There are an estimated 600 clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) in stoma care in the UK (Hodges, 2022), working predominantly in England. The stoma care CNS provides care for people preparing for and living with a stoma pre-operatively, postoperatively and in the long term.

Pre-operative practice includes stoma siting, where the stoma care CNS will mark the place on the abdomen where the surgeon will form the stoma, and providing pre-operative counselling (Katté and White, 2021). Postoperative care includes preparing the person with a newly formed stoma for stoma self-care, identifying and managing complications and planning a safe discharge from hospital to the community (Swash, 2022a). In the long term, care may include assessing and managing complications, such as a prolapsed stoma or parastomal hernia (Skipper, 2021), evaluating care interventions and providing psychosexual and social support. At each stage of the care pathway, the stoma care CNS role is likely to involve advanced clinical reasoning and tailoring decision-making knowledge and skills to the individual needs of patients, many of whom are vulnerable (Swash et al, 2022b), such as people who have dementia and a stoma (Swash et al, 2022c).

Stoma care CNS roles and settings vary both within the UK and around the world. In other countries, the role can incorporate continence and wound care. In the UK, stoma care CNS roles vary, reflecting patient needs. Nurses might be employed by the hospital or a community organisation, depending on which organisation provides the service. In addition, professional boundaries are becoming blurred with the development of newer positions, including those held by specialist but unregistered practitioners. It is therefore uncertain what the essential and common areas of the stoma care CNS position are. The role of the stoma care CNS requires evaluation to determine clear boundaries and capture and clarify its complexities.

Background

Defining the stoma care CNS role is difficult because of the number and variety of activities that are undertaken and the rapid way in which nursing roles evolve.

In the wider context, the International Council of Nurses (ICN, 2020) define the role of the CNS in the context of possessing expert knowledge and decision-making skills. This emphasises the difference between being a novice and working at an advanced level. Further compounding the challenge of defining specialist practice is the growing emphasis on advanced practice, with roles such as the advanced nurse practitioner. The ICN (2020) explores the need for additional graduate education. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2021) describes the four pillars of advanced practice as clinical expertise, education, leadership and evidence. It is of note that the ICN (2020) and the RCN (2021) descriptions concur.

More than 10 years ago, the RCN (2009) described the role of the stoma care CNS but this has since evolved and the changes have not recently been explored. Ensuring the stoma care CNS role is understood, what it can involve (activities can vary, and the work can be linked with cancer care) and standards of care required for advanced nursing practice need to be maintained. Furthermore, demonstrating the value of the stoma care CNS is useful to inform service developments.

This review was also undertaken to inform a subsequent Delphi consensus undertaken at the UK national stoma conference.

The review

Aim

The aim of the scoping review was to synthesise the available evidence to answer the question formed using the PCC (population, concept, context) from the Joanna Briggs Institute's Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris and Munn, 2020). The intention was to establish ‘How is the role of the CNS in stoma care in the UK described and understood within the published evidence?’

Design

The original idea was to undertake a systematic review, but it became clear during preliminary searches that there was no published research on this topic. The review was therefore revised to be a systematically undertaken scoping review.

