A large part of the workload for many specialist urology nursing teams is managing and supporting patients with urinary tract infections (UTIs), or symptoms of UTIs with no confirmed infection. UTIs represent a common problem with previous estimates suggesting 150 million cases reported worldwide each year (Global Burden of Disease Study Collaborators, 2016). This has a significant impact on patients' physical, psychological, social, and economic health, while also impacting on healthcare budgets (Harding, et al, 2019). The ratio of female to male UTI patients within the service discussed in this article is approximately 80:20, which is in line with that reported elsewhere (McGuinness et al, 2018).

There are many possible factors why occurrence in females is higher than in males: the female urethra being closer to the anus and shorter in length, triggers such as sexual intercourse or urogenital ageing, pelvic organ prolapse, and urinary incontinence (Aydin et al, 2015). Recurrent infections in men are mainly associated with increasing age and enlargement of the prostate, resulting in a post-void residual within the urinary bladder, which can then stagnate, leading to the proliferation of organisms (Schaeffer and Nicolle, 2016). However, clinically it is not always apparent what the cause of infection might be, and it is necessary to simply start with symptoms in the first instance.

A UTI is defined as the presence of bacteria in one or more parts of the urinary tract, with invasion of tissue and onset of symptoms (Lüthje and Brauner, 2016). Box 1 provides a list of possible symptoms. Historically, a genuine UTI has been defined as a count greater than 100 000 (105) colony-forming units of the same organism per millilitre of urine (cfu/ml). These figures originated decades ago from work by Kass et al (1956) using organisms easily cultured in laboratories at that time. Advances have been made since, with evidence of symptoms at lower levels, suggesting a review is needed (Harding et al, 2019). Escherichia coli (E. coli), a bacterium normally found in the gastrointestinal tract, is the most common cause of UTIs. Other common causes are Klebsiella, Enterococcus and Proteus species, but the list is extensive (Walsh and Collyns, 2017).

Box 1.Common symptoms of urinary tract infections

- Dysuria – painful voiding

- Urinary frequency

- Suprapubic pain/tenderness

- Nocturia

- Urgency

- Urge incontinence

- Strangury – further pain after voiding

- Offensive smelling urine

- ‘Bearing down’ – heaviness in the pelvis

- General malaise

- History of fever, rigours, and loin pain – infection could be ascending to kidneys

- In men a urinary tract infection can cause an acute retention

- Presentation in the elderly: confusion, worsening mobility, malaise

Source: Osamwonyi and Foley, 2017

Recurrent UTIs are defined as two episodes of confirmed infection within a 6-month period, or three episodes within 12 months (Aydin et al, 2015). Reports suggest that 30–44% of women will have a likely recurrence within 3 months of being treated for a UTI (Osamwonyi and Foley, 2017). This can be thought of as a relapse, defined as a UTI caused by the same microorganism after treatment, or reinfection by a new microorganism or the previous microorganism following treatment and a negative culture (Reynard et al, 2019)

The duration of treatment provided varies considerably depending on whether the UTI is considered complicated or uncomplicated. ‘Uncomplicated’ typically refers to lower urinary tract symptoms in women with a normal, unobstructed genitourinary tract, whereas ‘complicated’ is used when there is either a structural or functional abnormality, such as having a catheter in situ, presence of stones, incomplete bladder emptying, male, impaired immunity or pregnancy (Osamwonyi and Foley, 2017). An uncomplicated UTI in a female patient would generally receive 3-7 days of antibiotics with those cases considered complicated or in males receiving 7-10 days (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2018).

The challenge for many specialist urology teams is how to standardise management of recurrent UTIs. The aim of this discussion is therefore to review the available evidence and current practices, to provide a standard approach across the team where practical. Thereby reducing variation in approaches, which could impact on outcomes for patients. An important limitation that has become apparent is the lack of definitive research in this area, often with small patient numbers, a gender bias towards female patients, and lack of transferability or relevance to wider patient groups. It is also acknowledged in practice that there are individual differences in how patients respond to treatment, and inconsistencies in staff treatment choice and duration, coupled with challenges such as patient compliance, cost and being a non-prescribing team.

