The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has transformed the treatment of cancer; however, the use of these drugs has led to a group of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in some patients (Das and Johnson, 2019). Many of these events/toxicities are driven by the same mechanisms that produce the drugs' therapeutic effects. These drugs block the inhibitory mechanisms that suppress the body's immune system and protect tissues from an unconstrained immune response (Puzanov et al, 2017). This unique set of toxicities poses complex challenges for those involved in the delivery of ICIs and the management of patients receiving them. The toxicities associated with chemotherapy are short lived and generally resolve when the drug is stopped, whereas irAEs associated with ICIs are completely different and generally require intervention with immunosuppressive agents, usually in the form of corticosteroids. Immunosuppressive therapy is usually administered over several weeks and close monitoring of patients is vital during this time (Brahmer et al, 2018). This is required in order to adequately resolve the toxicity and prevent recurrence.

It is important to highlight that a significant number of patients do not experience any major toxicity from ICIs. Significant irAEs occur in around 20% of patients being treated with monotherapy and up to 60% in combination therapy (Larkin et al, 2019), with around 50% of patients experiencing grade 3 and 4 toxicities, after receiving combination treatment (Hodi et al, 2010).

Immuno-oncology at a regional cancer centre

The authors' regional cancer centre—the Clatterbridge Cancer Centre NHS Foundation Trust (CCC) is a tertiary cancer centre in the north west of England, serving a population of 2.3 million people. The centre delivers around 63 000 systemic anti-cancer treatment (SACT) episodes per year, with ICIs now equating to 10% of the activity, a significant increase from 3.2% of overall SACT delivery in 2017. CCC has been at the forefront of the development of immuno-oncology services. It was the UK's first centralised immuno-oncology service, implemented in October 2018. The service was developed to support the management of the irAEs associated with these novel treatments.

The first approved use of immunotherapy was seen in 2011 in the form of ipilimumab for patients with metastatic melanoma; prior to this, melanoma had been largely untreatable (Batus et al, 2013) and the use of ICIs has significantly changed the prognosis for patients with metastatic melanoma. Since then there has been a surge in the number of ICIs and indications for use made available and approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2022). As of December 2019, the centre facilitated the use of six drugs across 25 indications in eight tumour groups. In addition, there are a further 53 indications currently under review in numerous new tumour sites, including breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and upper GI malignancies.

The increasing availability of ICIs also brings challenges with regard to the administration, provision and support services associated with the delivery of these novel treatments (Puzanov et al, 2017). Recognition and diagnosis of irAEs is largely dependent on where the patient presents (UK Chemotherapy Board, 2018); if a patient attends an emergency department where staff are unfamiliar with ICIs, then the treatment plan can be different from what they would receive at the cancer centre. This can lead to inappropriate management of toxicity and possible unnecessary admissions. The purpose of the immuno-oncology service is to provide specialised guidance and management for patients across the network to ensure the team delivers the best care (CCC, 2022). The challenges of toxicity management include the intensity of patient monitoring throughout the course of the toxicity, which in some cases can be over several months, management of steroid therapy, early detection of deterioration, monitoring of steroid-sparing immunosuppression and management of permanent hormone deficits secondary to immunotherapy. Before this service was set up, management was often delayed and dependent on where the irAEs were identified.

It was apparent very early on in the process that the burden of additional irAE management on tumour site-specific teams was unsustainable, according to an internal (unpublished) report in 2018 by the third author (AO-B). The following areas of the pre-existing model were identified as problematic areas:

- Consultant-led review every treatment cycle—this took up consultant time and led to delays in the clinic

- On-the-day treatment review—this could lead to potential chair blocking as problems were not identified until the day of treatment

- Centralised administration of immunotherapy

- Acute management via an emergency department

- Lack of follow-up

- Hospital admission for the majority of patients with toxicity regardless of grade

- Lack of joined-up care.

Follow-up was reliant on clinical nurse specialist delivery and organised ad hoc.