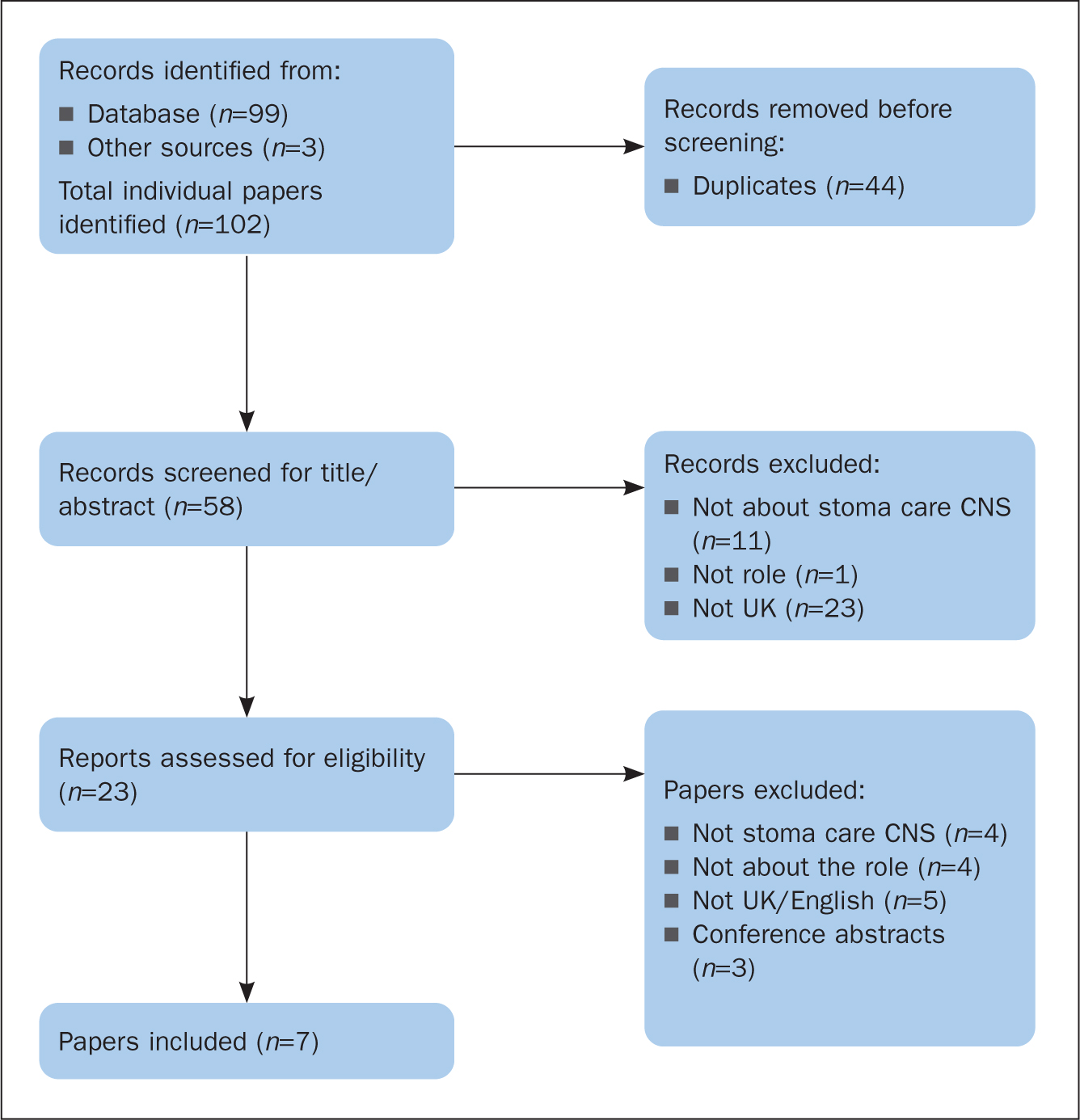

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) selection process (Figure 1) (Page et al, 2021) was used to inform the methodological approach employed to conduct the systematic scoping review. The process had three steps: identification of relevant literature; inclusion/exclusion; and review of the included papers.

Search methods

Three online databases – Embase, AMED and Ovid Medline – were considered relevant after preliminary searches to test the terms within these databases were carried out. These databases were systematically searched; the final search on 26 August 2022 used the search terms nurs* AND (stoma OR ostomy OR ostomate OR ostomist) AND (role OR duty OR duties OR obligation OR accountability OR performance OR representation OR job OR function OR position OR skill OR task OR work OR responsibility) within paper titles.

Eligibility criteria (Table 1) were used to screen papers, first by titles and abstracts of citations identified through the initial database search and then the full-text papers identified for potential inclusion. There were no restrictions on publication date, but it was not anticipated anything would be found before 1971 when the first UK stoma nurse was appointed (Black, 2000).

