COVID-19 has caused significant upheaval to the global population. For many years, an influenza-like pandemic was predicted, with the suggestion that healthcare systems should be prepared, because this would be difficult to contain and would affect millions of individuals (Maunder et al, 2008).

It is widely documented that health professionals have experienced anxiety and distress throughout previous pandemics (Chong et al, 2004; Wu et al, 2009; FitzGerald et al, 2012; Mohammed et al, 2015). It has also been identified that health professionals on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic are at increased risk of stress, burnout, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Hedderman et al, 2020; Supady et al, 2021).

During previous pandemics health professionals were redeployed to cope with demand. However, experience during the H₁N₁ influenza outbreak highlighted an increased need to improve redeployment strategies because late notice of redeployment was found to negatively affect departments, staff and functioning ability (Considine et al, 2011; O'Sullivan, 2023). Nurses who have experienced redeployment have described it as stressful, leading to feelings of disempowerment, fear, insecurity, anger, depression and betrayal (Blythe et al, 2001). The consequences of redeployment appear to be largely ignored, with the main focus placed on improving operational structures, leaving health professionals feeling unable to accomplish career goals, while long hours in demanding areas has led to exhaustion and increased absenteeism (Blythe et al, 2001; Considine et al, 2011).

The rapid and unpredictable spread of COVID-19 found that health services were unprepared, and it was problematic for the rapidly restructured services to ensure safe staffing (Foster, 2020; Supady et al, 2021). Clinical staff were redeployed to unfamiliar areas, leading to difficulties in creating effective working relationships with already established teams (O'Sullivan, 2020). It is widely recognised that nurses experience traumatic events during a pandemic, and that without their usual support group their mental health suffers (O'Sullivan, 2023). During the first wave of the pandemic, 10-15% of health professionals were self-isolating or off sick (Kendall-Raynor, 2020). This forced the NHS to redeploy staff to new areas, bring back staff from retirement or upskill students to join the workforce (Kendall-Raynor, 2020).

The Royal College of Nursing Research Society steering group explored the real-time impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on nurses and midwives across the UK (Mitchell, 2020; Stephenson, 2020). The ICON study (Impact of COVID-19 on the Nursing and Midwifery workforce study) involved completing a survey on three separate occasions and included questions around health services pre-COVID-19, the impact of the COVID-19 peak, and recovery post-COVID-19 (Gilroy, 2020; Mitchell, 2020). Results to date indicate that over half of those surveyed were afraid of catching COVID-19 and were worried about the risk to their friends and family (Mitchell, 2020). Sixty-two percent of respondents felt a lack of, or inadequate redeployment training; while feelings of anxiety, depression, stress, and emerging signs of PTSD were experienced (Gilroy, 2020). Only 12% reported accessing NHS wellbeing resources (Gilroy, 2020; Kendall-Raynor, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic surpassed previous outbreaks and had the highest prevalence of psychological distress in health professionals (Dong et al, 2020). Seventy per cent of frontline staff reported increased personal stress during the pandemic and, as in previous outbreaks (Ebola, SARS-COV and H₁N₁ influenza), staff reported high levels of anxiety, stress and depression (FitzGerald et al, 2012; Liu et al, 2020; Supady et al, 2021). This pandemic led to global panic and uncertainty, however due to pressures faced by health professionals and the strain on health services, it was inevitable that frontline health professionals would see far-reaching effects on their health and wellbeing (Dong et al, 2020). It is essential that policies are in place to reduce these effects and continue to protect frontline workers' physical and mental health (Dong et al, 2020; Supady et al, 2021).

Restructuring in response to need

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a rare multisystem disease and care should be provided at specialist CF centres by multidisciplinary teams. Specialist care is required as CF is a life-limiting disease that occurs in 1 in 25 000 live births in the UK (Cystic Fibrosis Registry, 2019; Davis et al, 2020).

The Royal Brompton Hospital (RBH) is a specialist cardiac and respiratory hospital. As well as having one of the largest adult CF centres in Europe, it is also one of five nationally commissioned extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) centres (Bleakley et al, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic led to RBH increasing ECMO capacity, placing an increased burden on critical care (NHS England, 2020; Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust, 2020). During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic RBH became a dedicated COVID-19 centre, leading to service restructuring and staff redeployment to provide the necessary space and staffing to accommodate referrals from other hospitals (Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust, 2020). Due to the service restructure, all nursing staff on the specialist adult CF ward were informed of the ward closure on the 26 March 2020, with immediate redeployment to a COVID-19 high-dependency unit (HDU) stepdown ward.

