In Italy, recent increases in the retirement age have led to a larger proportion of employees, particularly within the healthcare sector, remaining in the workforce well into older age. One of the consequences of Italy's ageing population is the increase in the number of nurses with an average age of 50 years, who possess a wealth of accumulated experience within the healthcare workforce (Ministero della Salute, 2021). This trend is particularly pronounced among nurses, where members of Generation X and Millennials – despite having a been employed in the health service for an average of 19 years – are significantly outnumbered by older colleagues from the Baby Boomer generation.

This demographic imbalance may create a unique set of challenges for healthcare institutions. First, it can complicate the process of effective knowledge transfer as older nurses approach retirement, potentially leading to valuable clinical expertise and insights not being transmitted to the younger generation. Second, collaboration within healthcare teams can be impacted by differing generational perspectives on work practices, communication styles, knowledge and the use of technology, which can vary widely across age groups. Ensuring that multigenerational teams work cohesively requires targeted strategies to bridge these differences, promoting a collaborative culture that values the contributions of each generation. Addressing these challenges is crucial to maintaining the quality and continuity of patient care in an increasingly strained healthcare system.

This issue is further exacerbated by Italy's ongoing hiring freeze in the healthcare sector. According to the European Commission's (2023)State of Health in the EU: Italy, Italy faces a severe nursing shortage, with staffing levels approximately 25% below the European average. This deficit is projected to deteriorate further as the output of newly qualified nurses has consistently declined since 2014 (European Commission, 2023). Current data indicate that 39.0% of Italian nurses are between the ages of 50 and 59 years, 31.0% are aged between 40 and 49 years, and only 15.0% fall within the 30 to 39 years age group (European Commission, 2023). Additionally, a mere 6.1% of nurses are under the age of 29 years, while 7.9% are over 60 years (European Commission, 2023). This distribution reflects a pronounced age imbalance within the nursing workforce, with a substantial representation of mid-career practitioners but few younger and older professionals.

When comparing these data with the age distribution of the general Italian population, significant differences emerge. According to the State of Health in the EU: Italy report, which uses the official demographic statistics provided by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), the 30–39 years age group accounts for approximately 13% of the general population in Italy, while the 40–49 years age group constitutes 17%, and the 50-59 years age group reaches 19% (European Commission, 2023). Additionally, the percentage of individuals aged under 29 years is around 30%, significantly higher than that observed in the nursing workforce (European Commission, 2023). Lastly, approximately 25% of the general population is aged over 60 years, a figure substantially higher than the corresponding proportion among nurses (European Commission, 2023).

Nursing teams today are composed of professionals spanning multiple generations, including Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980) and Millennials (1981–1996), who actively contribute to the workforce (Pew Research Center, 2019). Although most of the ‘Veteran’ generation (1925–1945) has retired, the interactions among the remaining generations are pivotal for fostering team cohesion and ensuring effective collaboration. These differences highlight a notable phenomenon: the nursing profession in Italy is characterised by low appeal for younger cohorts and a high prevalence of mid-aged practitioners, although the representation of those aged over 60 years is less pronounced compared to the general population. Several factors may contribute to this imbalance:

The underrepresentation of young nurses, coupled with the increasing care demands driven by the ageing general population, presents a concerning challenge. This scenario may result in a shortage of qualified nursing personnel in the coming decades.

The ageing composition of the workforce, coupled with the decreasing influx of early-career health professionals, is expected to create critical deficits in staffing levels, retention of clinical knowledge and continuity of patient care. Approximately 52 000 nurses were anticipated to retire between 2021 and 2025, further diminishing the workforce and potentially leading to the loss of specialised expertise and institutional knowledge (Mastrillo, 2023). This scenario underscores the pressing need to foster effective intergenerational collaboration within healthcare teams to ensure the seamless transfer of clinical competencies, including those cultivated through the extensive experience of long-serving staff, fundamental for maintaining high standards of patient care.

The concept of generational cohorts and their societal impact was first introduced by sociologist Karl Mannheim, who argued that generational identity emerges from shared historical events and experiences (Mannheim, 1952). This concept was later expanded by Strauss and Howe in their ‘generational theory’ (1991), which defines a generation as a group of individuals born within about a 20-year period who share formative experiences. According to this theory, such shared experiences contribute to a common identity among members of each generation, influencing their perspectives on work, career paths and leadership preferences (Stevanin et al, 2017). However, generational theory has faced criticism for being overly broad and imprecise in defining cohort boundaries, which complicates efforts to accurately identify generational differences (Strauss and Howe, 1991; Gordon, 2017; Pew Research Center, 2019).

Some researchers, such as Costanza et al (2012), have argued that significant differences do not exist between generations themselves, but rather among individuals within the same generation, influenced by age and life stage. This perspective raises critical theoretical and methodological considerations, suggesting that meaningful comparisons should focus on individuals at equivalent stages of their life cycle, avoiding the ‘cusp periods’ that often blur generational distinctions (Strauss and Howe, 1991; Pew Research Center, 2019).

In Italy, the nursing profession has undergone significant reforms in 1975, 1992 and 2001, reflecting changes in both educational standards and societal expectations (De Caro, 2019). Recent legislative changes have also emphasised the need for additional training in management, organisation, research and teaching to better prepare nurses for the complexities of modern healthcare.