Table 1. Eligibility criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Description of the role of the clinical nurse specialist in stoma care in the UK | Nurses outside the UK | The study population is nurses working in the specialist field of stoma care within the UK |

| Papers written in EnglishFull papers, including reviews, commentaries and guidelines | Conference abstracts | Authors can only read EnglishPerspectives on the role of the clinical nurse specialist in stoma care are likely to be captured in the wider literature as no research was available |

Further papers for inclusion were identified through relevant professional guidelines and reference lists of papers that met the eligibility criteria. Two reviewers (JB and AB) independently screened the title and/or abstract then the full text of each paper identified for review. Differences were resolved by discussion; discussion with the third author (GT) to resolve disputes was unnecessary.

Search outcome

There were 99 articles identified in the initial search; three guidelines were added and 44 duplicates were removed. Thirty-five papers not meeting the eligibility criteria were rejected at the title and abstract screening stage. Twenty-three full-text papers were assessed for eligibility and seven (Table 2) were included for review.

Table 2. Papers included in the review

| Author (year) | Aim of paper | Design of paper | Meaning points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comb (2003) | To explore the role of stoma nurses in cancer care | Case study | 16 |

| Royal College of Nursing (2003) | To provide guidance on documentation in stoma/colorectal nursing | Narrative review | 4 |

| Skingley (2004) | To describe improvements achieved by educating non-specialist, community-based nurses | Narrative review | 29 |

| Royal College of Nursing (2009) | To improve documentation in stoma care nursing | Narrative review | 32 |

| McGrath (2017) | To explore the role of the specialist nurse in managing stoma-associated problems | Narrative review of study follow-up | 8 |

| Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK (2018) | To detail competencies for stoma nurses working at band 7 | Competency framework | 70 |

| Henbrey (2021) | To explore the role of stoma care CNS in maintaining quality of life in palliative care | Literature review | 25 |

Quality appraisal

No critical appraisal of the included papers was attempted as no research papers were identified. The authors recognised that it would be appropriate to: include a wider range of literature to answer the search question; and use the findings of the review to inform a consensus study through which the findings would be indirectly appraised.

Data analysis

The results from the review were synthesised using content analysis. Content analysis enables large amounts of text to be transformed into a highly organised and concise summary of key points (Erlingsson and Brysiewicz, 2017).

Data were broken down into meaning units; these are short pieces of text that maintain original meanings. During the analysis process, each reviewer listed the meaning units from each source. JB and AB reviewed all included papers independently to identify meaning units, which were then discussed and agreed. If a meaning unit was identified in the same source more than once, the second and subsequent occurrences were ignored. Results were added to a purpose-designed Excel spreadsheet by AB. Related meaning units, either through content or context, were grouped into subcategories (codes) and categories. These categories were then grouped into themes.

Discussion was held with all authors until agreement was reached over the meaning units, codes, categories and themes.

As the findings were to be used in a consensus study, statements were formed to capture each of the 13 categories identified to describe the role of the stoma care CNS.

Results

The seven included papers were published in the UK between 2003 and 2021 (Table 2). There were three guidelines (RCN, 2003; 2009; Association of Stoma Care Nurses UK (ASCN UK), 2018), two narrative reviews (Skingley, 2004; McGrath, 2017), a case study (Comb, 2003) and a literature review (Henbrey, 2021).

The results of the synthesis are summarised in Table 3. There were 184 individual meaning units and 30 codes derived from the seven papers. The codes were grouped into 13 categories. During data synthesis, it became clear that the 13 categories effectively fit into four themes. The themes reflected the four pillars of advanced practice: advanced clinical practice; leadership; facilitation of education and learning; and evidence, research and development (RCN, 2018).

