Monitoring fluid balance through accurate documentation of patients' intake and output charts is vital during hospitalisation and is a critical component in the care of acutely ill hospitalised patients, as well as part of providing safe patient care (Georgiades, 2016; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2017). Fluid balance monitoring has been reported to be a challenging task, especially when patients are confused, uncommunicative and incontinent (Vincent and Mahendiran, 2015). As a result, inaccurate fluid balance monitoring and poor documentation can lead to poor clinical outcomes in the acutely ill hospitalised patient, including missed recognition of warning signs of dehydration, affected cardiac and renal function, prolonged hospitalisation and increased mortality (Grams et al, 2011; NICE, 2017; Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, 2018). Fluid balance and monitoring has been recognised by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) as one of the critical factors relevant to quality patient care during hospitalisation (Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, 2018). It is well documented that the current practices of fluid intake and output monitoring for inpatients is inconsistent, incomplete and lacks accuracy (Shepherd, 2011; Eastwood et al, 2012; Nazli et al, 2016;).

According to the Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust (2015), fluid balance monitoring should be undertaken in patients with specific clinical indications such as heart failure and kidney issues (See Table 1). In addition, fluid balance monitoring is critical for patients who require acute-care monitoring due to other clinical indications, including those with increased losses, decreased intake and possible risk of third spacing conditions (a decrease in intravascular volume owing to movement of fluid into other extracellular spaces) (Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust, 2015). These outlined clinical indications highlight the importance of evaluating a patient's fluid balance status, as any signs of imbalances will require immediate interventions to prevent the complications of hypovolaemia and hypervolaemia. Despite the importance of ensuring fluid balance monitoring is carried out for those with clinical indications, it is also deemed unnecessary for patients who do not require acute-care monitoring because they have no acute onset of disease, are at the very end of life or are due for discharge (McGloin, 2015; Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust, 2015). However, previous research showed that patients were often placed on daily fluid balance monitoring when there were no clinical indications, leading to a waste of time and effort for the nursing team (Vincent and Mahendiran, 2015). Furthermore, a lack of communication and guidance from the medical team often results in nurses continuing unnecessary patient monitoring for longer than required (Vincent and Mahendiran, 2015).

Table 1. Operational definition of clinically indicated fluid monitoring

| Patient group | Details |

|---|---|

| Patients with increased fluid losses |

|

| Need for recording fluid losses |

|

| Patients with decreased fluid intake |

|

| Patients at risk of third spacing of fluid |

|

| Patients receiving drugs that may cause acute kidney injury |

|

| Patients with acute heart failure |

|

Staff shortages, time constraints and inadequate training were also cited as common barriers to accurate fluid balance monitoring and documentation in the acute care settings (McGloin, 2015; Vincent and Mahendiran, 2015). Fluid balance monitoring is highly time consuming, and its documentation is often given a low priority due to low staffing ratios (Vincent and Mahendiran, 2015). Current education on fluid balance monitoring appears insufficient to foster safe and effective practice, especially among those who are responsible for the majority of intake and output monitoring. In addition, ignorance of the reasons for prescribing IV fluid also contributes to this problem.

In most clinical settings, fluid balance monitoring is initiated by doctors (McCrory et al, 2017); however, in Singapore General Hospital, both doctors and nurses may initiate it. It was unclear if the current fluid balance monitoring practices were always appropriate and necessary.

Aim

This audit aimed to review the current practice of prescribing and monitoring of fluids and the documentation of fluid intake and output in hospitalised patients by assessing the appropriateness and accuracy of the documentation.

Methods

A retrospective review of the electronic records of a random sample of 2199 patients admitted at an acute care hospital in Singapore for 7 months between January 2017 and July 2017 was conducted. Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review board (ref: 2017/2865). The data were extracted and sent via several password-locked files to a hospital representative who was not involved in the study and not in the same department as the research team. This person was responsible for removing any patient-identifying information to maintain the anonymity of participants. The merged and anonymised data sets were sent in several password-locked files back to the research team.

