In the 21st century, dental caries are the most widespread infectious disease and remain the third commonest disease in the world (Petersen, 2009; Kassebaum et al, 2015). The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) defined early childhood caries (ECC) as the presence of one or more decayed (non-cavitated or cavitated lesions), lost (because of caries) or filled tooth surfaces in any primary tooth in a child aged under six years (AAPD, 2016).

ECC is a significant public health problem with harmful consequences (Kagihara et al, 2009). These include: pain, bacteraemia, sleeping problems, reduced social activities, reduced growth and development, speech and breathing disorders, premature tooth loss, the need for orthodontic treatment, compromised chewing, ear, nose and throat infection, loss of self-esteem and a poorer quality of life (Anil and Anand, 2017); poorer school performance and disrupted attendance at work for parents (Balaban et al, 2012); and high treatment costs for both those affected and society, and future harm to permanent dentition because of an unbalanced oral ecosystem (Samnaliev et al, 2015). ECC has the characteristics of a long-term condition (Krisdapong et al, 2014).

Treatment of ECC can be difficult because children may be nervous. However, ECC is not inevitable and can be prevented if the right information is given to families, including advice to make an appointment to see a dentist as the child reaches his or her first birthday. Few children aged 0–3 years are seen by a dentist and the average age at first consultation is four and a half years (Folliguet, 2006; Mika et al, 2018).

As health professionals working with children see them several times from birth, they are in a position to deliver the correct message regarding oral health (Murphy and Larsson, 2017). However, they do not have enough information about oral health because most of them see dentistry as the province of dentists and do not have enough time to learn about topics other than their own (Fuller et al, 2014).

There is a lack of information about transmission, which is a major factor in the pathogenesis of ECC. The constitution of the oral microbiome depends on its delivery by the mother and other family members (Alves et al, 2009; Pattanaporn et al, 2013; Lynch et al, 2015), and by lifestyle practices such as sharing items (Damle et al, 2016; Vozza et al, 2017) and kissing (Sharma et al, 2016).

Sugary food is cariogenic and encourages vertical transmission (Leong et al, 2013), which is facilitated by mutacins synthesis by maternal Streptococcus mutans (Kamiya et al, 2011). However, there is no consensus on the link between type of feeding (breast or bottle) and vertical transmission (Bullappa et al, 2017).

Prevention is more effective when different professionals give the same message (Congiu et al, 2014).

This study aimed to question five groups of health professionals—paediatricians, GPs, midwives, paediatric nurses and paediatric healthcare assistants (HCAs)—about their beliefs concerning oral health and ECC. In France, paediatric HCAs help paediatric nurses; they support bonding between the parents and the child and the mother when she starts breastfeeding. Pediatric nurses are specialist nurses for children. Generally, midwives, paediatric nurses and paediatric HCAs look after children while they are babies, which is before the first tooth erupts.

Materials and methods

Study population

A cross-sectional survey of paediatricians, GPs, midwives, paediatric nurses and paediatric HCAs in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, France, was conducted using a standardised questionnaire that could be returned by email.

The study population was identified by professional associations, social networks and public hospitals, which were asked to approach members about taking part in the study.

Survey

An e-questionnaire (created with Google Forms) was sent out between September 2015 and February 2016. It took approximately 5 minutes to complete. To limit bias, the first question had to be answered before moving on to the second one and so forth. The questionnaires were anonymous.

The survey instrument was a 4-item standardised questionnaire (questions 1–4) to be answered by all five types of professional; there were three questions for paediatricians and GPs (questions 5, 6 and 7) and one question for midwives, paediatric nurses and paediatric HCAs (question 8). Questions 1, 2, 3, 5 and 8 were closed questions with predetermined answers and questions 4, 6 and 7 were open ended.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using descriptive statistics with Excel software. For the closed questions, the percentages were calculated by Google Forms. For the open-ended questions, a systematic analysis of the contents was carried out.

Results

Sample characteristics

The participants included 494 health professionals: 79 paediatricians, 59 GPs, 217 midwives, 92 paediatric nurses and 47 paediatric HCAs, working full-time in both private and public centres.

The response rates were 58% of paediatricians, 11.7% of GPs and 31.7% of paediatric HCAs. The response rate for midwives and paediatric nurses could not be calculated because it was not possible to obtain the total number of midwives and paediatric nurses in Nouvelle-Aquitaine.

