In February 2020, the first known case of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, causing the coronavirus (COVID-19) disease, was identified in the UK (Spiteri et al, 2020). In response, NHS trusts throughout the UK had to react, adapting their pathways of healthcare delivery to the patient. NHS England/NHS Improvement wrote to all acute trusts, asking for creation of COVID-19 ‘virtual wards’ (VW) as soon as practically possible (Powies et al, 2021). The request prompted questions around infrastructure, technology selection and information governance for trusts. Few wards were able to fully replicate the care of patients in physical inpatient beds. Perhaps the biggest challenge was how these wards would be staffed, particularly if they included full-time, round-the-clock and remote continuous monitoring.

Remote patient monitoring (RPM) uses telemetry to collect health data from patients outside the hospital setting and transmit it to healthcare providers in a different location (Noah et al, 2018). Typically cited advantages of RPM include early and real-time detection of illnesses, cost reduction, reduction in healthcare use, the ability to monitor patients continuously while permitting them to continue their usual daily activities and improved patient outcomes (Malasinghe et al, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic incentivised the adoption of this technology (Department of Health and Social Care, 2021). There was increased motivation to keep patients out of hospitals to prevent further spread of the disease and reduce risks for patients and staff, as well as a desire for early discharge to free up much-needed hospital beds (Gordon et al, 2020). RPM offered a solution that could help monitor patients for deterioration in their own homes and prompt intervention in those with evidence of deterioration.

Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust already supported the wider ‘digital hospital’ concept, with an active programme of work around wearable technology, based around the Current Health platform (Current Health Ltd, Edinburgh, UK). The COVID-19 VW was built on this platform and went on to accept patients from nine further clinical pathways. Three more remain in development. Uniquely, it was able to offer round-the-clock remote and continuous monitoring of patients. This article describes the service model and implementation of the VW, including nursing management considerations, to aid others in VW deployments.

Virtual ward service model

The vision of the VW was to provide safe and effective monitoring and a follow-up service for all patients, while facilitating early discharge, admission avoidance and physical bed occupancy reduction where possible and clinically safe. It existed as an alternative infrastructure for the hospital, with the potential for transferring patients as part of routine care, winter escalation or pandemic response.

The VW admitted its first patient on 8 February 2021 and operated 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, mirroring a physical inpatient ward. The distinction was made from the start that patients were transferred, rather than discharged, to the VW. Therefore, only patients who would have otherwise occupied a physical acute bed were transferred. Any patient who could be discharged home was discharged as normal. The VW was not designed to be part of the ‘step up’ or escalation pathways for primary care.

The VW had an operational lead (Band 8a) and VW manager (Band 7). Both were based on site to identify patients, respond to referrals and expand existing pathways. There were also six registered nurses (RN) (Band 5) from a variety of specialties, who provided round-the-clock care remotely (one RN per shift). The team were equipped with an iPhone (Apple Inc, Cupertino, US) with Current Health monitoring apps, a trust laptop and Alertive (Alertive Ltd, Ashbourne, UK) for internal communication. All patients on the VW were classed as inpatients, so the team had full access to the trust's clinical systems and services. The original team were all shielding at home, but there were no reported issues with connectivity. Subsequent hospital staff have worked from dedicated digital health offices.

Training was initially provided by Current Health and cascaded through the team, helping the staff become experts in remote healthcare delivery. There was a daily specialist consultant virtual ‘board round’ where management and discharge plans were reviewed. A general practice specialist trainee provided middle grade medical cover. A pharmacist-prescriber (Band 8a) supported the service with medication advice and oversight. The quality, safety, performance, finance and workforce of the VW was monitored through an established VW board. This was chaired/co-chaired by the chief clinical information officer (CCIO) and chief nursing information officer (CNIO) with escalations to the Digital Transformation Committee and/or Hospital Management Board (HMB) as appropriate. Once established, the only additional support required has been around reporting and business intelligence requests.