Generational differences can pose significant challenges, particularly through negative interpersonal interactions that affect staff wellbeing. McGrath (2012) demonstrated that the inadequate understanding and management of generational tensions can give rise to unnecessary conflicts at both the individual and organisational levels. One notable phenomenon is horizontal hostility, defined as antagonistic behaviours among colleagues of similar hierarchical levels, which has been shown to diminish team morale and hinder workplace harmony (Alspach, 2007). The targets of horizontal hostility among nurses are often young, newly graduated nurses or those with less experience. They are frequently subjected to hostile behaviours from more experienced colleagues, who may consider them incompetent.

Additionally, Stevanin et al (2020) underscore the prevalence of conflicts in multigenerational nursing teams, highlighting the importance of further research to understand and mitigate these challenges, particularly within the Italian context. Developing strategies to bridge generational divides is crucial for enhancing integration and collaboration among nurses of different age groups. By capitalising on the unique strengths of each generation and addressing potential barriers to effective interaction, healthcare organisations can cultivate a more cohesive environment that promotes teamwork and improves care quality.

Aims

This study aimed to evaluate and compare the generational characteristics of Italian nurses, with a focus on how generational differences influence their perceptions and attitudes toward key aspects of nursing practice. Developing targeted strategies to enhance workplace wellbeing, job satisfaction and staff retention requires healthcare organisations to identify the specific needs and priorities of each generation. In this context, tools such as the Multidimensional Nursing Generations Questionnaire (MNGQ) are invaluable for providing important insights into the dynamics of multigenerational nursing teams (Stevanin et al, 2019). The MNGQ explores critical dimensions, including intergenerational conflict in nursing, which often arises from differences in values, work styles and communication preferences. Older nurses (aged 50 and over) may favour traditional methods, while younger nurses (aged younger than 35 years old) tend to prioritise flexibility and innovation. These differences can affect team cohesion and performance. Generational differences also shape attitudes toward patient safety. Older nurses may emphasise established practices and personal judgement, whereas younger nurses lean towards evidence-based approaches and technology. Bridging these perspectives is key to improving safety outcomes.

Relational challenges between generations, such as miscommunication or differing expectations, can also hinder collaboration. Older nurses often perceive younger colleagues as less experienced, while younger nurses frequently view older ones as resistant to change. Addressing these issues will be crucial for fostering mutual respect and trust in future healthcare teams.

Openness to change varies across generations. Younger nurses are generally more open to new practices and technologies, whereas older nurses may prefer stability and gradual transitions. Understanding these differences is important for managing change in healthcare settings. Work readiness, willingness and flexibility also differ by generation. It has been observed that younger nurses tend to be more adaptable to new roles or schedules, while older nurses provide consistency and reliability. Balancing these traits is essential for effective workforce management.

Methods

Study design

This research employed a cross-sectional study design. Sample and setting participants of the Italian nursing population were recruited through an online platforms via social media channels such as WhatsApp, Facebook and Instagram, and through an announcement on the website of the Nursing Professional Order. Data collection were carried out using an anonymous questionnaire hosted on the Microsoft Forms platform. A separate recruitment strategy beyond online methods was not employed, as ISTAT data indicate that in Italy, internet usage reaches 90% among individuals up to the age of 55 years and 57% among those aged 65 to 74 years (European Commission, 2023).

The recruitment period extended from 1 February 2023 to 15 February 2024 due to initial difficulties in enrolling participants from Generation Z. To ensure adequate representation of this age group, the recruitment timeframe was extended, which allowed for a more inclusive sample.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible participants for the study had to meet the following inclusion criteria. Participants were a:

Exclusion criteria included:

Measurements

Participants were recruited using the MNGQ, a validated Likert-type instrument (Stevanin et al, 2017; 2019). The MNGQ consist of 48 items designed to assess nurses' perceptions of their professional environment and the quality of intergenerational relationships within the workplace. Responses are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’.

The questionnaire is tailored to capture generational differences in perceptions and attitudes, considering variables such as generational cohort, gender and educational background. It evaluates six key factors:

This comprehensive approach enables the identification of generational trends and dynamics in the nursing profession, providing insights into strategies for enhancing collaboration and team effectiveness.

Ethical considerations

The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Bologna on 13 October 2022 (approval number 0245799). Participants were informed about the study's details, including its voluntary nature, and assured that their responses would be collected anonymously to ensure confidentiality. Individuals had the option to leave the survey at any point, either without providing any information or after partially completing the questionnaire. At the start of the survey, participants were required to give their consent before proceeding to the questions. Data were only transmitted to the survey site once the respondent clicked the ‘submit’ button at the end of the questionnaire.

Data analysis

Data were entered anonymously into a dedicated database and reanalysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Software version 28 for Windows. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the differences among groups, followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests. Pearson's chi-squared test was used for nominal variables, and Fisher's exact test was used for dichotomous variables.

The researchers categorised respondents through a cluster analysis into generational cohorts using established classifications commonly cited in the literature (Pew Research Center, 2019). The population was divided into the following groups: Veterans (1925–1945), Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1980), Millennials (1981–1996) and Generation Z (born after 1997).