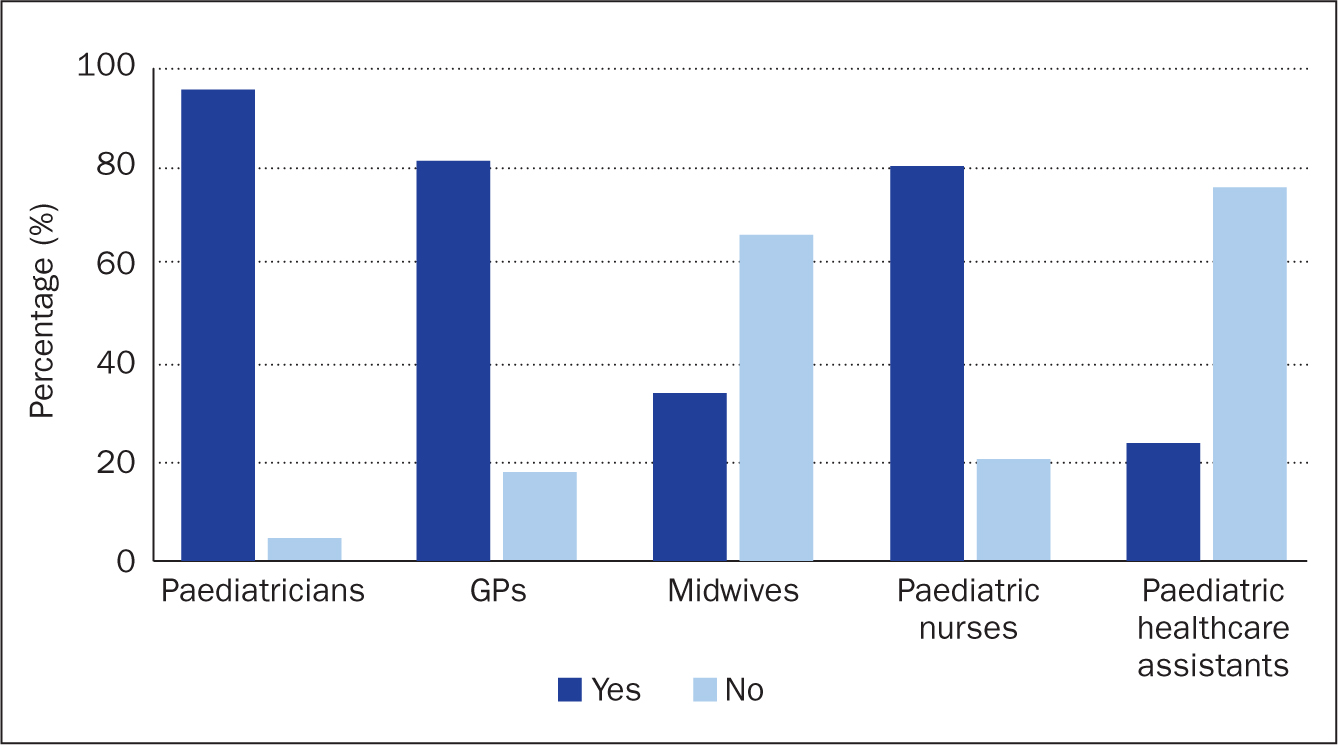

Question 1. Do you speak about oral health during consultations?

All types of practitioner spoke about oral health—some more than others (Figure 1). Most respondents (89.86%) discussed oral health during consultations. Among the professionals, 23% of paediatric HCAs, 34% of midwives, 80% of paediatric nurses 96.2% of paediatricians and 81.4% of GPs talk about oral health.

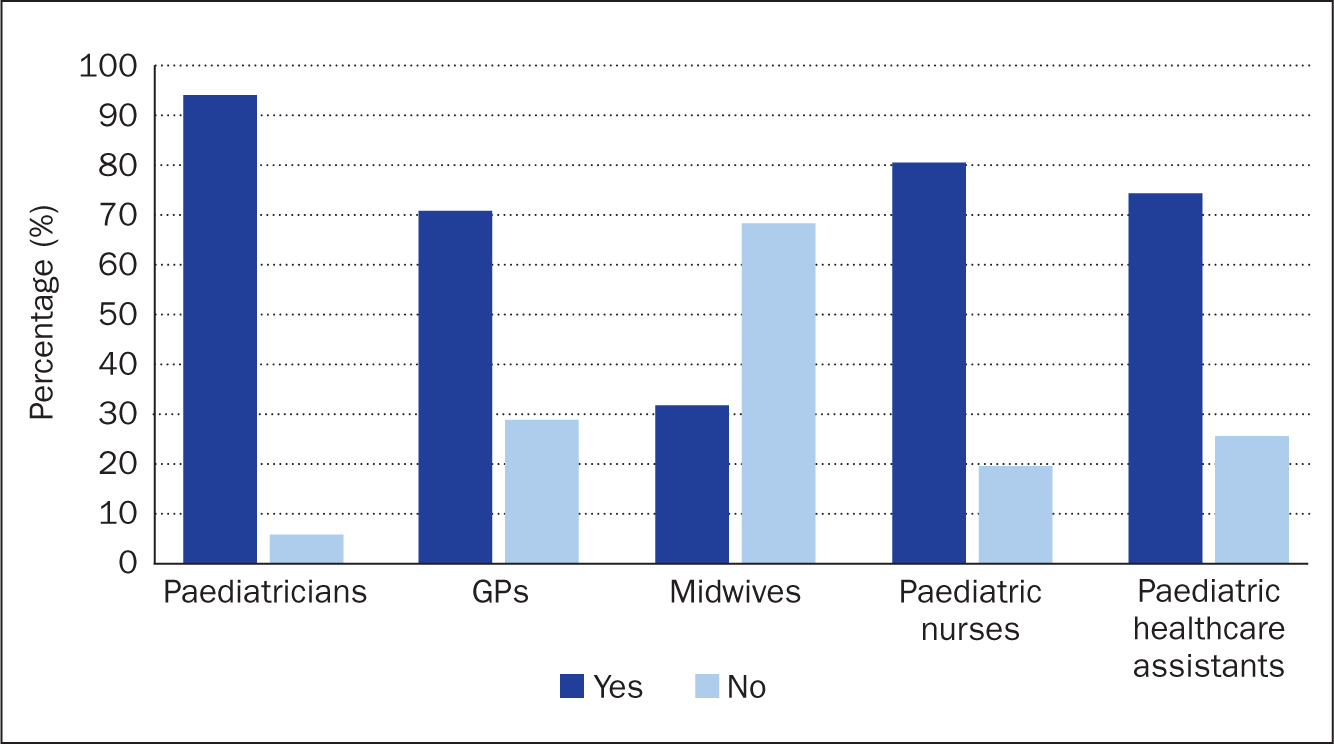

Question 2. Do you know the expression ‘baby-bottle syndrome’?

