Nurses are role models for health (Blake and Patterson, 2015) and recognise that their own health behaviour influences the quality of patient care they are able to deliver (Blake and Harrison, 2013). However, nurses often do not follow their own advice in spite of being well informed about the impact. Bogossian et al (2012) found that 62% of nurses and midwives in Australia, New Zealand and the UK were overweight or obese. A cross-sectional study using the Health Survey for England found that 25% of nurses were obese compared with 14% of other care professionals, including doctors and dentists (Kyle et al, 2017). Unregistered care staff have the highest prevalence of obesity at 31%. Obesity prevalence within the general population showed similar patterns as in 2018, with 67% of men and 60% of women classed as overweight or obese (NHS Digital, 2020).

While the pressures of nursing may not be conducive to a healthy lifestyle, those joining the profession show similar problems from the outset. Malik et al (2011) and Hawker (2012) reported that approximately 40% of nursing students were within the overweight and obese categories. In Ireland, Burke and McCarthy (2011) found that nearly 20% of student nurse participants smoked and 19% were exceeding the recommended weekly safe level for alcohol consumption. Blake et al (2011) found that 77% did not consume five portions of fruit or vegetables per day, and Malik et al (2011) found that 43% of them also ate foods high in sugar and fat every day. Fewer than half of student nurses do the recommended amount of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity each week (Blake et al, 2011; Hawker, 2012).

Malik et al (2011) examined the health behaviour of registered nurses and preregistration student nurses, and found ‘room for improvement’ in both groups, advocating a need to target education and support service to improve the diet and exercise habits of nursing professionals. Kelly and Wills (2018) examined interventions addressing obesity and unhealthy lifestyles among nurses and concluded that there was insufficient evidence and also mixed messages about successful interventions to address these issues. The authors of the present study suggest the problem may not be a lack of knowledge about healthy behaviour but one of motivation.

Some studies have examined interventions offering additional support to nurses involving eHealth technology solutions such as mobile phone apps and text message reminders (Chyou et al, 2006; Tucker et al, 2016). Among other advantages, apps can be obtained at little cost, offer rapid and constant accessibility, and are anonymous and therefore perceived as non-judgemental. By 2017, more than 300 000 apps to support healthy lifestyles were available (Ferarra et al, 2019). To be effective, interventions need to be based on psychological theories, be focused on the need of individuals, tackle barriers to healthy lifestyles and offer motivational support, which is critical in achieving desired goals.

The aims of this research were to quantify the prevalence of obesity and unhealthy lifestyles within the student nurse population in the south west of England, identify barriers and potential solutions and explore the use of health-related apps that could lead to a healthier lifestyle.

Three authors of this paper research the cognitive basis of motivation and desire, particularly in situations with competing goals, to better understand human processes in order to develop ways to strengthen desires for healthy behaviour. The fourth author, a lecturer in nursing studies, is passionate about improving the health and wellbeing of the future NHS workforce.

Method

To support comparability with the findings of Malik et al (2011), the authors followed their methodology of using a cross-sectional online questionnaire to record nursing students' own perceptions of their behaviour, using a variety of Likert scales, checkboxes and free-text responses. While Malik et al (2011) had distributed their questionnaire by email, we sent potential respondents a link to the survey, which was hosted on an online survey platform.

Ethical approval was granted by the research ethics committee of the Faculty of Health and Human Sciences, University of Plymouth, before the online survey went live.

Materials

The online survey was followed up by an open-ended, in-class survey with a new sample. As stated, the online survey was based on that by Malik et al (2011), with questions on physical activity, general health, smoking and diet.

We added the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and Stunkard's figure rating scale (FRS) (Stunkard et al, 1983). AUDIT is a 10-question screening tool developed by the World Health Organization (Babor et al, 2001) to assess alcohol consumption, behaviour and problems associated with excessive alcohol use. The FRS presents nine line drawings of differently shaped male and female bodies, ranging from underweight to obese, and asks respondents to indicate which is closest to their body shape.

We included novel questions to assess current use of mobile phone health apps, barriers to using these apps and motivation to live a healthy lifestyle.

The in-class survey with the new sample consisted of four open-ended questions assessing current lifestyle, barriers to healthier living, support needed to achieve goals and the use of health apps.

Sample and recruitment

All 458 first-year nursing students studying at the University of Plymouth in UK were invited to participate in the online survey by email, and two follow-up reminders were sent to those who had not responded after 2 and 4 weeks.