The regional cancer centre established an immuno-oncology committee early on in the use of ICIs. One of the aims of the committee was to develop and implement standard operating procedures and supporting documentation, along with educational resources for both patients and clinicians. Following on from this, it became apparent that there was a need to establish a toxicity management service delivered by a dedicated nursing team, with clinician oversight from a medical oncologist. The previous model led to multiple issues, including prolonged waiting times for patients. During an audit, several cases of inadequate toxicity recognition and management were identified. This led to unnecessary admissions and delays in appropriate toxicity management. Institutional safeguards are required to ensure swift recognition, assessment and treatment of immunotherapy toxicity (Cole et al, 2019). As the use of ICIs grew, the recognition and acute management of toxicity became more familiar to those involved with its delivery; however, the management following the identification of irAEs, as previously discussed, was somewhat lacking.

The management of acute medical problems is not something that many oncologists are comfortable with, therefore expert advice and support are necessary when dealing with immunotherapy toxicities. IrAEs from ICIs can result in prolonged hospitalisation and high rates of mortality (Reynolds et al, 2018), with the number of patients requiring admission for immunotherapy toxicity significantly increasing in recent years. The delay in such referrals leads to a prolonged length of stay for patients and possible delays in treatment. Reynolds et al (2018) also discussed how there was a critical need for a co-ordinated multidisciplinary approach, comprehensive education and translational research for early detection and intervention of irAEs. Toxicity management often requires input from medical specialties such as dermatology, gastroenterology and cardiology, therefore the immuno-oncology service works in collaboration with these services to ensure the best outcome for patients is achieved.

Aims of the immuno-oncology service

The immuno-oncology service is staffed by a Band 8a lead nurse, a Band 7 advanced nurse practitioner and three Band 6 nurse specialists. The aims and objectives of the service were set out in an internal unpublished report in 2018 by the first author (T-JG). They were to:

- Develop a streamlined service, co-ordinated and managed by a team of experts

- Reduce hospital admission rates

- Develop outpatient management, allowing admission avoidance in certain cases and expediting discharge for those for whom admission is necessary

- Provide a specialist sub-acute toxicity management pathway. The aim of the pathway is to review response to treatment, taper steroids and co-ordinate secondary referrals

- Improve patient experience/quality of life

- Maintain an open dialogue for all involved in the care of patients receiving immunotherapy

- Provide education about immuno-oncology to both healthcare workers and patients.

The immuno-oncology service is multifaceted and covers many elements, including patient education, staff training and education, outpatient pathways and face-to-face nurse-led reviews. However, the majority of the patient management is telephone-based, saving patients travel time and costs. Patients are referred into the service and are managed by the immuno-oncology nursing team, with clinical oversight being provided by the immunotherapy lead nurse and a medical oncology consultant.

An essential part of the service is to provide patient education about these novel treatments, highlighting the significant differences between immunotherapy and chemotherapy, including how to recognise and report potential toxicities. Prior to the development of the service, the melanoma team at CCC highlighted that there were a number of patients who did not report their symptoms via the CCC triage hotline service (Upton, 2016). At the time this was believed to be due to the fact that patients would ‘save’ symptoms until a member of the team, such as the melanoma advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) would contact them. However, the authors believe that, while this is a contributing factor and should be considered when implementing a ‘follow-up’ service, limited patient knowledge and understanding of ICIs significantly impacted on the reporting of symptoms. Phrases such as ‘my treatment might be stopped’ or ‘I thought it was an expected side effect’ were often heard. Patients may fear the anti-tumour effect will be lost if treatment is paused or discontinued due to toxicity; however, studies into outcomes of patients who discontinue treatment due to irAEs show no statistical difference in overall survival (Brahmer et al, 2018). This provides some reassurance that interrupting or stopping treatment does not jeopardise the anti-cancer effect of ICIs. The hope is that, by providing patients with the knowledge and understanding of how ICIs work, they will be more willing to report symptoms, however vague and unfamiliar.