The following case reports therefore aim to illustrate some of the aforementioned, while drawing on evidence-based research and local experience in practice. All patient names have been changed for confidentiality.

Case study one

Presentation

Jim is a 52-year-old farmer referred to the specialist urology team by his GP for recurrent UTIs. Jim has had seven confirmed E. coli UTIs in the past 8 months, with symptoms of frequency, cloudy/smelly urine, and a stinging sensation within the penis during and after micturition. He has received several 7-day courses of either nitrofurantoin or trimethoprim, but the symptoms return within days of stopping the antibiotics.

Assessment

Box 2 provides an outline of initial assessment tools and questions that may be considered useful. When managing recurrent UTIs the practitioner needs to consider in both male and female patients the possibility of bladder cancer, underactive bladder, urethral strictures and bladder stones, and in males an enlarged prostate, which could be either benign or cancerous (Temiz and Cavdar, 2018).

Box 2.Initial assessment questions/tool

- Physical examination

- Male: check foreskin is retractable/clean

- Female: check for cystocele/rectocele, vaginal tissue atrophy

- General lumps or skin damage

- Perform a urinary flow: checking for urethral stricture, enlarged prostate and post-void residual of urine >200 ml

- Frequency/volume chart: is the patient voiding regularly (more than 4 voids daily)?

- Sexual health screen: to rule out any sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), candida infection, or bacterial vaginosis (BV)

- Review symptoms: listen carefully to symptoms or triggers

- Review urine results: does the organism vary or is it a repeat offender?

- Review previous treatments: may need to contact GP for prescribed antibiotic history

- Check fluid intake: keep urine dilute and less irritant, check type of fluid for irritants such as alcohol

- Check bowel history: constipation can affect bladder function and provide reservoir for E. coli

- Consider past medical history: Diabetes – prone to infections; previous prostatitis – to rule out; multiple sclerosis – poor bladder function/neurogenic bladder; enlarged prostate – poor flow; check urinary post-void residual, potential reservoir for bacteria; surgical history – any gynaecological surgery or childbirth complications

- Regular periods – menopause, think topical vaginal oestrogen and probiotics

- Change in vaginal secretions: strong fishy smell, grey/white/thin/watery secretions = check for BV

Jim's urine results were checked and E. coli was confirmed as the main offender. A post-void residual volume was obtained and found to be less than 50 ml. His sexual health was also discussed with no indication for further testing required. There were no constipation issues and Jim was encouraged to increase his fluids, particularly due to the active nature of his job.

A diagnostic flexible cystoscopy was requested, which showed no sign of bladder cancer or stones but some mild bladder wall inflammation was identified, likely due to the frequent infections.

Treatment plan

While waiting for the cystoscopy it was suggested to the GP that an extended course, rather than a standard course, of antibiotics could be tried. This time Jim undertook a 2-week course of nitrofurantoin modified release 100 mg twice daily. This initially kept Jim clear of symptoms, which unfortunately returned within 2 weeks of finishing the antibiotics. Local guidance on extended use of antibiotics is led by the microbiology team who suggest 2 weeks for females and 4 weeks for males. However, although it is an extremely useful antibiotic, nitrofurantoin should be avoided in repeated or long-term use (>6 months) due to the risk of potential respiratory complications and fibrosing lung disease (Osamwonyi and Foley, 2017). The British National Formulary (Joint Formulary Committee, 2023) also provides guidance on how to use with appropriate caution (taking into account estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)).

Jim was then contacted by telephone at 8 weeks after his initial assessment. He was experiencing ongoing symptoms again and on another course of antibiotics. At this point it was suggested that Jim try D-mannose, beginning on the last day of his antibiotic prescription. D-mannose is a natural sugar, and its use works on the same principle as cranberry extract. Bacteria are said to attach to the D-mannose molecule rather than to the bladder wall, being excreted within the urine (Feng et al, 2018). There are several studies supporting the use of D-mannose, particularly with E. coli UTIs, and it is now part of the NICE (2018) guidelines.