The effects of redeployment on specialised nursing teams caring for specific long-term conditions, such as CF, during the COVID-19 pandemic has yet to be explored.

The aim of this study was to evaluate nurses' wellbeing following redeployment from a specialist adult CF ward to a COVID-19 HDU-stepdown ward during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study intended to review and highlight the experiences of redeployment and the effects on staff wellbeing to ensure that protocols and procedures are optimised so that both healthcare services and workers are prepared for and supported in future pandemics.

Methodology

Purposive sampling was used to recruit nurses redeployed from the CF ward to the COVID-19 HDU-stepdown environment. All nurses working on the CF ward at RBH who were redeployed to a COVID-19 environment were included. Those who had worked on the CF ward but deployed to an alternative situation were excluded.

A mixed online survey, consisting of both open and closed questions, was based on the ICON study, with the survey questions formulated on the basis of the preliminary results from this study, previous literature, and informal feedback from ward staff. Due to time constraints, one survey with three sections consisting of both open and closed questions was designed, as outlined below. Participants had 4 weeks to complete the survey.

Part 1

The first section collected nurses' demographic data, including how long they had worked on the CF ward, which was followed by open-ended questions asking about previous jobs and reasons why they worked on the CF ward.

Part 2

This section explored how nurses felt during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, including how they felt when they were told that the CF ward was closing (they were asked to select a variety of positive and negative feelings); whether they had received training for their new role; whether this was adequate; and whether they felt they had adequate support from senior staff and management. Further questions included opinions about training, support and information needed to feel comfortable in their new role. Based on previous pandemic literature, participants were given a list of factors and asked whether any had influenced their practice during the pandemic. Finally, participants were asked if they had accessed any wellbeing services or used any other coping strategies during the pandemic and, if so, to outline which ones.

Part 3

This final section explored how participants viewed their role following the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, including key differences between their current role and previous role and, finally, the nurses were asked how they saw their roles and career plans following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis model and descriptive statistics were chosen as methods for data analysis. Thematic analysis was chosen because it can be performed with small data sets and there is an element of flexibility, with the choice of data collection method and sample size – all key factors required to combat the fluidity of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased requirements on healthcare staff during the pandemic (Braun and Clarke, 2013). Thematic analysis focuses solely on data analysis, which allows for free selection of data collection methods (Braun and Clarke, 2013; Nowell et al, 2017). Descriptive analysis was used as it allows for a simple assessment of numerical data and can be a useful method for summarising data collected in surveys (Fisher and Marshall, 2009).

Ethical approval and consent

Using the NHS Health Research Authority decision tool this study was classed as a service evaluation. Ethical approval was not therefore required. Following advice from the Research and Development office of RBH this study was therefore not registered with the NHS HRA.

Participants were asked for consent before they completed the survey. If they declined, they were unable to proceed and respond to the survey questions on the online platform.

Results

Demographics

At the point of closing the survey the response rate was 86% (n=23); one participant declined to consent to take part in the study. In total, 78% of the nurses identified as female, the age range was 21–60 years, and ethnicity included White/White British, Asian/Asian British, Black/Black British. Sixty-one percent had previous nursing experience prior to starting work on the CF ward, and time on the CF ward varied from less than 1 year to 21 years (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics of participants who responded to the survey

| Demographics | Number of respondents (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 5 (22) |

| Female | 18 (78) | |

| Age | 21-30 years | 8 (35) |

| 31-40 years | 6 (26) | |

| 41-50 years | 6 (26) | |

| 51-60 years | 1 (4) | |

| >60 years | 2 (9) | |

| Ethnicity | White/White British | 14 (61) |

| Asian/Asian British | 5 (22) | |

| Black/Black British | 4 (17) | |

| Time spent working on CF inpatient ward | <1 year | 2 (9) |

| 1-2 years | 4 (17) | |

| 2-3 years | 2 (9) | |

| 3-4 years | 3 (13) | |

| 4-5 years | 1 (4) | |

| 5 years | 2 (9) | |

| 7 years | 1 (4) | |

| 10 years | 3 (13) | |

| 11 years | 2 (9) | |

| 16 years | 1 (4) | |

| 20 years | 1 (4) | |

| 21 years | 1 (4) | |

| Previous nursing role prior to the CF inpatient ward | Yes | 14 (61) |

| No | 9 (39) | |

Part 1

When asked why they had chosen to work on the CF ward participants' reasons included: enjoyment of the nurse–patient relationship (48%), interest in respiratory nursing and CF care (52%), and the specialist nature of their role and hospital (35%).

