References

COVID-19 outbreak management in a mental healthcare setting

Abstract

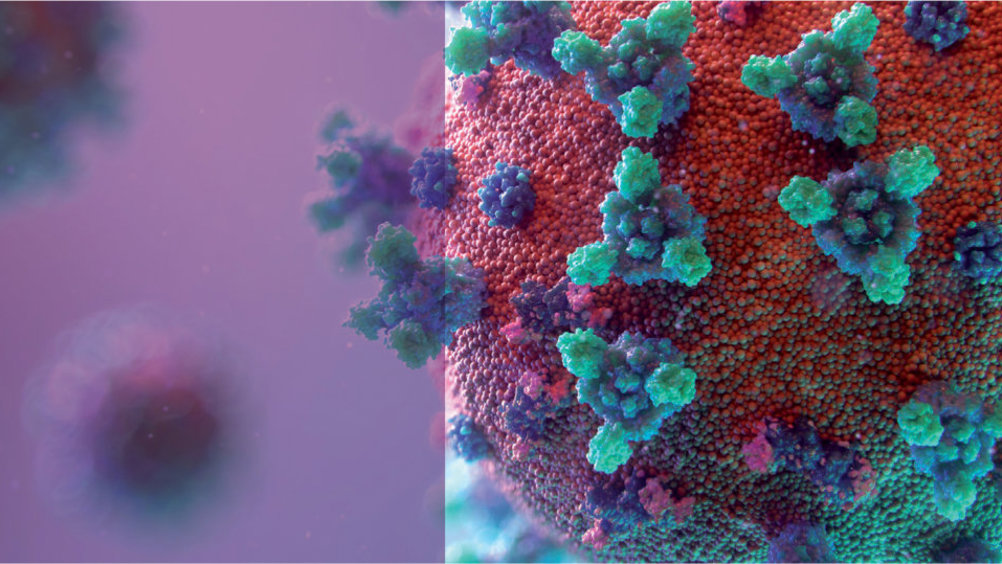

Since the beginning of the novel coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19), inadvertent exposure of hospitalised patients and healthcare workers has been a major concern. Patients in inpatient settings with mental illnesses have also been impacted by the restrictions the pandemic has caused, with many having experienced the confines and loss of liberties that COVID-19 has brought. This article identifies the infection prevention and control measures required in a mental health setting during an outbreak of COVID-19. The focus is on the challenges of working in a mental health setting and identifies the difficulties in containing the infection within this ill-designed built environment and includes the additional pressures of managing this complex and diverse group of patients. Current guidance on outbreak measures is given with particular attention applied to the patients, the practices and the environment.

In 2020, COVID-19, an infection caused by a novel coronavirus, transmitted significantly on NHS wards, exposing patients to a viral infection that could be fatal and which produced significant implications for patients and healthcare workers (HCWs). Outbreaks placed an additional burden on already stretched resources (Taylor et al, 2020). By early 2020, infection rates had soared in UK hospitals with data published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showing a significant increase in mentions of COVID-19 on death certificates in England and Wales (ONS, 2020). The UK had registered 73 621 coronavirus-related deaths before 2021 (Worldometer, 2021). Mental health settings were also severely affected by the fallout of the pandemic, with HCWs trying to control the transmission and suddenly dealing with challenging outbreaks of infections that had not been experienced before and having to treat patients suffering the effects of the virus in a confined environment that was ill-designed for treating patients with such a virus (Rodgers et al, 2021).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting British Journal of Nursing and reading some of our peer-reviewed resources for nurses. To read more, please register today. You’ll enjoy the following great benefits:

What's included

-

Limited access to clinical or professional articles

-

Unlimited access to the latest news, blogs and video content