In practice D-mannose does seem to make a difference for some patients, particularly in improving symptoms so that they are at least more tolerable as opposed to cured completely. It is available from health food shops in tablet, powder, and effervescent preparations, at a cost to the patient of around £20 for a month's supply. Dose recommendations vary from different manufacturers with preparations varying in strength. A general recommendation might be 1 g twice daily for maintenance, which then increases to 1 g four times daily for 5 days when patients begin to experience symptoms. D-mannose is reported to be more effective with slightly alkaline urine, therefore the juice of half a fresh lemon squeezed into water daily is also recommended (Kumar et al, 2012). An important caveat to give patients is that should their symptoms worsen, they will still need to seek medical advice and the use of antibiotics may still be warranted.

Outcomes

Having been given the advice regarding D-mannose and lemon juice, Jim was followed up at a further 8-week interval and was found to have been infection free. Jim was again followed up in another 3 months and found to be still UTI free and therefore discharged from the team's care.

Case study two

Presentation

Sue is a 47-year-old office worker referred to the nurse-led team by a consultant urologist due to recurrent UTIs with resistance to multiple antibiotics. Sue had recently moved to the area, having tried various treatments over the past 2 years, specifically intravesical Cystistat, iAluRil and gentamicin. Sue also uses intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC) four times daily for an underactive bladder. She had been on a prophylactic dose of nitrofurantoin immediate release 50 mg daily for over 18 months, as this was the treatment that seemed to be most effective, although she often had breakthrough UTIs. Again, due to the long-term risks of nitrofurantoin the team were keen to discontinue this and be less reliant on antibiotics to manage her infections.

Prophylactic low-dose antibiotic therapy is currently standard practice and supported by NICE (2018), shown to decrease episodes of recurrent UTIs but potentially increasing adverse effects such as vaginal and oral candida infection, gastrointestinal symptoms, and the spread of antibiotic resistance (Tache et al, 2022). Box 3 provides suggested antibiotic dosing regimens. Another option for female patients who are sexually active can be the use of postcoital antibiotics because the use of spermicidal contraceptives or having a new sexual partner can increase the risk of UTIs (Osamwonyi and Foley, 2017).

Box 3.Antibiotic dosage for prophylactic and postcoital regimens

- Nitrofurantoin 50–100 mg at night or 100 mg for 1 dose following exposure to a trigger

- Trimethoprim 100 mg at night or 200 mg for 1 dose following exposure to a trigger

- Cefalexin 125 mg at night or 500 mg for 1 dose following exposure to a trigger

Source: Joint Formulary Committee, 2023

Assessment

Before referral, the urology team had already arranged for a cystoscopy, which showed bladder wall inflammation but no other signs of concern to account for symptoms. A renal tract ultrasound scan was normal in its findings. The initial assessment (as outlined in Box 2) highlighted key symptoms and treatments tried previously.

Sue had previously had some E. coli and Klebsiella-positive urine results, but at other times urine tests would come back with no growth. However, she remained symptomatic with frequency, urgency, urinary leakage, and lower abdominal and back pain. Due to recurrent UTIs, Sue's ISC technique and catheter were reviewed. Sue was also struggling with constipation, where advice to consume a glass of prune juice daily and try senna tablets was given with follow-up. Sue was hydrating well, the sexual health screen highlighted vaginal candida, which was treated, and Sue reported her periods to be erratic and felt she was perimenopausal.

A vaginal examination presented some pale pearly white vaginal tissue, suggestive of vaginal atrophy. Therefore, the GP was asked to prescribe some topical oestrogen with the aim of reducing vaginal dryness and decreasing the vaginal pH, so it is more acidic, improving vaginal flora and numbers of ‘protective’ lactobacilli (Walsh and Collyns, 2017). Vaginal flora would normally play an important part in the prevention of UTIs in premenopausal women, with lactobacilli excluding other uropathogens by competitive exclusion and maintaining vaginal pH (Beerepoot and Geerlings, 2016). The body of research into probiotics (with certain types of lactobacilli) in recurrent UTI management is growing, but inconclusive with large-scale clinical trials needed to guide probiotic use in recurrent UTI management (Gupta et al, 2017). Patients have reported that taking probiotics can be a positive way of getting involved in their own care. They are deemed safe and are something patients can commence without waiting for a prescription, monitoring themselves for any improvement, which supports feeling that they are actively trying to help themselves, particularly if the patient has had multiple courses of antibiotics, as in Sue's case.