Part 2

Thematic analysis was used to explore the data collected in part 2 of the survey. From this, three key themes emerged: redeployment anxiety, lack of organisational preparedness, and newfound team working and support.

Redeployment anxiety

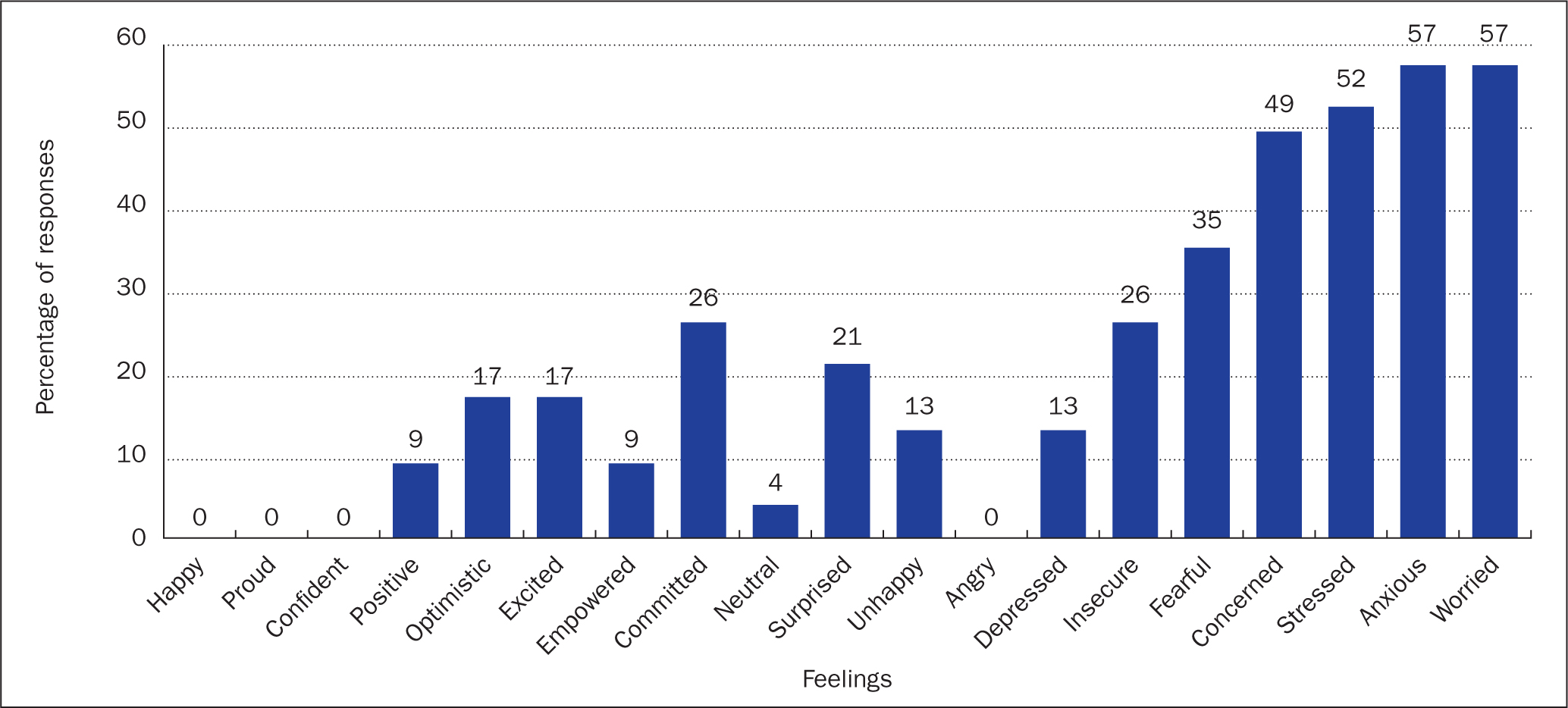

Participants were asked how they had felt when the CF ward was closed and they were redeployed to a high-dependency COVID-19 environment (Figure 1). Fifty-seven per cent reported they had felt anxious, 57% that they had been worried and 52% that they felt stressed. These feelings were associated with the rapidity of the change: for example, participant 1 reported that the change ‘was sudden’. The nurse reported having feelings of doubt, inadequacy, surprise and confusion. Participant 16 stated: [there was] ‘no choice but to go with the move or to resign’. Although most of the nurses' feelings were related to anxiety and fear, some expressed commitment and open-mindedness to the change, while others saw it as an opportunity to help patients with COVID-19.

