Approximately 268 000 people in the UK are living with bowel cancer and more than 42 000 people are diagnosed with bowel cancer every year (Bowel Cancer UK, 2019). The NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England/NHS Improvement, 2019) states an ambition that by 2028, a further 55 000 patients a year will survive longer than 5 years after diagnosis. Due to this growth, there is an increased focus on post-treatment cancer survivorship issues. With 31.5% of bowel cancers occurring in the rectum (Cancer Research UK, 2021), many cancer survivors struggle with the consequences of cancer treatment. An example of this is low anterior resection syndrome.

Low anterior resection syndrome

Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) is a collection of symptoms that may result from a low anterior resection for bowel cancer. Keane et al (2020), in their international consensus definition of LARS, identified eight symptoms and eight consequences that can result from low anterior resection surgery. They suggested that a diagnosis of LARS can be made when a patient suffers from at least one symptom, leading to at least one consequence (Table 1).

Table 1. Identifying low anterior resection syndrome

| LARS is diagnosed when a patient has at least one of these symptoms following surgery, leading to at least one of the consequences/areas affected | |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | Consequences/areas affected |

|

|

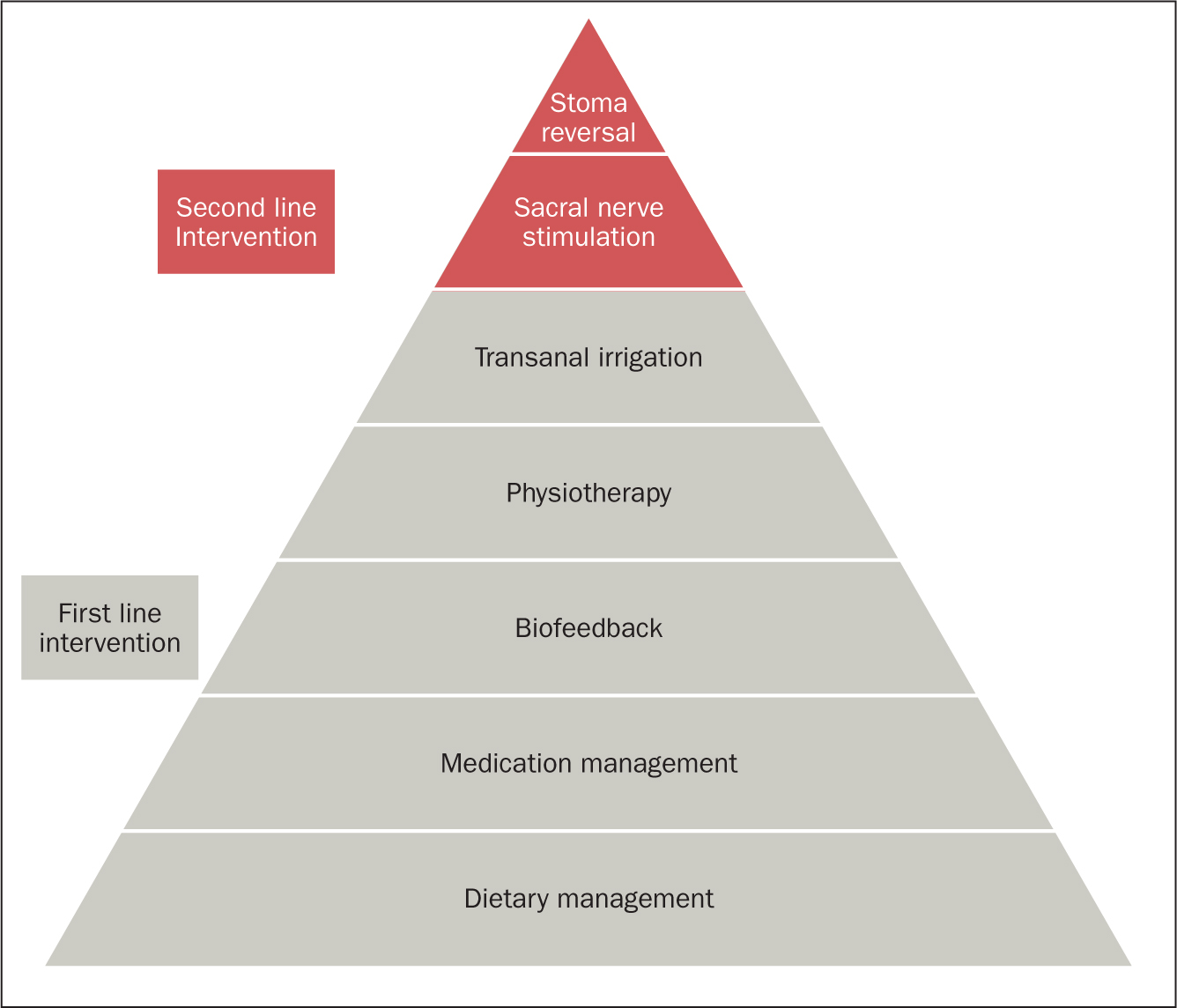

LARS is understood to be a result of various pathophysiological changes. When part of the rectum is removed during surgery there can be a reduction in the storage capacity of the rectum. This can lead to altered rectal compliance, meaning that the urge to defaecate can be prompted by a smaller volume of stool (Burch, 2021). There are a variety of management methods that can be employed to improve symptoms of LARS (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Management strategies for LARS (National Guideline Alliance, 2020)

Figure 1. Management strategies for LARS (National Guideline Alliance, 2020)

Management strategies

Conservative management consists of a range of first-line treatments and can include the following interventions:

- Dietary management: increasing intake of fibre-rich low-fat foods; avoiding wine, cold drinks and spicy foods (Christensen et al, 2021)

- Medication management: anti-diarrhoeal medications such as loperamide can be used to reduce frequency and improve consistency of stool (Christensen et al, 2021);

- Biofeedback therapy: to improve rectal co-ordination and sensation. A study into biofeedback as a management tool for LARS demonstrated a reduction in faecal incontinence impact scores, reduction in frequency of bowel movements and improvement in anorectal manometry values following a coordinated programme of biofeedback (Liang et al, 2016)

- Pelvic floor physiotherapy: to strengthen pelvic floor muscles with the aim of reducing episodes of faecal incontinence (Christensen et al, 2021)

