Cancer is a significant public health concern worldwide, with a steadily increasing incidence. In 2022, the incidence for all cancers in both sexes was recorded at almost 20 million, with nearly 10 million cancer-related deaths occurring worldwide (International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), 2025a). In Oman, in 2022, the number of new cancer cases was 4045, with 2261 recorded deaths (IARC, 2025b).

Oncology patients often experience multiple physical, emotional and psychological challenges throughout their cancer treatment journey. Among the various psychological impacts, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has emerged as a noteworthy concern in this vulnerable population.

PTSD is a complex mental health condition that typically arises from exposure to or experience of a traumatic event. While it has traditionally been associated with combat veterans and survivors of violent incidents, PTSD is now recognised as a potential psychological consequence of cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Oncology patients undergo distressing experiences, such as receiving life-altering diagnoses, undergoing invasive treatments, coping with treatment-related side-effects and confronting uncertainties about their future health and wellbeing (Cordova et al, 2017; Liegey Dougall et al, 2017). These experiences can trigger a range of emotional responses and adaptive behaviours that resemble the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, negatively affecting their quality of life (QoL).

QoL is a multidimensional construct that encompasses an individual's physical, emotional, social and functional wellbeing. In the context of oncology, maintaining a satisfactory QoL is paramount, because it directly affects treatment adherence, disease management and overall patient outcomes (Haddou Rahou et al, 2016). Understanding the relationship between PTSD and QoL among oncology patients is crucial for health professionals if they are to develop comprehensive patient-centric treatment approaches.

Additionally, psychological distress, which can involve intrusive thoughts, nightmares and hyperarousal, can significantly impede a patient's ability to cope with cancer-related challenges, leading to increased emotional distress and a diminished QoL.

For instance, a descriptive cross-sectional survey study was conducted to assess the QoL and PTSD symptoms among women cancer patients (Maraqa and Ahmead, 2021). This study found significant negative relationships between PTSD and QoL in terms of physical, role, social and emotional functioning. It also indicated that a better QoL was associated with lower PTSD symptoms (Maraqa and Ahmead, 2021). Another study showed that the worsening of PTSD symptoms among patients with lung cancer over 6 months from diagnosis was associated with a deterioration in QoL (Ni et al, 2018). Patients with PTSD have poor health-related outcomes, including weak adherence to cancer treatment (Rustad et al, 2012).

Moreover, social support has been suggested to play a mediating role in the development of PTSD symptoms in breast cancer patients (van Oers and Schlebusch, 2021). A lack of social support has been identified as a risk factor for more severe PTSD symptoms. Social support from various sources in the patient's social network, such as family, intimate partners and friends, is a powerful emotion regulator in traumatic and stressful situations, and may help protect against cancer-related PTSD (Charuvastra and Cloitre, 2008; Gottlieb and Bergen, 2010). In patients with cancer, a lack of social support has been reported as a strong predictor of psychological comorbidity, including PTSD symptoms (Mehnert and Koch, 2008). Perceived social support acts as a buffer, allowing patients to cope with the negative impacts of various stressful circumstances during their illness (Costa-Requena et al, 2014).

Previous studies have established a negative association between PTSD and QoL in patients with cancer (Ni et al, 2018; Maraqa and Ahmead, 2021), however, the majority have primarily concerned the direct relationship between PTSD and QoL without examining potential mediating mechanisms. Additionally, much of the existing research on PTSD has focused on populations affected by war, natural disasters or other traumatic events rather than cancer-related trauma (Schnurr et al, 2009; Zhou et al, 2010. Although studies have acknowledged the significance of social support in mitigating PTSD symptoms (van Oers and Schlebusch, 2021; Zhang et al, 2021), they have largely examined it as a general protective factor rather than an active mediator in the PTSD-QoL relationship among oncology patients.

Moreover, some studies have explored the link between social support and QoL in cancer (Ban et al, 2021), but they have often failed to account for PTSD as a potential influencing factor, leaving a critical gap in the understanding of how psychological distress affects patient wellbeing. Given that PTSD symptoms can significantly affect treatment adherence, emotional regulation and coping mechanisms in cancer patients, there is a pressing need to examine whether social support can buffer these effects and improve QoL.