Lack of organisational preparedness

This was a repeated theme, leading to anxiety about being unaware that a change in role and location was going to occur. Participant 4 reported they had ‘not been briefed by management on the change’. This theme was common, with the nurses reporting across multiple answers that there had been poor communication from management. For example, at times communication was ‘appalling and fragmented’, according to participant 15, with participant 21 citing poor communication and a lack of presence or support from senior hospital management as ‘contributing to staff stress and anxiety’. Others comments included:

‘No support from management as it appeared that they themselves did not know what was happening.’

Participant 10

[It was more like the] ‘blind leading the blind.’

Participant 15

Training and support

The majority of respondents (74%) reported that they had received training for their new role. This varied and ranged from tracheostomy training to general COVID-19 competencies (Table 2). Despite this, only 33% thought the training had been adequate, for example participant 8 stated: ‘I thought the training should have been more intense.’ Participant 3 acknowledged the pandemic was an ‘unexpected event’, while others stated:

Table 2. Redeployment training provided to participants

| Number of respondents (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Did you receive training for your new role on the COVID-19 HDU? | Yes | 17 (74) |

| No | 4 (17) | |

| No response | 2 (9) | |

| If yes, what training did you receive?* | Tracheostomy training | 10 (59) |

| Proning training | 4 (24) | |

| Electronic documentation training | 1 (6) | |

| Arterial line training | 5 (29) | |

| Mechanical ventilation training | 3 (18) | |

| Donning and doffing training | 3 (18) | |

| Non-invasive ventilation training | 1 (6) | |

| General COVID competencies | 1 (6) |

‘It felt like being shown an egg and then being expected to cook a three-course meal without knowing how to turn the oven on.’

Participant 16

‘I felt inadequate to carry out specific tasks.’

Participant 11

Some reported that they were able to rely on their previous work experiences. For example, participant 4 responded: ‘Due to my previous experience I was able to adapt easily.’ This allowed the nurses who had some relevant experience to adapt quickly and easily; however, others felt disadvantaged due to their lack of experience. Overall, there was wide agreement that the training and information provided had been too much to absorb in a short space of time and most learning occurred on the job, as illustrated by one of the nurses: ‘

‘I feel that a lot was learnt on the actual shift.’

