Advanced practice in nursing has been described as a means of expanding nursing care that enhances patient safety and improves the quality of patient care (Zarnitz and Malone, 2006; Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), 2013a; Boyle et al, 2014). The introduction of the European Union Working Time Directive reduced working hours for junior doctors, changed medical training, and increased the demand for non-medical staff to undertake assisting roles intraoperatively. These directives recommended that nurses and allied health professionals undertake expanded practice roles, including the registered nurse first assistant (RNFA) (Al-Hashemi, 2007; Timpany and McAleavy, 2010; Quick et al, 2014; Abraham et al, 2016; Simpson, 2017).

Background

An RNFA is a non-medical practitioner who performs surgical interventions during surgery and provides medical care to the perioperative patient under the supervision of a consultant surgeon (AORN, 2013a; Quick and Hall, 2014; Quick et al, 2014; Hains et al, 2017a). A diverse number of titles identify the role within international literature. These include: perioperative nurse surgeon, assistant, non-medical surgical assistant, registered nurse first assistant, registered nurse first surgical assistant, surgical care practitioner and expanded scrub practitioner (Quick et al, 2014; Quick et al, 2015; Abraham et al, 2016; Hains et al, 2017a). In some Nordic countries, scrub nurses had fulfilled the responsibilities of the first assistant since the Second World War, enabling cost-effective highly professional perioperative care (Silén-Lipponen, 2005).

The scope of practice of an RNFA is extended over the perioperative care phases and incorporates both the role of the perioperative nurse and that of the medical practitioner (Zarnitz and Malone, 2006; Quick and Hall, 2014; Hains et al, 2017a; Simpson, 2017). Responsibilities of the RNFA pre-operatively may include assessment and preparation of the patient for surgery (Zarnitz and Malone, 2006; Hains et al, 2017a; Simpson, 2017). Intra-operatively the RNFA is required to have manual dexterity, microbiological safety, technical knowledge of the procedure, and good knowledge of the anatomy to handle tissues, to manipulate organs for exposure and to assist with haemostasis safely under the surgeon's supervision (Zarnitz and Malone, 2006; AORN, 2013b; Quick and Hall, 2014; Simpson, 2017). Good knowledge of anatomy ensures that the assistant is familiar with the structures underlying the operative field, which in turn helps to diminish risks of injury to the patient (Quick and Hall, 2014). Postoperative responsibilities include: wound care management, pain management and discharge planning (Zarnitz and Malone, 2006; Bryant, 2010; Simpson, 2017). Silén-Lipponen (2005) and Aholaakko (2018) described responsibilities required within the role of the RNFA. The role enables nurses to become expert practitioners using nursing skills to provide consistent holistic care to patients (Al-Hashemi, 2007; Abraham et al, 2016). Before practising as an RNFA, nurses are required to successfully complete an academic programme with surgical training (Zarnitz and Malone, 2006; Quick and Hall, 2014; Quick et al, 2014).

Aim

To appraise existing evidence on the RNFA role within the perioperative setting

Methods

Search strategy

A literature search was undertaken during September–December 2017. Initially this was limited to the following databases: Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, Web of Science and PubMed. However, due to the limited literature acquired from these databases, additional databases such as Science Direct, Scopus, Wiley Online Library, and SAGE were also searched. Inclusion criteria were:

Exclusion criteria were:

The review question was formulated in the ‘PEO’ format:

Search terms used were: registered nurse first assistant (RNFA), surgical first assistant, non-medical surgical assistant (NMSA), perioperative nurse surgeon's assistant (PNSA), surgical care practitioner, advanced scrub practitioner, role, impact, influence, responsibility.

