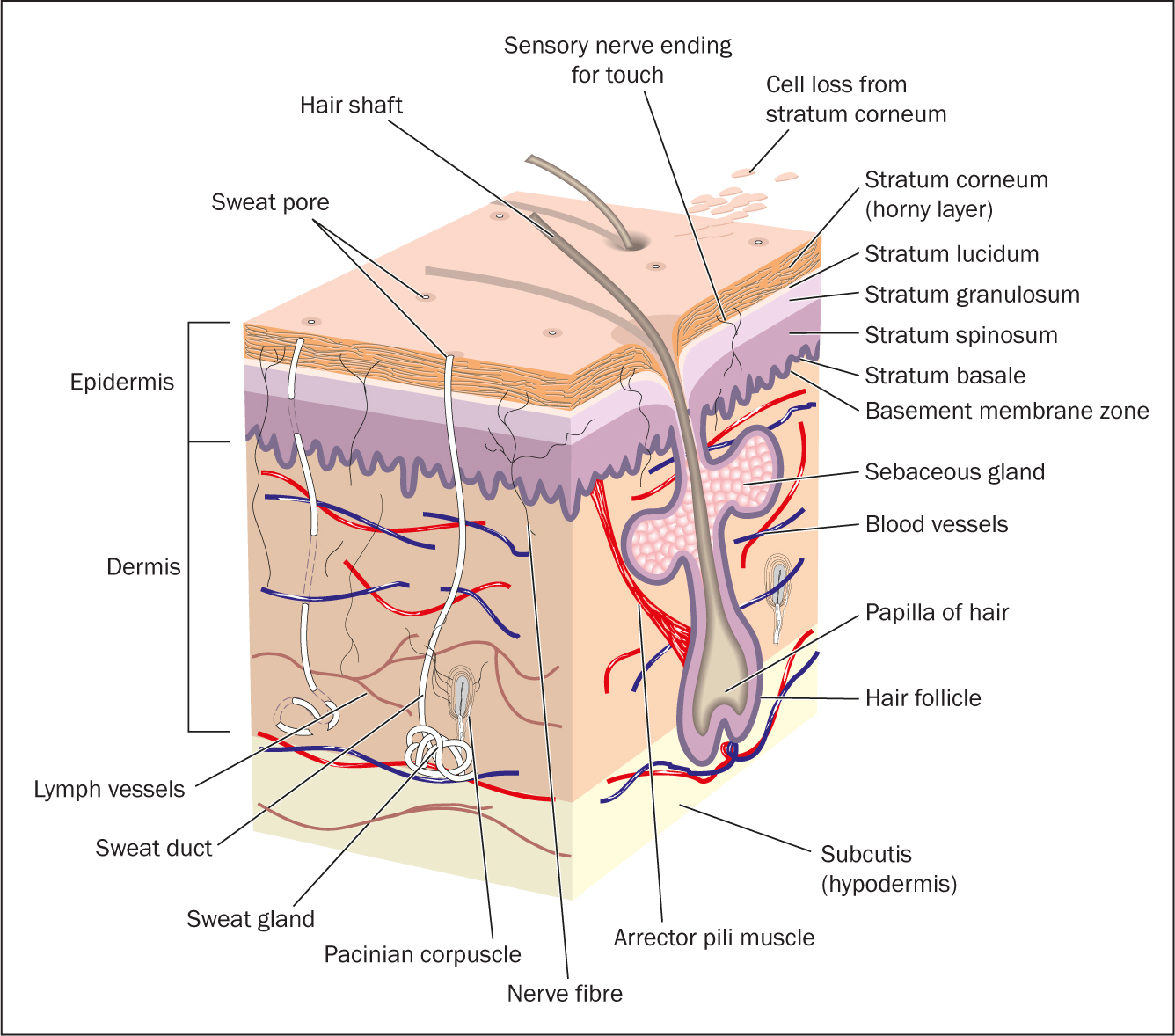

The skin is the largest organ in the body, accounting for 15% of all bodyweight. It is integral to both physical and psychosocial health and can have an impact on patients' quality of life (Wounds UK, 2018). In a healthy individual, the skin is strong, resilient and has a remarkable capacity for repair. It consists of three layers (Figure 1). The epidermis, the outermost layer, provides a waterproof barrier, the dermis lies beneath the epidermis, has a rich blood supply and contains tough connective tissue, hair follicles, sweat glands and sensory nerve endings; the hypodermis (deep subcutaneous tissue) is made of fat and connective tissue.