Table 3. Relationships between themes, categories and meaning units

| Theme | Category | Code | Number of meaning units (n=184) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced clinical practice | Has specialist knowledge and skills | Specialist knowledge and skills | 27 |

| Support provider | Support | 21 | |

| Counsel | 11 | ||

| Delivers care | Provides care | 22 | |

| Assesses, plans, documents and evaluates care | Assessor | 13 | |

| Plans, documents and evaluates care | 4 | ||

| Skilled communicator with patients and their significant others | Collaborates and communicates with patients | 7 | |

| Facilitation of education and learning | Specialist point of contact for information and advice | Patient adviser | 13 |

| Be a resource | 5 | ||

| Provide patient information | 5 | ||

| Mentor/preceptor | 1 | ||

| Educator | Educate patients | 3 | |

| Educate healthcare professionals | 3 | ||

| Educate others | 2 | ||

| Educate significant others | 1 | ||

| Educator | 2 | ||

| Leadership | Autonomous and collaborative | Collaborate/communicate with multidisciplinary team and other health professionals | 7 |

| Signpost | 2 | ||

| Autonomous | 2 | ||

| Refer | 1 | ||

| Advocate and role model | Patient advocate | 3 | |

| Speciality advocate | 2 | ||

| Service improver | 4 | ||

| Role model | 1 | ||

| Steward of the NHS | Resource/product management | 5 | |

| Manager | Manager | 3 | |

| Leader | Leader | 1 | |

| Evidence, research and development | Uses and contributes to a specialist evidence base | Research | 6 |

| Uses evidence base | 4 | ||

| Audit | 3 |

Distribution of the categories, codes and meaning units varied between the four themes. Advanced clinical practice contained the most meaning units; leadership contained the most codes; and evidence, research and development contained the fewest categories, codes and meaning units. Advanced clinical practice contained five categories, seven codes and 105 meaning units. Facilitation of education and learning contained two categories, nine codes and 35 meaning units. Leadership contained five categories, 11 codes and 31 meaning units. Evidence, research and development contained one category, three codes and 13 meaning units.

Each of the 13 categories contained between one and five of the 30 codes; the median was two. There was an average of 14 meaning units per category. Four of the categories contained 20 or more meaning points, predominantly in the theme of advanced clinical practice. These categories were: is a support provider (n=32); has specialist knowledge and skills (n=27); is a specialist point of contact for information and advice (n=24); and delivers care (n=22). Five categories contained only one meaning unit: mentor/preceptor; educate significant others; refer; role model; and leader. Discussions to try to join meaning units revealed that topics such as manager and leader were distinctly different and should remain separate.

Of the 30 codes, three contained over 20 individual meaning units: specialist knowledge and skills (n=27); provides care (n=22); and provides support (n=21). These three meaning units were all in the theme of advanced clinical practice.

Discussion

This is the first scoping review to examine how the role of the stoma care CNS in the UK is described and understood within the published evidence base. The categories and themes identified reflect the diversity and complexity of the role within the context of advanced specialist practice.

The CNS can be described as a registered nurse who is authorised to practise as a specialist and who has advanced expertise in a branch of nursing that includes clinical, teaching, administration, research and consultant roles (Lowe and Plummer, 2019). The role of the stoma care CNS was first described in the UK in the 1970s (Black, 2000). Initially, the CNS role was developed to meet the changing needs of patients and in line with the evolving healthcare workforce. Subsequently, this nursing role developed to enable nurses to extend their clinical knowledge, expertise and skills to inform high-level, autonomous clinical reasoning and decision-making to improve care for patients with complex diseases or conditions (Chan and Cartwright, 2014). Similarly, in colorectal cancer, the role of the advanced nurse practitioner is described as including autonomous working (Carvalho et al, 2022), showing commonality between the different nursing roles.

Although associated with a high level of clinical expertise, the CNS role has long been considered to extend beyond specialist clinical practice. There are role expectations that include quality improvement, service and system management as well as staff education and leadership, including mentorship. These roles seamlessly combine to impact positively on the experiences and clinical outcomes of patients and their families (Kidner, 2022).