This generational classification was chosen due to its widespread acceptance and relevance in studies examining workforce dynamics and intergenerational relationships. These cohorts represent distinct socio-historical contexts that shape values, attitudes and behaviours, making them particularly suitable for assessing differences in key dimensions of interest, including intergenerational conflicts, patient safety perspectives, relationship dynamics across generations, teamwork in multigenerational settings, adaptability to change, work propensity and availability, and negative interactions. By applying this framework, the researchers aimed to capture the nuances of intergenerational dynamics within the Italian nursing workforce, aligning their analysis with prior research and ensuring the comparability of findings across similar studies.

Findings

Characteristics of participants

The sample included a total of 908 Italian nurses who accessed the study, of whom only 891 provided consent to participate (98.1%). Among the 891 participants, two were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, resulting in a final total of 889 participants. The generational distribution of nurses showed that Generation Y (Millennials) comprised the largest group in the sample at 52.2% (n=464), followed by Generation X at 36.6% (n=325). Baby Boomers and Generation Z made up smaller proportions, being 5.5% (n=49) and 5.7% (n=51), respectively. The detailed characteristics of participants, divided by generation, are represented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Baby Boomers (1946–1964) n (%) | Generation X (1965–1980) n (%) | Millennials (1981–1996) n (%) | Generation Z (1997 and later) n (%) | Total n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| mean±SD | 61.31±2.094 | 50.73±4.393 | 33.63±4.258 | 24.59±1.117 | <0.001 | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 31 (63.%) | 276 (84.9) | 369 (79.5) | 44 (86.3) | 720 (81.0) | 0.003 |

| Male | 16 (32.%) | 49 (15.1) | 91 (19.6) | 7 (13.7) | 163 (18.3) | |

| Non-binary | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Prefer not to identify with any specific gender | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.6) | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 5 (10.2) | 49 (15.1) | 222 (47.8) | 45 (88.2) | 321 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Married, civil union, cohabiting | 36 (73.5) | 224 (68.9) | 236 (50.9) | 6 (11.8) | 502 (56.5) | |

| Divorced, separated | 5 (10.2) | 48 (14.8) | 6 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 59 (6.6) | |

| Widowed | 3 (6.1) | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.8) | |

| Education in nursing | ||||||

| Nursing diploma | 15 (30.6) | 117 (36.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0%) | 133 (15.0) | <0.001 |

| Bachelor's degree in nursing | 5 (10.2) | 51 (15.7) | 189 (40.7) | 40 (78.4%) | 285 (32.1) | |

| Master's degree | 17 (34.7) | 98 (30.2) | 179 (38.6) | 7 (13.7%) | 301 (33.9) | |

| First-level master's | 11 (22.4) | 42 (12.9) | 88 (19.%) | 4 (7.8%) | 145 (16.3) | |

| Second-level master's | 1 (2.0) | 15 (4.6) | 7 (1.5) | 0 (0.0%) | 23 (2.6) | |

| PhD | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Work experience (in months) | ||||||

| mean±SD | 436.41±70.853 | 318.10±96.147 | 114.56±48.746 | 25.88±13.227 | <0.001 | |

| Work experience in the current ward/assigned service (in months) | ||||||

| mean±SD | 212.57±142.731 | 129.94±119.749 | 46.90±47.696 | 12.82±10.772 | <0.001 | |

| Work setting | ||||||

| Outpatient care | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.2) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (3.9) | 13 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

| Community healthcare | 9 (18.4) | 41 (12.6) | 39 (8.4) | 4 (7.8) | 93 (10.5) | |

| Private hospital | 1 (2.0) | 12 (3.7) | 14 (3.0) | 11 (21.6) | 38 (4.3) | |

| Accredited private hospital | 4 (8.2) | 19 (5.8) | 28 (6.0) | 8 (15.7) | 59 (6.6) | |

| Public hospital | 35 (71.4) | 240 (73.8) | 378 (81.5) | 25 (49.0) | 678 (76.3) | |

| Education | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.0) | 7 (0.8) | |

| Healthcare services agency | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Work contract | ||||||

| Part-time | 3 (6.4) | 23 (7.2) | 13 (2.9) | 3 (6.0) | 42 (4.8) | < 0.001 |

| Full-time | 44 (93.6) | 296 (92.8) | 440 (97.1) | 45 (90.0) | 825 (94.9) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Work schedule | ||||||

| Day shift (morning only) | 20 (40.8) | 88 (27.1) | 48 (10.3) | 2 (3.9) | 158 (17.8) | < 0.001 |

| Two shifts (morning and afternoon) | 15 (30.6) | 121 (37.2) | 101 (21.8) | 6 (11.8) | 243 (27.3) | |

| Three shifts (morning, afternoon, night) | 14 (28.6) | 116 (35.7) | 315 (67.9) | 43 (84.3) | 488 (54.9) | |

| Employment type | ||||||

| Self-employed | 2 (4.1) | 6 (1.8) | 11 (2.4) | 3 (5.9) | 22 (2.5) | < 0.001 |

| Fixed-term contract | 0 (0.) | 5 (1.5) | 20 (4.3) | 10 (19.6) | 35 (3.9) | |

| Permanent contract | 47 (95.9) | 314 (96.6) | 433 (93.3) | 38 (74.5) | 832 (93.6) | |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Northern Italy | 15 (30.6) | 120 (36.9) | 155 (33.4) | 10 (19.6) | 300 (33.7) | < 0.001 |

| Central Italy | 10 (20.4) | 85 (26.2) | 125 (26.9) | 10 (19.6) | 230 (25.9) | |

| Southern Italy | 14 (28.6) | 90 (27.7) | 140 (30.2) | 8 (15.7) | 252 (28.3) | |

| Islands | 10 (20.4) | 30 (9.2) | 44 (9.5) | 23 (45.1) | 107 (12.0) | |

This study examined generational differences in perceptions and attitudes, considering variables such as generational cohort, gender and educational background of participants across six key factors: intergenerational conflict, perspectives on patient safety, relational challenges between generations, collaboration in multigenerational teams, openness to change, work readiness, willingness and flexibility.

