A large, combined acute and community trust has successfully introduced the professional midwife advocate (PMA) role using the Advocating and Educating for QUality ImProvement (A-EQUIP) model (NHS England/NHS Improvement, 2021a) and progressed to adopt the role in nursing, the professional nurse advocate (PNA). Locally, the PNA role is underpinned by a higher education institute (HEI)-led training programme. Currently, there is limited practical guidance for the effective implementation of the role in practice.

Background

Clinical supervision plays an important role in the provision of quality nursing care and has been promoted for nurses in the NHS for some years (Driscoll et al, 2019). The practice is associated with positive patient outcomes (Snowdon et al, 2017) and can help mitigate the impacts of stresses on the nursing role (O'Connor et al, 2018). A variety of models for workplace supervision have evolved, yet uptake has been variable. Despite the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) advocating clinical supervision for all registrants (NMC, 2018), consistent barriers to implementation persist, including a lack of clarity in relation to which model of clinical supervision has better outcomes (Pollock et al, 2017; Driscoll et al, 2019). Many studies that report the benefits of clinical supervision fail to specify the use of a particular model (Fowler, 1996;Cheater and Hale, 2001; Edwards et al, 2005; Puffett and Perkins, 2017). There is also a lack of delineation between clinical supervision and other professional models of support, for example, managerial, and potential confusion between clinical supervision models and clinical supervision functions that can lead to poor quality supervision (Cutcliffe et al, 2018). These barriers have been exacerbated by personal factors such as fear of change, lack of confidence, knowledge, skills or understanding, and failure to recognise the need for clinical supervision, as well as organisational factors, including poor quality training for supervisors, lack of support and time (Ariss et al, 2017).

Implementation of the PNA role and the A-EQUIP model in nursing is relatively new. Midwifery led the way in developing this new employer-led professional model of supervision (Ariss, 2017). The A-EQUIP model, deployed by professional midwifery advocates (PMAs), was initiated by NHS England in 2017 in response to concerns over the traditional approach to midwifery supervision (Kirkup, 2015). The model aims to promote education and development, build personal and professional resilience using a restorative approach, enhance care quality and support preparedness for appraisal and professional revalidation (Ariss et al, 2017). By using the model to empower and develop staff, improving quality of care becomes an integral part of everyone's job (Mahachi, 2020a). The principles and philosophy of the model are deemed transferable to other professional groups (Whatley, 2022). The intention was to have 5000 PNAs, across all specialties in England by April 2022 (May, 2021). National and local implementation was guided by the provision of PNA training, funded by Health Education England (HEE).