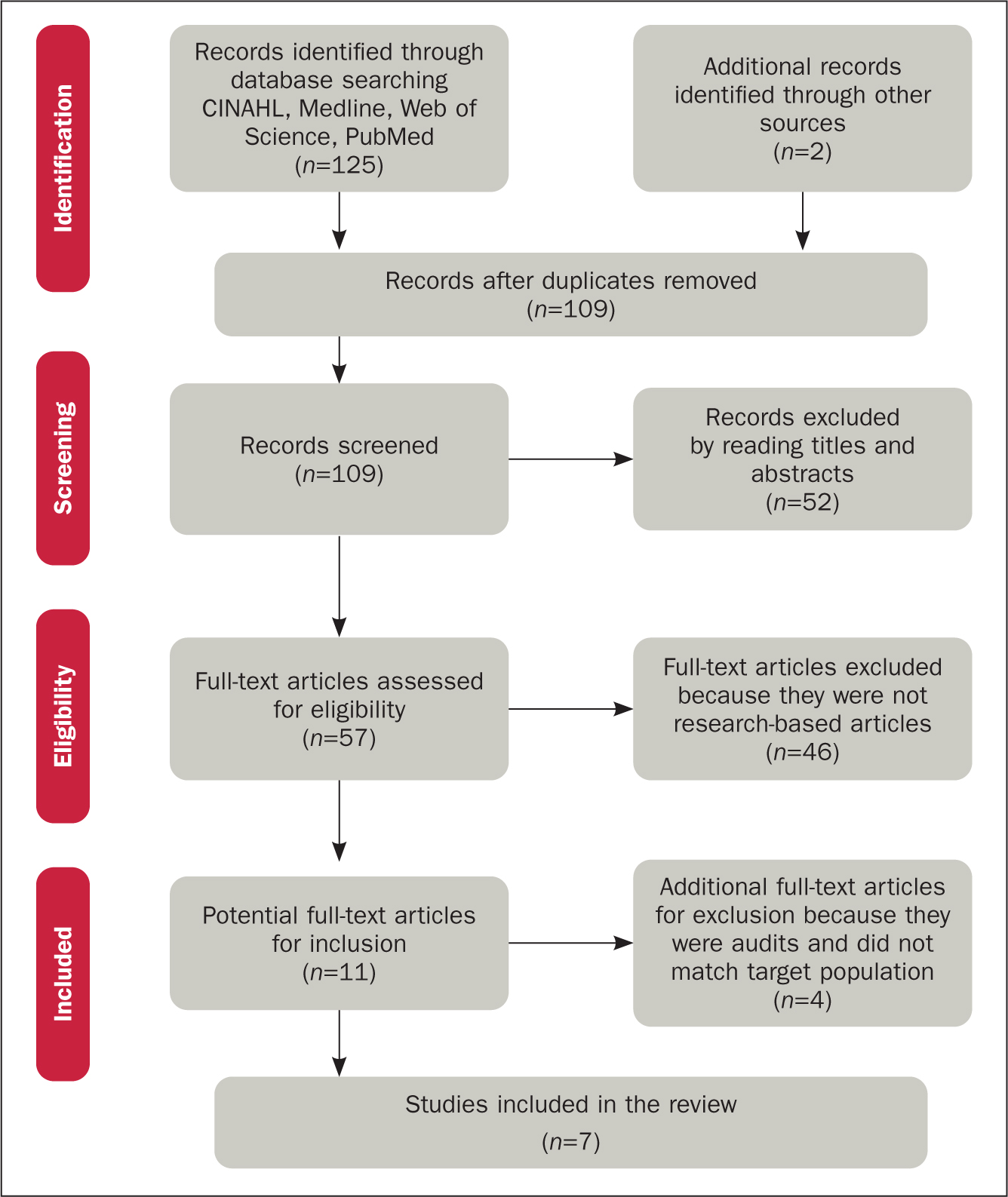

The search initially yielded 125 results, which were narrowed down as in Figure 1, leaving 7 articles for appraisal and analysis. All studies were undertaken in the perioperative setting.

Appraisal and analysis

Crowe's critical appraisal tool (CCAT) (Crowe, 2013) was the tool used to critically appraise the evidence in this review (Table 1). Characteristics of the research articles are presented in Table 2. An individual evidence summary table was then devised to extract the data under headings.

| Article | Appraisal score |

|---|---|

| Buch et al, 2008 | 83% |

| Quick, 2013 | 84% |

| Lynn and Brownie, 2015 | 80% |

| Hains et al, 2016 | 88% |

| Smith et al, 2016 | 78% |

| Hains et al, 2017b | 85% |

| Hepps et al, 2017 | 75% |

|

|

Following review of seven articles, thematic analysis was used to group the themes within the literature. This involved continuously reading the studies to identify common themes.