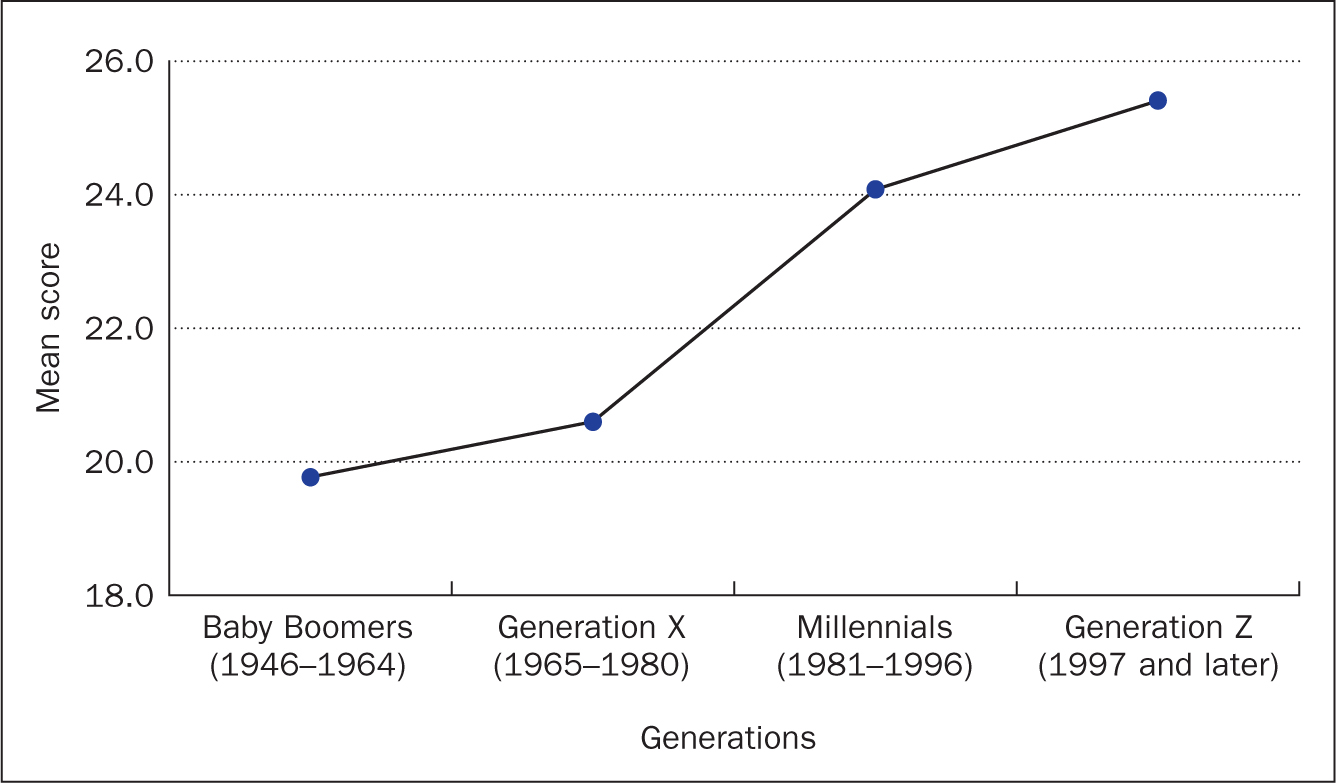

Intergenerational conflicts

Intergenerational conflict examines tensions or disagreements that may arise among nurses from different generations due to varying values, work styles and communication preferences. Conflicts between professional roles can impact team cohesion and performance, as well as impacting the overall quality of patient care.

The analysis revealed significant differences across generational groups. Baby Boomers reported a mean score of 19.77 (SD=8.41), while Generation X exhibited a slightly higher mean of 20.60 (SD=6.91). In contrast, Generation Y (Millennials) and Generation Z showed markedly higher scores, with means of 24.08 (SD=6.88) and 25.41 (SD=6.33), respectively. The post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni correction revealed significant differences in intergenerational conflicts (P<0.001), with younger generations (Generation Y and Generation Z) reporting higher levels of conflict compared to their older counterparts (Baby Boomers and Generation X) (Figure 1).