The skin has many functions, including:

- Protection: intact skin acts as a protective barrier and prevents internal tissues from trauma, ultraviolet light, toxins, pathogens and allergens, and changes in environmental temperature

- Barrier to infection: part of this is the physical barrier, but also the presence of sebum, a natural antibiotic chemical in the epidermis, and a surface acidic environment

- Sensory perception: nerve endings in the skin respond to painful stimuli, temperature, vibrations, touch and itch

- Temperature regulation: the rich blood supply in the skin can act as a ‘heat dump’ to enable body cooling. The subcutaneous fat acts as a heat source and heat insulation (Timmons, 2006).

- Production of vitamin D and melanin: vitamin D is important for bone development and melanin is responsible for colouring the skin, and protection from sunlight and radiation damage

- Communication: the skin is a sensory organ that enables communication through touch and physical appearance.

It also provides a good window into patients' health and wellbeing (Moncrieff et al, 2013).

Damage can occur if the skin becomes vulnerable to external and internal injury due to ageing and altered physiology (Moncrieff et al, 2013). Changes to the skin can be extrinsic, for example pressure, shear or friction, or there may be environmental damage. The latter could be caused by regular detergent use or sun exposure. Intrinsic factors can also have an effect on the skin, for example psoriasis, atopic eczema or an underlying illness. The ageing process has a significant effect on the skin: it becomes thinner, losses elasticity and moisturising factors, the blood supply is reduced and there is a decrease in the amount of fat under the skin (Moncrieff, 2013). This can result in the skin becoming fragile, vulnerable and dry (Kottner et al, 2013).

Gender also has an effect on skin integrity and sex hormones can inhibit skin repair. Research in mice has suggested that females repair faster than males due to oestrogen and lack of testosterone (Pyter et al, 2012). However, in females the menopausal transition involves a time of hormonal instability that affects the skin. These changes lead to decreased collagen content, water content, elasticity and thickness, which impacts on the quality of all the skin layers (Reus et al, 2020).

Other increased risk factors for compromised skin integrity include:

- Long-term conditions

- Critical illness

- Paralysis

- Obesity

- Cancer.

Several skin conditions affect skin integrity (Table 1).

Table 1. Skin conditions that affect skin integrity

| Rash | This could be a simple irritation, reaction, or medical condition |

| Dermatitis/eczema | An inflammation of the skin that can cause an itchy rash |

| Psoriasis | A genetic condition that causes sliver, scaly plaques on the skin |

| Pruritus | Often associated with dry skin |

| Cellulitis | An infection of the subcutaneous and dermis tissues |

| Malignant melanoma/basal cell carcinoma/squamous cell carcinoma | Skin cancers |

| Lipodermatosclerosis | Painful, tight, hardened subcutaneous tissue |

Source: Wounds UK, 2018

Assessment

Early recognition of people who are at risk of developing skin breakdown is an essential part of prevention. Assessment of the skin should be part of a holistic approach and carried out regularly in practice. When undertaking an assessment:

- Ensure good hand hygiene and that appropriate personal protective equipment is worn

- Explain to the patient how the skin assessment will be carried out and the reason for doing it. Gain consent

- Ask the patient for a full medical history, including long-term conditions and medications. Has the patient's skin changed recently? Has their health deteriorated?

Skin hygiene

- Ask the patient about their normal skin hygiene. Skin hygiene is essential for maintaining healthy skin and personal wellbeing. If the person is elderly and has dry skin, it is important to ensure that a balance between cleanliness and overwashing is maintained.

- Ask the patient which washing products they are using. There is a lack of evidence base on bathing practices, which means it is often guided by rituals and ‘tried and tested methods’ (Voegeli, 2008). Many detergents are alkaline and can alter bacteria flora on the skin. This increases the likelihood of pathogenic organisms' colonisation. An increase in skin pH can damage the skin barrier and cause irritation. Healthy skin can take up to 48 hours to recover following a change in pH. Younger or older skin and skin with inflammatory conditions such as eczema can take longer (Moncrieff et al, 2013).