The present study addresses this gap by empirically testing the mediating role of social support in the PTSD-QoL relationship, thus providing a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between psychological distress and social resources in cancer care.

Hypotheses

The null hypothesis (H0) is: social support does not mediate the relationship between PTSD and QoL among oncology patients.

The alternative hypothesis (H1) is: social support mediates the relationship between PTSD and QoL, meaning that higher levels of social support are associated with better quality of life despite PTSD symptoms.

Methods

Design

A descriptive correlation cross-sectional design was used.

Settings

The study was conducted across three tertiary hospitals in Muscat, Oman, which primarily cater to cancer patients from all regions of the Sultanate of Oman and serve as their primary treatment and follow-up centres.

One of these hospitals specialises in cancer care and research (hospital A), the second is a university-affiliated facility that provides healthcare services to patients with haematological cancers (hospital B) and the third is a governmental institution offering comprehensive cancer care (hospital C).

Sample, sampling and sample size

The sample comprised patients with cancer who had received treatment in these hospitals. Participants were enrolled in the study using convenience sampling, which was chosen for its practicality in accessing a diverse group of oncology patients across the three hospitals. Data were collected between January 2023 and July 2023.

Given the time constraints and ethical considerations of recruiting vulnerable populations, this approach enabled efficient data collection while ensuring a sufficient number of participants met the eligibility criteria for mediation analysis. To mitigate potential biases associated with convenience sampling, participants were recruited from multiple hospitals to enhance the sample heterogeneity and improve generalisability. Furthermore, validated instruments were employed to minimise measurement bias, and trained researchers ensured consistency in the data collection.

All Omani adult patients aged ≥18 years with a cancer diagnosis of at least 3 months (as indicated by the histopathology report in their medical records) and registered at any of the designated healthcare establishments met the criteria for potential inclusion in the study. Exclusion criteria included individuals diagnosed with cancer less than 3 months before the start of the study, those previously diagnosed who were not undergoing active treatment, individuals with a documented history of psychiatric disorders such as depression or anxiety as identified from their medical records, those with cognitive impairments. and those with severe fatigue or acute symptoms.

Sample size

The sample sizes were calculated to meet the requirements essential for conducting mediation analysis, specifically the Sobel test. For these calculations, the authors used G*Power v3.1 and input the following parameters: 80% power; a medium-sized effect; and an alpha level of 0.05. This yielded the minimum required sample size of 89 participants. This study included 343 patients, indicating a large sample size.

Instruments

Self-administered questionnaires were used to gather data for this study and are discussed below.

Demographics data sheet

The demographics data sheet elicited data on patients' age, sex, marital status, employment status, income and level of education.

Information on cancer characteristics was also collected, including diagnosis date, type of cancer, disease stage, treatment type, family history of cancer, number of emergency department visits in the preceding 3 months, number of hospitalisations in the preceding 3 months and the total number of days spent as an inpatient.

Post-traumatic stress disorder checklist

The PTSD Checklist 5 (PCL-5) is a self-report measure of PTSD used widely in both clinical and research settings (Blevins et al, 2015). It is a validated self-report tool based on the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria (Blevins et al, 2015). The PCL-5 comprises 20 items, each rated on a scale of 0–4, with 0 indicating ‘not at all’ and 4 indicating ‘extremely’.

A PCL-5 score can be calculated in two ways. The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria require at least one B item (1–5), one C item (6–7), two D items (8–14) and two E items (15–20) with a score of two or higher. Alternatively, a total score within a range of 0–80 can be calculated to reflect symptom severity. A cut-off score in the range of 28–37 for diagnosing PTSD is recommended (Blevins et al, 2015; Ashbaugh et al, 2016), while the US Department of Veterans Affairs recommends a cut-off score of 32 (Blevins et al, 2015). This study employed symptom cluster criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD, as per the DSM-5.

The PCL-5 demonstrated excellent internal consistency (alpha 0.94) and test-retest reliability (r =-0.82). It also exhibited robust convergent validity (r=0.74–0.85) (Blevins et al, 2015). An Arabic translation of the PCL-5 (Ibrahim et al, 2018) has shown good internal consistency (alpha 0.85) and adequate convergent validity, indicating the suitability of the PCL-5 for Arab populations.