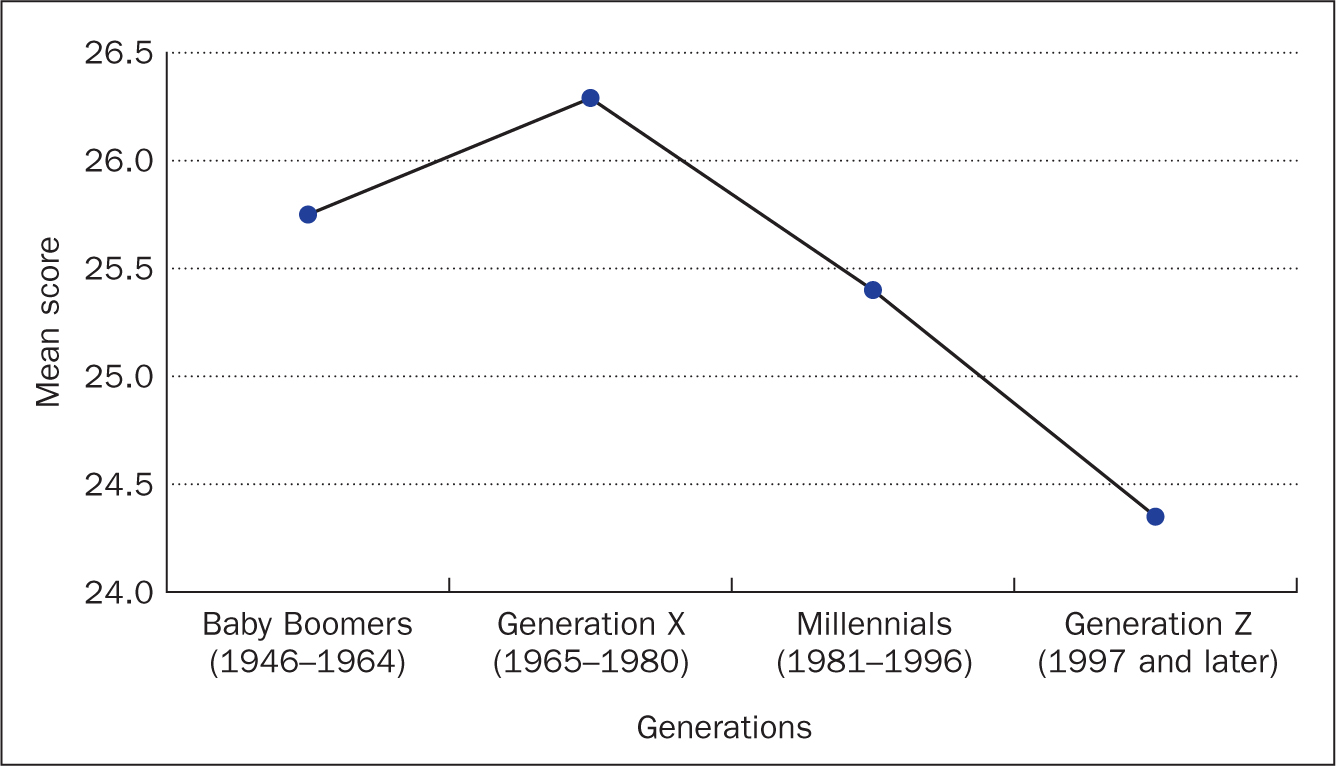

Perspectives on patient safety

This dimension evaluates how generational differences influence attitudes and behaviours toward patient safety protocols. Older generations may emphasise long-established practices and personal judgement, while younger generations might prioritise evidence-based approaches and technological tools. Understanding these perspectives can help bridge gaps and enhance safety outcomes. Analysis revealed statistically significant differences. Baby Boomers reported a mean score of 25.75 (SD=5.32), while Generation X had a slightly higher mean of 26.29 (SD=4.12). Generation Y (Millennials) exhibited a mean score of 25.40 (SD=4.60) and Generation Z reported the lowest mean score of 24.35 (SD=4.80). The post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni correction revealed significant differences in patient safety perspectives, with younger generations (Generation Y, P=0.038, and Generation Z, P=0.027) reporting lower levels of patient safety perspectives to their older counterparts (Generation X) (Figure 2).