Participant 15

Newfound teamworking and support

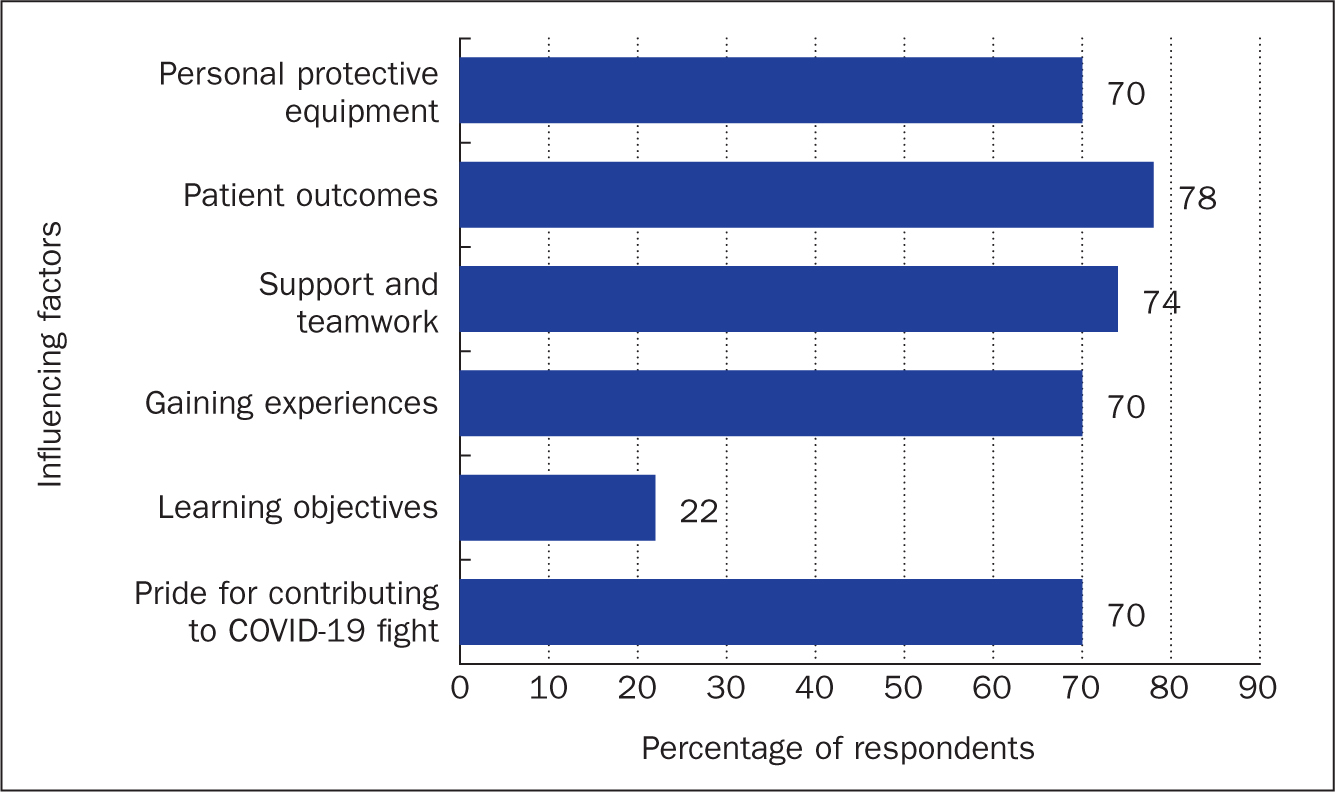

Although participants identified a clear lack of organisational preparedness and support from senior hospital management, there was consensus that hands-on senior staff and management were doing their best. The view of participant 16 was that ‘the immediate hands-on management were brilliant’. When asked which factors had influenced their nursing during this time (Figure 2), 74% reported support and teamwork:

‘Those involved in directly caring for patients generally worked well together.’

Participant 3

Despite identifying a lack of adequate training, the nurses acknowledged and accepted the challenges faced by COVID-19 and supported each other by developing learning and skills while working together. Experienced nurses supported junior staff who reported that this helped them to feel positive.