The expression has been defined as the presence of one or more decayed teeth resulting from dental caries or filled tooth surfaces between birth and 71 months of age (Tungare and Paranjpe, 2020). Most respondents said they knew this expression: 93.7% of paediatricians, 71.2% of GPs, 80.4% of paediatric nurses and 74.5% of paediatric HCAs. However, this was lower in midwives at 31.8% (Figure 2).

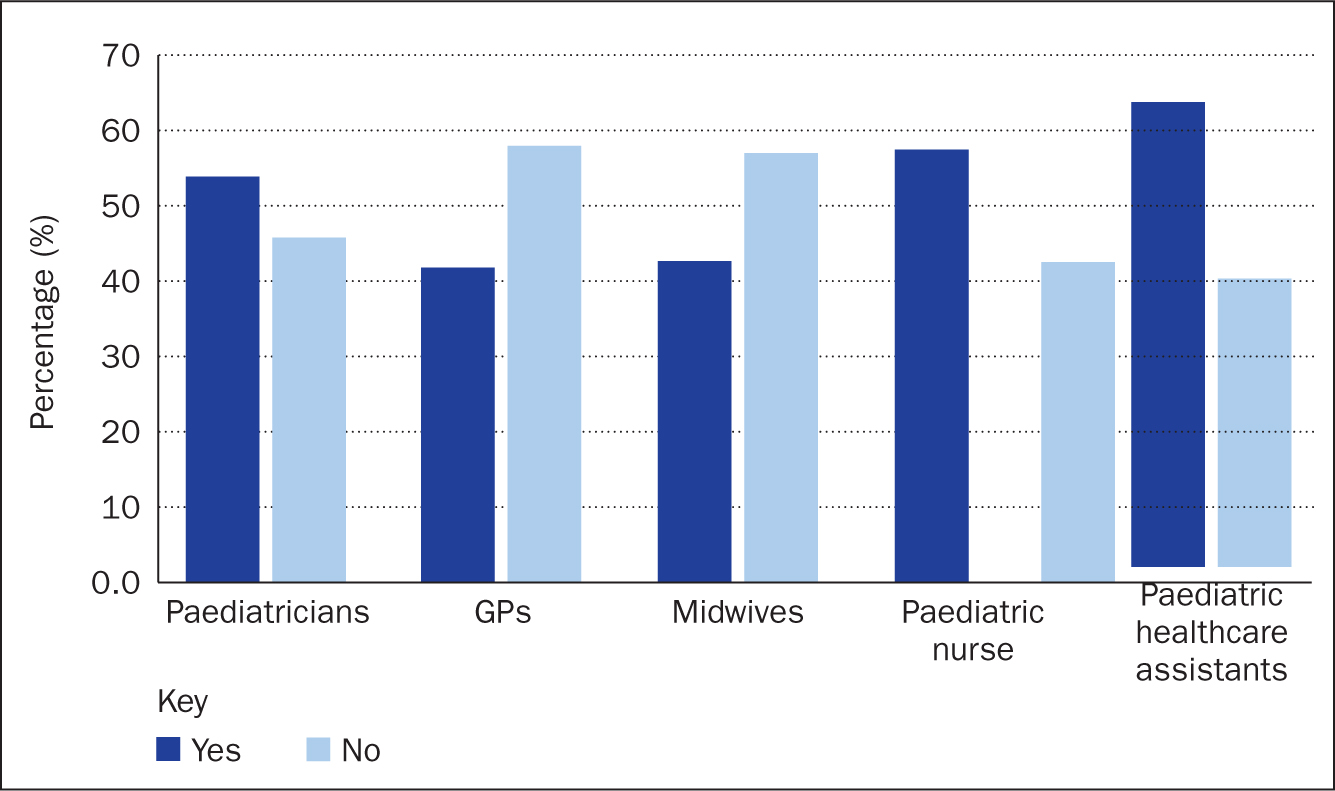

Question 3. Are you able to diagnose prodromal symptoms of caries?

Nearly half of respondents (49.28%) said they were able to diagnose caries. A proportion of paediatricians, paediatric nurses and paediatric HCAs thought they would be able to identify the early signs of caries. Most GPs and midwives thought they would not be able to do this. A few paediatricians and GPs said they were not sure they would be able to diagnose caries correctly (Figure 3).