It is important to consider the transition from novice to advanced specialist practitioner. When a nurse first specialises in stoma care, they will have a degree of knowledge about the topic. However, it could be argued that nurses should not use the term CNS without first acquiring formal, specialist education. Health Education England (2017) states that health professionals working at an advanced level are required to work at master's level and are able to make sound judgements in complex, ambiguous situations.

This scoping review suggests that the stoma care CNS role largely conforms to the RCN's (2018) four pillars of advanced practice. Nonetheless, the extent to which each individual stoma care CNS meets these expectations will be determined by their personal expertise, experience, specialist education and scope of practice.

Advanced clinical practice

The largest reported interactions of the stoma care CNS related to the care and management of people living with a stoma. This included supporting preparation for stoma-forming surgery or working with significant others to optimise quality of life for people with a stoma; this was demonstrated by the prominence of advanced clinical practice within meaning units and categories.

These results, however, may have been influenced by the nature of the publications. Henbrey (2021) for example, focused only on the stoma care CNS role in palliative care. Palliative care is only a small part of most stoma care CNS roles, as many people live a long life with their stoma. Additionally, Comb (2003) included a large focus on building a rapport with patients to better enable the nursing process when issues arise. Rapport enables the patient to volunteer information to the stoma care CNS to enable assessment and resolution of issues.

Within clinical practice, it is important to identify and define the scope of practice of the stoma care CNS in both direct and indirect care (ICN, 2020). In the UK, doctors have a limited role in stoma care following surgery, with responsibility for this falling predominantly to the stoma care CNS. It is therefore unsurprising that the content analysis exercise identified the highest number of meaning units relevant to the possession of specialist skills and knowledge category. This involves managing complex situations such as choosing the most appropriate place for the stoma to be surgically formed, as well as managing stoma complications that require complex decision-making skills such as the management of enterocutaneous fistulae.

Excellent communication skills are fundamental to the provision of support and counselling as well as when conducting the essential roles required by the nursing process of assessing, planning, implementing and evaluating stoma care needs. Support is essential to enable adjustment to life with a stoma, which involves profound disruption in the sense of the patient's embodied self. Counselling is necessary to enable relationships with others to enable the person living with a stoma to experience people and engage with the world around them (Thorpe et al, 2016). The stoma care CNS needs a vast amount of knowledge and understanding to enable this, using sensitive and appropriate communication skills.

Facilitation of education and learning

The stoma care CNS facilitates learning within the clinical environment with patients and their significant others as well as with colleagues, in addition to their own education. The stoma care CNS is also a valuable resource, being the specialist point of contact for information and advice on stoma care for patients, significant others, colleagues and others. This aspect of the role is recognised by Kidner (2022), who describes the CNS role as a consultant to other health professionals to enable high-quality care. The ICN (2020) also identifies the part that the CNS plays in the provision of education to colleagues.

Self-education is also an important aspect of the stoma care CNS role. Historically, the English National Board for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting enabled training to be conducted to a set standard within all institutions in the UK that provided education in stoma care, with education available at diploma and degree level. Once the board was disbanded in the 1990s (Stronge and Burch, 2019), specialist education was offered at the same levels but the range of content varied considerably between institutions. With nursing becoming a graduate profession, a greater importance was placed on senior nurses such as stoma care CNSs having stoma-related qualifications at master's level. The RCN (2018) suggests that nurses working at an advanced level should be educated to master's level. The ICN (2020) concurs, stating a CNS has completed a master's degree specific to their practice.

However, there is no master's pathway for stoma care CNSs to complete in the UK, only a stoma-related module that is incorporated into a master's programme. It is uncertain how many stoma care CNSs have completed a relevant master's degree. Stronge and Burch (2019), in an audit, reported that 72% of stoma care CNSs had a stoma-specific qualification at degree level or above. This is an increase on an earlier audit, which reported that 49% of stoma care CNSs had completed a degree-level stoma-related module (Burch, 2014). The earlier survey of stoma care CNSs showed that 25% held a degree and 30% a master's as their highest qualifications (Burch, 2014). It is likely that these figures will have altered in the years since this audit was undertaken.