Part 3

COVID-19 pandemic influences the experiences of redeployment

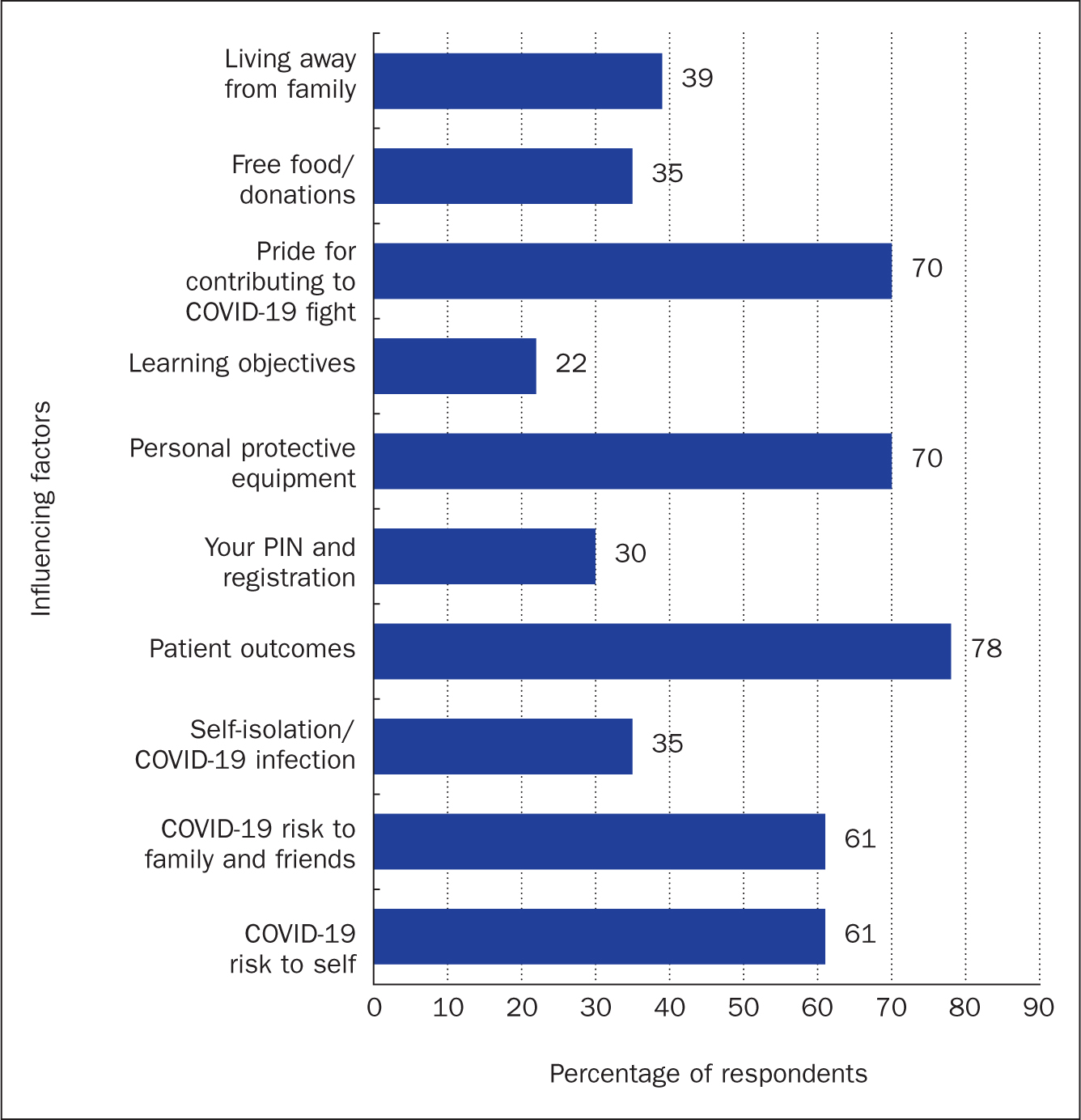

Just under two-thirds (61%) of respondents said that the risk of COVID-19 to themselves, their family and friends had influenced how they had felt and made them ‘feel anxious about potentially being infected by COVID-19 and bringing it home’ (participant 5) (Figure 3). Participant 2 explained that they were feeling ‘overwhelmed and sad’, while participant 21 stated: ‘I could not cope with another wave.’ Despite this, 70% reported that had taken pride in their contribution to tackling COVID-19, with 78% stating that patient outcomes had affected how they felt during the pandemic (Figure 3).

‘I felt proud working for the NHS and being able to contribute during this pandemic.’

Participant 8

Although 75% reported having negative feelings, only 14% accessed wellbeing services during the pandemic, with participant 10 stating: ‘I didn't know there were any available.’ Of those who had sought some sort of support, one had spoken with a psychologist and another had used meditation; others had used free food and meals donated to the hospital, practised yoga, talked to family and friends, and used alcohol. Some took advantage of a respite lounge provided in the hospital, and yet others used faith and prayer; some coped by adopting a healthy diet and lifestyle.