- Transanal irrigation (TAI): to ensure that the rectum or neorectum (artificially made rectum) remains empty of stool, thereby reducing the urge and frequency of bowel movements along with episodes of faecal incontinence (Christensen et al, 2021).

When conservative measures have failed or are inadequate, more invasive treatments may be required, such as:

- Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS): may help to alter inappropriate or unwanted messages sent along sacral nerve pathways. The aim is to reduce incontinence episodes and increase the ability to defer defaecation

- Stoma reformation: in patients who remain symptomatically refractory to all other management methods.

Transanal irrigation for LARS management

TAI fits into the LARS treatment algorithm following, and often alongside, trial of all other conservative methods as outlined above. The use of TAI in patients with LARS was first described in 1989 (Iwama et al, 1989). Keeping the rectum or neo-rectum empty of stool can, in turn, impact on predictability of bowel movements, helping the patient to regain control over their bowels.

There is now a range of TAI products available. This specialist equipment allows the instillation of warm water into the rectum and descending colon; how far the water reaches will depend on the volume of water instilled. TAI can be categorised as either low volume (which in this case refers to less than 400 ml of water) or high volume (400 ml or more). TAI is thought to work by ‘flushing’ out the rectum and also by instigating peristalsis.

There is a choice of catheter or cone-based systems, which use a manual pump, gravity or electric pump to instil the water. Selection of the TAI system depends on various factors and algorithms have been developed to assist this decision-making process (Emmanuel et al, 2019). Most of all, the selected equipment should make the irrigation process as simple as possible, so that it can be incorporated easily into daily life.

The Durham bowel dysfunction service supports patients with symptoms of LARS. Referrals come from colorectal surgeons and colorectal specialist nurses. Patients will already have tried first-line conservative measures such as dietary changes and using anti-diarrhoeals such as loperamide, to slow the passage of stool through the colon. Following a thorough holistic assessment, patients embark on a personalised programme of treatment including biofeedback therapy and pelvic floor exercises to enable a better control of the stool. Education on optimum defaecation dynamics ensures that the patient is correctly positioned on the toilet while opening their bowel. This enables relaxation of the pelvic floor and so the maximum amount of stool can be expelled. This aims to safeguard against post-defaecation seepage, where any remaining stool is passed after leaving the toilet. Strengthening the pelvic floor muscles enables the patient to more effectively hold on to stool once they experience the urge to defaecate. If these measures fail to give adequate symptom control, TAI is commenced.