Core QoL questionnaire

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) was used to assess QoL. In 1986, the EORTC initiated a research programme to develop a comprehensive and modular approach for assessing the QoL of cancer patients. The first questionnaire, the EORTC QLQ-C36, was introduced in 1987 and was designed to be cancer specific, multidimensional and suitable for self-administration. After further refinement, the second-generation core questionnaire, the EORTC QLQ-C30 v1, was developed in 1993 (Aaronson et al, 1993). The questionnaire incorporates 30 items that evaluate five functional dimensions (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), three symptom dimensions (fatigue, pain and nausea/vomiting), global QoL and various single items to assess common symptoms reported by cancer patients (eg dyspnoea, loss of appetite, insomnia, constipation and diarrhoea).

This study used the EORTC QLQ-C30 v3.0. The responses to the questionnaire are scored on a scale of 0–100, with higher scores indicating better functioning and QoL. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is considered reliable and valid for measuring the QoL of cancer patients in diverse clinical research settings, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of ≥0.70 (Aaronson et al, 1993).

The Arabic version is available on the EORTC website (https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaires). A Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.927 for the Arabic version has been reported, indicating high internal consistency (Jassim and AlAnsari, 2020).

Perceived social support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) questionnaire (Zimet et al, 1988) was used to assess social support.

It comprises 12 items divided into three subscales: family support (items 3, 4, 8 and 11); friend support (items 6, 7, 9 and 12); and other support (items 1, 2, 5 and 10). The 12-item MSPSS employs a 7-point, Likert-type response format (from 1=very strongly disagree to 7=very strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater social support (Zimet et al, 1988).

This three-factor construct exhibits robust internal consistency and test–retest reliability (Clara et al, 2003). Merhi and Kazarian (2012) evaluated MSPSS in a Lebanese adult population, yielding an internal consistency coefficient (alpha) of 0.87. This indicates that the Arabic version of the MSPSS is a dependable, valid measure of social support in Lebanon (Merhi and Kazarian, 2012).

Data collection procedure

Institutional review board approval was obtained from all three hospitals. The researcher printed and coded the questionnaires, the participant information sheets and the consent forms. To familiarise themselves with the schedule and introduce the study to the nurse in charge, the researchers (HAA, MAQ, SA) visited the designated settings. Before each data collection visit, the researcher reviewed the patients' records to verify diagnoses and eligibility. The researcher engaged with the head nurses of the wards to elucidate the study's objectives and procedures. and to compile a list of patients along with their medical record numbers.

Subsequently, eligible patients were approached and the study explained to them, covering its purpose, objectives and potential benefits. They were informed of their right to decline participation and were reassured about the voluntary nature of their involvement. If they agreed to take part, they were asked to sign a consent form and complete the questionnaires.

Participant identities were kept anonymous, and data access was confined to the researcher and supervisor. Consent forms were securely stored (see below).

The researcher was on hand, as participants completed the questionnaires to answer any enquiries and subsequently collected and secured the completed questionnaires.

Ethical considerations

The research team secured approval from the ethics committees of all three institutions. They personally conveyed comprehensive information regarding the study, including its title, objectives and anticipated outcomes, to the participants. The patients were made aware that their participation was entirely voluntary, that they retained the right to decline involvement and that they could withdraw at any time. Consent forms were provided to those who agreed to take part.

The research team assured the participants of their complete anonymity and ensured data protection by storing their information within a securely locked cabinet and a computer with password protection. In addition, no identifiable data were collected, and only aggregate data were published. Data access was limited exclusively to the research team, and external individuals were not granted authorisation to access it.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS v25. The study employed descriptive analysis, including frequency, mean and standard deviation (SD), to summarise participants' demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as to assess the prevalence of PTSD, level of perceived social support and quality of life.

Based on the central limit theorem and the relatively large sample size, the data distribution was assumed to be normal (le Cessie et al, 2020). Therefore, an unpaired t-test was used to assess the difference in mean social support and quality of life with regard to PTSD status.

