People with lymphoedema need appropriate and timely advice, support, and sometimes hands-on expert treatment in order to manage their condition. Without appropriate intervention, this progressive chronic condition can cause increasing distress, disability and deformity through swelling of limbs, trunk or face, and through damaging changes to the skin become at risk of cellulitis infections (Fu et al, 2013). Although lymphoedema can make a person more vulnerable to skin infections, it is not thought to increase the risk of contracting COVID-19 nor of increasing the severity of symptoms, except in a rare version of lymphoedema that affects the lungs (Lymphoedema Support Network and Lymphatic Education and Research Network, 2020). The reality, however, is that a significant proportion of patients on a standard, mixed lymphoedema caseload have co-morbidities that may make them vulnerable (Al-Niami and Cox, 2009; Son et al, 2019). The issues of shielding, reducing personable contacts and isolation therefore become particularly relevant to this population.

The traditional pattern of lymphoedema consultations have been regular in-person, face-to-face consultations, which allow the lymphoedema specialist health professional to assess subtle changes to skin condition and sub-dermal texture and thickness. Palpation and detailed measurement are staple parts of the evaluation of the condition. These are commonly followed by patient instructions on the necessary skin care and personalised exercise and lymphatic massage routines for self-care and individual fitting for compression garments. Traditional lymphoedema outpatient care therefore required the therapist to be in close proximity to the patient for a significant part of the consultation.

Lymphoedema services have had to adapt as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic and to the wider service impact of longer-term rehabilitation of sufferers (Gabe-Walters and Noble-Jones, 2021). A need to reduce patient travel and non-essential in-person contact is superimposed on longstanding commitments to value-based health care, effectiveness and efficiency, while maintaining continuity of care (NHS Wales and Welsh Government, 2019). Adapting provision to incorporate remote consultation, not just as a response to the pandemic but as a long-term aim, can add value for the patient and reduce breaches of patient contact targets to full commissioned service requirements. However, as services are restored and reset, obligations to legal and governance frameworks remain. Therefore, changes to standard operating procedures must be risk assessed eg clinical and quality impact assessments (CQIA), data protection impact assessment (DPIA) and equality impact assessments (EQIA).

Advice and guidance for lymphoedema teleconsultation: video consultation, telephone triage and remote working

This document presents pragmatic guidance for lymphoedema services. It is based on analysis of the national response of Lymphoedema Network Wales (LNW) during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic and incorporates contemporary guidance in parallel specialties such as dermatology (British Association of Dermatologists, 2020). It can be used alongside current process changes in secondary and primary care to maintain urgent services, optimise use of clinical staff, minimise additional work for community nurses, physiotherapists and GPs, and provide continuity of care with remote management of the patient where possible. Although clinical and non-clinical staff need to comply with their own organisations' guidance and guidance from commissioners, this document aims to provide specific guidance and share good practice in relation to lymphoedema management. Where specific platforms such as DrDoctor (https://www.drdoctor.co.uk/about) are in use, some steps may be automated to optimise communication between therapists and patients. For example, patient-reported outcome measures, used to plan care in line with patient needs, can be easily shared with patients and reviewed by therapists using digital systems. LYMPROM, is one such lymphoedema-specific patient-reported outcome measure that has been piloted using a digital platform.

Key principles

- Up-to-date referral process information needs to be readily available for health professionals in primary and secondary care to refer patients to local lymphoedema services to triage the urgency of the appointment required. Referrals should be sent using approved systems or using a secure NHS email

- Triage of referrals must have a clear process and definitions of urgent/advanced disease

- Manage referred patients by switching face-to-face clinics to teleconsultation with or without video consultation where possible (new and follow-up). Where not possible, clear standard operating procedures are needed for in-clinic (face-to-face) consultations and domiciliary visits (reflecting local community nursing processes)

- Optimise remote access to allow lymphoedema staff to continue to provide patient care from home if required

- Establish patient consent policies for receiving, reviewing and storing patient images from health professionals and patients

- Facilitate virtual staff team meetings to coordinate patient care.

Managing referrals

On receipt of a referral all patients should be contacted by telephone within locally agreed timelines (or, if unsuccessful, letter sent requesting patient to contact the service), to establish whether a teleconsultation or face-to-face lymphoedema appointment is required, and whether in-person contact would be in a clinic or through a home visit. For lymphoedema patients LYMPROM can be used as a triage tool to identify those with a burden of symptoms that may require an urgent face-to-face appointment instead of a teleconsultation appointment. Triage question templates can be useful, these would include significant/relevant past medical history and allergies.