Delayed irAEs have been well documented and can occur weeks after completion of treatment (Pennock et al, 2012). Boudjemaa et al (2018) also discussed how adrenal insufficiency can occur more than one year after completing ICIs. This highlights the need for ongoing monitoring when treatment has been discontinued. A facility for patients to be able to contact the centre and report symptoms should be provided by the cancer centre for a minimum of 12 months post-completion. A suspected or diagnosed irAE should always be closely monitored so that any worsening or relapse is detected. New symptoms or worsening of pre-existing symptoms should be considered and investigated as a possible irAE (Ventola, 2017a; 2017b).

Patients with pre-existing autoimmune disease were excluded from clinical trials due to the concerns of high susceptibility to irAEs. However, there is growing evidence to suggest that ICIs may be safe and effective in this patient group (Haanen et al, 2020). The immuno-oncology service at CCC has provided reassurance to oncologists, who were previous reluctant to treat patients with autoimmune disease, by closely monitoring this patient group during the early phase of treatment.

Literature review

The authors undertook a service evaluation to evaluate the impact of the immuno-oncology service at CCC. As part of this service evaluation it was important to consider any studies or research that had already been undertaken in this area. In order to achieve this, a literature search was carried out using the following: Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, Liverpool John Moores University Library, PubMed, CINAHL, Medline and the BJN's MAG Online Library.

To ensure that the literature search was focused on the research question: ‘What immuno-oncology services currently exist?’ a detailed inclusion criteria was devised (Aveyard, 2013). Search terms included ‘toxicity management’ and ‘immuno-oncology services’. Most of the literature reviewed focused on the incidence of irAEs and gave general guidance as to how these irAEs should be managed.

The impact of immuno-oncology on the delivery of cancer services and acute management services has not been well defined in the literature; however, it has a significant positive impact on treatment outcomes at the authors' centre. However, oncological services at the cancer centre were not equipped to manage the increasing number of patients requiring treatment for not only their malignancy, but also for toxicities. There was a distinct need to develop a service that incorporated the development of immuno-oncology education, acute and subsequent management guidance, collaborative working with acute services and medical specialties, while providing immuno-oncology-specific services and resources. In order for this to be sustainable and to support the growth in the number of new indications for immunotherapy, the need for ongoing investment in the workforce and infrastructure of immuno-oncology services is essential. In order to achieve this sustainability, the service is required to demonstrate its positive impact on oncology services and patient outcomes.

Methodology

The Trust's clinical effectiveness team were contacted and a request was submitted for an electronic list of all patients admitted with suspected irAEs between April 2017 and March 2020. A retrospective review of the electronic patient records was then carried out. As dictated in the nursing Code, all patient cases have been anonymised (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2018). To obtain the relevant information, a data collection tool was developed using Excel. Data collected included the following information:

- Patient number

- Primary cancer diagnosis

- SACT regimen

- Date of last cycle of treatment

- Admission date

- Discharge date

- Length of stay

- Toxicity

- Maximum grading of toxicity

- Previous toxicity

- Date of referral to the immuno-oncology service.

A comparative study of 18 months before and 18 months after the launch of the immuno-oncology service in October 2018 was then undertaken, focusing on the evaluation of three main areas:

- Admission rates due to immune-related adverse events irAEs as a percentage of those treated

- The incidence of Grade 3 and 4 irAEs (compared with trial data)

- Number of bed days occupied due to immunotherapy toxicity.

Ethics

Approval was granted through a robust assessment process set out by the Trust's clinical audit sub-committee. The committee is responsible for ensuring any research is undertaken in accordance with Trust guidance. All data collected were anonymised throughout the process.

Findings

Since April 2017, 1522 patients have commenced ICIs or regimens containing ICIs. Since the launch of the immuno-oncology service in October 2018, 544 patients have been managed by the service. At the time the data collection started the immuno-oncology service was carrying out approximately 500 follow-up calls per month.