Methods

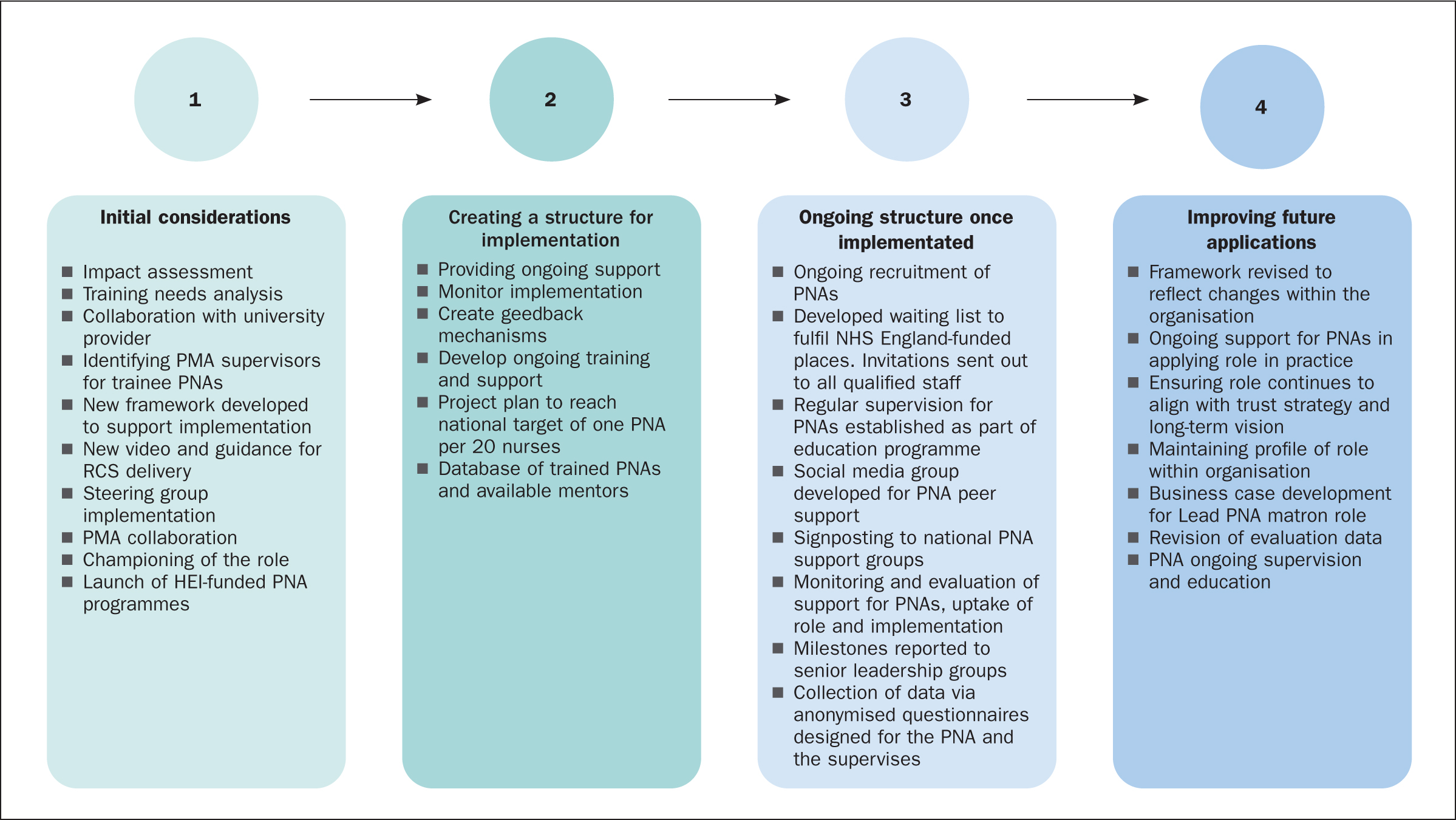

A recognised quality implementation framework (Meyers et al, 2012a; 2012b) was used to retrospectively appraise and represent locally derived strategic activities for successfully implementing the PNA role in a combined acute and community NHS trust in England. Meyers et al (2012a) developed the framework from a synthesis of 25 frameworks. Four critical steps were identified for implementation:

- Initial considerations regarding host settings

- Creating a structure for implementation

- Ongoing structure once implementation begins and

- Improving future applications.

The framework builds on previous work by focusing on specific actions (Meyers et al, 2012a). This approach has the potential to increase stakeholder awareness of the necessary steps for quality improvement, facilitate consultation with key stakeholders and ensure the process is formally documented. Experience in quality implementation is needed to adhere to the framework (Meyers et al, 2012b), this may limit its utility.

Phase one: initial considerations regarding host settings

Initial considerations

Following the successful implementation of the A-EQUIP model and PMA role locally, the trust introduced the role to registered nurses in 2020. The organisation had 3500 nurses who could benefit from implementation of the PNA role, which has the potential to impact on recruitment, retention, staff engagement, compassion fatigue and sickness absence (Critical Care National Network, 2022).

Key structures for implementation

To support implementation, a framework was developed (The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, 2021; Whatley, 2022). This set out aims, objectives, and a vision for the role and provided a clear implementation plan. The framework also described the necessary support and preparation for PNAs, how staff might access supervision and trust processes for monitoring and evaluation. A clear vision is a prerequisite for successful quality improvement (Backhouse and Ogunlayi, 2020). Resources developed included session templates to guide restorative clinical supervision sessions and a brief video (Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, 2021). The template for restorative clinical supervision aimed to support PNAs in delivering sessions as intended and ensure implementation fidelity (Lorencatto et al, 2013).

A steering group, the driving force for adoption, was set up to oversee the introduction of the PNA role. A lead PNA role was not implemented at this stage. Responsibility for driving the innovation was shared among the group members; these included staff from education and research. There was also PMA and trainee PNA representation. Steering groups have an important role in overseeing the process and issues during implementation. Members should have both authority and credibility and effectiveness will depend on members' active participation and commitment (Health Care Improvement, 2021). The PNA steering group supported successful implementation; it had a shared aim and ensured the right people were involved, such as nurses from the executive team and education team alongside active PNAs and PMAs. This mix of individuals helped ensure strategic direction and a balance between those who can make decisions and those who can complete actions.