In total, 154 (34%) provided responses. The majority were women (92.1%) and white (97.4%). Ages were in a range from 18-49 years (median=23.8; mean=26.1; SD 7.6); 95 respondents were aged 18–25 years, 27 were aged 26–29 years and 32 were aged 30 years or above.

The following academic year, all new first-year students were asked to take part in an in-class survey during lectures, using a Mentimeter survey that they could complete using their phones, tablets or computers. From a total cohort of 430, 207 (48%) participated in this survey. Demographic variables were not collected.

Results

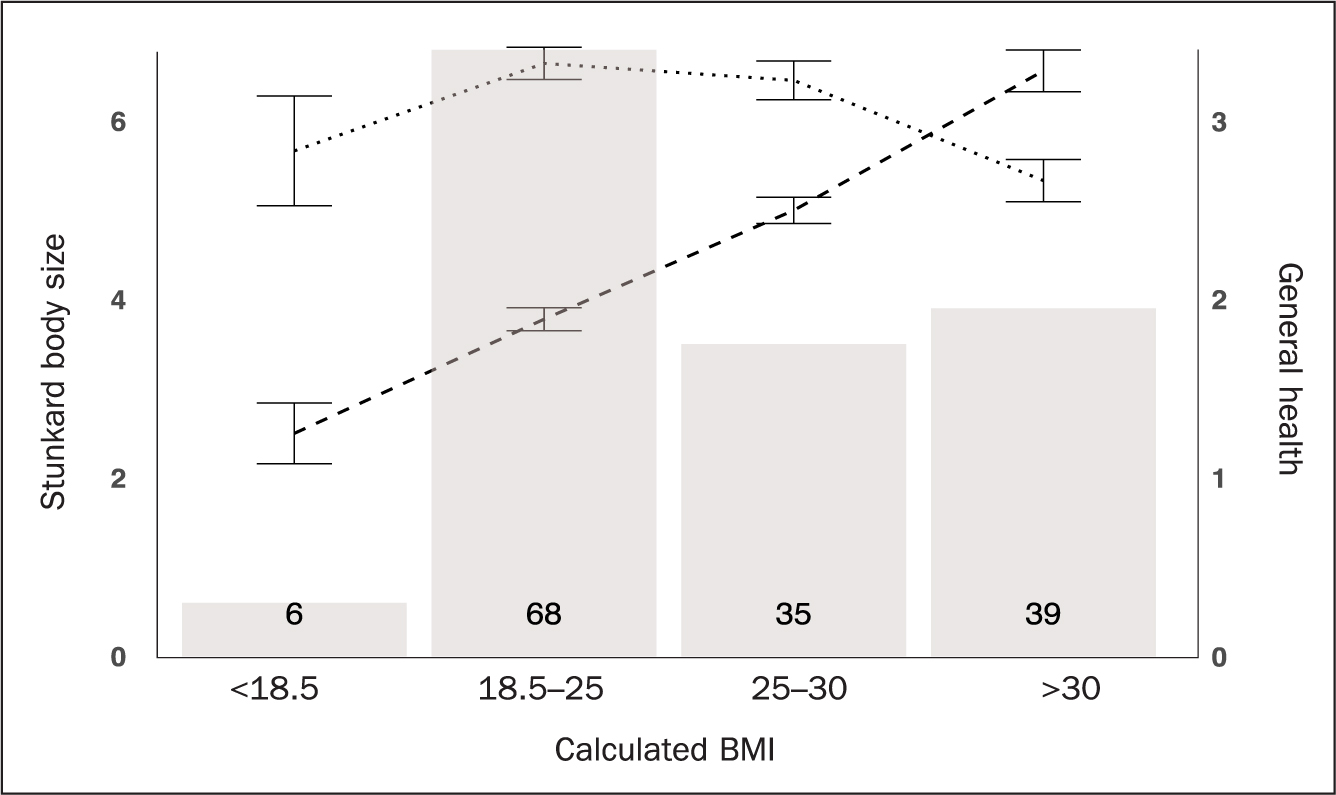

The mean self-reported body mass index (BMI) of participants was 25.4 (SD=6.5), which correlated (r=0.71) with the BMI calculated from height and weight reported by students (mean=26.7; SD 6.5). According to calculated BMI, 4% (n=6) were underweight (BMI<18.5), 46% (n=68) were in the normal range (BMI 18.5–25), 23% (n=35) were overweight (BMI 25-30) and 27% (n=39) were obese (BMI >30). BMI could not be calculated for six participants who did not provide valid height or weight data.