Patients were called daily (or more frequently if clinically required) by telephone or video call in ‘virtual visits’ that provided reassurance and the opportunity to discuss symptomology, wellbeing and progress. Typically, these would be carried out by the nurse overseeing the VW that day (Band 5). The patients were monitored using the Current Health platform. The platform consisted of a kit given to patients and a web dashboard for staff to view the patients' observations. The kit included a wearable armband providing continuous, clinical grade measures of oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, pulse, motion and skin temperature. The armband integrated with a tablet for video visits and as a means for patients to report symptoms. Depending on the patients' needs, integrated blood pressure cuffs, weighing scales or spirometers could be seamlessly added to the kit as required. The kit also included a ‘home hub’, which connected the wearable to the cloud via a home internet connection or a 3G network sim card for those without home internet. The sim card was supplied by Current Health as part of the kit, and had sufficient bandwidth to conduct optimised video calling. The wearable was worn at all times except when patients were washing. If the patient was away from home, vital signs were still collected and stored on the wearable for up to 8 hours. These were then automatically uploaded when the patient returned within range.

The web dashboard displayed the patients' observations in a format similar to the familiar hospital observation chart. Alarms were set, so that when patients' vital signs exceeded a preset threshold, alerts would be sent to the team via push notifications and also displayed on the web dashboard. Progress could also be tracked in the longer term via downloadable aggregated reports.

Implementation of the virtual ward

The implementation began with scoping, staffing and training. The staffing model was initially designed to implement a pathway for COVID-19, but in the knowledge it would quickly expand. To begin, staff who were shielding were recruited, as they could support the VW at pace and remotely. The initial costs were the remote working kit described above and a Band 8a operational lead. The operational lead was recruited as a secondment and based on site to support the service and identify, educate and transfer patients to the VW, initially from inpatient wards and later directly from the emergency department. Training of subsequent staff was supported by Current Health and the operational lead and administered remotely. The VW was introduced in two stages. First, suitable inpatients within the trust were transferred to the VW, then the VW facility was expanded to incorporate other appropriate patient pathways. Respiratory, oncology and palliative care pathways followed COVID-19 and, by May 2021, there were eight pathways (adding ‘Awaiting diagnostics’, ‘Awaiting treatment’, ‘COVID-19 in pregnancy’, and ‘Acute [‘hot’] gallbladder’), with subsequent pathways being added as word spread around the trust.

The VW staffing model was designed to support 20 virtual beds with the ability to flex. It subsequently expanded to 40 beds, with the addition of two Band 6 nurses based on site to identify and assess patients and be available to support virtual care. The initial deployment was paid for by COVID-19 emergency funds, followed by winter funding (while a business case was being completed) and, latterly, national funding via the integrated care system. Purchasing was via GCloud and a data protection impact assessment was completed.

Criteria for admission to the VW were patient consent, ability to communicate with the team and to operate the equipment themselves (or with support from their family/carer). During the consent process, patients were informed that removing the kit prematurely would equate to a self-discharge against medical advice. Once the VW was operational, patients transferred to the ward following one of the clinical pathways listed above. The kit was given to patients in the hospital once they were assessed as a suitable for transfer to the VW. Alternatively, it could be sent out via volunteer driver or taxi if, for example, the patient was admitted to the VW from a clinic.

Admission templates were designed for each pathway, outlining inclusion/exclusion criteria, alarm parameters, lead consultant, overall responsibilities and the escalation process should a patient deteriorate. Alarm parameters were first set on a cohort basis aiming for optimal sensitivity and specificity in the VW context, then subsequently adjusted on a per-patient basis as required. If a patient's vital signs became deranged, the team then followed the pre-defined ladder for escalation, typically to a nurse specialist, with the consultant on call or arranging transfer back to the hospital to a specialist ward (not to the emergency department unless clinically indicated).