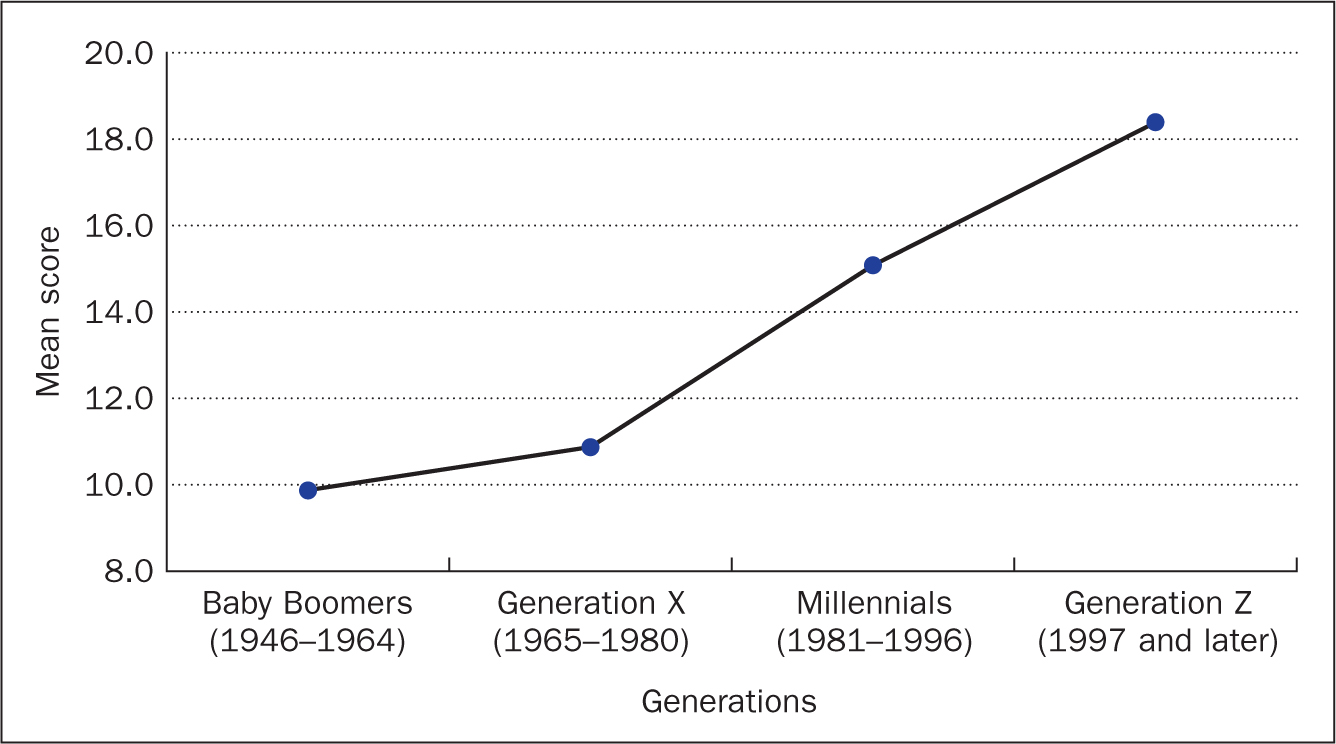

Relational challenges between generations

This dimension explores difficulties in interpersonal relationships across generational lines, such as miscommunication or differing expectations. Older generations might perceive younger colleagues as less experienced, while younger nurses could view their senior counterparts as resistant to change. Addressing these challenges is essential for fostering mutual respect and trust.

The analysis of the intergenerational relationship dynamics dimension revealed significant differences across generational cohorts. Baby Boomers reported the lowest mean score at 9.87 (SD=4.79), followed by Generation X with a mean score of 10.87 (SD=5.19). In contrast, Generation Y (Millennials) exhibited a notably higher mean score of 15.08 (SD=5.96) and Generation Z recorded the highest mean score at 18.39 (SD=5.38). The post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni correction revealed significant differences in intergenerational conflicts (P<0.001), with younger generations (Generation Y and Generation Z) reporting higher levels of intergenerational relationship dynamics compared to their older counterparts (Baby Boomers and Generation X) (Figure 3).

Collaboration in multigenerational teams

This dimension focuses on the ability of nurses from different generations to work together effectively. It highlights the strengths that each generation brings to the table, such as the experience and mentorship of older nurses, and the technological adeptness and adaptability of younger nurses. Promoting collaboration is key to leveraging these complementary skills.

Analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences. Baby Boomers had a mean score of 17.02 (SD=4.57), slightly higher than Generation X with a mean score of 16.21 (SD=4.11) and Generation Y (Millennials) with a mean score of 16.09 (SD=4.32). Generation Z reported a mean score of 16.58 (SD=4.53). The ANOVA results indicated no statistically significant differences in teamwork among the groups in multigenerational settings (P=0.479).