The Sobel test was used to assess the significance of social support as a mediator between PTSD and QoL. This is a widely accepted method for testing indirect effects in mediation analyses. The authors also used bootstrapped confidence intervals, a more robust approach that does not rely on strict distributional assumptions and is recommended for mediation analysis (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

Results

Sample characteristics

Most patients were outpatients (n=313; 91.3%), and 247 (72%) were female. Average patient age was 47.3 years (SD=13.5). The majority (75.2%) of the participants were married (n=258), and more than half had completed secondary school education or had a lower level of education (n=204; 59.5%); 32.7% of participants were employed (n=112); and average monthly income was 836 Omani rials (SD=675) (£1630; SD=£1316 [exchange rate at time of publication]). Detailed participant demographics are provided in Table 1.

| Variable | Frequency (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital* | ||

| A | 22 (6.4) | |

| B | 127 (37) | |

| C | 194 (56.6) | |

| Type of patient | ||

| Inpatient | 30 (8.7) | |

| Outpatient | 313 (91.3) | |

| Age (years) | 47.2 (13.5) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 96 (28) | |

| Female | 247 (72) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 258 (75.2) | |

| Not married | 85 (24.8) | |

| Educational level | ||

| Secondary school and below | 204 (59.5) | |

| Diploma and above | 139 (40.5) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 112 (32.7) | |

| Unemployed | 231 (67.3) | |

| Monthly income (Omani rials) † | 836 (675) | |

Most participants had a solid cancer (n=314; 91.5%), and a significant proportion had cancer at an advanced stage (n=169; 53.7%) (Table 2). The time since diagnosis ranged between 3 and 120 months, with an average of 21 months (SD=21.0), with the types of therapy administered broken down as follows:

| Variable | Frequency (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | ||

| Haematological | 29 (8.5) | |

| Solid | 314 (91.5) | |

| Stage of cancer* | ||

| Early stage | 146 (42.6) | |

| Advanced | 169 (49.3) | |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 270 (78.7) | |

| No | 73 (21.3) | |

| Number of chemotherapies received | 9.6 (8.9) | |

| Hormonal | ||

| Yes | 111 (32.4) | |

| No | 232 (67.6) | |

| Immunotherapy | ||

| Yes | 84 (24.5) | |

| No | 259 (75.5) | |

| Target therapy | ||

| Yes | 30 (8.7) | |

| No | 313 (91.3) | |

| Palliative care | ||

| Yes | 8 (2.3) | |

| No | 335 (97.7) | |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 113 (32.9) | |

| No | 230 (67.1) | |

| Cancer-related surgery | ||

| Yes | 220 (64.1) | |

| No | 122 (35.6) | |

Furthermore, 64.1% (n=220/343) of patients had undergone cancer-related surgery.

The data collected showed that 77.8% (n=267) of participants had not visited the emergency department and 30.9% (n=106) had been admitted to a hospital at least once within the preceding 3 months; 28.3% (n=97) had a family history of cancer; and 12% (n=41) had been referred for psychiatric evaluation.

Social support

Using to the symptom cluster criteria for PCL-5, the study found that 94 (27.4%) patients met the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. Regarding social support, the mean total score on the MSPSS was 69.0 (SD=11.6) of 84.

An unpaired t test was conducted to assess potential differences in the distribution of the mean total scores for social support and PTSD. The results indicated that participants with PTSD (mean=66.0; SD=10.8) had a significantly lower mean total social support score than those without PTSD (mean=73.1; SD=12.9) (t=3.5; df=145.5; 95% CI (2.29–8.19); P=0.001).

Quality of life

The mean total score for the overall QoL subscale were as follows: functional subscale 70.0 (SD 22.6); 26.6 (SD=18.6) for the total symptom's subscale; and 74.2 (SD=21.9) for global health status/QoL. Unpaired t-tests were conducted to compare the mean scores between patients with and without PTSD for the overall function subscale, total symptoms subscale and global health status/QoL subscale.