The mean value of Stunkard FRS was 4.8 (SD 1.7), correlating r=0.66 with calculated BMI (Figure 1), showing that the students had good self-awareness of their body shape and size in all four categories, which is essential if they are to start following weight-related behaviour.

There was a negative correlation (r=-0.31; P=0.001) between calculated BMI and ratings of general health, although both the mean health rating for overweight students of 3.23 and 2.67 for obese students were above the midpoint of the scale (1=very poor and 5=very good).

While the majority of participants (61%) stated they ate healthily, fewer than one-third (29%) ate the recommended five portions of fruit and vegetables per day, and two-fifths (40%) ate food high in fat and sugar every day, with 18% eating these types of food two to three times a day.

Student nurses had received little encouragement to make healthy food choices during the past month, (mean=1.4; range=0-4; SD 0.91) with the highest support coming from family members (mean=1.8; SD 1.4). They had little confidence that they would be able to avoid unhealthy foods such as chocolate or pizza (mean=3.5; SD 0.8)(Table 1).

Table 1. Confidence to avoid unhealthy food and snacks

| Type of food and snacks | Not at all confident | Slightly confident | Somewhat confident | Confident | Very confident | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Chocolate | 44 | 29.1 | 39 | 25.8 | 26 | 17.2 | 22 | 14.6 | 20 | 13.2 |

| Pizza | 19 | 12.6 | 30 | 19.9 | 30 | 19.9 | 31 | 20.5 | 41 | 27.2 |

| Fizzy drinks | 17 | 11.3 | 18 | 11.9 | 23 | 15.2 | 19 | 12.6 | 74 | 49 |

| Crisps | 12 | 7.9 | 24 | 15.9 | 26 | 17.2 | 41 | 27.2 | 48 | 31.8 |

| Cakes | 10 | 6.6 | 26 | 17.2 | 32 | 21.2 | 49 | 32.5 | 34 | 22.5 |

| Sweet biscuits | 9 | 6 | 16 | 10.6 | 33 | 21.9 | 51 | 33.8 | 42 | 27.8 |

| Sweets | 9 | 6 | 20 | 13.2 | 21 | 13.9 | 35 | 23.2 | 66 | 43.7 |

| Ice cream | 6 | 4 | 8 | 5.3 | 21 | 13.9 | 49 | 32.5 | 67 | 44.4 |

Price and availability of good quality fruit and vegetables were cited as the main reasons for not eating more of them (mean 1.7; SD 0.5)(Table 2).

Table 2. Reasons for not eating fruit and vegetables

| Very important | Important | Unimportant | Very unimportant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Price of fruit and vegetables | 39 | 25.8 | 73 | 48.3 | 28 | 18.6 | 11 | 7.3 |

| Ability to buy at university/placement | 36 | 23.8 | 71 | 47 | 34 | 22.5 | 10 | 6.6 |

| Money I have available to spend | 35 | 23.2 | 74 | 49 | 34 | 22.5 | 8 | 5.3 |

| Quality of fruit and vegetables | 33 | 21.9 | 85 | 56.3 | 27 | 17.9 | 6 | 4 |

| Time I have available to prepare | 26 | 17.3 | 72 | 48 | 40 | 26.7 | 12 | 8 |

| Likes and dislikes of my family | 25 | 16.9 | 46 | 31.1 | 51 | 34.5 | 26 | 17.6 |

| My knowledge about ways to prepare | 17 | 11.3 | 59 | 39.3 | 48 | 32 | 26 | 17.3 |

| How easy it is for me to get to the shops | 17 | 11.2 | 70 | 46.4 | 50 | 33.1 | 14 | 9.3 |

Participants were aware of the benefits and importance of regular exercise (mean=3.8; range=0–4; SD 0.4), and motivation levels to live a healthy lifestyle were generally good (mean=6.4; range=0–10; SD 1.9). However, only two-fifths (41%) met recommended levels of weekly physical activity, which is 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise (Donnelly et al, 2009). The most frequently reported barriers (Table 3) were tiredness, a lack of time and a lack of motivation.