Review of the anonymised electronic fluid balance charts was undertaken by two members of the study team. Data were extracted using a standardised data collection form. The following information was retrieved for each patient:

- Was daily fluid balance monitoring clinically indicated, based on the operational definitions by the Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust (2015) (Table 1)?

- Was daily fluid balance monitoring prescribed by the doctors or initiated by the nurses?

- Was the daily fluid balance documentation accurate for the entire admission?

To determine documentation accuracy, both intake and output (urine, bowel and vomit) were assessed:

- Oral fluids recorded in ml

- Intravenous fluids recorded in ml

- Output recorded in ml.

Each quantifiable amount (eg urine 100 ml) entered in the intake and output chart was considered as one accurate count. Each non-quantifiable entry documented (eg void in toilet) was considered as one inaccurate count. The total accurate counts divided by the total intake and output counts (in percentages) was used to determine the overall accuracy of documentation. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the audit results, using frequencies (n), percentages (%), median and interquartile range.

Results

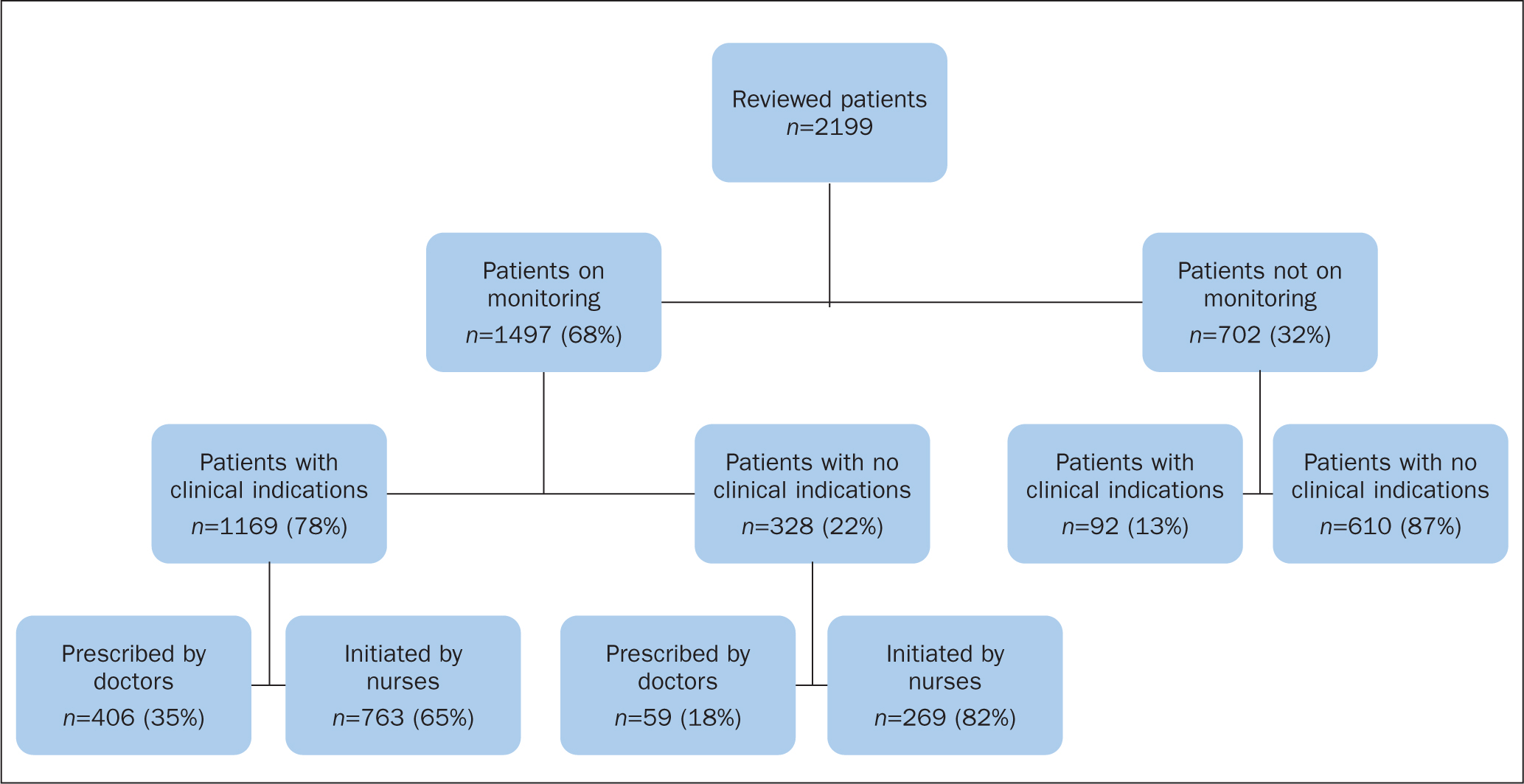

A total of 2199 patients from both the medical and surgical disciplines were included in this audit review (Figure 1). The patient characteristics are reported in Table 2. Of the reviewed patients, 53% (n=1169) were male, and the median age was 60 years (interquartile [IQR] range: 35–67 years). A total of 68% (n=1497) of the patients were on intake and output monitoring, of whom 707 (47%) were male, and the median age was 50 years (IQR range: 31–65 years). Among the patients who were receiving intake and output monitoring, this was clinically indicated in 78% of patients (n=1169) according to the recommended operational definitions, and 22% (n=328) had no clinical indications (NICE, 2017) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of reviewed patients, overall number of patients on fluid intake and output monitoring with and without clinical indications, and prescribed by doctors or initiated by nurses

Figure 1. Number of reviewed patients, overall number of patients on fluid intake and output monitoring with and without clinical indications, and prescribed by doctors or initiated by nurses

Table 2. Patient characteristics and fluid intake and output monitoring status

| Overall patients | Patients on monitoring | Monitored patients with clinical indications | Monitored patients with no clinical indications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | n=2199 | n=1497 | n=1169 | n=328 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 1169 (53) | 707 (47) | 572 (49) | 135 (41) |

| Female, n (%) | 1030 (47) | 790 (53) | 597 (51) | 193 (59) |

| Age (year), median (interquartile range) | 60 (35–67) | 50 (31–65) | 50 (31–65) | 44 (27–63) |

| Admitting disciplines | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Endocrinology | 110 (5) | 100 (91) | 68 (68) | 32 (32) |

| Infectious disease | 105 (4.8) | 98 (93) | 70 (71) | 28 (29) |

| Internal medicine | 100 (4.6) | 89 (89) | 78 (88) | 11 (12) |

| Renal medicine | 100 (4.6) | 88 (88) | 49 (56) | 39 (44) |

| General surgery | 100 (4.6) | 87 (87) | 87 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Neurosurgery | 100 (4.6) | 87 (87) | 79 (91) | 8 (9) |

| Orthopaedic surgery | 100 (4.6) | 86 (86) | 83 (97) | 3 (3) |

| Rheumatology and immunology | 100 (4.6) | 84 (84) | 56 (67) | 28 (33) |

| Psychiatry | 91 (4) | 83 (91) | 11 (13) | 72 (87) |

| Burns | 100 (4.6) | 83 (83) | 83 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Gynaecology | 100 (4.6) | 83 (83) | 75 (90) | 8 (10) |