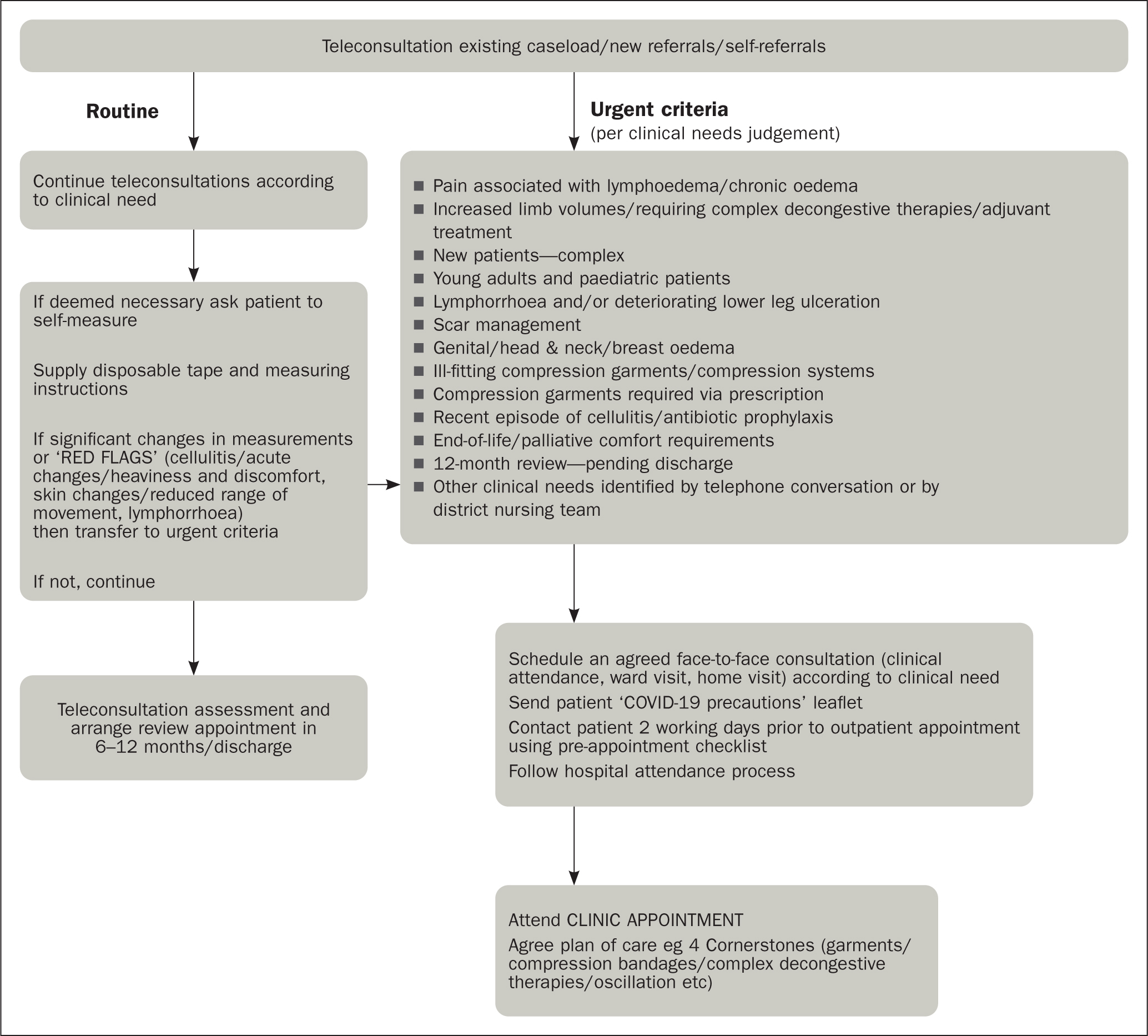

Teleconsultation appointments should be used when there is no specific need for face-to-face contact (see Figure 1). However, there is a significant minority who are not online—in Wales this was found to be 12% of people in 2019-20 based on a sample size of 12 400 (Welsh Government, 2021)—so lymphoedema service providers need to remain aware of services that can support these people, such as Digital Communities Wales (https://www.digitalcommunities.gov.wales/).