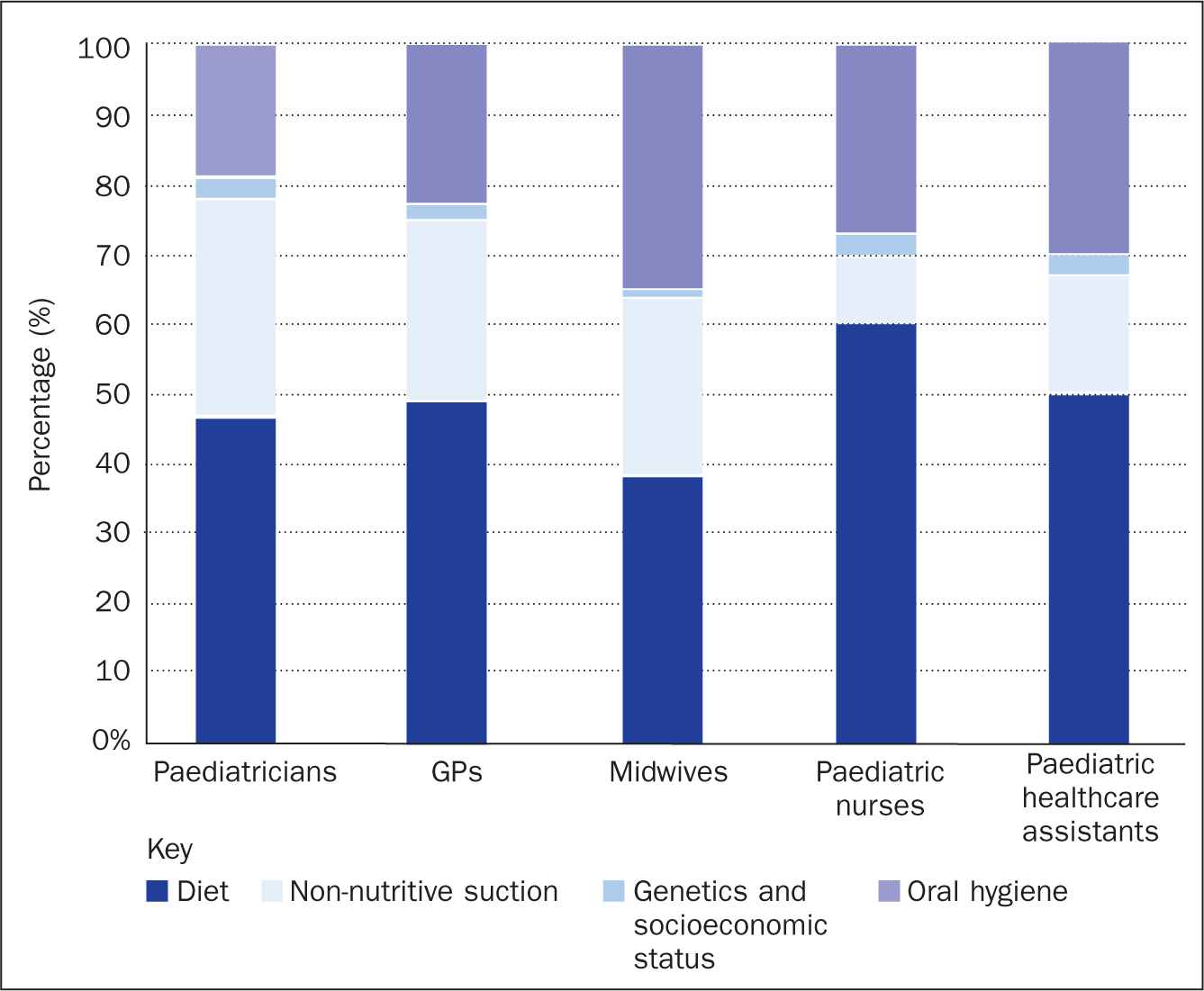

Question 4. Can you indicate the aetiopathogenic factors of caries?

All the respondents described four aetiopathogenic factors of caries: diet; genetics and socioeconomic status; non-nutritive sucking (eg on a dummy); and oral hygiene.

The main factor given by all the health professionals was diet. In this study, this concerned fizzy and acidic drinks, sugary food, frequent snacking and general diet. Paediatricians, GPs, midwives and paediatric HCAs thought that the most important aetiopathogenic factor was sugary food, while paediatric nurses were most likely to mention fizzy drinks.

For paediatricians and GPs, the second most important aetiopathogenic factor was genetics and socioeconomic status. Oral hygiene was put in second position by midwives, paediatric nurses and paediatric HCAs. Paediatricians and GPs said one aetiopathogenic factor was giving bottled milk at night.

For all health professionals, non-nutritive sucking was insignificant (less than 3%) (Figure 4).

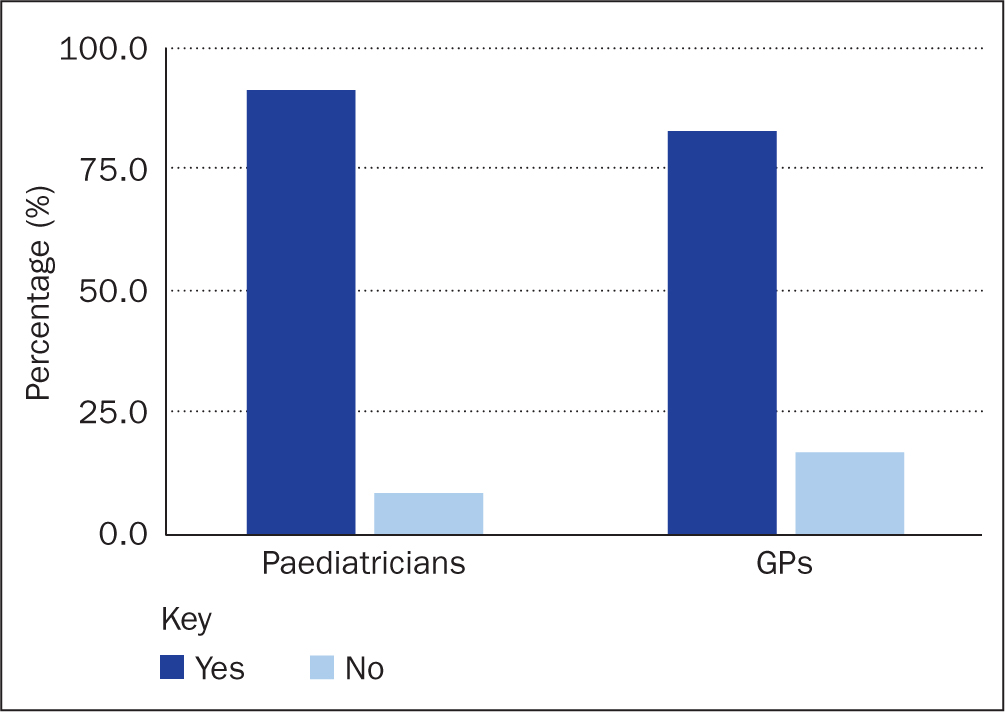

Question 5. Do you advise parents to consult a dentist?