Fostering support from within the organisation

Commitment from senior nurses within the organisation ensured that the innovation had leadership with decision-making power. Commitment was engendered through the PNAs, who emphasised the need for the intervention within the organisation, this served to generate ‘buy-in’ from stakeholders (Meyers, 2012b). Meyers et al (2012b) suggested implementation will only be successful if the workforce or other stakeholders are convinced that the innovation is needed. PNAs engaged with frontline staff and championed the role within their areas, with some colleagues inspired to undertake the HEI-funded PNA programmes.

Preparation for PNAs

During the initial implementation phase, a mix of senior nurse leaders from various specialties nominated themselves to undertake the training in eight stages at a time. Training involves a Level 7-accredited programme that includes practical exposure to the role, as well as education and critical analysis of the A-EQUIP model. Initially delivered by a local HEI, it is now part of the HEE nationally sponsored PNA training programme. In this early phase, established PMAs were available to support PNAs in practice.

Phase two: creating a structure for implementation

Structures for implementation

Successful implementation was ensured by having a robust framework (The Royal Wolverhampton Trust, 2021) in place and steering group members with the relevant expertise. This ensured three important tasks were achieved in the second phase: providing ongoing support, monitoring implementation, and creating feedback mechanisms (Meyers et al, 2012a).

Ongoing education

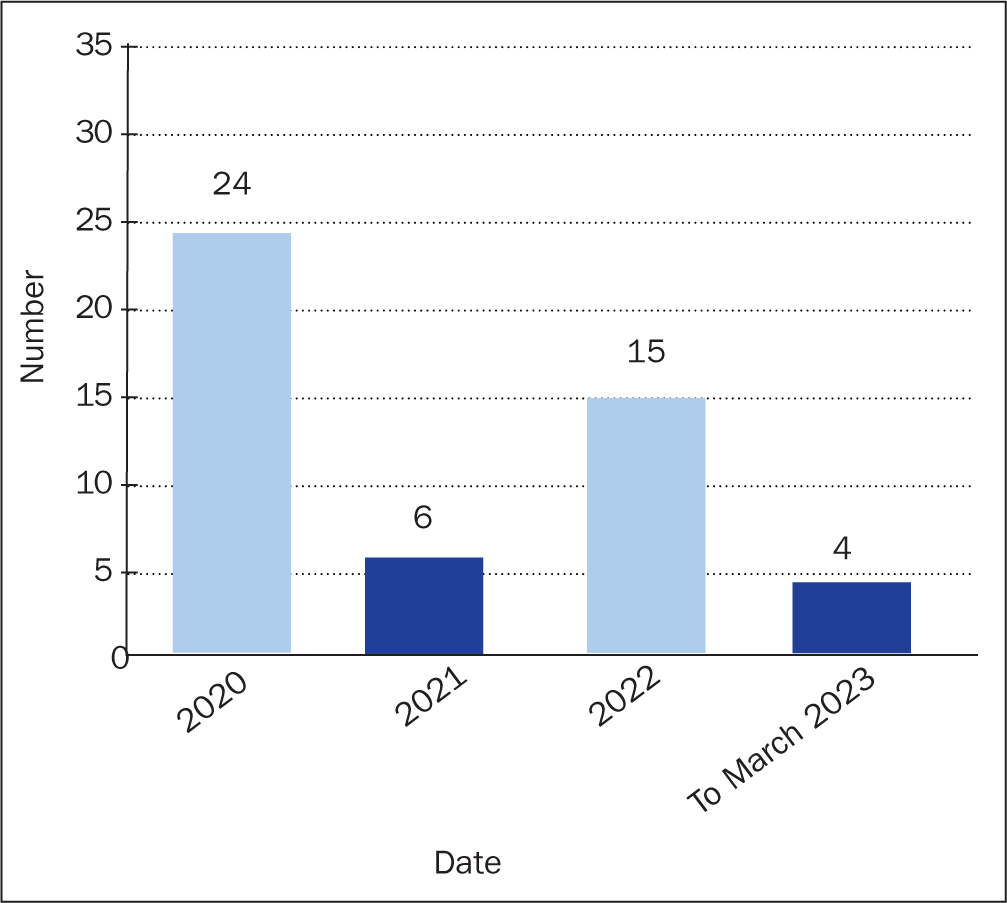

The organisation has pledged that all nurses attending the course will be given adequate time to attend the training and complete study-related activities, with their positions backfilled. The target for implementation mirrored the national target of one PNA trained per 20 nurses (NHS England, 2021a). In December 2022, 46 registered nurses in the trust had completed the PNA training, see Figure 1.

