Population screening is an important public health initiative that saves thousands of lives each year. Screening services are often poorly understood by non-public health professionals and the public. In addition, because screening programmes help to protect us from developing health issues later down the line, they often do not receive the recognition they deserve for the harm that they prevent.

Rather than diagnosing disease, the screening process recognises the chance that an individual may develop the condition being screened for (Wilson and Jungner, 1968; UK National Screening Committee, 2015). First developed in the early 1960s, population screening initially focused on the eradication of communicable diseases (Wilson and Jungner, 1968).

However, improved availability and accessibility of treatments means that contemporary screening practice is now wider than communicable diseases and covers the 11 NHS population screening programmes, which include screening for a number of cancer conditions (Department of Health (DH), 2015). Screening therefore marks the beginning rather than the end of a person's healthcare journey and is a significant component of early intervention. It relies on people understanding screening, being able to access services and clear messaging from health and care professionals.

Contemporary national and international population screening programmes continue to save thousands of lives each year (DH, 2015). For example, the cervical screening programme prevents at least 5000 deaths a year. More than 1000 children each year can benefit from education as soon as they start primary school because of early intervention for hearing loss that may otherwise have gone undetected until much later in their life (DH, 2015).

The UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) advises ministers and the NHS in all four countries of the UK on all aspects of population screening and supports implementation. The UK NSC is an independent committee that provides evidence-based recommendations to ministers in each UK country and builds on the World Health Organization's ‘principles and practice of screening for diseases’, developed by Wilson and Jungner (1968).

Screening programmes are only recommended where the offer to screen provides more good than harm. Reviews are carried out against the UK NSC's internationally recognised criteria. These cover the:

- Condition being screened for

- Screening test

- Treatment for the condition

- Screening programme itself.

All NHS national screening programmes are then commissioned and delivered in the NHS with public health advice and support from Public Health England (PHE).

CASE STUDY

Aminah is 18 years old and has been in the UK for 4 weeks. As a refugee, she travelled alone from Somalia and had a baby within 2 weeks of arrival. She is living temporarily in a hostel, has one room and shares the kitchen and bathroom with 10 other families. She has no recourse to public funds, so the hostel staff have given her a mobile phone so she can receive text messages.

A midwife visited and completed the newborn blood spot screening when the baby was 5 days old. The midwife tried to alert you, Aminah's health visitor, to the need for an interpreter but the message did not get through in time for your new birth visit. This visit was essential because the newborn screening sample was insufficient and needed to be repeated. Consequently, you visited without an interpreter but were able to access help using the Language Line, an interpreting and translation service.

Having recently completed the All Our Health screening module as part of your continuing professional development (CPD), you knew that, to be successful, a screening programme depends greatly on the health professional's ability to explain the process to enable the client to make informed choices about engaging in the programme. Your use of the Language Line helped you to explain the reasons for repeating the screening. The interpreter also helped Aminah to explain that, owing to her inability to speak English and unfamiliarity with the area, she was frightened to leave the hostel and take her baby to the hospital for the repeat screening. You were then able to reassure Aminah that the test could take place at the hostel.

In response, you negotiated another home visit from the midwife and the interpreter to repeat the screening. The interpreter also agreed to text (in Somali) Aminah the day before the midwife's visit to remind her. With the help of the interpreter, you were also able to explain the purpose of the screening, that it is free and what will happen next.

Having completed the online population screening module, you know that time is of the essence and that the repeat screening must be processed as soon as possible to avoid any delay in starting any essential treatment.

You know that multi-agency working is easier if you can talk to other health professionals, but because you are new in post you have not worked with the interpreter or the midwife before. You are pleased that in less than 30 minutes you have arranged the repeat screening and, with the help of the midwife and interpreter, you have created continuity of care for Aminah. This will help Aminah engage with the screening programme and the health visiting service.

You also feel secure in the fact that Aminah's baby will benefit from a screening programme that can identify nine serious health conditions (PHE, 2019).

Health inequalities and screening

Despite the provision of a national screening programme, research shows that some people choose to access these services more than others. Although not new, the inverse care law persists in all areas of healthcare, including screening. This means that the people at higher risk of disease are least likely to access the service, despite it being freely available (Tudor Hart, 1971; Marmot, 2010). Indeed, factors including poor health knowledge and understanding mean that screening may be accessed more by some communities than others.

The design and delivery of the screening offer is constantly under review to make it easier for everyone to access, make informed choices and maximise the benefit to their health and wellbeing. These mechanisms include the use of text messaging to remind people about their appointments, social media campaigns to raise awareness and the provision of easy-to-read and accessible resources and video clips.