Most respondents (83% of GP and 91% of paediatricians) advised parents to consult a dentist (Figure 5).

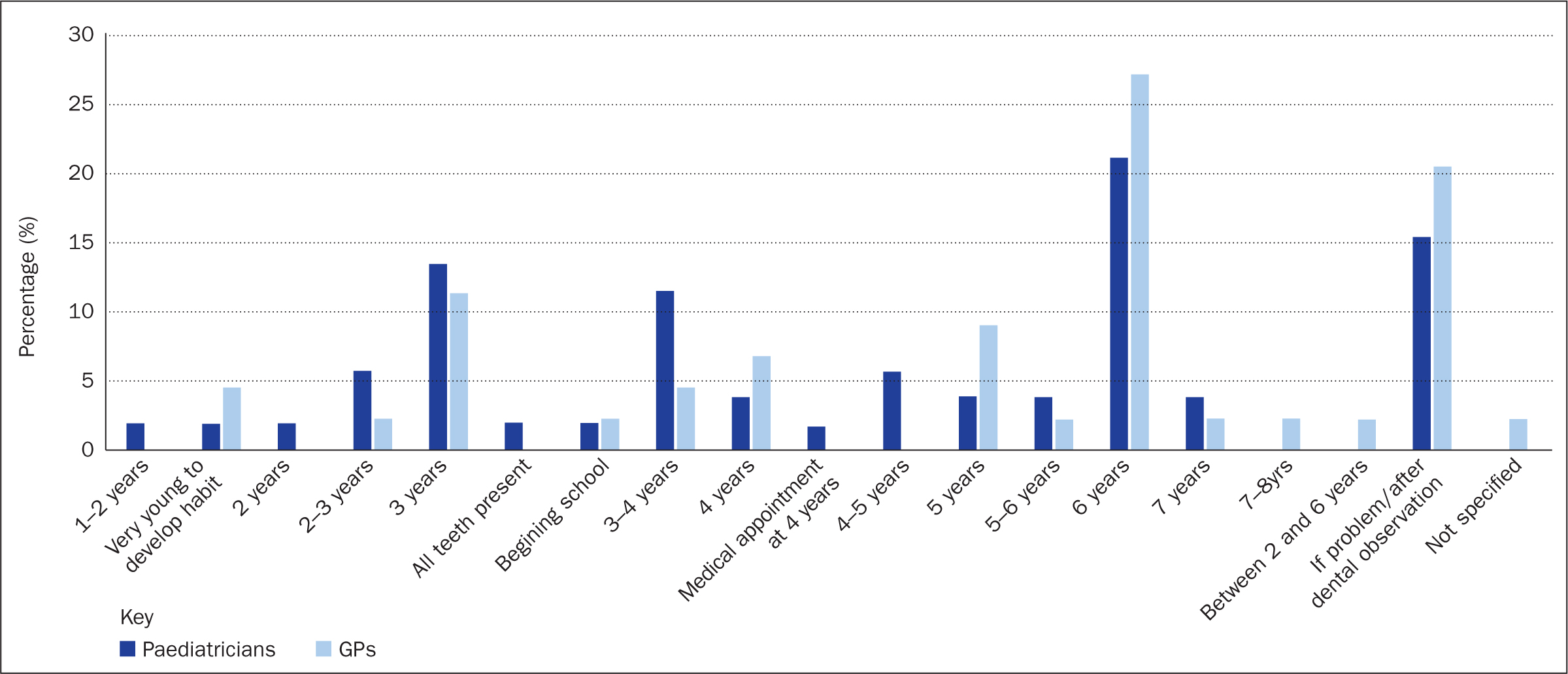

Question 6. At what age do you recommend seeing a dentist for the first time?

The answer given most often was 6 years, by 21.2% of paediatricians and 27.3% GPs. ‘In case of dental problem or after clinical observation’ was the second most common answer, given by 20.5% of GPs and 15.4% of paediatricians. The third commonest answer, given by 11.4% of GPs and 13.5% of paediatricians was 3 years old (Figure 6).