Sue has tried intravesical treatments, such as sodium hyaluronate 40 mg (Cystistat), combination sodium hyaluronate 800 mg and sodium chondroitin sulphate 1 g (iAluRil), and intravesical gentamicin 80 mg. The idea behind the first two treatments is to repair the bladder lining (glycosaminoglycan or GAG layer), waterproofing the bladder wall against irritants and bacteria (De Vita and Giordano, 2012). There is evidence that supports their use, but mainly with recurrent UTIs in females, and these studies had small participant numbers making conclusive evidence difficult to judge. In local clinical practice there is some success with female patients and instillations, but generally the benefit has not been seen in men. Reddy and Zimmern (2022) conducted a systematic review into the intravesical treatments of gentamicin 80 mg, sodium hyaluronate 40 mg and sodium hyaluronate 800 mg with sodium chondroitin sulphate 1 g, concluding there was evidence of their efficacy in treating recurrent UTIs in women when antibiotic use has been unsuccessful.

Sue has previously tried gentamicin 80 mg diluted with 20 ml sodium chloride 0.9%, instilled into the bladder via self-catheterisation. This is then held for at least 1 hour, before being either voided or drained (Cox et al, 2017). Clinically this has been found to be a useful treatment for gentamicin-sensitive organisms because it is not absorbed through the bladder wall, has no systemic effect, and the effect on renal function is considered very low. However, in local clinical practice intravesical gentamicin has been shown to work best in more complex cases, such as in patients with a neobladder or urostomy. The team has found treatment can become ineffective after a few months when used in more straightforward recurrent UTI patients with no structural changes. Therefore, this is a good approach to have in reserve when other treatments have not worked.

Treatment plan

Due to little success with previous treatments, Sue was started on methenamine hippurate. The standard dose is 1 g twice daily, but given Sue's ISC regimen, 1 g three times daily was chosen, as recommended for patients with catheters (Joint Formulary Committee, 2023). Methenamine hippurate is not an antibiotic, but rather works like an antiseptic. If the urine is acidic enough, methenamine will turn into formaldehyde to kill bacteria (Heltveit-Olsen et al, 2022). Sue has normal renal and liver function and was given the advice these should be checked at intervals. Sue was advised to stop the methenamine hippurate if she experienced nausea or vomiting, re-starting after 4 weeks (Malone-Lee, 2021).

The overuse of antibiotics has seen a rise in microorganism resistance to commonly used antibiotics worldwide (McGuinness et al, 2018) making methenamine hippurate an interesting option to avoid overuse of antibiotics.

Latest research (Malone-Lee, 2021) has encouraged re-evaluation of practice due to current thinking on imbedded chronic bladder infections and treatment methods. Following this, methenamine hippurate has begun to be used more widely in local practice with positive initial results seen while data are collected for auditing. The ALTAR (ALternatives To prophylactic Antibiotics for the treatment of Recurrent urinary tract infection in women) study (Harding et al, 2022) has also been recently published, supporting methenamine hippurate as a safe option to use, but raising the question of whether it is a cost-effective treatment in the long term (Harding et al, 2022). Based on NHS indicative pricing information (Joint Formulary Committee, 2023), a one-off 1-week's treatment supply of modified release nitrofurantoin 100 mg is £9.50, whereas ongoing use of methenamine hippurate comes in at £19.74 per month. With support from the urology consultants, it has been beneficial for methenamine hippurate to be added to the local formulary to help increase prescribing confidence. The recommendation being to start with a 2-week prescription of antibiotics followed by methenamine hippurate (Malone-Lee, 2021). This is because the methenamine hippurate can cause dysuria due to being an acidic drug capable of irritating an already inflamed urinary tract, and so reducing inflammation first with antibiotics helps minimise potential for this (Malone-Lee, 2021). It tends to be provided on a repeat prescription with the aim of weaning off antibiotics first followed by the methenamine hippurate, which could be up to a year later. The ALTAR study (Harding et al, 2022) also supported the argument that trying to acidify the urine with cranberry extract or vitamin C was probably not achievable. However, contrary to this, manufacturers currently do advise that if results are not achieved with methenamine hippurate alone, then either vitamin C or cranberry extract may be useful to acidify the urine and help boost treatment. It is however worth considering the risk of kidney stone formation with vitamin C supplements (Ormanji et al, 2020). Cranberry extract can also react with warfarin, making dosing of warfarin difficult to manage (Soyata et al, 2020).