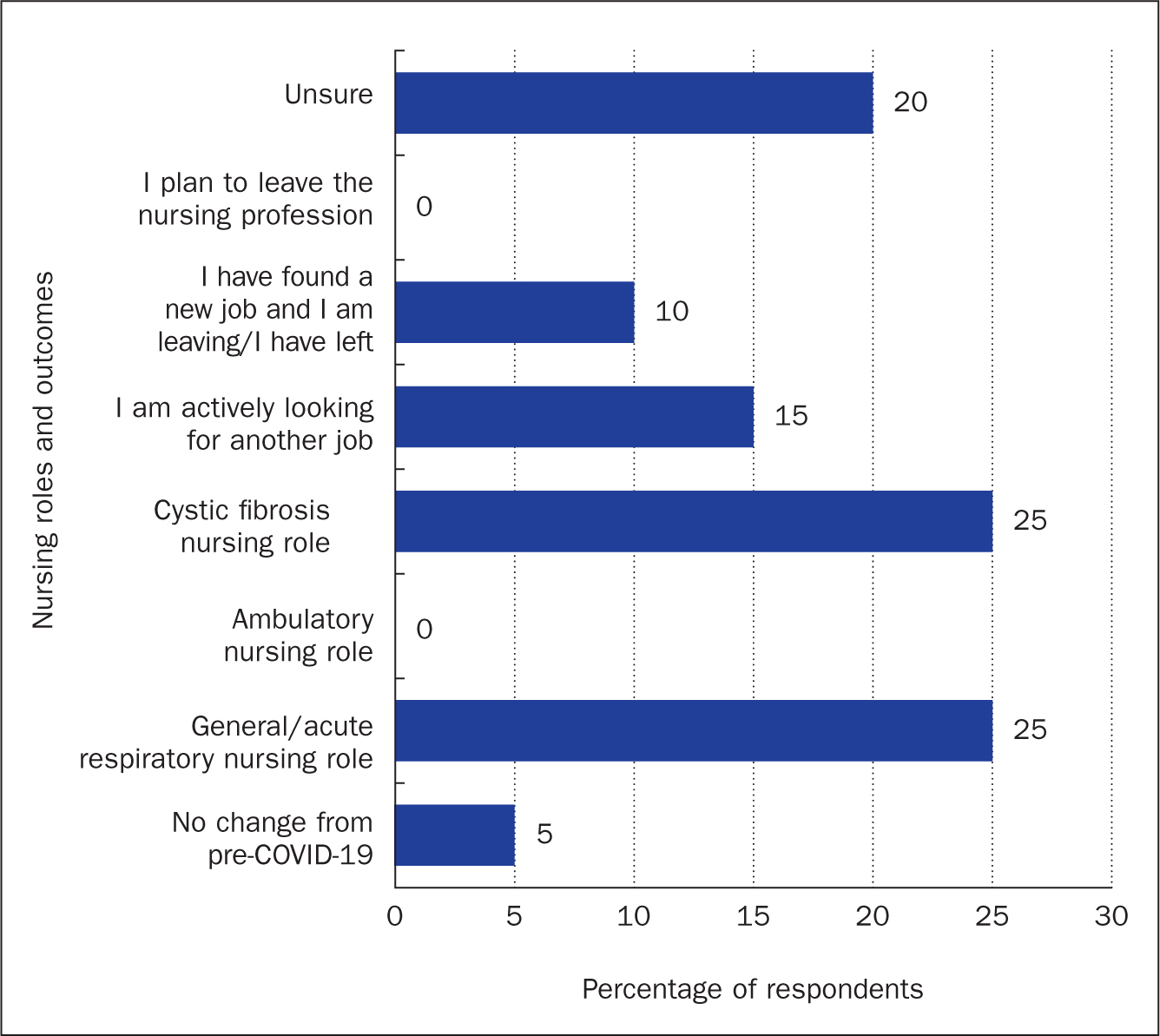

Finally, participants were asked how they viewed their nursing role post-COVID-19 (Figure 4). One-quarter (25%) thought that they would return to CF nursing, with the same number (25%) saying that they would prefer to move to more general or acute respiratory nursing. A further 20% were unsure about their future: one reported feeling unsure whether they wanted to remain in the nursing profession. A slightly smaller number (15%) reported that they were actively looking for a new job, while 10% had already found a new job or had left their role on the CF ward at RBH.

Unhappiness with changes to their role and department were given as reasons for leaving and looking for a new job, illustrated by participant 1: ‘…unhappy with the changes post COVID.’ Others wanted to leave to join an acute nursing environment, and one respondent was planning to return to their home country. Of those who intended to remain nursing in the CF specialty, reasons given included that they wanted to continue looking after CF patients:

‘I still want to continue looking after general respiratory and cystic fibrosis patients.’

Participant 6

Others stated that the COVID-19 pandemic had reinforced the importance of their role and holistic care.

Discussion

To explore how redeployment affects health professionals caring for patients with long-term health conditions, such as CF, this study sought to determine how redeployment from a specialist ward to a COVID-19 HDU affected the wellbeing of redeployed nurses. Subsequently, this is the first study, to the authors' knowledge, that investigated how redeployment from a specialist adult CF ward to a COVID-19 HDU affected nurses.

The findings of this study highlight the importance of maintaining wellbeing support for redeployed staff. Redeployment has previously been reported to cause distress and upheaval to health professionals (Ballantyne and Achour, 2023; O'Sullivan, 2023), and the results of the authors' study support this. Previous research has found that work-related stress and anxiety are compounded by redeployment (Kennedy et al, 2022; Ballantyne and Achour, 2023). These emotions are known to have negative consequences for the health and wellbeing of health professionals, while also being detrimental to health services due to the increased risk of absenteeism (Blythe et al, 2001).

This study has identified that 48% of participants had chosen to work on the adult CF ward because of the close nurse-patient relationship. This relationship is highly beneficial for both patients with long-term conditions, who have regular hospital admissions, and for nurses, as mutually caring relationships can form (Bush et al, 2015). Redeployment may cause this work pattern to break and leave the nurse at risk of burnout (Yu et al, 2016). This can be exacerbated if a redeployment is sudden and not mutually agreed between staff and management (Considine et al, 2011).

The results of this study have highlighted poor communication between senior hospital management and redeployed staff. The need for improved communication has been raised during previous pandemics, chiefly in terms of the need for the provision of effective and up-to-date information to prevent increased anxiety and confusion among frontline healthcare staff (FitzGerald et al, 2012). Poor communication can leave staff feeling alienated and isolated, and this study demonstrates that nurses did not feel appreciated or supported by senior managers, as has been reported by previous studies (Blythe et al, 2001; FitzGerald et al, 2012).