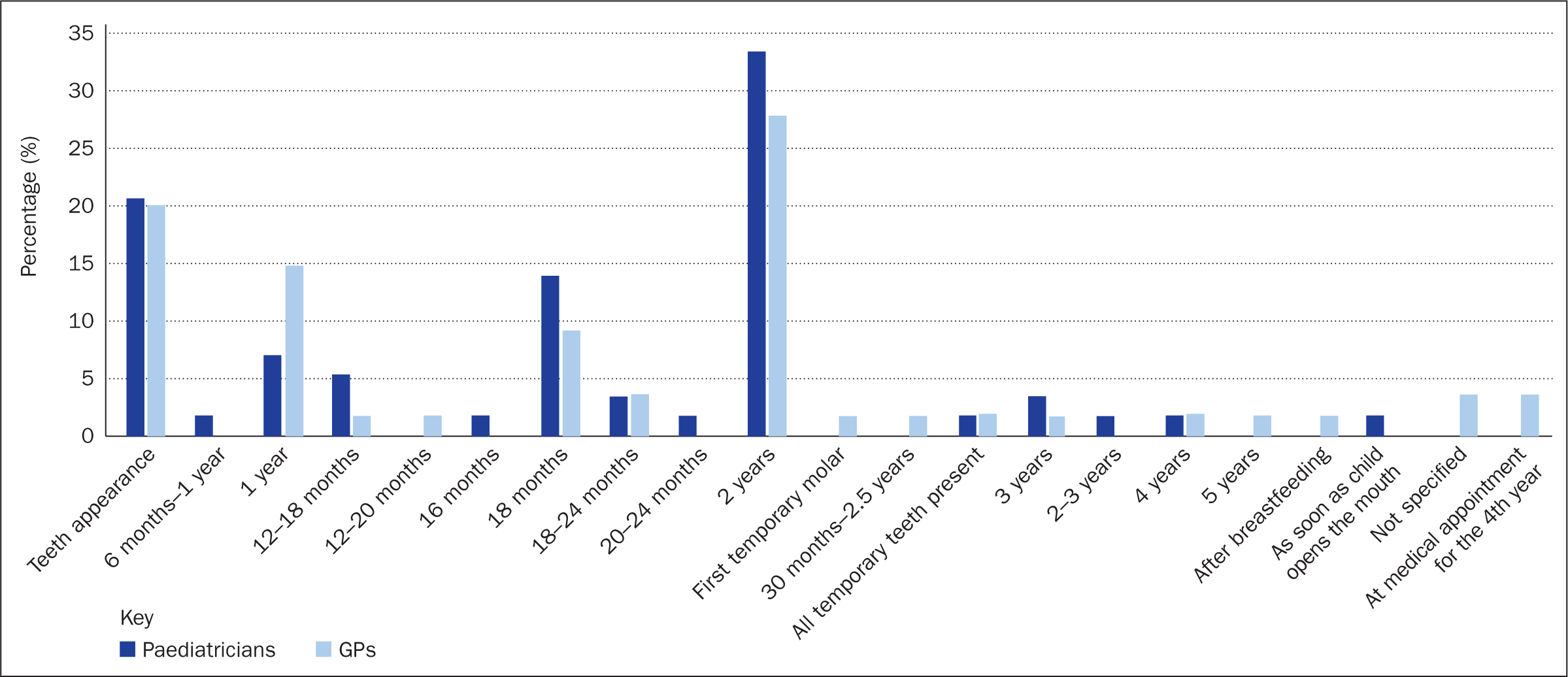

Question 7. At what age do you recommend toothbrushing should start?

The most frequently answer notified was 2 years of age for both paediatricians (33.3%) and GPs (27.8%), and ‘when teeth appear’ being the second most common answer (21% for paediatricians and 20% for GPs).

The third commonest answer was 18 months (given by 21.1% of paediatricians and 9.3% of GPs), and 12 months (given by 7% of paediatricians and 14.8% of GPs)—the correct answer (Figure 7).