At 6 weeks into methenamine hippurate treatment Sue was on antibiotics again, but methenamine hippurate does need time to have a cumulative effect. Sue has only had one UTI since starting methenamine hippurate, which is an improvement in her symptoms and it is important to recognise small wins. However due to Sue's long history of recurrent UTIs and multiple treatments tried, she has been referred into the joint microbiology and bladder nurse specialist clinic.

Outcome

Sue has discontinued prophylactic nitrofurantoin and is now just being prescribed antibiotics for breakthrough infections as they occur. Continued use of methenamine hippurate has resulted in the occurrence of fewer recurrent UTIs for her, suggesting steady progress in managing her condition. The next step will be for Sue to attend the joint nurse and microbiology clinic to see if any further review would be of added benefit for her.

Discussion

The reliability of the well-used tool of testing urine by microbiology, culture and sensitivity (MC&S) has been in question lately (Malone-Lee, 2021). Kass (1956) never claimed to define a diagnostic threshold, but from his work, 105cfu/ml was adopted as the threshold between no UTI and a confirmed UTI. Clinically many symptomatic patients present with a urine sample deemed negative, subsequently struggling to obtain treatment. In practice, if a urine sample does not support presence of infection, then advice should ideally be to treat based on symptoms and history – of course, considering antibiotic side effects, resistance, cost, and the patient engagement with conservative measures listed in Box 4.

Box 4.Self-help steps (advice for patients)

- Hydrate with 2 litres or more daily – aim for dilute urine, as less irritant

- Avoid/treat constipation – avoid a build-up of possible E. coli

- Change loose-fitting cotton underwear daily – avoid irritation, sweating and build-up of E. coli spores

- Void and wash after sex – sex can be a trigger, aim to eliminate bacteria

- Use non-scented soap or soap substitute – avoid irritation and protect natural acidic vaginal pH

- Use non-spermicide lubrication and contraceptives – spermicides are alkaline and can change vaginal flora

- Wash sex toys with warm soapy water or follow manufacturer's cleaning instructions – avoid transmission of bacteria

- Wipe from front to back – reduce spread of bowel flora to the urethra

- Avoid luffa (loofah) sponges or reusable sponges – could harbour bacteria

- Use tampons rather than sanitary towels – towels/pads can create an ideal environment for bacteria near the urethra

Aggarwal and Lotfollahzadeh, 2022

Both Jim and Sue have been helped by perhaps unconventional treatments after standard care had not achieved the results sought after: D-mannose with the patient purchasing their own supply, and methenamine hippurate as until recently this was not regularly used locally, with the nursing team now encouraging its use both in primary and secondary care.