Those patients requiring a face-to-face appointment due to clinical problems or those on the urgent list should be given an appointment, subject to government advice at the time, and reminded of any local precautionary measures such as face coverings. Patients should be offered the opportunity for a telephone or video consultation at their previously allocated face-to-face appointment time-slot if possible. Trusts or health boards may already have an established videoconferencing solution such as NHS Attend Anywhere (https://www.attendanywhere.com/journey.html) or accuRx (https://www.accurx.com/).

If, during the triage call, a face-to-face appointment is made for an imminent date, reduce the risk of attendance with COVID-19 by establishing whether the patient has any symptoms as per contemporary government advice, eg new persistent cough, temperature, loss of taste. Similarly, for appointments made further ahead of time, a telephone call to the patient should be made in the days immediately before the appointment to check they are free of COVID-19 symptoms.

People wanting to cancel face-to-face appointments should be given the option of a new appointment, ideally within 1 month to a maximum of 6 months' time, based on patient need. Ideally, this appointment should be given during the phone call. People should be advised to contact the service if they need to be seen earlier due to a change or new clinical problem related to their lymphoedema.

NHS Digital (2020) has produced advice on e-referral service features that many help organisations during the current situation to manage routine referrals, monitoring provider worklists and managing cancellations.

Urgent care

Patients (adults and children) with the following urgent clinical needs should be seen in person whenever possible, if they want to attend and have no flu-like symptoms:

- New or increasing pain associated with their lymphoedema

- Leaking lymphorrhoea (consider joint working with community nurses or other local health professionals)

- Genital oedema affecting micturition

- Head and neck oedema affecting breathing or swallowing

- Uncontrolled oedema requiring a new compression garment

- End-of-life/advanced disease and requires assessment due to uncontrolled oedema

- Any other clinical or technical reasons identified from the telephone conversation that may be relevant, including a complexity of need that cannot be reviewed over the telephone.

Figure 1 gives an example protocol for identifying cases that may be considered urgent and may require a face-to-face outpatient appointment. Work with administrative support if necessary to ensure that booking slots are adjusted to protect urgent slots.

Images and messaging

Lymphoedema services provide support and guidance to primary and secondary care, as well as care home staff, for example, when managing leaking legs, wounds or cellulitis and oedema in end-of-life care. These situations, as well as many others, are improved by the availability of images; however, it is imperative that photographic consent and confidentiality is considered. Secure clinical image smartphone apps can enable patients to have images taken in the GP surgery, which may help the lymphoedema service to give advice or guidance to community teams (check with local governance/IT departments). Similarly, if local services are seeking advice from national/specialist level consider the use of these apps or local medical photography.

Mobile messaging can also be used to communicate with colleagues and patients/service users as needed; however, before using commercial applications such as WhatsApp you should check with the latest local information governance regulations.

NHSX (the body responsible for transforming digital health technology in England) has produced information governance advice recognising the unprecedented challenges we are all facing during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly when there is a need to share information quickly for urgent or end-of–life care (NHSX, 2020). Further advice is provided by the Information Commissioner's Office, the National Data Guardian and NHS Digital.

Always consider what type of information you are sharing and with whom, and as much as possible limit the use of personal/confidential patient information. Other commercial medical smartphone apps that can support sharing of clinical information securely between health professionals are Consultant Connect, Pando and Hospify. Some departments have set up a central nhs.net email address or use individual nhs.net mail for photographic images transfer between health professionals, so check locally. Patients should be advised that emails sent from personal email addresses to nhs.net addresses are not guaranteed to be encrypted.

Advice and guidance

A clear process of accessing advice or guidance should be available to health professionals without the need for patient referral. Similarly, all service staff should be aware of where to direct enquiries from members of the public if they are not existing patients or their carers. Patient expectations can be managed through clear information about changes to services. This needs to be clear, accessible and available in as many formats (and languages) as is practicable. Signposting to suitable online information and videos such as those produced by PocketMedic (http://www.medic.video/w-lymph) can be very helpful.

Teleconsultation

Where teleconsultations take place, in line with all consultation processes, precise and systematic records are compulsory.

COVID-19 information governance advice (NHSX, 2020) encourages the use of video-conferencing to carry out consultations with patients and service users to reduce the spread of COVID-19, but you are strongly advised to check local guidelines before using generic video-conferencing tools such as Skype, WhatsApp, or FaceTime—your organisation may have elected to use other commercial products designed specifically for this purpose. Safeguard personal/confidential patient information in the same way you would with any other consultation. In most environments the consent of the patient or service user is implied by them accepting the invite and entering the consultation (see section on patient consent for more detail).