Stoma-related education was undertaken for three main reasons: professional development; to underpin clinical knowledge; and to improve patient care (Stronge and Burch, 2019). Therefore, CNSs in stoma care recognise the importance of improving patient care as well as developing themselves professionally through education.

Leadership

Leadership in the stoma care CNS role includes being a steward of the NHS, particularly regarding the management of resources and stoma products. Careful and efficient use of stoma products was described as important in the audit by Bowles et al (2022). One perception of nurses is that patients consider that stoma-related products being available on prescription means they can ‘have whatever they want’ (Bowles et al, 2022: S17).

In this review, limited meaning units were related to being a manager or a leader, indicating that these aspects of the role were not explicitly recognised in some of the publications reviewed. ASCN UK (2021) identified a set of quality statements to set standards and ensure stoma care healthcare goals are met. These standards do not include leadership or management, except in the foreword. Conversely, domain two of the ASCN UK band 7 stoma care CNS competency framework relates to leadership and management and includes overseeing the stoma service and being accountable for maintaining service standards (ASCN UK, 2018). It is possible that the role of management is associated only with the department lead. It could be that, because leadership was associated with management, it was not recognised and identified separately.

There was no discussion about sponsorship of nursing posts. A recent audit by Bowles et al (2022) showed that, in England, three-quarters of a large sample of stoma care CNSs (n=108) were directly or indirectly funded by industry.

The ASCN UK (2018) recognises leadership and management in their competency framework for stoma care CNSs but this is not included in the other publications. This may reflect the topics of discussion of publications or possibly suggests these aspects of the role have a lower priority than others, for the stoma care CNS.

Evidence, research and development

The CNS role needs to include the assessment of relevant data and research (Kidner, 2022) so practitioners are able to understand and draw up guidelines.

To enable service evaluation, the ASCN UK (2021) has undertaken work to improve the understanding of the care that should be provided and has also established a set of standards that stoma care CNSs can use to benchmark their care. As part of service improvement, Metcalf (2017) and Walker et al (2018), in their separate audits using the ASCN UK standards and audit tool, both recognised areas of their service that needed improvement. The number of research studies, audits and evidence-based articles about stoma care that are written by or include the stoma care CNS are increasing; this is improving the evidence to guide care and ensure that high standards are met and maintained.

The ICN (2020) considers the role of the CNS to include innovation and facilitating change. Change management and service development as well as undertaking research are not well described in the literature in relation to the role of the stoma care CNS. Evidence-based nursing is essential for all nursing roles, which is evident in the ASCN UK (2018; 2021) guidelines that have been published to assist the stoma care CNS.

Implications for practice

The blurring of nursing roles in the UK as they have progressed and evolved has resulted in disparity and confusion about them. It was considered necessary to define the stoma care CNS role, but there is no research on this topic, making role definition difficult. Further empirical enquiry is required.

There was some resonance between job roles within the reviewed papers. However, most papers were not written with defining the complete role of the stoma care CNS as an outcome but focused on select aspects of the role. This limited perspective may have contributed to a fragmented understanding of the role.

Anecdotally, fragmentation of the role may be perceived by colleagues and patients. For example, colleagues might see only aspects of the stoma care CNS role being undertaken, such as those that take place on the ward or in clinic. This can result in an incorrect perception of what is included in the role, excluding care provided within the community or management roles undertaken in the office. This limited perspective, with the stoma care CNS role being viewed through only one lens, does not enable a full understanding of the position.

A broader, more holistic role description and understanding are needed to include all aspects of the stoma care CNS role, with a comprehensive definition of the role through further research.