The results indicate that patients with PTSD had significantly lower mean scores on all three subscales (P<0.05) (Table 3). These findings suggest that patients with PTSD experience poorer global health status/QoL, greater functional impairment and more symptoms than those without PTSD.

| Quality of life subscale | PSTD | 95% CI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | t | df | P value | Lower | Upper | |

| Mean (SD) | |||||||

| Total symptoms | 42 (17.2) | 21.2 (15.8) | -10.52 | 340 | 0.001* | −24.60 | -16.85 |

| Total functional | 54.6 (21.2) | 81.6 (17.1) | 11.05 | 141 | 0.001* | 22.11 | 31.75 |

| Global health | 55.5 (22.4) | 75.5 (20.1) | 7.91 | 341 | 0.001* | 14.94 | 24.82 |

CI=confidence interval, PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder

Mediating role of social support

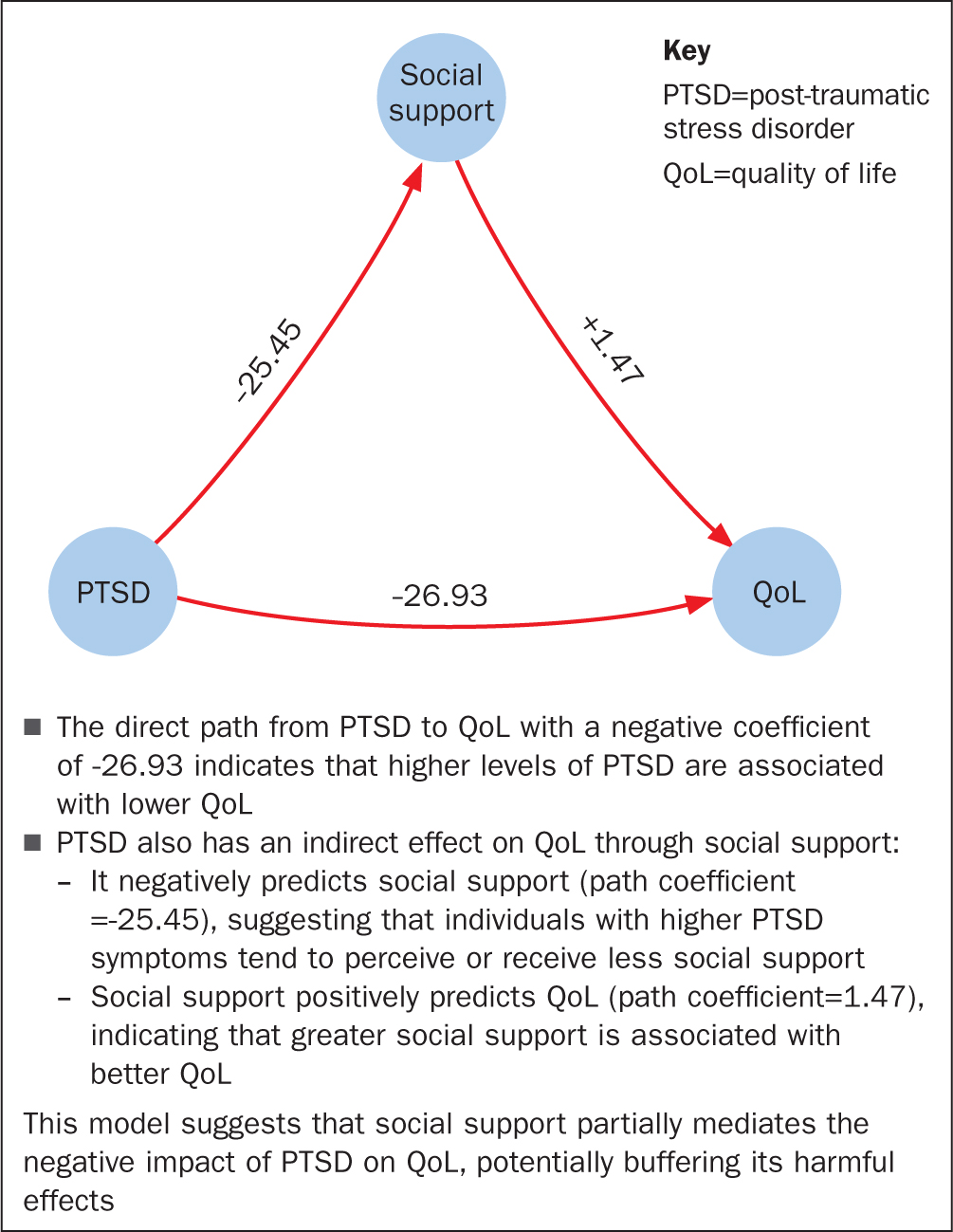

The mediating role of social support in the relationship between PTSD and QoL in patients with cancer was assessed using the Sobel test. The results, presented in Table 4 and Figure 1, indicate that the total, direct and indirect effects were significant for all three QoL scales (total symptoms, total functional and global QoL) (P<0.0001).