Table 3. Self-efficacy, social support, knowledge and barriers to physical activity

| Variables | Range | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy for physical activity | 0–3 | 1.39 (0.94) |

| Social support for physical activity | 0–4 | 1.28 (0.85) |

| Knowledge about physical activity | 0–4 | 3.75 (0.39) |

| Barriers to physical activity | n | % |

| I am too tired | 94 | 61 |

| I don't have time to be physically active | 79 | 51.3 |

| I have no motivation | 51 | 33.1 |

| I need rest and relax in my spare time | 47 | 30.5 |

| I cannot afford it | 46 | 29.9 |

| I cannot be bothered | 41 | 26.6 |

| I have young children to look after | 38 | 24.7 |

| There is no one to be physically active with | 33 | 21.4 |

| I am not a sporty type | 33 | 21.4 |

| I don't enjoy it | 21 | 13.6 |

| I am active enough | 21 | 13.6 |

| I am too fat/overweight | 15 | 9.7 |

| I am injured | 15 | 9.1 |

| I might get injured or damage my health | 13 | 8.4 |

| My health is not good enough | 11 | 7.1 |

| There are no suitable facilities | 8 | 5.2 |

| Traffic is too heavy/I don't feel safe | 7 | 4.5 |

| I have lost contact with my family/friends | 6 | 3.9 |

| I am too old | 2 | 1.3 |

| I don't think it's important | 2 | 1.3 |

There was a lack of social support for physical activity, with student nurses feeling they had received only slight encouragement from friends, family, partners or colleagues during the past month (mean=1.3; range=0-4; SD 0.9).

It is recommended that adults aged 18–64 years should get 7–9 hours of sleep per night (National Sleep Foundation, 2021). Only 61% (n=93) of our participants reported getting this more than half the time. Insufficient sleep can compromise health and wellbeing (Hirshkowitz et al, 2015), and lead to increased dietary intake (Capers et al, 2015), which consequently raises BMI and the risk of type 2 diabetes (Cappuccio et al, 2008).

The data on drinking and smoking were more encouraging. One in six (17%) were current smokers, and more than half of these (58%) intended to quit smoking in the next year. Almost all participants (98%) reported having an alcoholic drink no more than 2-3 times per week, which is within recommended guidelines of no more than 14 units a week (NHS Digital, 2018). A unit of alcohol is about a single small shot measure of spirits or half a pint of lower-to-normal strength lager, beer or cider. A small glass of wine contains about 1.5 units of alcohol. However, there were tendencies to binge drink, with two-fifths (40%) reporting having more than five drinks on a typical drinking day, with 19% having five or six drinks, 13% seven to nine drinks and 7% having 10 or more. One in seven (15%) reported consuming six or more drinks a day on a monthly basis, and 7% did so weekly.

More than half of participants (56%) reported currently using a health-related application on their smartphones. The most popular supported exercise (33%) and diet and healthy eating (24%), with very few used for smoking (0.9%) or alcohol cessation (0.5%). In an open-ended free-response question, commonly reported barriers to using eHealth apps were: ‘Not sure which one to get’; ‘Can't commit to it’; ‘They are too expensive’; ‘I find them boring and do not keep up to date with them’ and ‘I don't have the time to use them or even understand how to use them’.

Overall, student nurses were aware of their body shape but did not understand how to eat healthily; most did not drink excessively although there was a tendency to binge drink; most of the few who did smoke wanted to quit soon; and they did not exercise enough although they understood the benefits and, while they wanted to take more exercise, they lacked the confidence to do so. Importantly, they did not receive social support to engage in a healthier lifestyle, and felt constrained by time, money and circumstances.

We repeated these analyses to compare the three age groups (18-25; 26-29; and 30+) and found some lifestyle differences in health behaviour (Table 4). Although the age groups did not differ significantly in calculated BMI, the younger age group's self-reported BMI was lower, they selected smaller body shapes on the Strunkard test and reported greater motivation to be healthy than the older groups. The older two age groups were more likely to say that having children to look after was a barrier to being physically active, they received less encouragement to make healthy food choices from family members and their consumption of fruit and vegetables was more likely to be influenced by the likes and dislikes of their family. The 18-25 group expressed lower confidence in being able to resist eating pizza, were more likely to drink six or more drinks on one occasion and drank more per day.