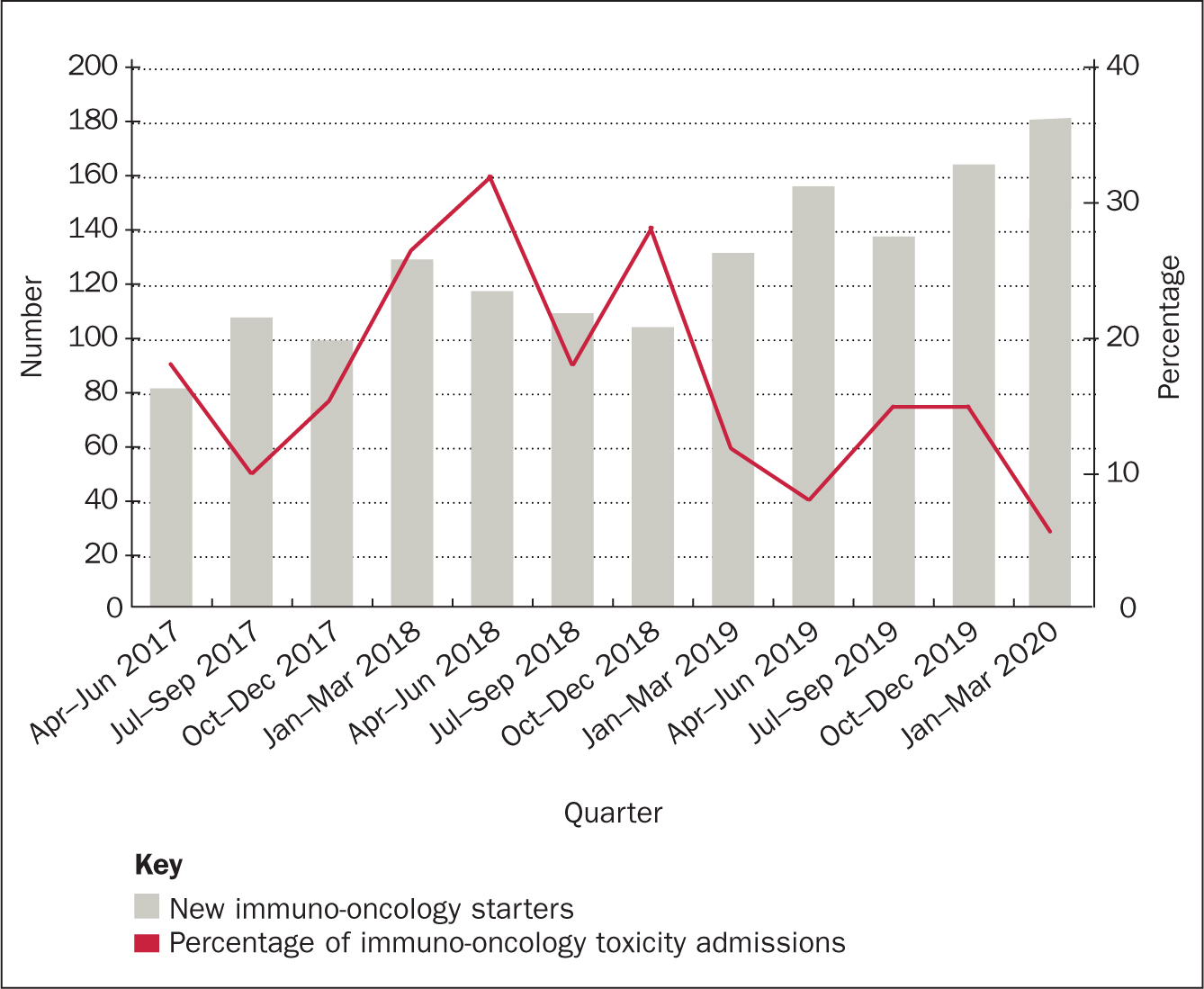

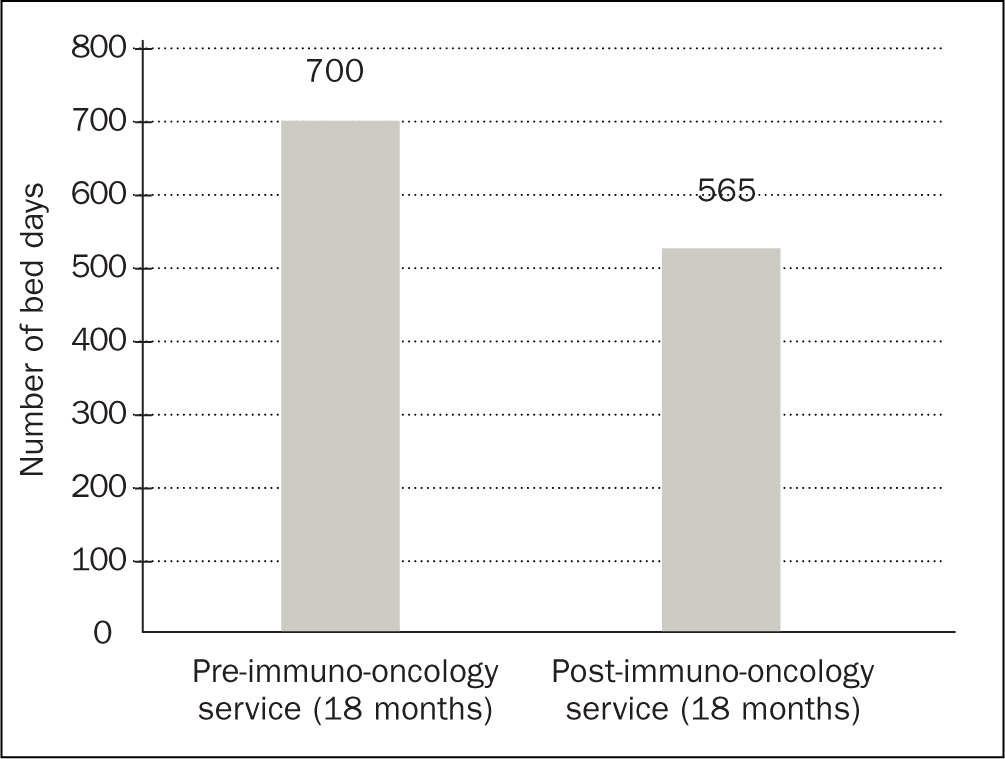

In July 2018, the availability of immunotherapy was rapidly increasing and there had been a significant increase in patients requiring admission for suspected irAEs secondary to immunotherapy. Figures obtained from the clinical effectiveness team at CCC reported an increase of 216% from July 2016–June 2017 to July 2017–June 2018. Increasing outpatient management of irAEs through early identification, regular monitoring and centralised management has facilitated a reduction in the number of patients requiring inpatient management. In the 18 months pre-service there were 648 new starters and 135 admissions due to toxicity (21%); in the 18 months following the launch of the service there were 874 new starters and 115 admissions due to toxicity (13%) (Figure 1). This is a reduction of 38%. The reduction is measured against the admission rates for the 18 months prior to the service and is presented as a percentage of the number of patients commenced on immunotherapy within that time frame. Increasing outpatient management and day-case activity has enabled the immuno-oncology team to reduce admission rates, resulting in an improved patient journey. The immuno-oncology service has developed outpatient pathways for both IV methylprednisolone and infliximab, meaning that patients can attend as a day case and avoid an acute admission. A further audit is required to evaluate day-case activity and the impact with regards to toxicity management. The total number of bed days occupied due to immunotherapy toxicity at CCC has reduced by 19%. This is an overall reduction in 135 bed days, at £460 per day. This equates to a trust saving of £62 100. See Figure 2.