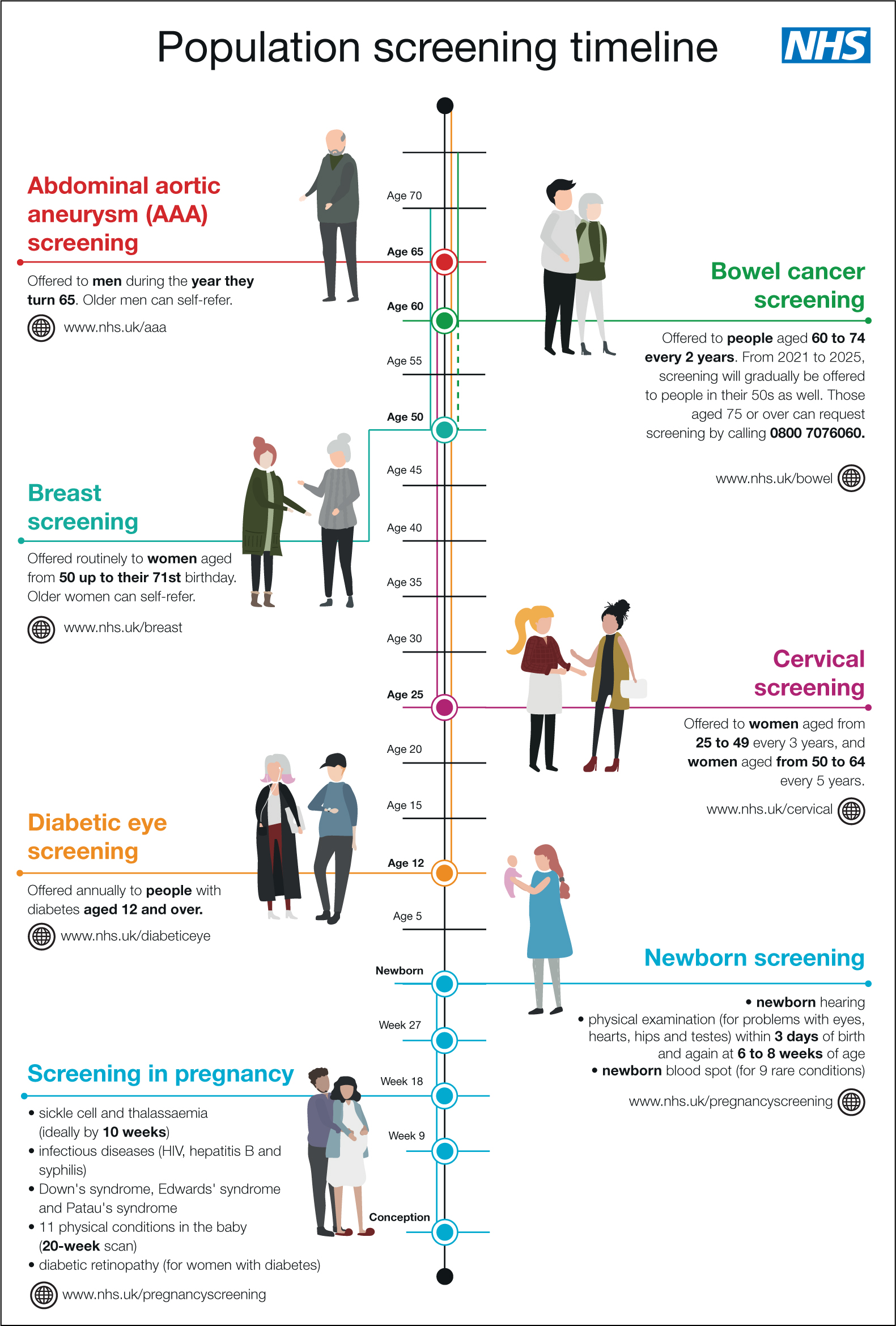

All health and care professionals must be familiar with evidence-based measures to improve access and accessibility of screening programmes to ensure individuals can engage with the offer of screening and make informed decisions. Detailed guidance and advice were published earlier this year by PHE to support providers and commissioners reduce screening inequalities (PHE, 2021a). A population screening timeline is one of the resources available from PHE (see Figure 1) (PHE, 2021b).

Figure 1. Population screening timeline

Figure 1. Population screening timeline

Enhancing your knowledge and practice

To support all health and care professionals to enhance their knowledge and, more importantly, to take greater action on key public health issues, PHE has published free online e-learning resources as part of a programme entitled ‘All Our Health’ (PHE, 2019). Already being accessed by thousands of health and care professionals, the population screening e-learning resource aims to support professionals by:

- Enhancing your understanding of specific activities and interventions that can support population screening

- Increasing your understanding of health inequalities related to screening and actions that can be taken to address this in your area

- Helping you think about the resources and services available in your area that can help people access local screening services

- Helping you find information about the key NHS screening programmes that will allow you to support people to make the right screening choices for them.

Building back better and fairer

As we start to focus on the recovery phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be essential for our nursing and midwifery workforce to appraise the lessons learnt and consider what changes need to be made to ensure that we genuinely build back better and fairer. This will require our profession to use the 2020s as a decade that sees transformation across our nursing and midwifery workforce, placing equal focus on both preventing disease and treating it.

Given the important role that screening plays in preventing or delaying ill health or premature death, we must prioritise this area of practice and take every opportunity to address equitable access and address unacceptable health inequalities. As nurses, we can act as a force for change in supporting healthy communities and challenging policy and practice for the greater good. As the largest and most trusted professional workforce, we have the potential to make change happen.