Themes identified

From the thematic analysis three common themes were identified: knowledge advancement, expanding roles in the perioperative setting and surgical contribution.

Advancing knowledge

Continuous learning is required for RNFA practitioners in developing skills to assist, mentor and teach colleagues within the perioperative setting (Buch et al, 2008; Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Hains et al, 2016; Smith et al, 2016; Hains et al, 2017b; Hepp et al, 2017). Mentoring both nursing and medical staff within the perioperative setting assists in alleviating skill-mix issues by providing a source of knowledge for scrub nurses and medical surgical assistants.

Perioperative nurses benefit from leadership skills of the RNFA (Quick, 2013; Smith et al, 2016). In the work by Smith et al (2016), 87% of perioperative staff believed that RNFA roles have a high or moderately high impact on effective leadership and mentorship. The introduction of the RNFA role within the perioperative practice was beneficial to both medical and nursing staff education and training (Buch et al, 2008; Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Smith et al, 2016; Hains et al, 2016; Hepp, 2017). The RNFA contributes to the development of medical staff within the perioperative setting by providing an opportunity for surgical trainees to gain additional surgical exposure. Surgeons acknowledged that the RNFA was able to teach junior doctors basic surgical skills such as suturing and knotting, while providing them with an opportunity to obtain surgical exposure during their surgical training (Quick, 2013). In the survey by Buch et al (2008), 57.1% of first year medical staff within the perioperative setting perceived the RNFA as beneficial to their clinical education, in comparison with only 16.7% of senior medical staff.

RNFAs within surgical teams provide an opportunity for successful interprofessional relationships to develop by decreasing medical staff workload, thereby enabling them to access educational opportunities throughout their rotation (Buch et al, 2008; Quick, 2013). Smith et al (2016) found 98% of perioperative nurses surveyed agreed that they like having a RNFA within the theatre.

The RNFA is an additional support for novice perioperative nurses in advancing their knowledge on specific case instruments required and an overview of surgeon preferences. The RNFA is recognised as a great source of knowledge within the operating room due to their understanding of each surgeon's way of operating (Quick, 2013; Hepp et al, 2017).

Expanding roles in the perioperative setting

The RNFA role is acknowledged to facilitate meaningful engagement in clinical practice while expanding professional development (Lynn and Brownie, 2015). RNFAs and perioperative nurses recognise the need for continuous education as beneficial to their personal and professional growth in undertaking their work (Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Hains et al, 2016). Education has a significant effect on the ability of the RNFA to perform complex tasks (Hains et al, 2017b). Surgeons and perioperative nurses within all the studies argued that undertaking an RNFA programme provides the intended practitioner with skills and knowledge to undertake advanced practice tasks safely (Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Smith, 2016; Hains et al, 2016; Hains et al, 2017b; Hepp et al, 2017). Some perioperative nurses are undertaking advance practice tasks without the appropriate education and training. However, the RNFA as an advanced and expanded practice role, without appropriate training and support, could impinge on patient safety. A well-structured approach to learning may lead to an expansion of clinical practice enabling them to undertake new challenges within the perioperative setting. To expand services within care provision, surgeons motivate nurses to undertake the RNFA programmes to advance their knowledge and skills within the perioperative practices (Lynn and Brownie, 2015).

Autonomy and practice is supported or constrained by a number of legislation statutes, depending on the country in which the nurse works (Hains et al, 2017b). RNFA training is not solely based on gaining accreditation through RNFA graduate programmes. The RNFA must acquire skills from a supervising surgeon (Hepp et al, 2017).