Service audit

A retrospective audit of 15 patients under the care of the bowel dysfunction service at County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust was performed. These patients had been started on TAI during the previous 4 years (2017-2020) for symptoms of LARS. They had a range of symptoms including frequency of defaecation, urgency, post-defaecation seepage and emptying difficulties. Information for the audit was retrieved from patient notes.

The purpose of this audit was to compare clinical outcomes for patients seen by this service with published evidence that TAI reduces both frequency of bowel movements and episodes of faecal incontinence (Koch et al, 2009; Sumner and Collins, 2019; National Guideline Alliance, 2020; Christensen et al, 2021). The authors also wanted to explore whether water volume affected these outcomes.

Results

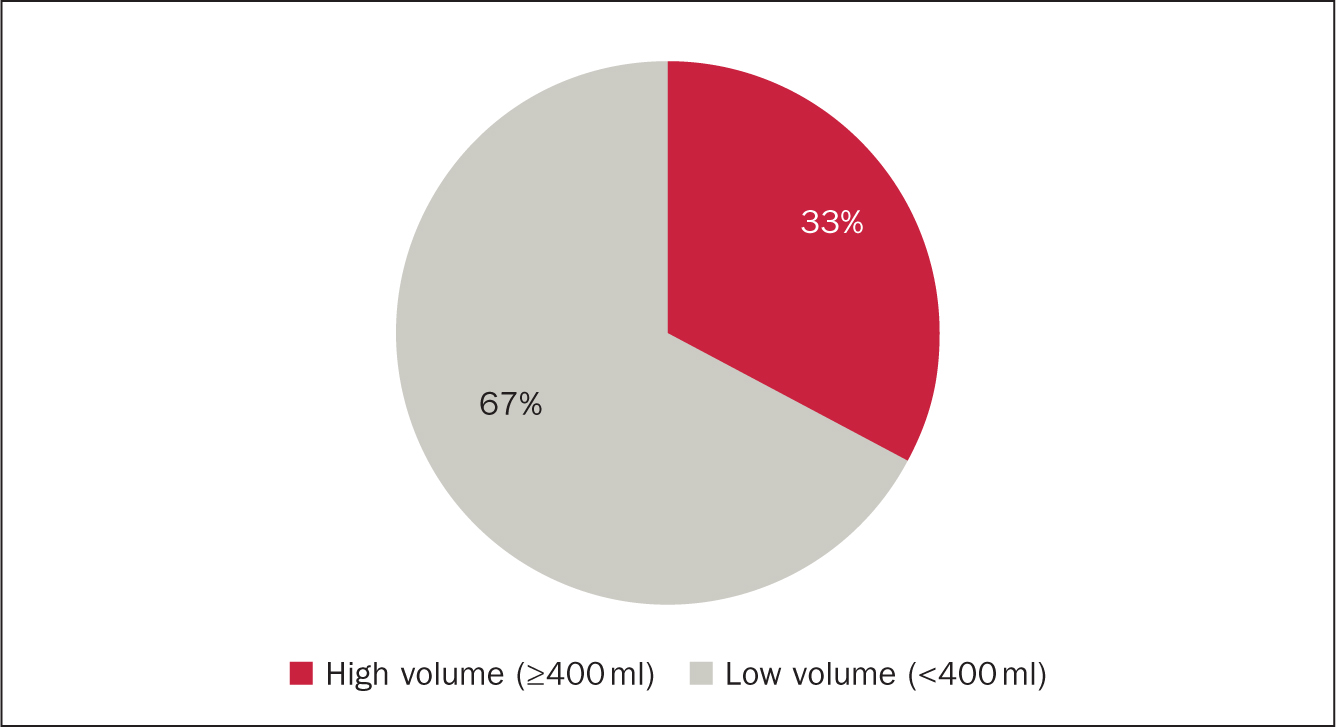

Data were collected on 12 patients. Three patients were withdrawn from analysis as a result of discontinuation of TAI before the point of audit. Two patients gave the reason for this as ‘takes too long to perform’ and ‘time consuming’. Interestingly both of these were using a low-volume system. The third patient had discontinued as their cancer had relapsed and they were now undergoing chemotherapy (a contraindication to TAI). Data analysis focused on 12 patients and key points are shown in Figures 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 2. High vs low-volume water use