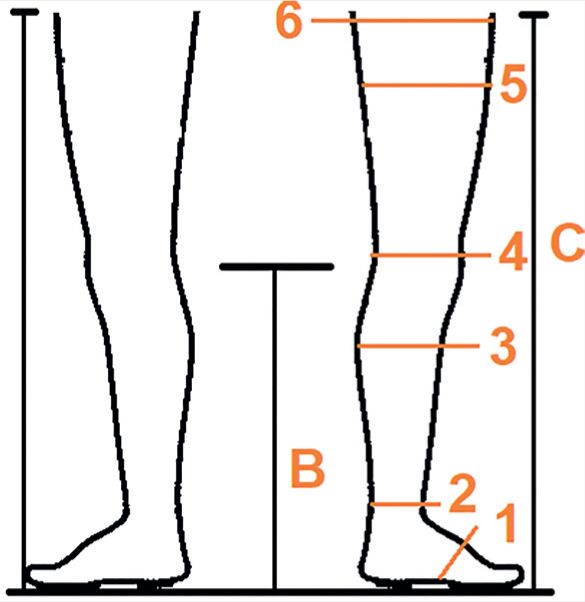

If compression garments are required for teleconsultation patients they can be posted out, or delivered directly by some suppliers (check that the patient agrees to a third party having their details). Examples of points to be covered in measuring guidance for patients are included in Box 1.

Box 1.Information included in Lymphoedema Network Wales home measurement guidance sheets for patientsTo measure the size of your leg, you will need a tape measure with centimetres and millimetres marked on it. The tape measure needs to be of the soft variety, for example a tailor's or dressmaker's tape measure.If you do not have one of these, you can use a piece of string and a DIY tape measure to measure the string, but this is not as accurate.DO NOT USE A METAL DIY TAPE MEASURE DIRECTLY ON YOUR SKIN AS IT CAN CAUSE CUTSGeneral techniqueMake a note of what position you are in to do the measurements, for example, sitting in the chair with your legs down or with your legs up on the bed or settee, and if you are doing it yourself or someone else is doing it for you. Write which limb you are measuring and state if it is left or right.Using the tape, keep the tension even:

Correct

Incorrect

Hand held tape measure: place the tape measure snugly around the limb without tightening the tape (hold the tape to prevent it slipping/falling down)Make a note of the number on the tape in centimetres and millimetres, whether it is a left or right leg being measured.Leg lower limbIt is best to measure in sitting position or with legs up on the bed or settee (elevated), make a note of the position you are in to do the measurement.Measure how long your leg is, there are 3 measurements, your shoe size, the length of your lower leg and the length of your whole leg. You can write all of the measurements in centimetres and millimetres on the table.

- Shoe size (UK or European)

- Heel to knee crease (line on back of knee)

- Heel to gluteal (bottom) crease

Then measure the circumference of your foot and leg:

- Around foot

- Ankle

- Calf (widest part)

- Knee (at level of crease behind knee)

- Thigh (widest part)

- Groin (as high as you can)

Recording your measurementsHow tall are you?What position were you in?Sitting on a chair ☐Legs up (on settee or bed) ☐Who did the measurements?I did ☐Someone else ☐

| Measurement | LEFT | RIGHT |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement A – shoe size (UK or European) | ||

| Measurement B – heel to knee crease (line on back of knee) | ||

| Measurement C – heel to gluteal (bottom) crease | ||

| 1. Around foot | ||

| 2. Ankle | ||

| 3. Calf (widest part) | ||

| 4. Knee (at level of crease behind knee) | ||

| 5. Thigh (widest part) | ||

| 6. Groin(as high as you can) |

Patient consent

Photographic consent policies vary across organisations. Discuss this with your healthcare organisation information governance and medical photography teams. The following guidance relates to lymphoedema services in Wales, during and post-COVID-19.

Consent is required for patient images to be used for patient care, including diagnosis or triage. The consent process should be revisited at each patient contact to:

- Inform the patient that there may be a difference between the accuracy of clinical care using photographs compared with face-to-face clinical assessment

- Explain how the images will be used, transmitted and stored in the healthcare organisation

- Obtain wider consent for teaching/publication/research if relevant. If consent to wider use is obtained, document the nature of the consent in the patient notes and review points to note in practice

Written consent is recommended where possible. However, where planned face-to-face consultations have been changed to non-face-to-face consultations then written patient consent may not be possible or practical. Where verbal consent only is given, the health professional should document this and consent would not extend beyond direct provision of care.