RNFAs contribute to perioperative efficiency, assisting with provision of services to surgical patients (Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Hains et al, 2016; Smith et al, 2016; Hepp et al, 2017) Surgeons found RNFAs to be very competent practitioners who provide preoperative care to patients as efficiently as their medically trained colleagues (Quick, 2013; Smith et al, 2016). Surgeons view RNFAs' pre-existing nursing skills and professional attributes as integral to the role due to their ability to improve the patient experience within the perioperative setting (Quick, 2013). The addition of the RNFA to the surgical team encourages a cohesive approach, which in turn improves patient care by ensuring patient understanding and compliance. Patients perceive RNFAs as a great addition to the healthcare system due to their abilities to alleviate patients' concerns and ensure patient compliance to care (Hepp et al, 2017). Involvement of the RNFA within the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of perioperative care ensures the delivery of high-quality, safe care for surgical patients (Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Smith et al, 2016; Hepp et al, 2017).

Surgical contribution

The RNFA contributes significantly to the provision of care within all phases of perioperative care. They contribute to theatre efficiency by carrying out tasks (such as exposure, dissection and haemostasis), reducing the operating time (Hains et al, 2016). Tasks undertaken by the RNFA can considerably increase surgical capacity within an allocated theatre session, decrease waiting time and maximise the number of patients on the surgical list (Hains et al, 2016; Hepp et al, 2017). Additional tasks (closing incision, room cleaning) assist the multidisciplinary team in improving patient care within the operating room (Hepp et al, 2017).

Inclusion of the RNFA on the perioperative multidisciplinary team contributes positively to the care of patients (Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Hains et al, 2016; Smith et al, 2016; Hepp et al, 2017). RNFAs are a helpful resource, assisting the multidisciplinary team in delivering safe and effective patient care eg positioning, setting-up of operating room, problem-solving with equipment and wound management (Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Hains et al, 2016; Smith et al, 2016; Hepp et al, 2017).

Perioperative nurses acknowledged that the RNFA supports the multidisciplinary team by using leadership skills in increasing team efficiency and alleviating the effect of inadequate staffing, while contributing to the smoother running of the operating list (Lynn and Brownie, 2015). The RNFA assists perioperative nurses by undertaking certain nursing duties such as setting up the scrub nurse by finding and opening the necessary equipment required for the case. They enhance and facilitate interprofessional communication through their knowledge of surgeons' preferences (Quick, 2013; Lynn and Brownie, 2015; Smith et al, 2016; Hepp et al, 2017). Having a consistent RNFA within the perioperative department was recognised by both perioperative nurses and surgeons as enhancing the perioperative team (Quick, 2013; Hepp et al, 2017).

Limitations and recommendations for future research

Currently the role of the RNFA is not clearly defined and is used interchangeably with that of the physician assistant. There is little literature on the role of the RNFA due to its recent emergence in the healthcare sector in only some countries worldwide. Further research is required to clarify the multifaceted role and scope of practice of the RNFA as it currently varies within different hospitals. A research evaluation from perioperative nurses, surgeons and patients may benefit the role.

Conclusion

The scope of the RNFA role extends beyond the traditional limitations of the perioperative nurse's scope of practice. It is evident that the extended clinical role assists the perioperative team in the completion of nursing and other clinical tasks that were originally only associated with medical practitioners. It has been established that the members of the perioperative team view the introduction of such an advanced and expanded practice role within the perioperative setting as beneficial to the delivery of safe care to surgical patients and as a means of improving efficiency and reducing costs.

The RNFA scope of practice covers all phases of perioperative care and their use within the operating room can increase efficiency, thereby reducing operating time. Continuous education and training has been identified as crucial to the role of the RNFA. Evidence clearly demonstrates that RNFA without the required skills and knowledge may hinder patient safety. When implementing the RNFA role into practice, institutions must ensure that eligible perioperative nurses acquire the necessary knowledge and training. This would ensure that only competent RNFAs are practising within the perioperative setting. The RNFA role scope of practice goes beyond the boundaries of traditional perioperative nursing care. Therefore, hospital administrators and managers who currently use or seek to introduce the RNFA role should develop policies and guidelines clearly defining the areas of perioperative practice in which the RNFA scope would extend. Such action could help define the RNFA role within the perioperative setting, ensuring that the RNFA role delineation is clear to all members of the multidisciplinary team. This review has identified that training of perioperative staff in undertaking both medical and nursing tasks contributes to the development of perioperative staff, quality of care and productivity within the perioperative setting.