Experience from previous pandemics has underlined the need for healthcare services to be prepared for the future (FitzGerald et al, 2012). The lack of organisational preparedness and communication were also apparent in this study and undoubtedly increased the fear and stress experienced by respondents, and had a detrimental impact on their wellbeing. It has been emphasised that staff should receive early training and support to ensure rapid and smooth deployment to new areas (Foster, 2020). This study, again, has identified that this was lacking: it is clear that providing training early on in the pandemic and ensuring that support for staff was in place would have improved the experience and wellbeing of participants.

It should be noted that participants reported increased teamwork and support from frontline staff and colleagues. This is surprising, because redeployment has been shown to break down teams and act as a barrier to effective working, something that was not supported in this study, with some participants reporting that it helped bring the team closer together. Over half the participants reported feeling pride in their contribution to tackling COVID-19. It has been documented that a wartime spirit may be adopted during a pandemic (Considine et al, 2011; Gavin et al, 2020), and the participants in this study may well have assumed this attitude, with the effect of counterbalancing the full effects of redeployment). It is therefore important to consider whether the effects of redeployment were counteracted by the feelings of teamwork experienced by the nurses during a global pandemic, an issue that merits further exploration.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. First, the conclusions are not generalisable due to the uniqueness of this group of nurses, who worked in an adult CF ward at RBH and who were redeployed to a COVID-19 environment. Furthermore, the researcher (a senior nurse) was working alongside colleagues in the redeployed team: this could have been a potential barrier because participants may have not shared their true feelings. The researcher tried to mitigate this by using an anonymous online survey for data collection. Due to frontline pressures and the fluidity of the pandemic, the researcher had little time to plan and conduct the research, so the methodology was selected for convenience and speed.

Conclusion

This study examined the effects of rapid redeployment of nursing staff from a specialist adult CF ward to a COVID-19 environment. The results show that both redeployment and COVID-19 had a mostly negative impact on the wellbeing of those surveyed.

The pandemic was unexpected and the extent to which it affected the UK and the NHS was unprecedented. These results highlight that there is still a long way to go to improve pandemic planning and staff support during redeployment in such circumstances.

However, although much in this pandemic was unforeseen and unprecedented, preparedness and contingency planning should have been made following the recommendations made subsequent to both the SARS-CoV outbreak and the H₁N₁ pandemic (Maunder et al, 2008; FitzGerald et al, 2012; Gavin et al, 2020).

This study has emphasised the necessity of future planning to ensure that health professionals are appropriately trained to cope with a future pandemic of this scale. This study also highlighted that healthcare organisations need to be prepared and able to fully support staff by ensuring effective and clear lines of communication. Previous recommendations should be incorporated in a timely manner because they will benefit the day-to-day running of services and staff morale.

Although some participants adapted and were happy in their new role, despite the initial lack of training and redeployment anxiety, others decided to move home to be closer to family, transfer to other clinical areas, or left to look for a new job. This study identified that, at the time the survey was undertaken, 25% of redeployed nurses had resigned or were looking for a new job. At the time of writing, the figures had increased to 43% and, since merging with two other redeployed respiratory wards in the hospital, the total percentage of respiratory nurses who have left the respiratory directorate since March 2020 sits at 60%.

Further studies are required to explore how respiratory nurses in other hospitals coped with redeployment during the pandemic. Findings from any additional research would help further guide how to better support staff wellbeing, including identifying whether redeployment or the risks posed by COVID-19 itself had had the greater effect on staff wellbeing.

The UK is now 4 years on from the start of this pandemic; however, we are still living with the after-effects. Questions have now been asked about whether the country had been prepared sufficiently for an event of this magnitude, and steps are needed to better prepare the workforce for future pandemics that may occur. Essential action and adaptation are still required to support those nurses who remain in their roles following this pandemic to prevent a further exodus of skilled and experienced staff.

KEY POINTS

- It has been acknowledged that throughout previous pandemics healthcare workers experienced anxiety and distress, leading to a negative impact on their mental wellbeing

- This study survey examined the effects of rapid redeployment from one healthcare environment to a COVID-19 high-dependency unit/stepdown ward

- Nurses reported that redeployment was a stressful experience, leading to feelings of disempowerment, fear, insecurity, anger, depression and betrayal

- The results of this study show that both redeployment and COVID-19 had a negative impact on the mental wellbeing of the nurses surveyed

CPD reflective questions

- If you had been managing this situation, how would you have supported the nursing team as their manager?

- How could you support ward nursing staff in future?

- What lessons can be learnt to better prepare staff and healthcare services for future pandemics?