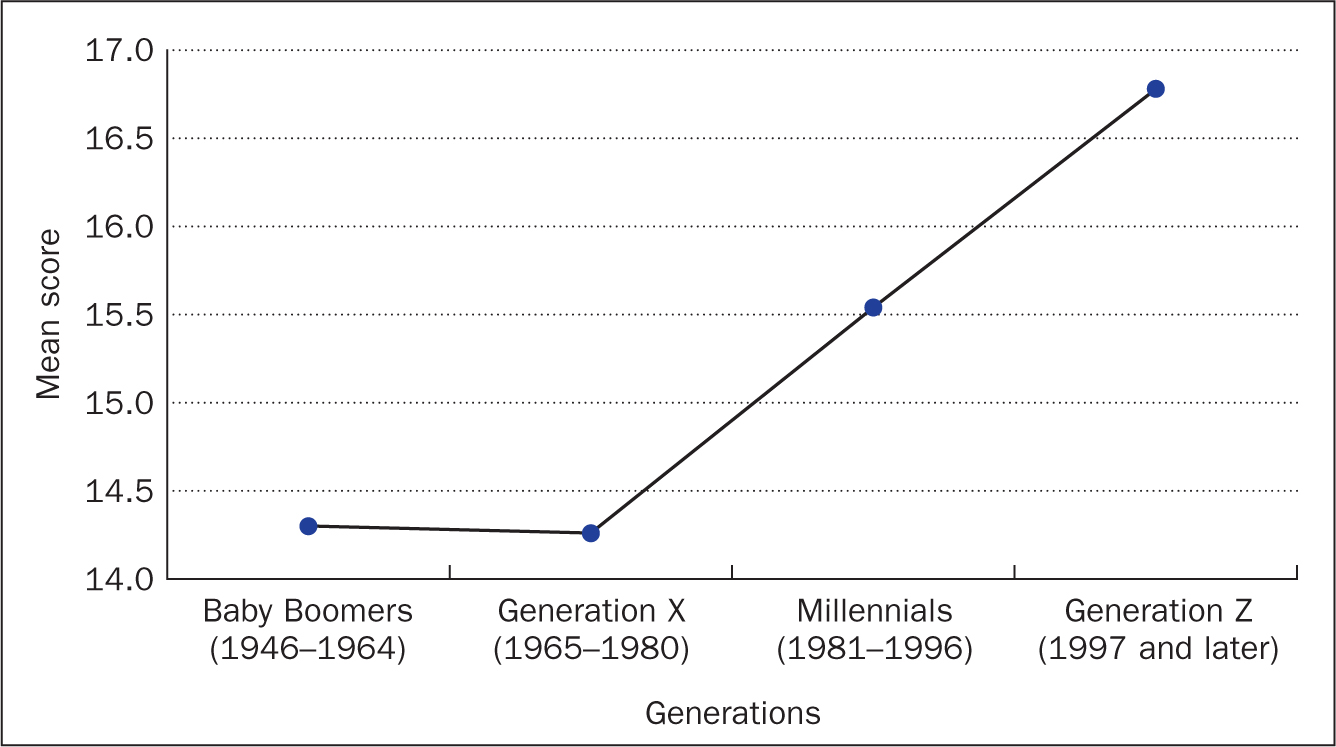

Openness to change and adaptability to change

This dimension assesses generational differences in accepting and adapting to changes in workplace practices, policies and technologies. Younger generations often exhibit higher levels of openness to innovation, while older nurses may prefer stability and gradual transitions. Understanding these tendencies can guide change management strategies.

Analysis revealed significant differences across the generational cohorts. Baby Boomers reported the lowest mean score of 14.30 (SD=3.38), while Generation X exhibited a similar mean score of 14.26 (SD=3.07). In contrast, Generation Y (Millennials) displayed a higher mean score of 15.54 (SD=2.94), and Generation Z reported the highest mean score of 16.78 (SD=2.61).

The post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni correction revealed significant differences in intergenerational conflicts (P<0.001), with younger generations (Generation Y and Generation Z) perceiving themselves as more adaptable to change compared to their older counterparts (Baby Boomers and Generation X) (Figure 4).

Work readiness, willingness and flexibility

This dimension examines the readiness and willingness of nurses to engage in their roles and adapt to varying work demands. Younger nurses might be more flexible in adopting new roles or schedules, while older nurses may exhibit greater consistency and reliability. Balancing these traits is crucial for effective workforce management.