| Medical oncology | 100 (4.6) | 81 (81) | 78 (96) | 3 (4) |

| Haematology | 100 (4.6) | 64 (64) | 51 (80) | 13 (20) |

| Neurology | 100 (4.6) | 63 (63) | 41 (65) | 22 (35) |

| Respiratory medicine | 100 (4.6) | 59 (59) | 48 (81) | 11 (19) |

| Plastic surgery | 100 (4.6) | 53 (53) | 51 (97) | 2 (4) |

| Dermatology | 57 (3) | 53 (93) | 21 (40) | 32 (60) |

| Urology | 100 (4.6) | 45 (45) | 43 (96) | 2 (4) |

| Hand surgery | 100 (4.6) | 36 (36) | 34 (94) | 2 (6) |

| Colorectal surgery | 100 (4.6) | 21 (21) | 20 (95) | 1 (5) |

| Geriatric medicine | 23 (1) | 21 (91) | 15 (71) | 6 (29) |

| Rehabilitation medicine | 13 (0.6) | 13 (100) | 10 (77) | 3 (23) |

| Gastroenterology and hepatology | 100 (4.6) | 12 (12) | 11 (92) | 1 (8) |

| Otolaryngology | 100 (4.6) | 8 (8) | 7 (88) | 1 (13) |

Of the monitored patients with clinical indications, 49% (n=572) were male, and the median age was 50 years (IQR range: 31-65 years). A total of 35% (n=406) were prescribed by the medical teams and 65% (n=763) initiated by nurses.

Among those who were monitored and had no clinical indications, 41% (n=135) were male, and the median age was 44 years (IQR range: 27-63 years). A total of 18% (n=59) were prescribed by doctors, while 82% (n=269) were initiated by nurses.

Among the patients who were not on intake and output monitoring (n=702), 13% (n=92) had clinical indications for monitoring.

Overall, documentation accuracy of the intake and output charts was 77%, with 23% of the charts inaccurately completed. Oral and intravenous fluid intake were both documented in 100% of cases, and with accurate output documentation in only 21% of cases. Among the inaccurate documentation of monitoring with no quantifiable amount, ‘void in toilet’ was the most often used inaccurate documentation, at 93.3%, followed by ‘wet incontinence knickers/pants’ with 4.6%, ‘BO (bowel open) x_times’ with 3.0%, and ‘vomit x_times’ with 0.1%.

Discussion

This review identified two main areas for improvement in the monitoring and documentation of fluid balance.

Inappropriate prescribing

First, fluid balance monitoring was not appropriately prescribed for some patients. Twenty-two per cent of the patients who had records of fluid balance charts had no clinical indications for fluid balance monitoring. Similarly, 13% of patients who were not placed on fluid balance monitoring did have clinical indications that required daily monitoring. This disparity suggests the need for clearer guidelines to aid the healthcare teams in assessing the need for fluid balance monitoring, consistent with previous literature findings (Gao et al, 2015). Previous reviews investigated the practice of fluid management and prescribing in adult acute care inpatients and reported the need for medical teams to improve the reviewing of intake and output charts and guidelines for fluid balance monitoring and documentation in clinical practice (Kamarudin et al, 2013; Gao et al, 2015). It is also included as one of the key recommendations in the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) for hospitals to have structured systems in place for accurate fluid balance monitoring in patients during hospitalisation, emphasising the importance of carrying out corrective actions if there are abnormalities (Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, 2018).

In other studies, the number of patients with monitoring orders from medical teams was at a relatively low rate (average 40%) among those patients receiving monitoring, indicating unclear practices in both medical and surgical hospital settings (Vincent and Mahendiran 2015; Nazli et al, 2016). There was a lack of awareness and knowledge of the clinical indications for fluid balance monitoring among healthcare staff, including both doctors and nurses (Gao et al, 2015; McCrory et al, 2017). Previous reviews indicated that the failure to regard fluid balance prescription and monitoring as vital elements of patient management contributed to increased inaccuracies of monitoring (Kamarudin et al, 2013; Gao et al, 2015). In the present study's hospital, only the order that ‘intravenous therapy will be discontinued’ is documented in the patients' electronic medication records. There are usually no written orders of discontinuation of fluid balance monitoring when it is no longer required, resulting in unnecessary continuation of monitoring and documenting for those patients. Future quality improvement efforts, with the collaboration of the doctors and nurses, could focus on designing a fluid balance monitoring algorithm. This algorithm should provide an accurate, consistent and quick assessment of patients' clinical indications to start and discontinue fluid balance monitoring.