Soap removes lipids from the surface of the skin, which can result in dryness. It is recommended that the use of emollients and soap substitutes will help promote skin health, reduce dryness and improve symptoms of itching and tightness. The use of emollients applied twice daily are also a key part in the prevention of skin tears and superficial pressure ulcers (Bale et al, 2004).

Risk factors

Identify if the patient has any risk factors for vulnerable skin. Complete a full head-to-toe skin examination paying particular attention to any areas of redness, discolouration, dryness, tenderness, irritation, or rash.

Pressure ulcers

- A patient's pressure ulcer risk status should be assessed using a validated pressure-ulcer risk assessment tool, such as the Braden scale (Bergstrom et al, 1987) or the Waterlow scale (Waterlow, 2005). All patients admitted to a healthcare setting, hospital or nursing home should have an appropriate pressure ulcer risk assessment performed within 6 hours of admission to the acute setting (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014)

- The patient should be reassessed if there is any change in clinical conditions or deterioration, following a surgical procedure or a change in mobility. Females are at greater risk of pressure ulcer development due to the distribution of body fat (Arnaoutakis et al, 2017)

- Use finger palpation to determine whether erythema or discolouration is blanchable. Initiate pressure ulcer prevention strategies in adults who have non-blanching erythema and repeat skin assessment hourly (Mitchell, 2018)

- Assess skin integrity and pressure areas. Note any changes of colour or discolouration. Are there any variations in firmness or moisture? Is the patient incontinent? Is there any moisture-associated skin damage (MASD)? Make sure that you include the correct classification for MASD (Mitchell and Hill, 2020) (Table 2)

- The SSKIN Care Bundle is commonly used in the NHS as a structured inspection protocol for checking skin and identifying risk of pressure damage. The SSKIN acronym spells out fundamental stages of skin inspection (Box 1).

Table 2. Types of moisture-associated skin damage

| Periwound moisture-associated dermatitis | Exposure to exudate from the wound in the inflammatory stage |

| Peristomal moisture-associated dermatitis | Exposure to urine, stool, sweat, wound drainage |

| Incontinence-associated dermatitis | Predominantly a chemical irritation resulting from leakage of urine or stool |

| Intertriginous dermatitis | Caused by sweat being trapped in the skin folds with minimum air circulation |

Source: Mitchell and Hill, 2020

Box 1.SSKIN acronym

| S | Surface |

| S | Skin inspection |

| K | Keep moving |

| I | Incontinence/moisture |

| N | Nutrition/hydration |

Wounds

- Check if the patient has a wound and the history of the wound. It may be necessary to complete a full wound assessment (Mitchell, 2020).

Skin conditions and injury

- Check if there is a skin condition present. This could be a rash, dryness, sore or itchy skin. Ask the patient to describe how it feels. How is it affecting their activities of daily living? Ask the patient how long they have had the skin condition? How often does it occur? Are there any triggers? Are there seasonal variations? Is there a family history of skin conditions? Do the patients' occupation/hobbies affect their skin condition for example repeated handwashing/use of hand sanitiser, exposure to chemicals/environmental factors? (Wounds UK, 2018)

- Does the patient take any medications or use any topical preparations to manage the skin condition? Have any past treatments been effective?

- Does the patient have any known or suspected allergies?

- Ask the patient if there are any treatments, actions or behaviours that influence the condition? Is there an odour present? (This could be an indication of the presence of bacteria.) For menopausal women a discussion around hormone replacement treatments, which have been shown to increase collagen content, dermal thickness, elasticity and hydration (Brincat et al, 2005), maybe appropriate

- Touch the patient's skin. Apply gentle pressure to feel the texture and temperature of the skin. A raised temperature may indicate an infection. Ideally, skin texture should be soft and smooth with an even texture. Document any areas where the skin feels coarse or irregular. The use of a body map would be beneficial

- Assess the patient for any signs of medical adhesive-related skin injury (MARSI), which can occur when a dressing is removed. The attachment between the skin and the adhesive is stronger than individual skin cells: this causes the epidermal layers to separate or detach from the dermis, resulting in mechanical trauma (Fumarola et al, 2020). Table 3 identifies the three main categories of MARSI.