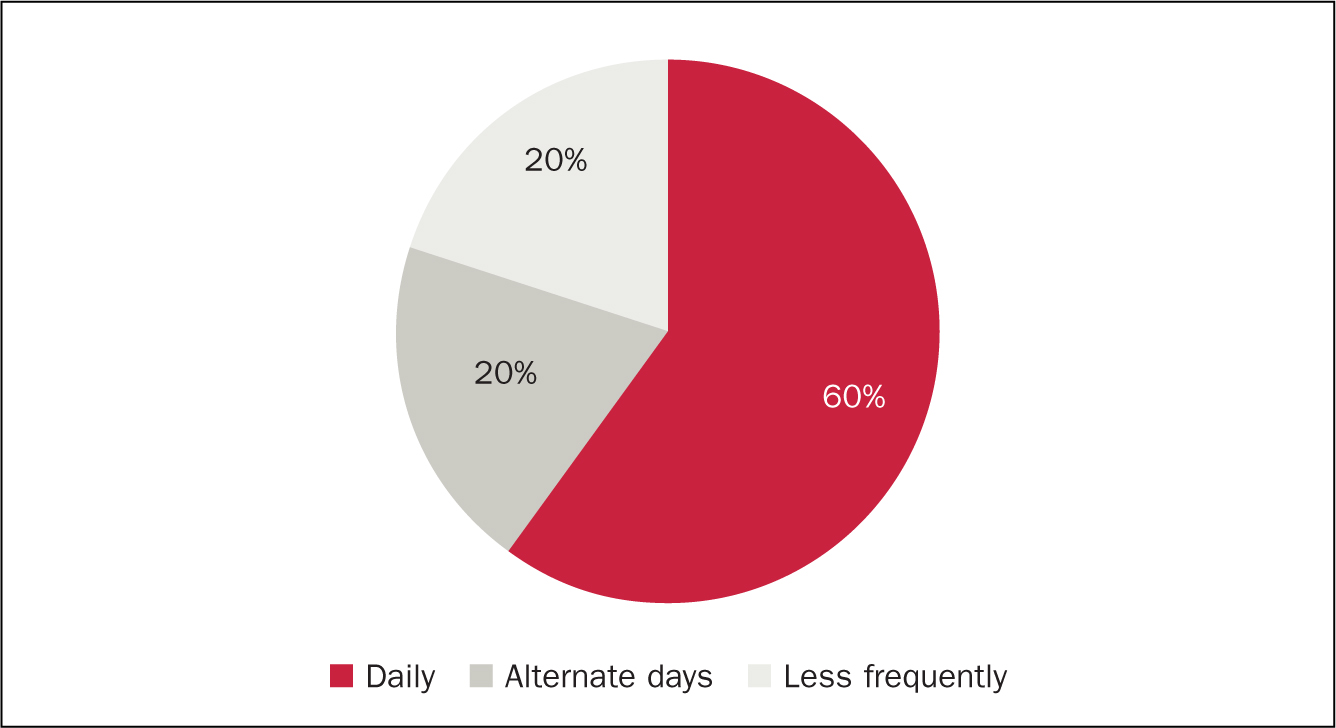

Figure 2. High vs low-volume water use  Figure 3. Frequency of TAI

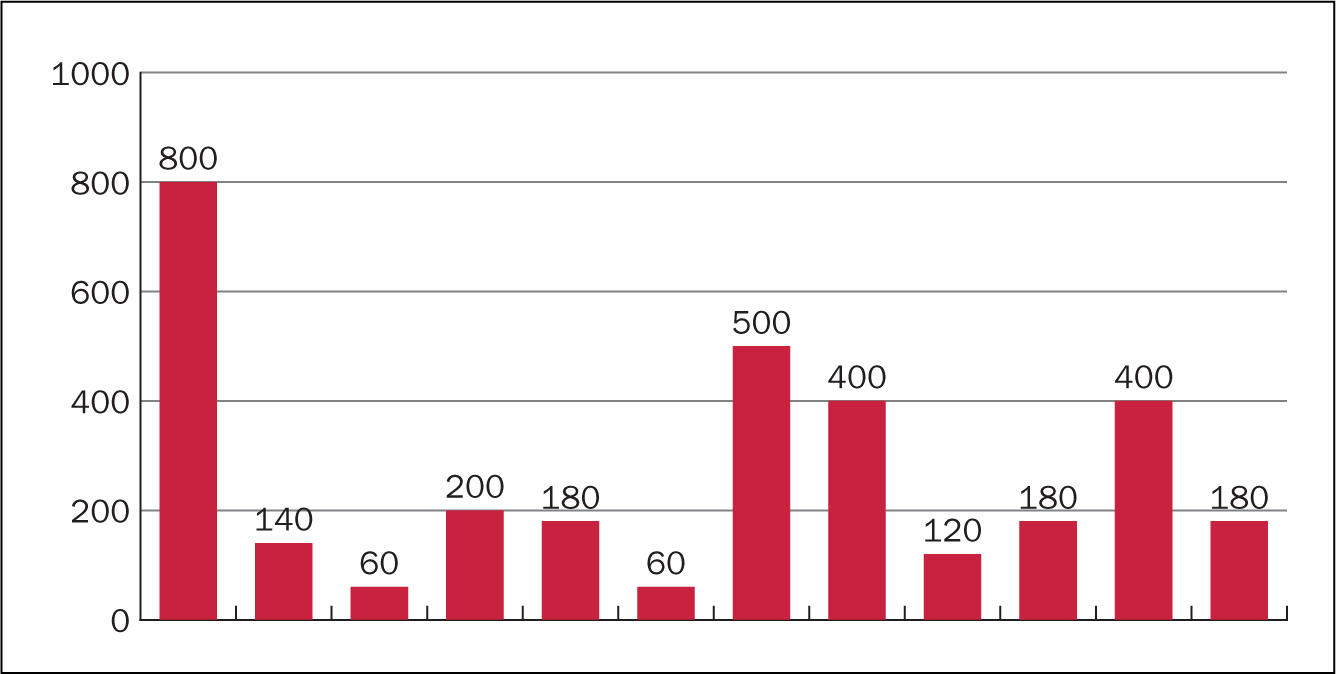

Figure 3. Frequency of TAI  Figure 4. Volume of water used (ml)

Figure 4. Volume of water used (ml)