Improving accuracy of documentation

The second area where improvement was needed was the accuracy of the hospital's fluid balance documentation, especially the output documentation. This result was similar to past reports from other acute care institutions where their average accuracy for fluid balance documentation was around 70% (Vincent and Mahendiran, 2015). Insufficient training and education is a significant contributor to inaccurate monitoring (Jeyapala, 2015). It seemed that nursing students, newly graduated staff, and even senior staff find it challenging to know how to accurately document fluid input and output, including what to document, what not to document and how to document appropriately. The abbreviations ‘PUIT’, which means ‘passing urine in toilet’ and ‘PU’, which means ‘passed urine’ were commonly reported in several studies (McLafferty et al, 2014; Jeyapala et al, 2015; McGloin, 2015). This indicated inaccurate recording of urine measurements as no quantifiable amount was recorded (Smith and Roberts, 2011). It is recommended that patients use bottles or bedpans with measurement markings to monitor their output, including nasogastric drainage, vomit, wound drains, rectal drainage, urine and stool in liquid form (McGloin, 2015). There is a need for further training and education of staff to improve understanding and knowledge of the accurate way to document this, as well as improving patient awareness of the importance of maintaining accurate intake and output monitoring. Identifying factors that contribute to the inaccuracy of fluid balance documentation is essential to improve current practice. Future work should focus on qualitative interviews with health professionals to elucidate what enables or challenges accurate documentation.

It has been widely reported that inaccurate fluid balance monitoring and poor documentation can compromise patient safety and result in poor clinical outcomes in patients (Grams et al, 2011; NICE, 2017). Increasing the recognition of disparities in current monitoring and documentation practice can help establish the need for improved practices and guidelines.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that this study may have some limitations. First, power analysis was not done to calculate the sample size. This study was conducted to generate a snapshot to evaluate current care and to identify existing shortfalls in care, with the aim of improving the quality of the hospital's patient care. Future statistician calculation of sample size will be vital to improve the generalisability of the audit findings. Second, as this was a retrospective review, we were unable to ensure the completeness of the patients' records. This audit review also did not review the accuracy of fluid administration, nor did it assess for the intake and output chart documentation completeness. In addition, other reasons for monitoring without clinical indication and rationales for lack of monitoring in those with clinical indications were not reviewed in this study. Lastly, our findings were limited to one hospital's practice and may not be generalised to other hospitals with different practices and guidelines.

Implications for practice

It is essential that hospital staff recognise the need to improve the current practice of ordering, monitoring and documenting fluid input and output in patients. A taskforce comprising both the medical doctors and nurses needs to be established to work on the design of an intake and output monitoring algorithm that could aid in the improvement of fluid balance monitoring that is clinically indicated and accurate for patients. If the algorithm was widely publicised in the hospital, this would help nurses to identify those patients with high-risk factors who require strict monitoring.

Regular in-service training sessions on the importance and clinical indications of intake and output monitoring are essential to update the knowledge of healthcare staff. In addition, regular auditing enables wards to identify areas that require improvement. Auditing of new practices can also allow evaluation and review of care and practices, which aids in achieving and sustaining change (Jeyapala et al, 2015).

Conclusion

This study found that the appropriateness and accuracy of the fluid balance monitoring and documentation in one acute care hospital was not ideal. The current disparities in practice include prescribing fluid balance monitoring for patients without a clinical indication and documenting incomplete or poor quality information in patients' intake and output charts. Future quality improvement and research work is needed to address these gaps to enable an efficient work process and improve patient safety and outcomes.

KEY POINTS

- Accurate monitoring and documentation of fluid input and output is vital in certain patient groups, such as those with heart failure and kidney problems

- A lack of or inconsistent documentation has been reported in the literature

- This study found inconsistent documentation, patients requiring monitoring not receiving it and those not requiring monitoring receiving it

- The authors recommend the use of an algorithm for doctors and nurses to use to indicate which patients require monitoring of fluid intake and output

CPD reflective questions

- Are patients' fluid intake and output routinely monitored in your clinical area or is such monitoring for specific patients only?

- What does your clinical area do to ensure accurate fluid documentation?

- What measures could you take to improve fluid documentation in your area?