PNA students are centrally assigned a trained PNA or PMA mentor from within the trust. This mentor is encouraged to demonstrate their practice, receive restorative clinical supervision from the student and offer feedback and supervision to develop the necessary PNA skills. Members of the steering group meet with senior sisters and matrons, following each student's completion of the course, to launch the role in their area following completion of training.

Phase three: ongoing structure once implementation begins

This phase is ongoing and involves three important tasks: providing needed ongoing technical assistance, monitoring ongoing implementation and creating feedback mechanisms.

Ongoing recruitment of PNAs

Funding for the PNA training is received intermittently from NHS England. Invitations are sent out to qualified staff via the education team when funding becomes available.

Support in the role

The PNA framework (The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, 2021) acts as a handbook for those trained to undertake the role. Support for PNAs continues to be available via PNA mentors, regular supervision, and a social media group for PNAs to share ideas and learning and offer peer support. All PNAs also have access to a national PNA network.

Measures of success

The PNA steering group is responsible for the strategic and operational management of the PNA role. The group monitors the effectiveness of support for PNAs, uptake of the role and ongoing implementation. Milestones are reported to the senior nursing, midwifery and health visitors leadership group as part of the trust's wider nursing and midwifery strategy (The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, 2022).

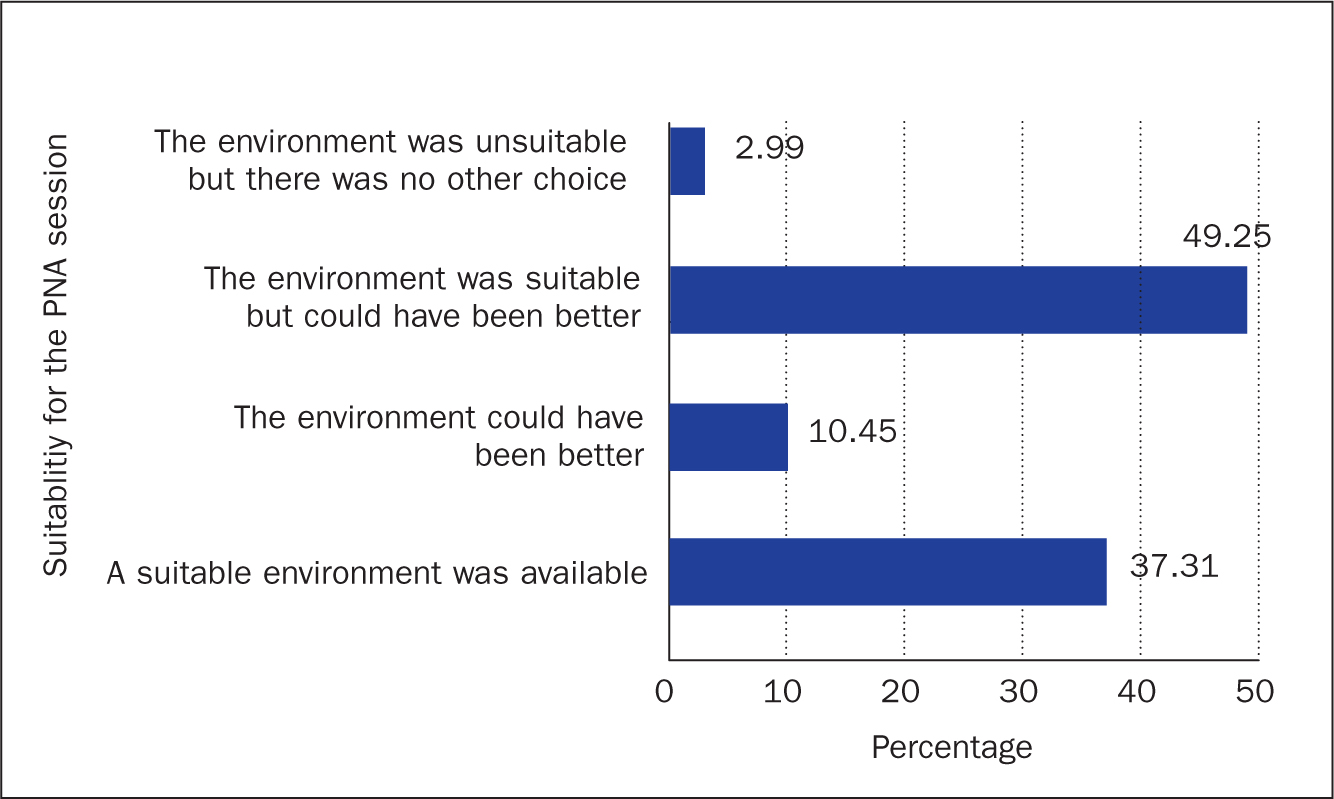

The organisation requires data to demonstrate the role's efficiency and inform future applications. Two anonymised questionnaires have been designed for the PNA and the supervisee. This is available via a QR link, PNAs are asked about the suitability of the environment, the session's theme, and outcomes. For supervisees, questions focus on processes for arranging the session, and whether it met their needs and access in the future. See Figure 2 and Table 1 for PNA supervisor outcome data 2020-2023 and Table 2 for PNA supervisee outcome data.

Table 1. Professional nurse advocate supervisor feedback September 2020 to January 2023

| Supervisor session theme | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Career related | 7.1% |

| Education/training related | 10% |

| Emotional distress (not work related) | 12.9% |

| Health and wellbeing | 15.7% |

| Professional relationships | 18.6% |

| Emotional distress (work related) | 26.4% |

| Safeguarding | 4.91% |

| Other (setting up a new service, service improvement, staff dealing with grief and loss and working through a global pandemic) | 2.9% |

Table 2. Professional nurse advocate supervisee questionnaire feedback September 2020 to January 2023)