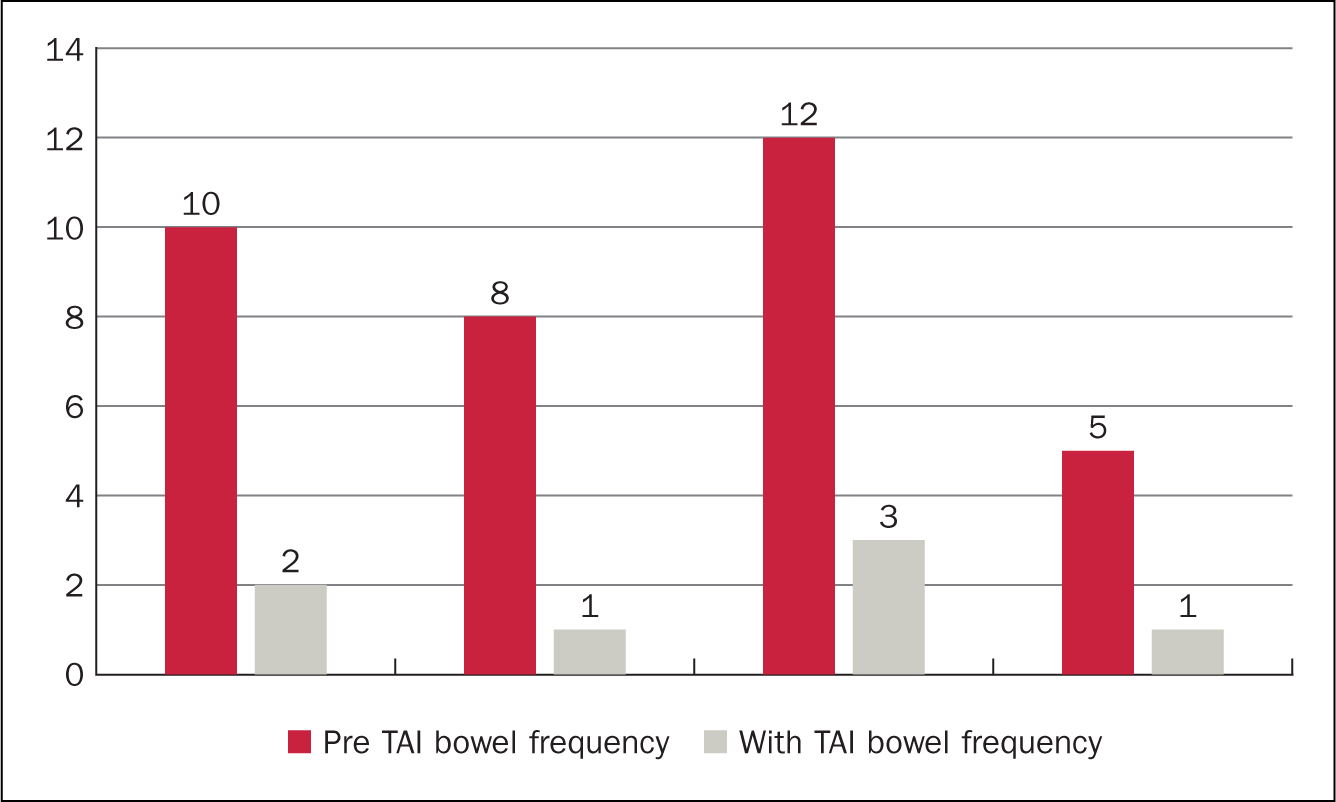

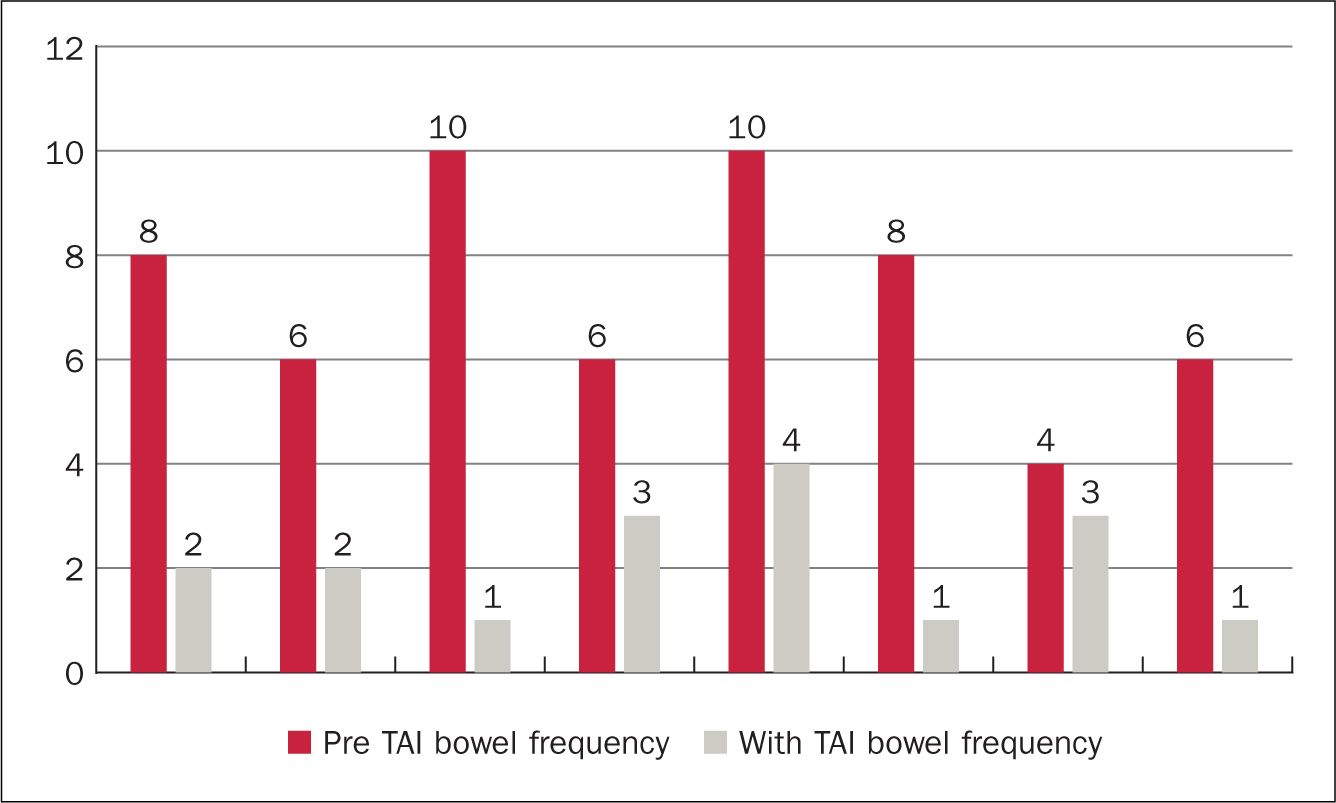

Figure 5 and Figure 6 demonstrate the impact of TAI on frequency of bowel movements. All 12 patients had a reduction in the frequency of bowel movements each day. Before starting to use TAI, the median bowel frequency was 8 times a day (range 4-12). This can be compared with median frequency while using TAI of 2 episodes a day (range 1-4), showing a median reduction of 6 episodes a day.