Table 3. Categories of MARSI

| Mechanical | Skin stripping, blistering, skin tears |

| Dermatitis | Irritation in response to adhesive |

| Other | Maceration and folliculitis |

Nutrition

- Assess the patient's nutritional status. Good nutrition is the main strategy for maintaining good skin integrity and health (Kottner et al, 2013). A nutritional assessment should be used, for example the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) (Elia, 2003)

- Have a discussion with the patient about the type of meals they eat. Suggest supplementing diet with additional proteins, fatty acids and vitamins.

Protein is essential to skin health to allow optimal keratin production (an important protein in the epidermis). The function of keratin is to stick cells together and form a protective layer on the outside of the skin. If there is a protein deficiency and therefore a decreased amount of keratin the risk of skin breakdown is increased. Fatty acids help to lubricate and moisturise the skin and other essential vitamins such as C and A play an important role in tissue strengthening and regeneration (NHS Quality Improvement Scotland, 2010).

Skin tears

Risk factors for skin tears include: extremes of age, dry/friable skin, previous skin tear, a history of falls, impaired mobility, mechanical trauma and dependence on assistance for activities of daily living. General health, comorbidities, polypharmacy, malnutrition and impaired or changes in cognition are also all risk factors.

- Assess the patient's risk for skin tears—elderly patients are at higher risk. During the ageing process the skin becomes thinner, losing elasticity and moisture. Elderly patients can develop skin folds and wrinkles and lose the subcutaneous fat layer, making the skin more prone to tearing and bruising (Wounds UK, 2018)

- Discuss with the patient and relatives ways to mitigate risks of skin tears, as set out in Box 2. Skin tears can be extremely painful, affect the patient's quality of life and may increase the likelihood of hospitalisation.

Box 2.Reducing the risk of skin tearsAdvise the patient to:

- Keep fingernails trimmed short and avoid wearing sharp jewellery

- Consider protective padding or removing hazardous furniture to reduce risk of falls

- Cover skin with appropriate clothing, shin guards, stockings or retention bandages

- Use emollients and other skin-friendly products

- Avoid friction and shearing

The nurse should:

- Use good manual-handling techniques

Source: Wounds UK, 2018

Skin care plan

- Discuss with the patient an individualised skin care plan. This would include using a skin-friendly cleanser (not traditional soap), warm water (not hot) and promoting good general skin health

- Ask the patient about their perception of their skin status. Identify the patient's goals and priorities in maintaining healthy skin. Agree a treatment plan and identify regular review dates.

Virtual assessments

Where possible, it is recommended that full skin assessments should be carried out face-to-face with the patient. However, the current COVID-19 pandemic has impacted on patient consultations and moved many of these online. For online skin assessments, nurses must ensure the following:

Preparation

- Prepare the patient for the virtual consultation. Explain what will happen and how this will take place. Ask the patient to have all previous skin treatments with them, any prescription items and anything else they use on their skin

- Ask the patient to take pictures of the skin condition prior to the consultation, particularly if these are in hard-to-see areas. They may need a family member's support with this. Ask the patient to make sure that there is good lighting (free from shadows) and, ideally, that the size of any image file is less than 1MB for sending.

The consultation

- Confirm whom you are speaking to and if there is anyone else in the room with the patient. Start by asking the patient for verbal consent to undertake the virtual assessment

- Take a full medical history. You may be able to view the skin condition online or from the images sent. Ask the patient to describe the condition, ie how does it look and feel? Are there any noticeable changes in colour or texture in particular areas? Does it appear anywhere else? The more descriptive information you can get from the patient the better

- Review the pictures and discuss self-care with the patient. Arrange for a follow-up consultation within 2 weeks, depending on diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusion

Good skin health is essential for personal health and wellbeing. The skin is often a ‘window’ to a patient's overall health condition and should be assessed regularly as part of a holistic assessment. Early recognition of skin changes and interventions can have a significant impact on a patient's quality of life and will reduce the risk of pressure damage and skin tears.

KEY POINTS

- Skin assessment is essential for holistic care

- Damage to the skin can occur if it becomes vulnerable to internal and external injury

- Early recognition of risk factors is an essential part of prevention

CPD reflective questions

- In your practice, how often do you carry out a full skin assessment with patients?

- How often do you discuss skin hygiene with patients and their families?

- Can you think of anything you can do to improve this area of practice?