Another beneficial approach has been the introduction of a joint microbiology and bladder nurse specialist clinic, providing an example of multidisciplinary working, which has been invaluable in improving advice and ultimately care to patients. The clinic is run by a bladder clinical nurse specialist (CNS) alongside a microbiology consultant or registrar. The patient is reviewed by both teams and a plan is formulated which is then relayed to the patient's GP. This joint approach helps deal more effectively with patients struggling with multi-antibiotic resistance. Guidance on appropriate use of antibiotics with doses/duration can also be provided from the microbiology team's in-depth knowledge. Another outcome from this style of clinic is the expedition of imaging, other investigations, or onward referrals to other teams, such as gynaecology, through direct access to medical expertise rather than needing to await further input from a urologist. This collaborative working can build nursing confidence to guide patients and GPs on request with care options with a direct link to the microbiology team when patients run into trouble. Patients report the benefits from having regular CNS follow up as a relief at having a direct contact number with the specialist nursing team if they need help. This has helped colleagues in primary care and the emergency department, with the team able to prevent GP appointments and hospital admissions.

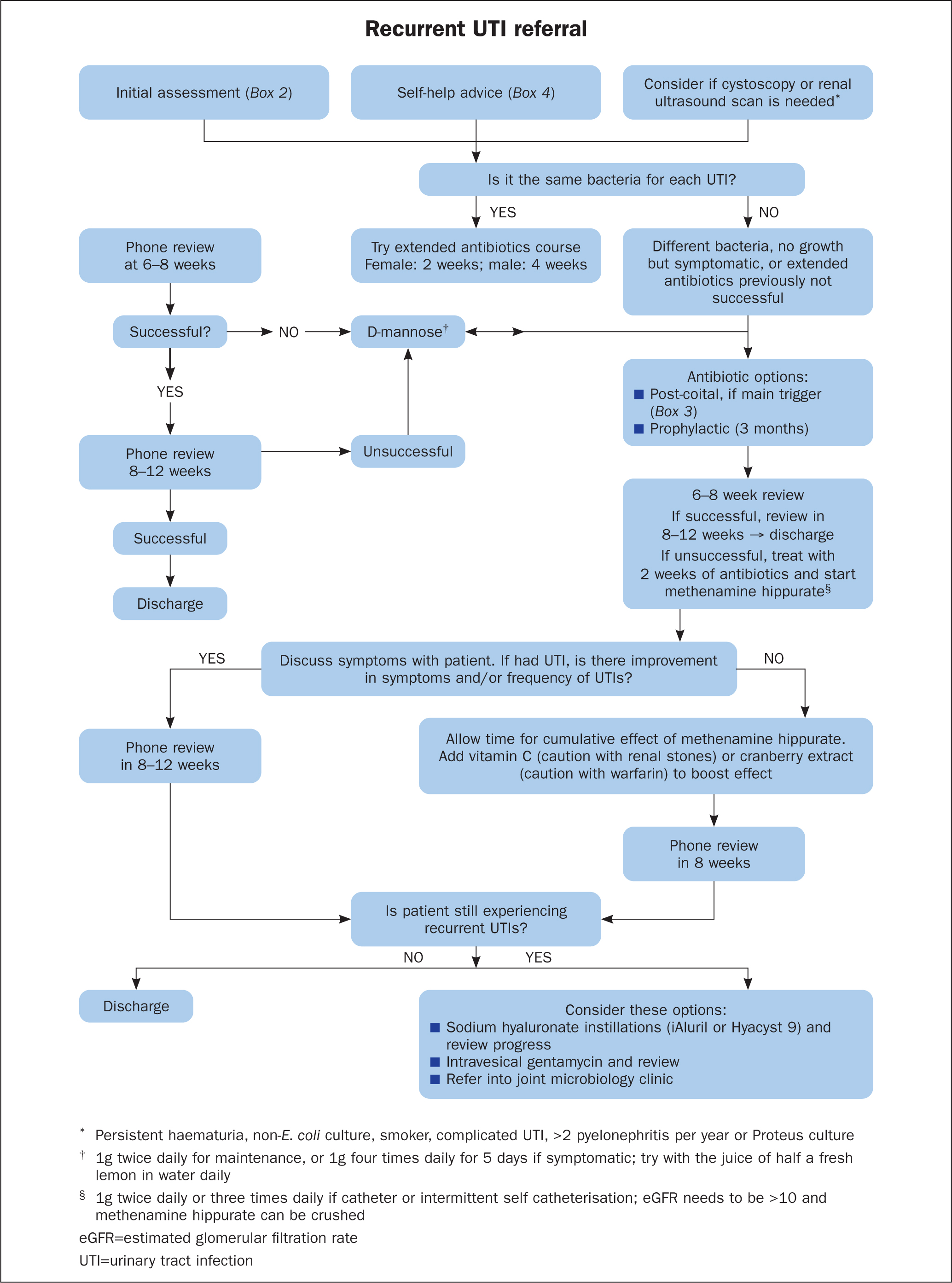

From review of the available literature and experience, Figure 1 outlines a proposed locally used guideline to support the management of recurrent UTIs in a nurse led team, to help provide high quality, evidence-based treatment. This helps ensure a consistent approach while still allowing flexibility to respond and adapt to individual needs, such as allergies or financial constraints. It is also important to ensure patients are listened to and involved in the decisions made around their treatments, which can help with engagement and compliance. Most patients are keen to stop antibiotics, and this supports exploration of other treatments where available.

The team now uses the guideline within practice to ensure consistent approaches to care, but with the flexibility and shared knowledge to respond and adapt to individual patient needs. Patients on long term, pre-existing treatment plans, for example bladder instillations or prophylactic antibiotic doses, have been reviewed to see if there is something else that can be offered, such as methenamine hippurate. Patients are often emotional at the first consultation, relieved to have someone actively listen to them and then have a contact, often saying they no longer feel alone. Telephone follow-up is then provided with an in-person consultation for the patient if they require any further help. There have been patients who have struggled to get urine samples sent for MC&S by their GP practice following a negative urinalysis via dipstick, despite being symptomatic. In some cases, the author's team have seen in clinic clear-looking urine, with no nitrates or leucocytes on urinalysis, but the patient is symptomatic, so urine is sent for MC&S and has then come back positive.