Evaluation of the virtual ward's success

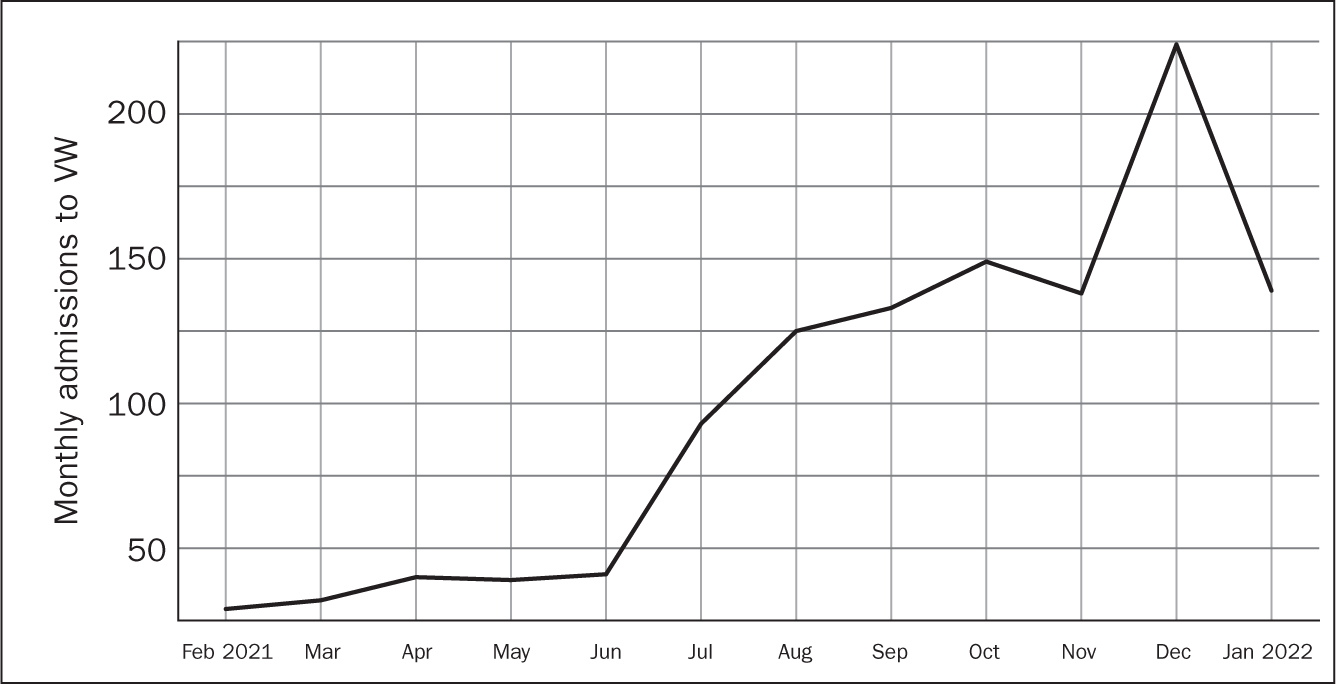

Some 852 patients were admitted to the VW in its first 12 months of operation (Figure 1). The median age was 44 years (IQR 31–69) and the length of monitoring with Current Health was 3.9 (2.4–6.7) days. By far the largest group of patients were those suffering from COVID-19 (Table 1). Patient feedback was captured by the VW assistant practitioner (Band 4) after the patient had been discharged from the VW. Patients were asked if they would be willing to answer eight open questions. Respondents gave answers over the phone, and these were recorded by the VW assistant practitioner and stored in a spreadsheet on a secured shared drive hosted by the trust. Some responses were recorded verbatim, while others were summarised, paraphrased and/or written in third person (for example, ‘It was very simple, as it had been explained so well’) by the VW assistant practitioner. Some 290 VW patients or caregivers of patients completed the questionnaire. The questions are listed in Box 1.

Table 1. Patients admitted to the Virtual Ward by specialty

| Clinical specialty | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiology | 31 | 3.6 |

| COVID-19 | 370 | 43.4 |

| COVID-19 (maternity) | 213 | 25.0 |

| Endocrinology | 22 | 2.6 |

| General medicine | 70 | 8.2 |

| General surgery | 74 | 8.7 |

| Oncology | 10 | 1.2 |

| Palliative care | 3 | 0.4 |

| Respiratory | 57 | 6.7 |

| Total parenteral nutrition | 2 | 0.2 |

Box 1.Patient feedback questions

- Do you feel you were given all the information you needed before being transferred onto the virtual ward?