Table 4. Variables where age groups differed

| Variable | 18–25 years (n=95) | 26–29 years (n=27) | 30 years and above (n=32) | Statistic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | ||

| Calculated BMI | 93 | 25.7 | 6.3 | 27 | 28.6 | 6.4 | 31 | 28.0 | 6.6 | F(2, 148)=3.03; P=0.051 |

| Self-reported BMI | 76 | 23.8 | 5.6 | 25 | 29.0 | 6.2 | 27 | 26.3 | 7.9 | F(2, 125)=6.66; P=0.002 |

| Stunkard body shape | 93 | 4.4 | 1.5 | 27 | 5.5 | 1.9 | 32 | 5.3 | 1.7 | F(2, 149)=7.18; P=0.001 |

| Motivation to be healthy | 93 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 27 | 5.6 | 2.0 | 32 | 5.8 | 2.3 | F(2, 149)=7.31; P<0.001 |

| Children as barrier | 95 | Yes=8 | 27 | Yes=15 | 32 | Yes=15 | χ2 (2)=35.8; P<0.001 | |||

| Healthy food choices | 93 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 26 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 32 | 1.3 | 1.2 | F(2, 148)=4.03; P=0.020 |

| Family influence | 93 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 26 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 29 | 1.9 | 1.0 | F(2, 148)=9.96; P<0.001 |

| Able to resist pizza | 92 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 27 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 32 | 3.8 | 1.2 | F(2, 148)=3.31; P=0.039 |

| Binge drinking | 93 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 27 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 32 | 1.6 | 0.8 | F(2, 149)=4.35; P=0.015 |

| Drinks per day | 86 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 23 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 26 | 1.8 | 0.9 | F(2, 132)=5.94; P=0.025 |

We specifically addressed these barriers to healthy lifestyle in the following year's in-class survey with a new sample. Of these students, 53% answered ‘What do you need to do to be healthier’ by stating that they need to have a better diet (less sugar, more fruit and vegetable consumption and less junk food), with 52% mentioning taking more exercise. When asked ‘What is stopping you?’, the most frequent answer was a lack of motivation (enthusiasm, willpower, self-control, laziness and procrastination: 31%), followed by a lack of time and busy lifestyle (university, children, work and other commitments: 30%). In answer to ‘What kind of support do you need?’, 24% said they needed financial support (child care, gym and food), and 21% professional support (dietitian, personal trainer or mental health professional).

Other frequent answers concerned time management (19%), personal support (partner, family and gym buddy: 19%) and motivational support (18%). Finally, ‘How could a smartphone help?’ was most frequently answered by using diet tracking apps (food, planning, reminders, steps and calories: 43%). Although 22% would use their mobile phone to gain some inspiration (meal plans, simple recipe ideas, exercise plans and shopping lists), 24% felt that technology alone could not help to achieve their goals.

Discussion

Student nurses in the South West of England engage in numerous unhealthy lifestyle behaviours and half are overweight or obese. This substantiates previous findings in the literature about unhealthy lifestyles among student nurses (Blake et al, 2011; Malik et al, 2011; Hawker, 2012). There is a clear discrepancy between the nurses' individual perception of their own health and their self-reported engagement in healthy lifestyle behaviours.

A positive correlation between Stunkard FRS and calculated BMI suggests that student nurses are aware of their body size. This finding challenges previous research that showed overweight individuals were more likely to underestimate their body weight (Robinson, 2017).

As the prevalence of obesity in the UK shows annual increases (NHS Digital, 2020), physical exercise may be an important factor in tackling this growing problem. This also plays a key role in the prevention of long-term health conditions and the lowering of mortality risk (Warburton and Bredin, 2017).

Despite the importance of regular exercise in the maintenance of good health, only two-fifths of students surveyed stated that they engaged in the recommended weekly exercise regimen. Considering that 33% of student nurses reported lacking motivation to engage in exercise and 27% stated they could not be bothered, these findings were not surprising and were also similar to what Malik et al (2011) reported. This was despite students being knowledgeable about the importance of regular exercise for good health, and expressed a good motivation to live a healthy lifestyle. Clearly, there is a large disconnect between knowledge and its application regarding regular engagement in exercise. Other frequently reported barriers were tiredness, lack of time and a need to rest.

Therefore, a health intervention aimed towards student nurses should seek to address these barriers by being low cost, require minimal demands on time or effort, and focus on making motivational support available at any time. Interventions providing motivational support could lead to improvements in self-efficacy, an important factor in any positive behaviour change (Walpole et al, 2011). Tucker et al (2016) found an increase in physical activity in nursing staff following a workplace intervention that offered personalised health coaching via text messaging and a variety of activities with other staff that fitted into the working day, including workstation treadmill, stair climbing and walking meetings.