Specific considerations when patients capture and transfer their own images

Normally, patient images would be sent to lymphoedema services from GPs or other health professionals via secure transfer (using e-referral services or other approved platforms). During the COVID-19 pandemic, many new temporary pathways for transfer of patient images to lymphoedema services had to be established under local guidance, including direct transfer of images from patients using generic email services or mobile messaging. These still images were used to support telephone consultations where video consultation were not possible or when preferred by the patient (Figure 2). It is likely that these processes will be reviewed for safety in the post-COVID-19 period.

Points to note in practice

- If a clinician requests that the patient sends images or the patient offers to send their own images, patients need to understand that there are the usual risks associated with sending any images via the internet. This constitutes a non-secure transfer and images are not subject to information governance and data protection until they have been received by the health professional—in the same way as any images patients take and hold on their own phones may not be secure

- Once the image has been received by a health professional, any onward data transfer and storage should meet the NHS data protection and information governance requirements of the healthcare organisation

- If a clinician requests that the patient sends images, the routine documented consent process should be undertaken verbally and documented with a message explaining consent (eg ‘by sending these images you consent to them being held in your medical record’) or by sending a written patient consent form for the patient to complete and return

- Where images are suitable for teaching, consent forms can be sent to patients electronically and either completed electronically (eg with e-signature) or patients can return a photograph of the completed printed form

- It is advised that images, even when supplied by the patient, be retained when they have been used to make clinical judgements on patient care. If patients do not wish to have their images stored in their hospital record the clinician should check local policy, this may allow a pragmatic option of patients retaining the image. Similarly, a ‘still’ form of video-consultation (where no data is stored eg NHS Attend Anywhere) needs the same consent from patients to be retained (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Clinical staff working from home

Members of staff may be frequently away from their usual place of work for the foreseeable future due to social distancing or isolating for different reasons. Some staff will already have hospital laptops with a virtual private network (VPN) allowing access to hospital systems from home. Hardware requests for laptops, and issuing of VPN licences was accelerated across hospitals so that most staff requiring equipment should by now have them. However, if this is not the case, please discuss with your hospital's chief clinical information officer, service manager and IT teams.

Hospital-approved laptops with VPN software can allow lymphoedema specialists working from home to provide:

- Advice and guidance to GPs, community nurses and physiotherapists, patients and peers

- Remote triage of patient referrals

- Telephone consultations with access to electronic patient records and blood results.

Commercial platforms used through NHS contracts enable users to work on non-NHS equipment from home within VPNs. If working from home, however, staff need to remember that confidentiality remains essential. Family and friends in the same or adjacent rooms should not be able to hear conversations or see screens/documents, therefore arrangements should be made to accommodate achieving this and equipment such as headphones can be useful.

Virtual staff team meetings and education

Throughout the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic a rapid change over was made to enable virtual meetings supported by NHS mail, Zoom, Microsoft Teams or Cisco WebEx. This grew to include the provision of online education as staff grew in familiarity and confidence with the software. Staff need to check which platforms are approved for use locally or seek permission to use alternatives.

Conclusion

In light of recent spikes of COVID-19 and further lockdown scenarios, it is imperative that lymphoedema services have a means to provide suitable care for patients. Although face-to-face appointments are sometimes deemed necessary, many patients can be suitably supported via telehealth consultations. These guidelines may help lymphoedema services restore and reset in a safe and acceptable manner.

KEY POINTS

- During the COVID-19 pandemic it was not initially possible for people with lymphoedema to be seen face-to-face at lymphoedema services due to the potential risks of the virus and impact on services and wider society

- Teleconsultation appointments for lymphoedema services were developed providing telephone or virtual means to proactively manage patients with lymphoedema

- Guidelines were necessary to ensure a pragmatic consistent approach in patient management

- Incorporating remote consultations can bring wider benefits to service delivery and may add long-term value for patients and the NHS

- COVID-19 challenges will be enduring, yet patients have to be appropriately managed and services must adapt as necessary

CPD reflective questions

- How can the NHS effectively manage its patients via teleconsultation?

- Consider which other similar health conditions could be managed in a virtual way

- How does teleconsultation support values-based health care?

- Has the COVID-19 pandemic prompted any positive changes to service delivery in your area of work?