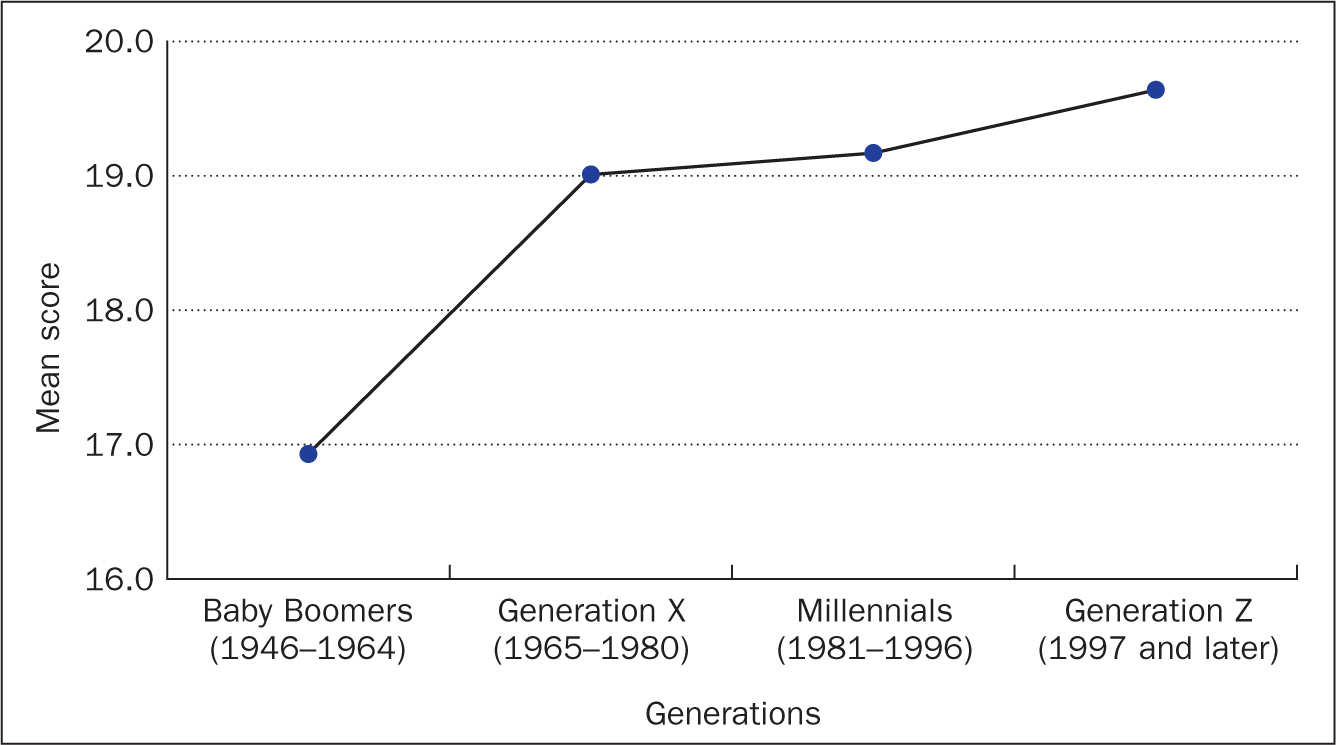

The analysis of the work propensity and availability dimension demonstrated significant differences across the generational groups. Baby Boomers exhibited the lowest mean score at 16.93 (SD=4.46), indicating a comparatively lower inclination towards work propensity and availability. Generation X showed a higher mean score of 19.01 (SD=3.69), closely followed by Generation Y (Millennials) with a mean score of 19.17 (SD=3.54). Generation Z, the youngest cohort, reported the highest mean score of 19.64 (SD=3.77). The post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni correction revealed significant differences in intergenerational conflicts (P<0.001), with younger generations demonstrate a higher propensity for work availability compared to Baby Boomers (Figure 5).

Discussion

The findings highlight significant generational differences within the Italian nursing workforce, reflecting diverse educational backgrounds, workplace adaptability and evolving professional norms. These distinctions are grounded in the profound shifts that the nursing profession in Italy has undergone in recent decades, particularly with the transition from vocational training to a bachelor's degree model (Dimonte, 1995). This generational divide in educational backgrounds shapes not only perceptions of professional roles but also the adaptability of nurses to workplace dynamics, technology and team flexibility.

Historically, nursing education in Italy followed a vocational path, culminating in a diploma focused on task-oriented care rather than theoretical understanding (Dimonte, 1995). Older generations, primarily Baby Boomers and Generation X, were trained under a model that prioritised hands-on patient care within clearly defined, routine tasks. This model, often supervised by religious institutions, instilled a practical mindset emphasising strict adherence to basic care standards rather than broader care planning or critical thinking (Antão, 2023).

However, with the implementation of the Bologna Process, the shift to a bachelor's degree framework brought an academic dimension to nursing, focusing on critical competencies and theoretical foundations (Davies, 2008). Millennials and Generation Z, as the first generations educated under this new framework, received training that emphasised critical thinking, evidence-based practice and the use of technology to improve patient outcomes (Aiken et al, 2014; Skela-Savič, 2023). This shift has provided younger nurses with expanded career opportunities and perspectives, opening new horizons for professional growth and marking a formal evolution in the role of nursing within Italy's healthcare system (Scarsini et al. 2022).

This generational gap in training is evident in workplace interactions. Whereas Baby Boomers and Generation X emphasise seniority and experiential knowledge, younger nurses may feel at a disadvantage when asserting their academic training in environments where experience is often equated with authority. This ‘seniority-based leadership’ perspective can create a sense of hierarchy, where Baby Boomers and Generation X assume authority based on tenure and practical experience, viewing academic credentials as secondary. Consequently, younger nurses may experience professional insecurity, perceiving their formal training as undervalued compared to the patient-centered expertise and extensive experience of their older colleagues (Meira and Kurcgant, 2016).

Moreover, formal academic training for younger nurses fosters a broader, research-oriented perspective on nursing that contrasts with the practical, task-based approach of previous generations. This difference shapes work style and adaptability to new practices. Younger nurses, trained in competency-based and technology-integrated environments, often exhibit flexibility in team dynamics and openness to evolving healthcare demands (Shin and Rim, 2023). Conversely, older generations, trained in a more structured and routine-oriented model, may rely on established practices, and prefer traditional, well-defined roles (Kourkouta and Papathanasiou, 2014). Considering these findings, the Italian nursing profession must recognise and integrate these generational differences to foster effective teamwork and collaboration.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is that, to the best of the researchers' knowledge, it represents the first quantitative analysis exploring the Italian nursing context from an intergenerational perspective. By examining generational dynamics within the same healthcare environments, this study provides valuable insights into the unique challenges and strengths of a multigenerational workforce in nursing.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. As a cross-sectional study based on a self-administered questionnaire, the data are subject to the inherent biases associated with self-reporting. Additionally, the representation of Baby Boomers in the sample was relatively low, potentially as a result of lower internet literacy or reduced use of digital platforms, which may have limited their ability to access the survey. Similarly, the low response rate among Generation Z nurses presents a further limitation to sample size. Although the cause of this underrepresentation is unclear, potential factors may include limited professional experience within healthcare settings, which could influence engagement in studies focused on workplace dynamics. Future research could address these limitations by exploring alternative recruitment methods to ensure broader representation across all age groups.

Conclusions

This study highlights the impact of generational differences on the Italian nursing profession, where evolving educational frameworks and workplace dynamics shape unique intergenerational experiences. The transition from vocational training to a university degree model has enhanced the scope of nursing practice, equipping younger generations with critical thinking and evidence-based competencies. However, this shift has also created challenges in integrating diverse professional identities and expectations within multigenerational teams. Whereas younger nurses bring a more academic, research-oriented approach, older generations rely on extensive patient-care experience and established practices.

To maximise the strengths of each generation and foster a cohesive workforce, healthcare institutions should prioritise mentorship, collaborative training, and continuous professional development that values both experiential and academic competencies. Supporting environments that bridge these generational distinctions not only fosters teamwork but also improves patient care. By addressing the unique attributes and perspectives each generation offers, the Italian nursing profession can establish a sustainable and adaptable model that meets the evolving needs of healthcare while supporting career satisfaction and growth across all age groups.