A solid working relationship with the local urology and microbiology teams has enhanced the general patient experience and helped with getting patients on the right medication/dose/duration in prescription format in a timely manner, with further follow up and consultation if the patient requires help in any way.

The use of methenamine hippurate has been a real benefit to the care provided to patients, being another option in the battle to improve symptoms and quality of life (QoL) for patients with recurrent UTIs. The ongoing intention is to review patients who have been on methenamine hippurate for 1 year and look at how effective this has been to inform further changes in practice. It also enables the move away from being so reliant on antibiotics, which is important due to growing global antibiotic resistances developing (McGuinness et al, 2018).

Further work is required on what investigations are needed for safe management of recurrent UTIs, such as cystoscopy. There are further new advances on the horizon in recurrent UTI management. Ahumada-Cota et al (2020) discussed the merits of an E. coli vaccine. In the author's local area patients are being offered the chance to get involved in the E.mbrace study, which is looking into such an E. coli vaccine for patients experiencing recurrent UTIs. Tache et al (2022) further discussed the properties of plant extracts to prevent and treat recurrent UTIs, such as pomegranate, black chokeberry, and cornelian cherry, which is interesting but further research is needed.

Conclusion

From this process of reviewing the practices of one nurse-led team and its management of recurrent UTIs, along with current research and literature, it is hoped that a more robust, consistent approach will be provided to patients from the specialist team. Although it is acknowledged that this will be an evolving process with guidance needing regular update as innovations become published.

KEY POINTS

- When addressing recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), it is important to start with the basics: good hydration and bowel habits, ensuring self-help steps are in place

- The health professional should listen to and act on patient's symptoms and not necessarily their ‘no significant growth’ urine samples

- Collaboration with urology and microbiology teams has proved beneficial in addressing patients' recurrent UTIs

- Give methenamine hippurate treatment 3 months to become established, before stopping or solely relying on this treatment

CPD reflective questions

- What is the difference between a complicated and uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI)?

- How do we define a recurrent UTI? Are recurrent UTIs more common in men or women? What are the reasons for this?

- Consider the impact of recurrent UTIs on the patient – how could these affect their quality of life?

- What is the concern with long-term use of nitrofurantoin?