- How easy do you feel the Current Health kit was to set up?

- How do you feel wearing the wearable device?

- Did you at any time have to contact Current Health/Virtual Ward Team for support with the wearables kit? Were they able to resolve your issue?

- Did being part of the virtual ward make you feel more confident in leaving Hospital?

- Is there anything we can do to improve?

- Would you use the service again, and would you recommend it to family and friends?

- Overall, how do you feel about the service you received from the NNUH Virtual Ward Team?

The authors loosely followed the steps for thematic analysis presented by Braun and Clarke though data were not transcribed as the calls were not recorded, as described above (Braun and Clarke, 2014). The collection of this feedback data was considered as service evaluation and was not submitted for NHS Research Ethics Committee review (Health Research Authority, 2022). The steps for the analysis included reading and familiarisation; coding; searching for themes; reviewing themes; and defining/naming themes. One reviewer (JLT) analysed these data and found the following major themes: confidence, early discharge from hospital and technical issues.

Confidence

Many participants mentioned that being part of the VW increased their confidence being at home:

‘[I was] worried about leaving hospital, so with VW I felt like I was still being looked after and knowing the nurse was there was a comfort.’

JB, male, 86 years old

A few patients still expressed some level of anxiety, including JS:

‘[The] wearable allowed patient to be discharged from hospital, which she wanted but made her anxious.’

JS, female, 74 years old, as reported by admin support

Early discharge

Many patients expressed great relief at being able to leave the hospital and return home earlier thanks to the VW. One patient said they:

‘felt depressed in hospital and over the moon when VW was suggested.’

while another VW patient commented that:

‘Being in hospital was bringing [me] down so going home early really helped.’

Technical issues

Despite the overwhelmingly positive feedback from patients who entered the VW, very occasional technical issues with the remote patient monitoring equipment were mentioned as a point of frustration. A handful of patients complained that: ‘

‘Video calling never work[ed]’ and ‘Readings [were] not being transmitted.’

These issues were fed back to Current Health and resolved.

Benefits and challenges

The VW was able to offer 24/7 remote, continuous monitoring to 852 patients in its first year. Overall, the feedback from these patients and their caregivers about the VW was extremely favourable, with 100% saying they would recommend the VW to family and friends, and two patients saying they had already told friends and family about it.

In addition to increasing hospital capacity at a time of great need, staff also highlighted the benefits of being able to work from home to the operational lead, even when having to isolate, or if they were unable to work in the hospital for physical or mental health reasons. Two nurses, reassigned to the VW at the start as they were shielding, chose to join the team permanently. The junior doctors who supported the VW were also shielding and valued the opportunity to continue to practise from home. Finally, the demand to cover staff who were off sick at short notice was greatly simplified, as the staff member covering them could log on from home.

The most significant challenges of the VW related to awareness of its presence, and differing perspectives on its role in the eyes of potential users. There were many versions of a virtual ward across the UK at that point, which engendered different expectations from users. The original definition was as a COVID-19 VW but, as the pandemic evolved and it expanded, it was renamed simply the VW to drive adoption from more specialties. Patients were encouraged to ask about the VW but there was a perception that the VW would create additional workloads, which made clinicians wary, given the singular challenges of the pandemic. This was overcome by demonstrating that the VW could provide holistic care (only escalating when strictly necessary) and, with robust planning, did not create additional workloads once implemented.

Conclusion

The implementation of the NNUH VW was challenging but highly beneficial in a time of exceptional pressure on staff and services. The VW was able to offer 24/7 remote, continuous monitoring to 852 patients in its first year of operation. It expanded from patients with COVID-19 to those with a wide variety of conditions, traditionally treated as physical inpatients. The VW has now expanded to 40 beds and is in the process of completing a business case to become substantive, while assessing opportunities to expand across Norfolk and Waveney. This continued provision aligns with the local and national trends towards the digitisation of healthcare.

Digital technology, remote patient monitoring and VWs are becoming part of the NHS. In the future, many nurses will work virtually at some point in their career. Understanding the challenges, lessons and opportunities will ensure that these deployments are efficient, safe and satisfying for patients, staff and their employers.