| Based on your experience of professional nurse advocate supervision, which of the following would you say is true? (Tick all that apply.) Professional advocate supervision: | Percentage of those in agreement with the statement |

|---|---|

| Provides an emotionally safe space for discussion | 94.44% |

| Shows concern for staff wellbeing | 92.59% |

| Reduces work-related stress | 68.52% |

| Encourages critical reflection | 81.48% |

| Aids professional development | 64.81% |

| Develops self-esteem | 72.22% |

| Supports staff contribution to quality care | 61.11% |

Phase four: improving future applications

This final phase involves retrospective analyses and self-reflection with feedback from implementers to identify strengths and weaknesses that occurred during implementation. Members of the steering group engaged in the self-reflection process. Several themes emerged, these included: revising the framework; challenges in implementation, with the subthemes inconsistencies in training, maintaining the profile of the role, and time and space for sessions; criteria for success; and measuring success. These are discussed below.

The framework, constructed in phase 1 and repeatedly revised to reflect changes within the organisation (Whatley, 2022), supported PNAs in applying the role in practice; this was critical to success and key to ensuring consistency in implementation (NHS England/NHS Improvement, 2021b). The steering group also played a crucial part in phase 1 (NHS England/NHS Improvement, 2021b). Key stakeholders from nursing and education with a deep understanding of the organisation and the PNA role ensured that implementation was aligned with the trust strategy and long-term vision. It also provided an opportunity to identify what was going well and to solve any problems.

Challenges to implementation in phase 2 included inconsistencies in the provision of training and assessment criteria. The trust compensated with local mentorship to bridge the skill gap. There have also been discrepancies in the number of credits awarded, with the potential to impact individuals hoping to gain credits against a master's degree. Phases 2 to 3 of the quality implementation framework demonstrated the importance of maintaining the profile of the role and ensuring staff are informed about its value and purpose. Some PNAs reported feeling confused about the role or underestimated the time commitment, resulting in a high attrition rate. Other challenges included securing enough time for the role and provision of a protected quiet space for PNA sessions. This suggests PNAs must be adequately prepared, confident that they will be supported to undertake the role, and in a position to support staff. Connecting PNAs for support via the social media platform, mitigated against some of these challenges and proved invaluable (NHS England/NHS Improvement, 2021b).