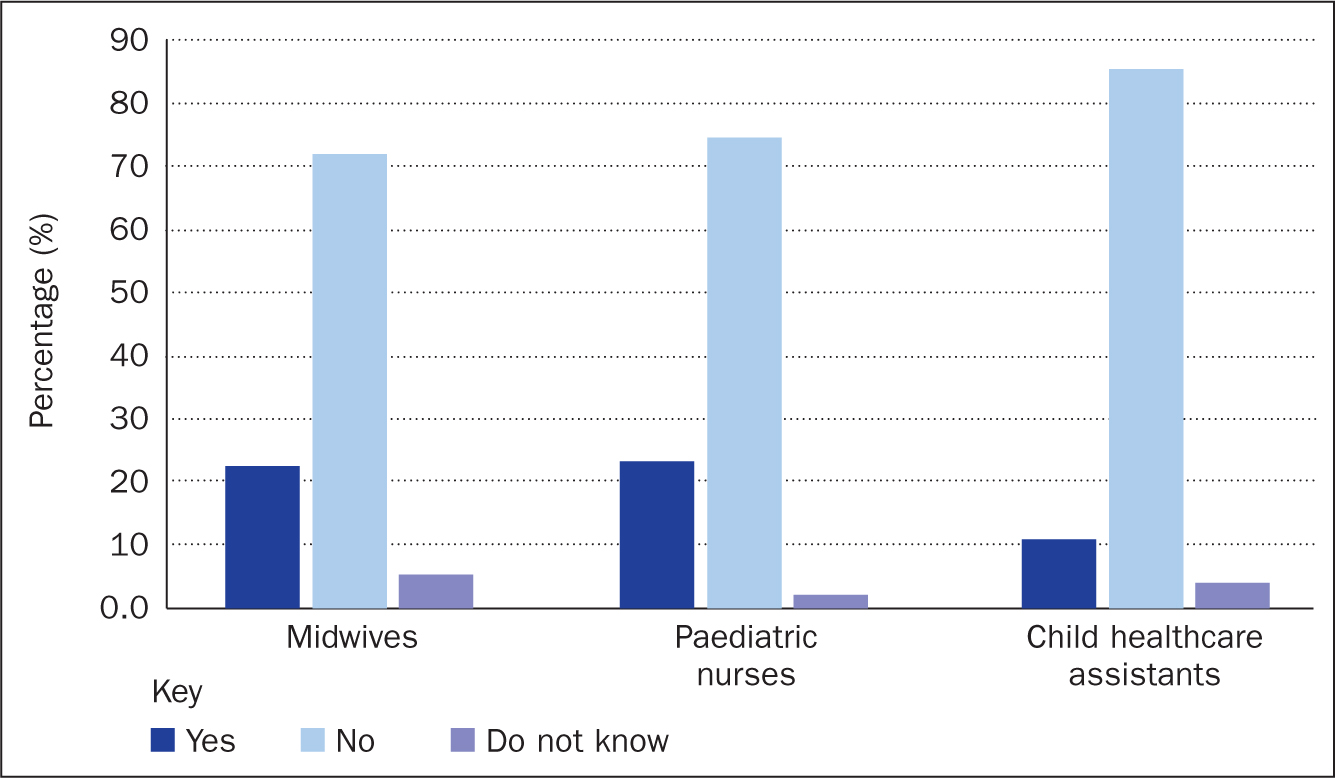

Question 8. Do you think that there is a link between breastfeeding and caries?

Most respondents (>70%) said there was no link between breastfeeding and caries. A few thought there was a link but some though breastfeeding protected children against caries.

Discussion

The discussion focuses first on the questions answered by all five types of practitioner then on questions for specific groups.

About question 1. Do you speak about oral health during consultations?

Paediatricians spoke more about oral health than GPs. The authors consider this may be because GPs thought that paediatricians had already discussed the topic with parents. GPs and midwives said that they lacked time. Paediatric nurses spoke more about oral health than midwives and paediatric HCAs, which may be because paediatric nurses follow children as they grow. Paediatric HCAs said their task was to help mothers when feeding their babies and they had to be aware of the wellness of both.

Wagner and Heinrich-Weltzien (2014) found that 90% of paediatricians gave information on diet, baby bottle use, oral hygiene and when to go to the dentist. Ehlers et al (2014) found that 92% of midwives explained the risk of developing ECC to parents.

About question 2. Do you know the expression ‘baby bottle syndrome’?

The majority of respondents (70%) knew the expression ‘baby-bottle syndrome’. Paediatricians were more familiar with this expression than GPs because they learn about diseases of young children during their training.

In this study, 80.4% of the paediatric nurses, 74.5% of the paediatric HCAs but only 31.8% of the midwives knew this expression. The low result obtained by midwives could be explained by the fact that midwives care for babies before their teeth appear (Dye et al, 2015).

About question 3. Are you able to diagnose prodromal symptoms of caries?

A higher proportion of paediatricians (54.43%) than GPs (42.37%) said they could identify symptoms. Several physicians thought they could recognise the signs but were not totally sure. The authors did not provide pictures on which to base their answer so it is not certain they are genuinely able to diagnose. Sezer et al (2013) found a significant proportion (49.8%) of paediatricians were not confident in their ability to detect the early signs of dental decay (Sezer et al, 2013).

It would be useful if non-dental health professionals were able to recognise the prodromal symptoms of caries because they see children more often than dentists. Alternatively, children could start seeing the dentist at an earlier age. In this study, paediatric HCAs seem to be better at diagnosing lesions from white spots than paediatric nurses and midwives.

In a Brazilian study, only 17.6% of health professionals thought white spots could be caries (Balaban et al, 2012) and were more likely to diagnose caries when there was a coloured spot (67%) or a cavity (78%). In the present study, some practitioners may have thought coloured but not white spots were a sign of caries. However, the authors think they may have been able to identify white spots as the beginning of caries from pictures.

About question 4. Can you indicate the aetiopathogenic factors of caries?

The main aetiopathogenic factors regarding health professionals' knowledge are, in descending order: extensive and frequent consumption of sugars; endogenous and environmental factors (lack of fluorides, genetics, caries in the family, disability or disease, low socioeconomic status); and poor dental hygiene. The frequency of sugar intake is more problematic than the amount of sugar itself (Evans et al, 2013; Sheiham and James, 2015).

Concerning sugar intake, in Lorca's (2013) study, 37.5% of GPs thought that it was better to breastfeed a baby aged over 6 months at night than to give it water in a bottle, 20% thought that soaking dummies in sugar or honey was a good way to pacify a child and 12.5 % thought it was acceptable to taste a child's food using his or her spoon (Lorca, 2013). Pacorel et al stated that 90.96% of GPs and paediatricians thought sharing a spoon or a pacifier was risky. Nearly all (98.54%) health professionals answered that giving a bottle of sugared milk before going to sleep could lead to caries; the figure was 95.63% if the bottled milk was sugar free (Pacorel, 2015).

Concerning fluorides, most of the non-dentist health professionals thought that not having fluoride treatment was responsible for decay. However, current recommendations support topical rather than systemic fluorides. The authors of the present study consider that too many physicians prescribe systemic fluorides. This was observed in Wagner and Heinrich-Weltzien's (2014) study, where only 23.5% of the paediatricians did not prescribe fluorides. In Brazil, 98.9% of paediatricians do not prescribe fluorides. Nevertheless, almost 90% of them recommend the use of fluoride toothpaste, in line with AAPD (2018) and the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (Toumba et al, 2019) guidance (Balaban et al, 2012).

Concerning endogenous and environmental factors, socioeconomic status is important but paediatricians and GPs are not aware of its significance in the pathogenesis of ECC. The authors may have asked that question in the wrong way and should have referred to ‘all the aetiopathogenic factors you know or suspect’.

The study by Anil and Anand (2017) confirmed that enamel hypoplasia was an independent risk factor for caries but the causal relationship with dental caries has not been established.

Low socioeconomic status, poor parental education, and lifestyle factors have significant influences on ECC.