| Outcome | Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | T value | P value | 95% CI | |

| Total symptom QoL | 20.73 | <0.0001 | 19.36 | <0.0001 | 1.37 | -3.4 | <0.001 | -0.41,-0.11 |

| Total function QoL | -26.93 | <0.0001 | -25.45 | <0.0001 | 1.47 | 3.3 | <0.001 | 0.11–0.45 |

| Global QoL | -19.88 | <0.0001 | -17.56 | <0.0001 | 2.31 | 4.6 | <0.0001 | 0.25–0.63 |

CI=confidence interval, PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder, QoL=quality of life

Specifically, the indirect effect of PTSD on the total symptom score through the mediator variable of social support was significant (effect 1.37; standard error (SE)=0.66; 95% CI (-0.41, -0.11)). Similarly, the indirect effect of PTSD on the total functional scale through social support was significant (effect 1.47; SE=0.70; 95% CI (0.11–0.45)). Furthermore, the indirect effect of PTSD on global QoL through social support was also significant (effect 2.31; SE=0.90; 95% CI (0.25–0.63)). These findings underscore the vital role of social support as a mediator in the relationship between PTSD and QoL.

Discussion

This study found a significant contrast between cancer patients with and without PTSD in terms of their reported levels of perceived social support and QoL. Moreover, the outcomes underscore the pivotal role of perceived social support as a mediating factor in the intricate connection between PTSD and QoL. It is noteworthy that robust social support mitigated the adverse effects of PTSD on overall QoL.

When discussing the correlation between PTSD and social support, the findings of this study are consistent with those of prior research (Liu et al, 2015; Yang et al, 2016; Liu et al, 2017; Wang et al, 2021). It is worth emphasising that the level of social support observed in the present study appears to be higher than that previously documented. This observation can be attributed to the cultural values prevalent in Eastern Muslim countries such as Oman, where there is a strong emphasis on family bonds and a deep sense of obligation towards relatives, often intertwined with religious convictions (Al-Azri et al, 2021).

In these cultural contexts, especially when confronted with challenging circumstances and traumatic experiences, family members typically rally round to provide mutual support (Al-Azri et al, 2021). Consequently, the family assumes a pivotal role as a significant source of support, offering both emotional and practical aid to individuals, particularly during times of illness. This collective familial support acts as a potential buffer against the onset of PTSD as individuals find solace in the assistance and understanding they receive from their loved ones.

The findings indicated that patients with cancer who experienced PTSD had significantly poorer global health status/QoL, greater functional impairment and more symptoms than those without PTSD. This means that patients with cancer who experience PTSD symptoms tend to have worse overall health and QoL. They may also have more difficulties in performing daily activities and experience more physical and psychological symptoms than those without PTSD. A small number of studies have investigated the impact of PTSD on the QoL of patients with cancer, and the results are consistent with the present findings, indicating that patients with cancer-related PTSD have a poor QoL (Gold et al, 2012; Ni et al, 2018; Maraqa and Ahmead, 2021). For example, patients with cancer and PTSD symptoms have been found to have lower QoL scores than those without such symptoms (Gold et al, 2012). Similarly, patients diagnosed with lung cancer who experienced symptoms of PTSD over a 6-month period also saw a decline in their QoL, suggesting that the worsening of PTSD symptoms is associated with a reduction in their QoL (Ni et al, 2018).

A recent study found that the QoL of women who have been diagnosed with cancer is generally poor and strongly associated with PTSD (Maraqa and Ahmead, 2021). It is evident that patients with cancer can experience a significant decline in their QoL because of the disease and its treatment (Al Qadire et al, 2020; 2022). This decline can manifest in various ways, for example psychological distress, physical symptoms and impaired functioning. Moreover, the authors' findings indicate that patients who develop PTSD symptoms following a cancer diagnosis may experience an even greater decline in QoL.