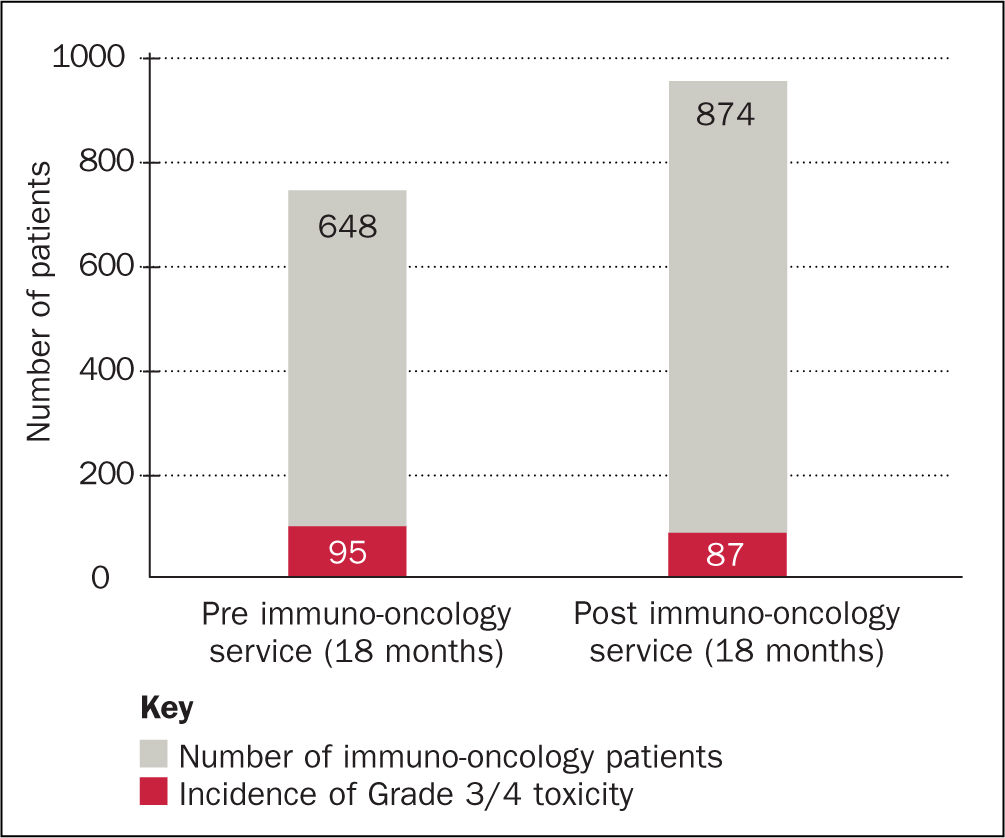

Another area of significant impact by the service is the incidence of Grade 3 and 4 irAEs. A reduction of 32% has been achieved through regular monitoring of Grade 1 and 2 irAEs (see Figure 3). By monitoring mild and moderate toxicity closely, the service has been able to prevent these irAEs developing into severe or life-threatening toxicity. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities can result in long-term complex toxicity management and, in some cases, can be life threatening. Some oncologists are reluctant to recommence immunotherapy once a patient has experienced a Grade 3 or 4 irAE. This can be especially concerning for patients if these develop early on in treatment or before a disease response is evident.