Concerning the impact of physical activity on sleep quality, exercise positively influences sleep through various physiological and psychological mechanisms, as described by Chennaoui et al (2015). On the other hand, there is a bidirectional relationship between exercise and sleep, as lowered physical activity levels lead to poor sleep and vice versa (Kline, 2014). The findings indicate that more than one in three students did not get at least 7 hours of sleep per night. The lack of sleep, among other factors, could provide a plausible explanation for poor dietary choices within the current sample. In support of this view, the level ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating stomach-derived peptide (Cummings and Foster, 2003; van der Lely et al, 2004), increases and the level of leptin, an appetite-suppressing, adipocyte-derived hormone (Zigman and Elmquist, 2003), decreases during chronic sleep deprivation (Taheri et al, 2004).

Student nurses' perception of their dietary choices were mostly good since over 60% reported that they followed a healthy diet. However, more than two-thirds did not consume the recommended daily amount of fruit and vegetables, and nearly half ate food high in fat and sugar daily. Marquis (2005) speculated that student nurses over-rely on convenience foods because of heavy study schedules and financial restraints. This is in line with the current findings, as the most important factor for consuming the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables was the price, followed by accessibility to buy these foods at the university or work placement. There are facilities to support exercise and cafes that serve healthy food with a good variety of fruit on offer. However, preparation is key because, during a busy day on campus or work placement, some students may not have enough time to make the use of these facilities.

When we questioned the second cohort of nursing students, it became clear that more than half of them were not satisfied with their lifestyles and would like to have a healthier diet and better exercise regimen. The most reported barrier to these behaviours was a lack of motivation, followed by lack of time and a busy lifestyle. These results are consistent with the previous research run with cohorts 18 months previously.

Further exploration revealed that to achieve the goals they needed financial, professional, personal and motivational support, and better time management skills. Although the majority of student nurses did not exceed the recommended weekly allowance of alcohol consumption, some displayed typical binge drinking behaviour (four or more drinks for women; five or more drinks for men), and over one-third (40%) admitted to drinking more than five drinks on one occasion.

The reported prevalence of binge drinking was much higher compared to the general population for this age group, where rates are 29% of men and 26% of women (Office for National Statistics, 2013). This behaviour might be typical of university students in general (Dantzer, et al, 2006; Howell et al, 2013), but these findings may not be desirable for the future workforce of the NHS, who are often expected to act as role models (Blake et al, 2011).

Limitations

The authors are aware that this research has limitations. Only one-third of student nurses invited to take part in the research completed the online survey, so the results may not be representative of the entire nursing population at the University of Plymouth; little is known of the health behaviour among the non-respondents. Nevertheless, a large number of student nurses reported engaging in negative health behaviour.

Conclusion

This study suggests that student nurses engage in poor health behaviour despite their knowledge about the negative health consequences. It indicates the need for a more effective intervention that focuses on motivational support and addresses barriers to healthy lifestyles.

An intervention needs to be cost-effective and accessible at any time while remaining convenient to this population, who feel under pressure in terms of time and money, so are unlikely to take on the additional effort of attending classes or training courses beyond their curriculum.

It is difficult to address all barriers identified within this research, but the use of health-related apps to get inspiration for meal ideas, planning, exercise plans and shopping lists, together with personal motivational support, could be the solution. With more than half of the respondents already using some form of smartphone app to help them improve their diet or exercise, an eHealth app incorporated into training about patients' weight management could be an acceptable and effective means of achieving and sustaining positive behaviour change, as well as meeting an educational objective.

The challenge now is to develop an intervention that incorporates these factors and provides the motivational support that is currently lacking.

KEY POINTS

- Preregistration student nurses tend to be overweight and have unhealthy lifestyles, despite their knowledge about the negative health consequences

- Lack of motivation and time are the most frequently reported barriers to following a healthy lifestyle

- There is the need for a more effective intervention that focuses on motivational support

- An eHealth intervention could be an acceptable and effective means of achieving and sustaining positive behaviour change

CPD reflective questions

- Is knowledge about a healthy lifestyle sufficient to live a healthy lifestyle?

- What are the two most frequently reported barriers to a healthy lifestyle? Why do you think people mention these two issues?

- Is the problem of overweight in the nursing profession caused by the pressures of the job?

- What advantages would an eHealth app have in achieving a healthy lifestyle?