Finally, when the authors combined the three variables of PTSD, social support and QoL, they observed that social support mitigated the impact of PTSD, potentially reducing the likelihood of PTSD occurrence. A review of the evidence indicates that the mediating role of social support between PTSD and the QoL of patients with cancer has not been explored previously; to date, no similar study on this topic has been published as far as the authors can ascertain. This gap underscores the novelty and significance of the present study. The findings of this study provide encouraging evidence for increased investment in social support to enhance patient outcomes, particularly in terms of QoL, which may also offer a preventive or protective effect against the development of PTSD. These aspects are the key areas for further investigation.

Health professionals should actively promote the engagement of cancer patients with social support resources. This support can originate from diverse sources, including family, friends, health professionals and support groups, which provide emotional, informational and practical assistance. This support aids patients in effectively managing the stress associated with their illnesses. Subsequent research should acknowledge the pivotal role of this support, as its nature can significantly influence its effectiveness as a protective measure against PTSD, in line with Yang et al (2016).

This study highlights the role of social support in the Omani cultural context, but its implications extend beyond regional boundaries. Social support is a universally recognised factor in mitigating psychological distress and improving health outcomes across diverse healthcare systems. In countries with different cultural frameworks, formalised support structures such as patient advocacy programmes, psychosocial oncology services and technology-enabled peer support groups may serve a similar function in enhancing the QoL of cancer patients with PTSD. Additionally, integrating mental health screening into routine oncology care could be a valuable strategy worldwide to ensure early identification and intervention for PTSD symptoms.

Future research should explore how various healthcare policies, social welfare systems and cultural perceptions of mental health influence the effectiveness of social support interventions in different global settings.

Limitations

It is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations when interpreting the findings of this study. The data collection method employed relied on self-reported responses, which could potentially lead participants to provide socially desirable answers, particularly when it comes to indicating positive responses regarding social support and QoL.

There is also a possibility that participants may have intentionally downplayed psychological and mental symptoms because of the prevalent stigma associated with such issues, particularly within Middle Eastern countries and relatively tight-knit communities such as Oman.

The cross-sectional nature of this study limits its ability to establish causality between PTSD, social support and QoL. Although mediation analysis provides insights into potential relationships, it does not confirm the temporal sequencing or long-term effects.

Future studies should employ longitudinal or experimental designs to better assess the causal links and the sustained impact of social support interventions over time.

A key limitation of this study is its strong emphasis on cultural factors, particularly the role of family and community-based support in Oman. Although these findings provide valuable insights, the extent to which they can be generalised to countries with different social structures and healthcare policies remains unclear. Future studies should investigate how institutional and governmental support systems contribute to mitigating PTSD in patients with cancer outside the Middle Eastern context.

Implication for clinical practice

This study highlights the crucial mediating role of social support in alleviating PTSD symptoms among patients with cancer and enhancing their QoL. This presents a valuable opportunity for health professionals, particularly oncology nurses, to educate both patients and their families on the significance of social support. Furthermore, practitioners can assist in facilitating access to support groups and resources.

Oncology nurses and other health professionals can integrate these findings into their interventions by working with families and support groups. This could help develop effective strategies to augment social support for patients.

The findings of this study underscore the importance of adopting a comprehensive approach to address the physical and emotional symptoms experienced by patients with cancer, which detrimentally affect their quality of life. This necessitates a multidisciplinary approach involving professionals, such as psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers. Doing this can ensure cancer patients receive holistic care.

Conclusion

Patients with PTSD experience poorer social support and quality of life than those without PTSD. Social support appears to mediate this relationship, suggesting that it can improve overall wellbeing.

These findings suggest investment should be made in social support resources to improve patient outcomes and mitigate against the risk of developing PTSD. Health professionals should promote social support and technology-based assistance. This will create a strong social support system for cancer patients.

Future research could use longitudinal approaches to better understand the relationship between PTSD, social support and QoL over time. Additionally, studies in different healthcare settings and cultural contexts would help to clarify how various support systems influence these outcomes.