Figure 5. High-volume TAI impact on bowel frequency (episodes per day)

Figure 5. High-volume TAI impact on bowel frequency (episodes per day)  Figure 6. Low-volume TAI impact on bowel frequency (episodes per day)

Figure 6. Low-volume TAI impact on bowel frequency (episodes per day)

A difference between users of low and high-volume irrigation systems was observed: on average, patients using high-volume TAI had a greater pre-TAI frequency of bowel movements each day than those using low water volumes. Patients using high-volume systems also experienced a greater reduction in bowel movements a day than those using low-volume systems: high-volume median daily reduction in bowel movements was 7.5 (range 4-9) compared with low-volume average daily reduction of 5.5 (range 1-9) bowel movements. Three patients described episodes of faecal incontinence as part of their LARS symptoms. Of these, all three noticed that faecal urge incontinence and post-defaecation seepage stopped while using TAI.

Discussion

The results from this small retrospective audit show TAI may be beneficial for patients experiencing symptoms of LARS. Frequency of bowel movements were reduced for all users. This reduction was greatest in those patients using the highest volumes of water (400-800 ml). The numbers were small, only four of the twelve patients used high-volume TAI. Interestingly three of these had the highest frequency of pre-TAI bowel movements and therefore the greatest potential for improvement. Three patients experienced faecal incontinence before TAI. None of these patients had experienced faecal incontinence since initiating TAI, it was completely resolved.

The results of this small audit are in keeping with previously published research findings that show TAI is beneficial for LARS patients (Koch et al, 2009; Sumner and Collins, 2019; National Guideline Alliance, 2020; Christensen et al, 2021). However, research into the benefits of high-volume TAI versus low-volume TAI specifically relating to LARS symptom management is limited. This small audit suggests that further research into this area could be beneficial.

In clinical practice the authors would start with low-volume TAI, in keeping with best practice (Emmanuel et al, 2019) and then the patient would progress to higher volumes of water if improvement in LARS symptoms had not been observed. This audit shows that those patients using higher volumes of water were found to have a greater reduction in the frequency of daily bowel movements. It could be that higher volumes of water are required to irrigate further into the descending colon in order to provide the patient with longer time between bowel movements.

Patients who irrigated with higher volumes were also found to use TAI daily, which may have contributed to the improvement noticed. This may be due to the regular routine of irrigation washing out the rectum and stimulating peristalsis of the descending colon, allowing stool to be passed regularly with the rectum remaining stool free. Those patients who experienced faecal incontinence before beginning TAI also irrigated daily without exception. This audit suggests that daily irrigation is more effective for patients with LARS, perhaps due to consistent scheduled emptying of the rectum.

It is important also to look at the three patients who discontinued TAI. Although one discontinued due to progression of their cancer, two stopped because they felt that TAI was time consuming. Interestingly both were using low-volume systems, which health professionals often perceive as quick to use.

Conclusion

It is clear that there are benefits in using TAI for LARS; however, TAI requires commitment and motivation from the patient. The practitioner being aware of the benefits of TAI and sharing this through enthusiasm and regular support can enable the patient to overcome difficulties as they arise (if they arise). If patients perceive TAI to be beneficial, they will be motivated to continue with TAI and try to overcome any barriers, such as the time commitment required. Where TAI is not available practitioners should be able to signpost to local services that can meet this need.

KEY POINTS

- Many patients struggle with bowel symptoms as a result of their surgery for bowel cancer

- Transanal irrigation (TAI) is an effective management strategy for low anterior resection syndrome (LARS)

- The audit data indicates that TAI reduces frequency of bowel movements in patients with LARS

- TAI also reduces faecal incontinence in patients with LARS

CPD reflective questions

- What are the symptoms and consequences of low anterior resection syndrome?

- Can you identify any patients who could benefit from using transanal irrigation (TAI)?

- How would you describe the benefits of TAI to a patient?