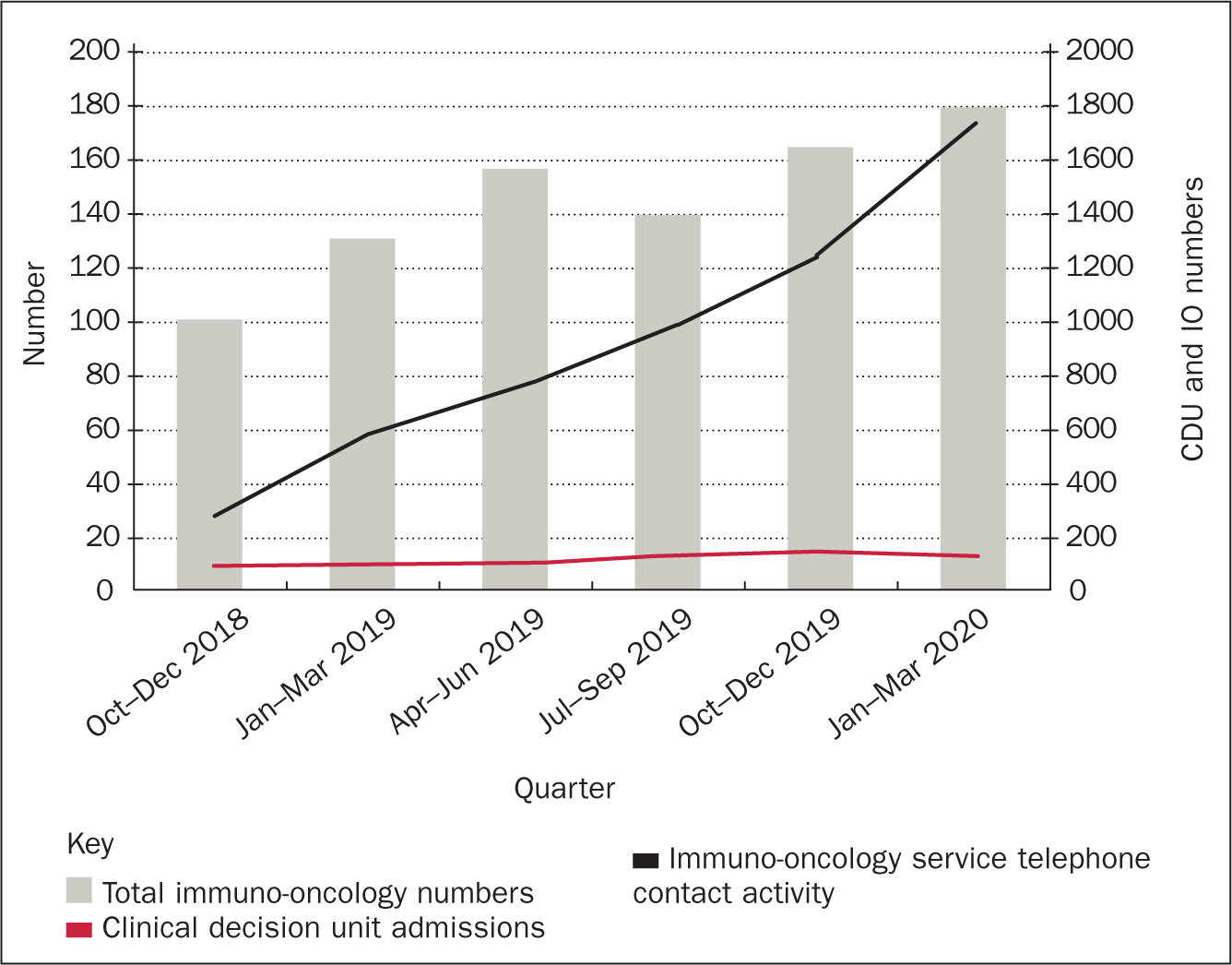

At the time of the service launch the Trust also opened a clinical decision unit (CDU) at the centre, the idea being that all oncological or treatment-related presentations would be admitted via this department. There was concern that the rapid growth in available immunotherapy and its associated toxicities would significantly impact on the workload of the CDU. Although it is not possible to perform a comparison prior to the immuno-oncology service, it is possible to illustrate the activity in comparison to the total number of patients treated with immuno-oncology and the number of follow-up calls undertaken by the immuno-oncology service. The results are illustrated in Figure 4. Although the use of immuno-oncology and the activity of the immuno-oncology follow-up service has grown, the impact on CDU has remained relatively static. The service also provides additional benefits, as listed in Box 1.

Box 1.Benefits of the immuno-oncology service

- Understanding the future of immuno-oncology

- Patient education

- Dedicated immuno-oncology toxicity service with regional reach

- Implementation of current and new regimens

- Management of patient capacity and flow

- Patient advisory service

- Development of immuno-oncology specific resources (website, leaflets, patient app etc)

- Integration of team into relevant medical specialties

- Follow-up provided for all patients with toxicity irrespective of tumour group

- Managed alongside the patient site-specific team

- Acute interface with ward patients and clinical decision unit attenders

- Co-ordination of day-case treatments eg IV methylprednisolone, short synacthen test, infliximab

- High patient satisfaction

- High consultant/team satisfaction and increasing utilisation of the service

Impact of COVID-19

The evaluation of the service was undertaken prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The NHS works has been greatly impacted by the pandemic. Therefore any audit undertaken during this time would not have given a true reflection of the immuno-oncology service and its impact at the Trust. It is important, however, to highlight that the way in which the service works was actually reinforced by the adaptations made by the NHS across the UK. An increase in NICE approvals during the pandemic have increased the availability of immunotherapy, for example in head and neck cancer (NICE, 2022). This has already impacted on immuno-oncology delivery, with approximately 70 new starters each month for the first quarter of 2020. This is an increase of 20 patients per month when compared to the numbers pre-COVID-19.