PNAs mainly undertake the role in their clinical areas or areas without a PNA. It has been noted that those working in corporate services are particularly good at flexibly supporting a range of areas, often where there have been critical incidents or large areas such as intensive care and acute medical units requiring additional support. The organisation is planning to appoint a senior PNA lead. A lead PNA is expected to raise the profile and increase understanding of the role within the organisation. It has been identified as a criterion for successful implementation in some organisations in an unpublished report in 2022.

Measuring success has been a significant challenge in phase 3. Further work is required to ensure the collection of meaningful and timely evaluation data. This is required to demonstrate the value of the role and measure outcomes, which are expected to be: improved retention, reduced sickness; improved team working/civility; and improved professionalism and reflective practice (Whatley, 2022). See Figure 3 for a project flow chart.

Discussion

Leadership for change

The PNA is an employee-led leadership role (NHS England/NHS Improvement, 2021a). PNAs can support a culture of belonging and autonomy in which all voices are heard and staff at all levels are empowered to contribute to innovation, quality improvement and change (West et al, 2017; May, 2021). PNAs adopt ‘servant leadership’, centering on listening to, building trust with and empowering colleagues, with the aim of encouraging self-actualisation and positive attitudes to work and ensuring that this is sustained (Mahachi, 2020b). Leading change and improvement can be challenging in complex healthcare settings such as the NHS (West et al, 2017). Therefore, leaders must have the appropriate knowledge and skills around leading improvement, engaging others, creating a shared vision, and developing an inclusive and supportive culture (NHS Confederation, 2021).

The implementation demonstrated a high level of strategic leadership, an essential skill for the management of change (Senge, 2006). If effective leadership is present, it can be the catalyst for innovation and collaboration among nurses (Afsar, 2016), while transformational leadership can provide the nurturing and necessary culture required for knowledge-sharing behaviour and the enablement of innovation (Lee et al, 2018).

Sustaining early post-implementation success

Sustaining early success demands continuous effort in the post-implementation phase (Ament et al, 2017), with support from all leaders across the organisation identified as particularly important (Fleiszer et al, 2015) together with accessible support from peers, embedded within the organisation (Webster et al, 2020). This may be challenging given the budget-constrained healthcare system. However, there is commitment to workforce wellbeing and recovery post-pandemic (NHS Confederation, 2021). Indeed, the PNA role has been recognised as an essential aspect of the post-COVID-19 pandemic restorative period, with the leadership elements of the role identified as necessary for supporting workforce health and wellbeing and promoting resilience within individuals and nursing teams (Keele University, 2022).

Practical barriers to implementation of restorative clinical supervision sessions, such as accessing a quiet space, must be considered for future application. A supervision session's location and timing are essential for success (Rouse, 2019). The issues of protected time and space for PNAs and staff to hold sessions were highlighted by all eight providers in the West Midlands evaluation of the PNA role in an unpublished report in 2022 and have been highlighted previously concerning the PMA role (Rouse, 2019). There is a risk that, due to operational pressures, support for the model could be deprioritised, despite evidence suggesting, over the longer term, that supervision enhances patient and staff outcomes (Carter, 2022). Sustainability challenges appear to be mirrored across NHS organisations (Ament et al, 2017).

From a long-term perspective, continuous data collection, and timely communication of findings to stakeholders involved in the post-implementation phase, have also been shown to encourage staff to sustain behaviour changes (Ament et al, 2017). To increase commitment to data quality, it is essential those involved understand the importance of data collection for decision-making purposes (Hansen et al, 2007).

Conclusion and recommendations

A QIF framework can provide a clear path for successful implementation of the PNA role and A-EQUIP model. PNAs should be supported to develop a culture of effective supervision within their own organisation. Recommendations include involving key stakeholders in the early stages and ensuring staff are prepared and adequately informed about the role and equipped with the necessary leadership skills to drive change and overcome barriers to implementation. The experience of this trust is that committed organisational leadership, combined with the co-ordination of the introduction and support of the PNA role using a quality implementation approach, is critical to success.

KEY POINTS

- Professional nurse advocates (PNAs) should be supported to develop a culture of effective supervision within their own organisation

- The role requires effective leadership skills to lead improvement, engage others successfully, create a shared vision, and develop an inclusive and supportive culture

- Commitment is required from senior nurses within the organisation to promote the value of the PNA role and support effective implementation

CPD reflective questions

- How can the professional nurse advocate (PNA) role be implemented in your area, using a quality improvement approach?

- How can you mitigate against the barriers to implementing the PNA role in practice?

- What key skills are required for the PNA role?