, the crucial difference is that people purposefully attend these clinical environments to seek healthcare advice, tests, results or interventions. In contrast, PIP are seen by a nurse as part of the procedures mandated on arrival at a prison when they are actively offered BBV testing during the initial nursing assessment (HM Prison Service, 2004; 2006). The evaluations by Wohl (2010), Strick et al (2011), Rosen et al (2016) and de la Flor et al (2017) reported testing rates in excess of 80% in jails when an HIV test was added to a blood sample already obtained for other purposes, such as mandatory syphilis testing. However, in the UK, PIP are not routinely tested for syphilis, as they are in the USA, so the blood test for a BBV is not combined with a blood sample obtained for another clinical purpose. The differences in healthcare delivery protocols between the UK and the USA have not been specifically unpacked in any literature. Therefore, while these differences per se may indeed explain the variation in test uptake between these countries, it is not possible to draw a firm conclusion.

The optimal test method to use in conjunction with an opt-out approach is not clear and the alternative approaches warrant further investigation. The studies by Kavasery et al (2009a; 2009b) and Spaulding et al (2013) showed that an optout approach and the use of an oral fluid swab are effective combined interventions to achieve high testing rates. A different opt-out approach was evaluated by Wohl (2010), Strick et al (2011), Rosen et al (2016) and de la Flor et al (2017): in these studies, PIP were advised that venous blood, collected for another purpose, could be used for testing with their consent.

The timing of a BBV test offer is also relevant. The results of controlled trials by Kavasery et al (2009a; 2009b) reflect the findings of an earlier study by Vallabhaneni et al (2006), who showed that prisoners were more likely to accept HIV testing the day after arrival in prison after they have had time to commence the process of psychological adaptation to being imprisoned. Reports from both PIP and prison nurses in a recent qualitative study by Jack et al (2020) confirmed this emotional response, particularly if people arrived straight from court. However, there is insufficient robust data to inform a specific optimal day to conduct testing. Further data are also required to assess the acceptability of the different testing methods in combination with an opt-out approach, and to further understand the reasons why PIP may decline BBV testing.

Conclusion

An opt-out BBV testing policy in prisons can lead to a modest increase in uptake, although as a sole intervention it is unlikely to enable the 75% target to be achieved in England. Two important distinctions between GUM or antenatal clinics, and prisons, have been overlooked by policy makers; first, that in the case of GUM and antenatal clinics, people attend of their own volition, and, second, that those attending are not in a coercive psychosocial cultural context of a prison, which may affect the decision-making process.

A further important difference between the US and UK prison healthcare systems is that PIP in the UK do not have blood samples taken routinely to which a BBV test can be added via an opt-out approach. Policymakers need to consider the prison context carefully when planning additional interventions to enable the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health problem in prisons.

KEY POINTS

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a blood-borne virus that is completely curable with an 8–12 week course of side-effect-free medication. The World Health Organization has a stated objective to eliminate viral hepatitis by 2030

- There is a higher prevalence of people with HCV in prisons as some will have been infected by sharing contaminated drug injecting equipment—these are important locations in which to test and identify people who have HCV infection so they can be treated

- There are ongoing difficulties in achieving the 75% test uptake target set for English prisons. The literature reviewed shows that the prison context of delivering health care and people's responses to a test offer differ from those in hospitals or community settings, so a different approach may be required to effectively screen the prison population for HCV and other BBVs

CPD reflective questions

- Think about why it is it important to eliminate viral hepatitis (HCV) and why it is important to tackle it in prison populations

- Consider the reason why people in prison might refuse to be tested, and ways in which these might be addressed

- Reflect on the benefits of being cured of HCV for the patient, their family and friends, as well as for wider society