The service has responded to COVID-19 in the following ways:

- Working from home: the Band 6 team were set up with laptops and mobile phones so they could continue the telephone clinic from their own homes during the initial lockdown

- ANP telephone consultations took place for patients with complex toxicity

- Implementation of a secure email address for patients to use to support the assessment and ongoing review of patients with skin toxicity. This allowed images of a patient's skin to be reviewed by the team without the patient having to attend hospital

- Delivery of medications to patients' home addresses via the hospital pharmacy service

- Changes in the frequency of blood monitoring for patients with stable toxicity

- Recommendation for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis for patients commenced on 60 mg prednisolone and above (or equivalent), or those who have been on >25 mg prednisolone for longer than 6 weeks (as per the CCC steroid-tapering guideline). This was implemented in order to reduce the risk of superadded infections.

Conclusion

The immuno-oncology service at CCC has significantly changed the management of patients receiving treatment with ICIs and regimens including ICIs. Early detection of toxicity and early intervention has resulted in a reduced number of admissions as the team is now able to carry out toxicity treatments for patients as outpatients; helping to promote a better experience and quality of life for patients and reducing pressures on staff. The new service has a flexible approach, facilitates improved quality of life and makes the treatment journey easier for patients. The service has reduced attendances to hospital; toxicity management and blood tests are carried out locally, meaning care is delivered closer to home. The service is supporting patients to carry on working during their toxicity journey and patients are often able to restart treatment once toxicity is resolved.

In order to improve practice with regards to management of patients experiencing complications associated with systemic anti-cancer treatment, it is important that, as healthcare providers, the immuno-oncology team continually assesses and evaluates practice. In order to facilitate future service improvements, a prospective database has been implemented. Identifying patients when they commence immunotherapy will enable the immuno-oncology service to accurately monitor and identify those who develop toxicity. As a result, toxicity management can occur in a more timely and efficient manner, resulting in better patient outcomes (Cole et al, 2019). This will also provide a quick reference for non-oncology providers such as primary care providers, for whom treatment plans are not accessible.

Future projects

Future projects include the implementation of a patient alert system for patients who present to acute trusts/primary healthcare settings with suspected immunotherapy toxicity. Cole et al (2019) discussed how an alert banner on patients' electronic notes can be used in non-oncology settings to identify that a patient has previously received an ICI. This is a concept that would aid the immuno-oncology service at CCC in identifying when patients attend an acute or primary care setting; currently there is no system in place to facilitate this other than reliance on acute oncology teams or GPs to refer into the immuno-oncology service.

Another area of interest to the authors would be to evaluate the impact of the immuno-oncology service on acute trusts within the cancer network. There is a distinct need to maintain strong connections with the acute oncology teams based at district general hospitals. As well as carrying out audit work in this area, it is vital that the immuno-oncology service continues to provide ongoing education and support for staff in all areas involved in the support and management of oncology patients. It is important to discover how the work already undertaken by the immuno-oncology service impacts on acute services to support better patient outcomes.

KEY POINTS

- As the pressure on hospitals and cancer services continue to increase due to the growing number of patients requiring treatment and the availability of novel treatments, it is necessary to identify new and innovative ways of working

- It is vital that oncology services develop pathways to identify and manage the associated immune-related adverse events

- The discussion and evaluation of established immuno-oncology services may help and enable other centres to develop their own immuno-oncology services

CPD reflective questions

- Consider the benefits of a toxicity management service for other types of systemic anti-cancer treatment

- Reflect on the factors that highlight the need for specialist immuno-oncology toxicity management

- Consider how nurse-led follow up services can benefit other areas of cancer care