About question 5. Do you advise parents to consult a dentist?

In this study, the majority of practitioners advise parents to consult a dentist but the authors do not know whether they raised this spontaneously or only if parents asked. In a survey by Sezer et al (2013), 80% of paediatricians had referred children to a dentist. Wagner and Heinrich-Weltzien (2014) found that nearly all paediatricians (90%) advised parents about dental visits.

About question 6. At what age do you recommend a child should see a dentist for the first time?

There was a wide range of answers to this question, which indicated a lack of knowledge of recommendations or a lack of well-established ones.

The answer given most often was the age of 6 years (21.2% paediatricians and 27.3% GPs), followed by 13.5% and 11.4% respectively at 3 years. In France, the government provides a free visit to the dentist for all children aged 6 years. This appointment is too late for a first oral consultation, especially regarding the prevention of ECC. The second most frequent answer was ‘in case of problems’ or ‘according to the clinical examination’, which means sending the child to a dentist in a curative rather than a preventive context. Nearly one quarter of paediatricians and GPs indicated an age but added that they would suggest making an appointment earlier in case of problems. This shows that practitioners know problems can occur before the age of 6 years. Paediatricians and GPs should ensure they are able to advise parents because, as Lorca's (2013) study showed, 80% of them do not know the best age for the first dental consultation.

A study conducted in Brazil with 182 paediatricians showed that 72.9% recommended consulting a dentist routinely and that 63.9% said the first visit should take place at the age of 1 year (Balaban et al, 2012). The rate of correct answers to this question was much higher than in our survey.

According to a study conducted in Germany in 2009, 63% of paediatricians would recommend consulting a dental surgeon for the first time after a child's second birthday, 15% after the third or fourth birthday, 13% after their first birthday and 9% at the eruption of the first tooth. These data, again, gave younger ages than in the present study, but these were multiple choice questions, which limits errors. Around two-thirds (66.3%) would decide depending on the child's dental status (Wagner and Heinrich-Weltzien, 2014), like the practitioners in the present study who said they would refer if there were problems.

The ages given by practitioners answering this question may seem too late for a paediatric dentist because it is common to see 3-year-old children with dental lesions.

About question 7. At what age do you recommend toothbrushing should start?

The answers to this question were varied, again showing a lack of a consensus among health professionals.

Only one in five (20.29%) advised to start tooth brushing as soon as the first tooth appeared, in line with the French government recommendation (Haute Autorité de Santé, 2010). Two years of age was the most frequent answer even though the first tooth appears at around the age of 6 months. In Lorca's (2013) study, 85% of GPs did not know at what age toothbrushing should start. Pacorel (2015) found that 59.94% of GPs did not know at what age toothbrushing should start; in that study, the answers were guided by closed questions. In Wagner Heinrich-Weltzien's (2014) study, 35% of paediatricians recommended tooth brushing as soon as the first tooth appeared, 52% at 1 year old and 12% at 2 years old.

The variety of responses concerning the age at which tooth brushing should start and the first dental visit should take place shows that recommendations for dentists are not sufficiently disseminated to other health professionals.

About question 8. Do you think that there is a link between breastfeeding and caries?

More than 70% of the practitioners surveyed believed there was no link between breastfeeding and caries (responses of individual professional groups are shown in Figure 8). Most of the paediatric nurses, paediatric HCAs and midwives thought there was no link between breastfeeding and caries. Furthermore, some of them believed breastfeeding protected teeth against decay.

Prakash et al (2012) showed that caries risk increased with unlimited milk feeding during the night, regardless of whether formula or breast milk was given (Prakash et al, 2012). Perera et al (2014) reached the same conclusions.

In a review, Anil and Anand (2017) confirmed that diet plays a significant role in the development of ECC, especially if it contains high levels of fermentable carbohydrates, and that bottle feeding at bedtime or at night has been associated with the start and development of caries in children.

A systematic review found that breastfeeding for more than a year and at night might be associated with an increased prevalence of dental caries (Valaitis et al, 2000).

Implications for practice

Around one in four health professionals interviewed for this study showed interest in our research; in particular, they wanted information and training. The lack of knowledge and training appear to limit the roles of the non-dental health professionals in children's oral health, as shown by previous studies (Bernstein et al, 2017; Murphy and Larsson 2017; Ramos-Gomez et al, 2017; T et al, 2017). Some studies have said primary ECC prevention needs to be integrated into the primary care setting to be effective (Douglass and Clark, 2015).

Conclusion

All paediatric health professionals should be able to identify the prodromic symptoms of caries to avoid ECC and its harmful consequences.

Collaboration between health professionals is essential for dental disease prevention and optimal oral health. Interprofessional collaboration may be a critical, cost-effective element in solving the multifaceted problem of ECC.

Non-dental health professionals could be ideal frontline practitioners. However, to begin the process of care and prevention effectively, they need to be aware of ECC. For that, interprofessional training could improve knowledge, confidence and clinical performance in the prevention of ECC and reduce oral health disparities. Such interprofessional collaborations could lead to introducing oral health as part of general health promotion.

The authors would encourage dental universities to carry out the same survey to inform all health professionals to find out what they know, and to ensure they all know about ECC prevention. Online information in general and even that from some heath and parenting organisations is often wrong about oral hygiene and dietary recommendations for children.

Each professional association has their own recommendations and consensus is lacking. For these reasons, the authors have drawn up a guide for health professionals in France with main recommendations concerning ECC prevention and detection. and should be disseminated. The authors can provide this on request: please note it is available only in French.