Clinical impact

This is the first scoping review undertaken to examine the stoma care CNS role. Although only UK roles were included, the findings might be transferable both to other countries and the various roles in the UK.

Consideration needs to be given to the need to move from specialist into advanced practitioner roles. This requires gaining advanced skills to enable transition into advanced roles through shadowing, networking and formal teaching (Gee et al, 2018). It could be suggested that the stoma care CNS should have a master's degree and additionally be expanding their scope of practice towards becoming an advanced practitioner with an increased focus on education, research and leadership, to match their clinical skills. There are master's programmes available that include specialist clinical modules such as stoma care as well as core modules that include clinical assessment, leadership, education, prescribing and research. Obtaining such an education would create a fully rounded advanced practitioner.

Results from this scoping review were subsequently used to inform a consensus study. A modified Delphi consensus was undertaken at the ASCN UK conference in October 2022 with a vote on the results of this review to see if they reflected the opinions of stoma care CNSs in the UK. Nonetheless, more research is needed to examine the CNS role in stoma care.

Limitations

A lack of studies on this topic meant that a systematic review was not possible; a scoping review was undertaken instead. None of these papers lent themselves to critical appraisal or would have been deemed robust evidence on a hierarchy of evidence; nonetheless, they were included within the review.

Papers were included because of the rationale for undertaking the scoping review: to establish how the role of the stoma care CNS is described and understood within the published evidence to provide baseline criteria for a modified Delphi consensus study. No research has been undertaken in this area, which shows a need for robust evidence; this would potentially be useful for UK workforce planning.

Limitations of this scoping review include missing potentially important publications because of the search terms used. However, the search terms were deemed to be appropriate to establish how the role of the stoma care CNS in the UK is described and understood within the published literature. Non-UK publications were excluded, there are disparities between roles and expectations in other countries, such as the additional roles around wound and continence care as well as care provided outside of the context of the NHS. Furthermore, the authors all have many years of experience in stoma care and education; they carefully considered the terms and no known articles were excluded.

To reduce bias associated with poorly conducted reviews, this review of the papers was robustly undertaken to ensure results were reliable. This was achieved by discussion and documentation of methods before undertaking the review.

Additionally, bias can occur during data analysis. Content analysis is useful for interpreting the meaning of the data but there is a risk that themes will be based upon the frequency of occurrence rather than their importance. This was avoided by discussion during the analysis process to ensure that the meaning of the sources was not lost. It was considered that the subsequent consensus study would enable the importance of each theme to be captured.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified a range of non-research papers to answer the question: ‘How is the role of the CNS in stoma care in the UK described and understood within the published evidence?’ It was identified that the stoma care CNS role is complex and involves all four pillars of advanced practice: clinical; education; management and leadership; and research.

The greatest proportion of the stoma care CNS role appears to be clinical practice, reflecting its patient-centredness, with education of themselves and others also highlighted as important. The management and leadership components of the role were identified but less well defined. The least prominent pillar of practice in the stoma care CNS role was research and evidence-based practice.

The review findings highlight that the stoma care CNS can be a novice or experienced specialist nurse. Consequently, the clinical pillar is likely to be most prominent in nurses with less experience and expertise, with the other pillars developing over time as expertise is gained and with continuing professional development. Confirmation of these role descriptors is required by the stoma care CNS through qualitative enquiry to ensure they are current and relevant.

KEY POINTS

- The clinical nurse specialist (CNS) in stoma care role is highly skilled and complex but not well understood

- The stoma care CNS role involves all four pillars of advanced practice: clinical; education; management and leadership; and research

- In publications, the stoma care CNS role is most commonly described around clinical care, reflecting patient centredness

- Nurses working at an advanced level should be educated to master's level

CPD reflective questions

- Reflecting on your role, does it meet the four pillars of advanced practice?

- How can you develop yourself and your role to better meet all four pillars of advanced practice?

- Reflecting on nursing in general, why are different roles important to meet the varying patient needs encountered?